‘Leave the ship where it is’: why nobody wanted to Raise the Titanic

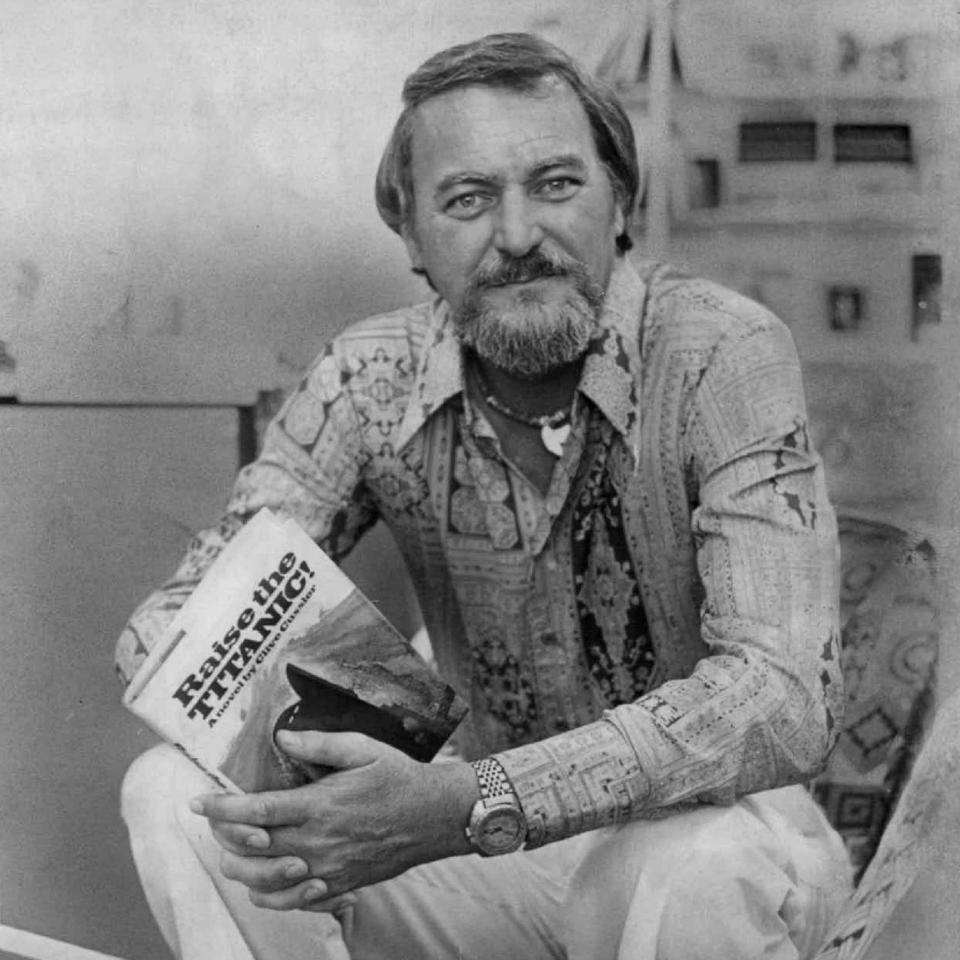

As waves gently buffeted St Ives’s 18th-century Smeatons Pier, Richard Jordan fixed his bearded jaw at a heroic angle and unleashed a dazzling matinée-idol smile.

“I really hate punk clothing and artificial-looking hair,” the star of Logan’s Run and Klute told an admiring gathering of what the Raise the Titanic official press kit described as “a half dozen British college-age girls”.

“I saw a couple of girls recently in London who had hair just sticking up straight. I don’t know how they did it. And it was dyed blonde with green streaks!”

Oozing Hollywood charm, Jordan (42) had the audience at St Ives enraptured. Alas, his magnetism would mysteriously abandon him later that day when it was time for his big scene with Alec Guinness.

Guinness played a survivor of the Titanic who had insider-information that was of interest to Jordan’s swashbuckling anti-hero, Dirk Pitt. Raise the Titanic was the grand old thesp’s first blockbuster since Star Wars in 1977 (discounting a cameo in sequel The Empire Strikes Back). He had famously loathed that film. He probably wasn’t all that much keener on Raise the Titanic, which, on its release on August 1 1980, would go down… well, like an ocean liner that had recently struck an iceberg.

He didn’t grumble about it, however, nearly as much as he had about George Lucas’s space opera. That was possibly because Raise the Titanic paid him £45,000 – the equivalent of nearly £200,000 today – for just four days’ work.

