In Kingdom of Silence, Jamal Khashoggi's Life Shows Us We Will All Someday Have to Choose a Side

One of the first rules of being a Serious Person is that nothing in this world is black and white. Everything, the wise man says, is in shades of gray. The grownups know that in the real world, lofty principle runs aground on the rocks of power and necessity. But then there is the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi, and there's Kingdom of Silence, the maddening new documentary on Khashoggi's life and death, which dares ask whether some things in this world really are gray at all. What if some of the stories we tell ourselves about nuance and compromise and realpolitik are little more than lies to justify the choices we make?

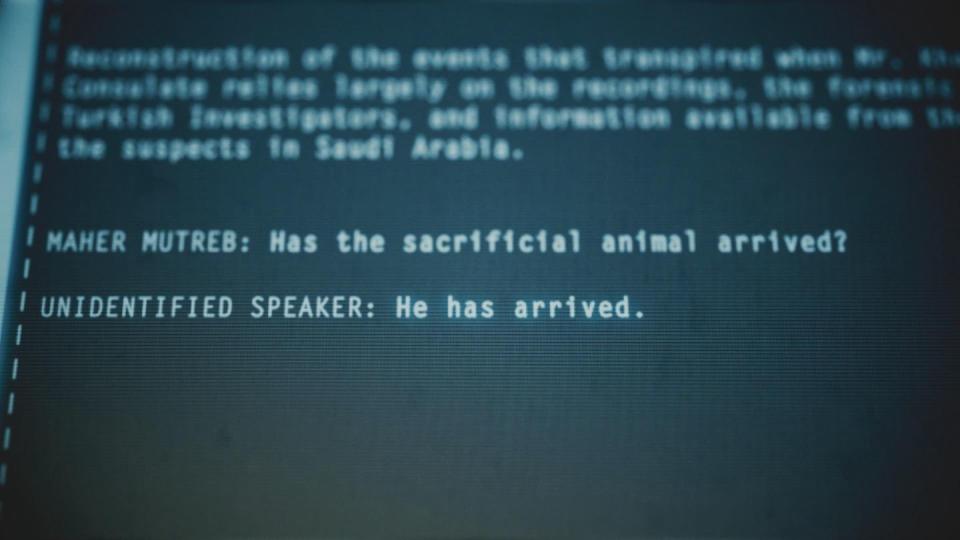

Although there is often a lot of gray. At the heart of the film, a Showtime production directed by Rick Rowley and executive produced by Lawrence Wright and Alex Gibney, there is the story of Khashoggi himself and his attempts to run the gauntlet of life as an intellectual in Saudi Arabia. He first makes his name as a journalist aligned with the Saudi royal family, embedded in Afghanistan with the Mujahideen and its young and charismatic leader, Osama bin Laden. The story ends with Khashoggi in the role of dissident expatriate, speaking truth to the new powers that be in the nation of his birth—until one day he was dead, murdered and dismembered by Saudi intelligence agents in the Kingdom’s consulate in Istanbul. Along the way, Khashoggi broke with bin Laden after the 9/11 attacks, became an outspoken proponent of the United States invasion of Iraq, and tiptoed around the great potential and greater disappointment of the Arab Spring.

By his later life, Khashoggi became convinced that there was "a third way" between the revolutions of the Spring, which promised freedom of expression and self-determination for the people of the Arab world, and the autocratic fist of the ruling regimes that dominate the region. When the revolutions faltered—helped along, the film shows us, by the Saudi royal family's meddling in Egypt—Khashoggi wanted to find other ways to carve out more space for individual self-expression. Lawrence Wright, his personal friend and also a voice in the film, explained this when we spoke over the phone ahead of the film’s Friday premiere.

"If you live in the neighborhood that Saudi Arabia does, and you look around at the revolutions that have taken place in Iraq, in Sudan, in Egypt, in Iran, they don't turn out well," said Wright, a staff writer at The New Yorker who won the Pulitzer Prize for his book on Al-Qaeda, The Looming Tower. "Saudi Arabia has this inborn fear of dissolving into tribal warfare. So this anxiety that is a part of Saudi culture just keeps real change from happening, because of the threat that is always made that it'll turn into just blood in the streets. And it might. But that's why Jamal and other reformers in the Kingdom have always advocated peaceful change—that you don't hear very much about eliminating the royal family—if what you're trying to do is find more space for other individual Saudis to express themselves."