The St Ives scene pops up around a third of the way into Jerry Jameson’s adaptation of the Clive Cussler bestseller. Pitt, a bad-boy explorer of shipwrecks, is in Cornwall to pick the brains of Guinness’s John Bigalow, one of the last living survivors of the Titanic.

He does so in the hope of discovering the whereabouts of a stash of “byzantium”, a rare (and entirely fictional) mineral with uranium-like properties that has gone down with the liner. Possession of byzantium could give the United States – or the Soviet Union – a winning advantage in the Cold War. And so the race is on to… Raise the Titanic!

The exclamation mark was courtesy of Cussler, who had insisted it be appended to the title of his 1976 bestseller. That it was removed from Jameson’s big-screen version tells us everything about why the novel worked and the film didn’t. The former was pulpy, throwaway fun; the latter was portentous, slow-moving – and horrendously expensive.

Raise the Titanic is generally forgotten today. Yet, with a budget of $40 million and box-office takings of just $7 million, it cast a shadow over Hollywood for decades. It could have been the Heaven’s Gate of its generation, had the actual Heaven’s Gate not beaten it to the punch.

It certainly fouled the waters for blockbusters about unsinkable liners crashing into icebergs. When the vultures circled James Cameron’s “troubled” Titanic in the mid-1990s, one of the reasons it was assumed the movie would flop was because of Raise the Titanic. If pulp maestro Clive Cussler and old-time studio boss Lew Grade couldn’t make a film about the Titanic float, what chance had sci-fi specialist Cameron?

Grade, the doyen of British cinema at the time, had gulped down Cussler’s novel in four hours. And then flown straight to New York, determined to seal a deal with the author at any price.

Cussler was still a young writer, but was already developing control-freak tendencies. He agreed to sell the rights to Grade on the proviso that he have a cameo and a line of dialogue. Grade cast Cussler as a reporter at a press conference and then removed him from the final cut.

The author also had strong opinions about the best actor to portray the mercurial Pitt. He pushed for Steve McQueen, who wasn’t interested. Grade then approached Elliot Gould. He was even less enthusiastic. “I don’t want to raise the Titanic,” he said. “Let the Titanic stay where it is.”

To Cussler’s disgruntlement, the part went to C-lister Jordan. He was a respected name on Broadway, but as a movie star his wattage would have struggled to light a third-class cabin. Adding to the insult, Cussler was outraged to discover that Oscar winner Jason Robards, playing Admiral Sandecker, head of his fictional NUMA sea-exploration agency, hadn’t even read his book.

“Well, I guess we’ll see Jason Robards rather than Admiral Sandecker,” Cussler thundered, before stomping away. Robards didn’t take the outburst to heart. Asked why he had signed up to what was clearly a doomed project, he replied: “Money, m’dear. Money.”

Robards added that he and the rest of the cast were “all incidental to the hardware and the special effects on this one”. And that is ultimately where Raise the Titanic was sunk.

Grade, a former professional dancer born to a Jewish family in Ukraine, was a self-made studio kingpin. His successes included The Boys from Brazil, The Long Good Friday and the Pink Panther and Muppet movies.

With Raise the Titanic, he had set out to make a grand disaster picture in the tradition of The Towering Inferno and Earthquake. To that end, he hired John Richardson, the special-effects supervisor from Moonraker, to create a 55-foot-long, 10-tonne replica of the Titanic.

A Titanic expert, Ken Marschall, was brought on board, too, to ensure the accuracy of the model. But the sheer scale of the endeavour soon began to pose a challenge. In addition to the $5 million lavished on the ship, the team had to spend $3.3 million on a 350-foot-long, 35-foot-deep tank to house it at Mediterranean Film Studios in Malta.

This put the total budget for the Titanic and its watery grave at $8.3 million – more than the $7 million it had cost to build the original RMS Titanic at 1911 prices. Next, the team had to source a real ship for the scenes in which Pitt and his men board the ship after resurrecting it using an unlikely combination of explosives, compressed air tanks and buoyancy aids.

Months of searching finally led Richardson and Marschall to a shipyard outside Athens and a mouldering hulk, the SS Athinai. But there were major structural difference between it and the Titanic. And so the FX crew had to go back to their $5 million model and make it less accurate, so as not to clash with their newly acquired rust-bucket (which cost $250,000 to “restore”).

Even away from the water, the journey from the page to the screen was proving problematic. Having paid Cussler $450,000 for the rights, Grade had hired Stanley Kramer to direct. Kramer was a diverse filmmaker, with such accomplishments to his name as Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner?, High Noon, Judgment at Nuremberg and It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

Kramer, however, knew a disaster when he saw one, and he realised that Grade’s projected budget of $9 million was hopelessly unrealistic. He was concerned, moreover, about the underwhelming cast and the technical challenges posed by the subject matter. Did he want to spend two years of his life mucking around with model ships and water tanks?

“The factors were casting and the number of miniatures we planned to use,” he said. “You might say one of the possibilities as to why I left was that I felt things might have cost more. It’s always a little sad to see it happen this way. Raise the Titanic was a big challenge – all the excitement of special effects, underwater filming.”

Cussler was dubious, too, especially as the script went through a rumoured 10 rewrites. “The film is supposed to cost between $12 and $15 million, which is difficult for me to believe,” he confessed to the Associated Press. “The special effects will be enormous, especially in two scenes: when the ship comes up to the surface, and when it is towed into New York harbour.”

Grade, though, was thrilled with what he was seeing. He believed, in particular, that the special effects were state-of-the-art. When the Titanic came crashing up from the surface of its Maltese water tank, he felt as though the real ship were being conjured forth from the abyss.

“When John Barry was adding the score, he had an 87-piece orchestra,” Grade enthused. “They were in the middle of scoring that part when it came time for their mandatory 10-minute break. But the musicians didn’t want to leave. They wanted to see the sequence again, and then they all applauded. For a group of blasé musicians, that is practically unheard of.”

His optimism will have been fuelled by progress in the real-life hunt for the Titanic and the publicity it generated. In July 1980 – weeks before the film’s release – Texas oilman Jack Grimm set off from Florida in research vessel H.J.W. Fay. He had previously sponsored expeditions to track down Noah’s Ark, the Loch Ness Monster, Bigfoot and a giant hole supposedly located at the North Pole.

Now he had the Titanic in his sights. His research ship was packed with experts from Columbia University and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. He also had on board a monkey named Titan, supposedly trained to find the Titanic on a map.

The scientists weren’t best pleased to be sharing the spotlight with Titan and told Grimm, “it’s either us or the monkey”. Even with the monkey out of the picture, their search proved fruitless. However, the coverage was a welcome boost for Grade. (The Titanic would finally be found on September 2 1985, entirely without the aid of monkeys.)

Grade’s enthusiasm for Raise the Titanic and its special effects was not shared by critics. “The glistening, quivering air bubbles that burst out of the ship should be readily familiar to anyone who’s ever broken a thermometer,” lamented Janet Maslin in the New York Times.

“They look just like globs of mercury, and there’s no mistaking the miniature Titanic for anything truly ship-sized. Nor will anyone imagine, in the process shots near the film’s ending, that a real, rusted ocean liner has actually made its appearance in New York harbour.”

As a grand spectacle, Raise the Titanic certainly ticked the boxes. But it was also as creaking and slow-moving as a battleship attempting a U-turn. And by 1980, a more nimble genre of blockbuster was taking over. This was exemplified by The Empire Strikes Back, which had a budget of just $33 million – from which it earned half a billion.

Grade felt that the huge budget had made Raise the Titanic an easy target. “They like to criticise pictures that cost a lot,” he would say. “Just like women like to criticise women who wear expensive jewels and expensive clothes.”

One factor in its downfall, he would tell friends, was a rival movie, SOS Titanic, made for TV but given a cinema release in September 1979. The theatrical distribution was handled by EMI Films, of which Grade’s brother, Lord Delfont, was chairman. Grade had been undone by his own flesh and blood.

Cussler, who passed away this February at the age of 88, was furious about Raise the Titanic. He refused for years to allow Hollywood to adapt his books. He finally relented in 2006 when Matthew McConaughey portrayed Pitt in Sahara – but that movie was as epic a disaster as Raise the Titanic had been. Cussler duly sued the producers for failing to give him the control over the script that he claimed he had been promised.

The true mystery, arguably, was why Raise the Titanic was so quickly forgotten. After all, it marked the beginning of the end of Grade’s ITC movie empire, with two further flops, Saturn 3 (1980) and The Legend of the Lone Ranger (1981), confirming his decline. It deserves, at the least, a place in cinema’s hall of infamy.

One theory is that, as already mentioned above, its failure was eclipsed by Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, which came out in November 1980. The two films had similar budgets – $44 million for Heaven’s Gate , $40 million for Raise the Titanic. And both performed meagrely at the box-office.

The distinction, of course, is that Heaven’s Gate was a prestige project with a big-name cast and an Oscar-feted director. Whereas Raise the Titanic was merely a disaster movie slipping silently beneath the waves. Even as a Hollywood cautionary tale, it didn’t make a splash.