Khashoggi was in a particular position to pursue this because he occupied a new and unusual station in Saudi life. He was neither royal nor a commoner. He was something in between, much like bin Laden, whom Wright describes as the first Saudi celebrity—a category that, until his rise, did not exist. They both owed their status to their time in Afghanistan in the 1980s, when bin Laden led the Mujahideen’s jihad against the Soviet occupation—with American support—and Khashoggi helped, through his writing, to construct bin Laden’s image as a mythic hero of Arab liberation. While Wright contends bin Laden’s reputation wasn’t quite earned—that his group played little real role in winning the war against the Soviets—the consequences were very real for both bin Laden and his chronicler.

“That's just very unusual in Saudi Arabia,” Wright told me of Khashoggi, “that he was his own man.” That was ultimately what put him in such grave danger amid the rise of King Salman and his son, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, whose first act was to close down the brand new independent news network, Al-Arab, that Khashoggi was leading. “He had a voice, and it was becoming stronger because of the platform that he was standing on, the Washington Post,” Wright added, referring to a few years later. “You know, there's really only one voice that is allowed in Saudi Arabia—well, I should say two. There's the royal family, and there's the clerics.”

In the film, one speaker calls the Post, “the voice of empire,” a testament to the risk Khashoggi had taken on by the time he’d fled the Kingdom for Washington, D.C. and started writing his columns. Kingdom of Silence delves deeply into the U.S.-Saudi relationship, which Wright told me began not with greed or geopolitics or exploitation, but philanthropy. An American who went to a desperately poor Saudi Arabia in the 1930s to try to get the country set up with toilets asked the king what else he could do to help. The king said they needed water—could you send a geologist? One soon arrived. “He told the king, ‘Well, I've got good news and bad news,’” Wright narrated. “No water, but you've got oil.” From then, particularly when oil rose to be a critical geopolitical commodity with World War II, the Saudi relationship became a top priority for the U.S., one which only grew more essential in the eyes of the American leadership when the Shah of Iran fell in the 1970s.

There’s a lot of talk these days about the “transactional” nature of Donald Trump’s politics, but he is, as usual, merely the most grotesque expression of a longstanding principle the United States has held in its posture towards Saudi Arabia. In the film, a longtime U.S. ambassador to the Kingdom, David Rundell, features prominently as the self-styled voice of pragmatic realism. He characterized the Saudi royal family’s meddling in Egypt, which ultimately toppled a democratically elected regime and installed a military dictator, as necessary for the stability of the region. There was no discussion of what the Egyptian people might have wanted. He dismissed Khashoggi’s murder as “the death of one person,” a trivial event when compared to the overall U.S.-Saudi relationship. Trump dismissed the assassination in hideous terms, immediately citing how much money the Saudis pump into the coffers of American defense contractors, but Rundell’s calculus was largely the same. That Khashoggi’s murder was meant to send a message to others who might speak out in favor of human rights, and placed reporters and journalists in the region in even greater peril, did not factor into the equation at all. It was the cost of doing business with a monstrous friend.

I asked Wright whether this kind of functionally amoral attitude would become necessary—inevitable, even—when, as a diplomat, you’re asked to operate for so long within a setup where America’s professed values are continually ground up and sacrificed for some purportedly larger goal. Compromises, trade-offs, middle roads.

“There's what's called a realist school in diplomacy, and I think Rundell is from that. It's the same line of thinking that has accommodated a lot of Europeans to Putin. He kills Russians on European soil. And yet there's this pipeline to consider. So are we willing to trade off a few assassinations in order to keep our economy moving? Those kinds of calculations are always made in the world of geopolitics. That's one of the reasons that people like that remain in power, because there's not enough impetus to confront them at the political level. And that's why documents such as our film are required, to rally the moral courage to actually face up to these tyrants.”

The American transactionalism is on full display throughout the film. We provided support to the Mujahideen in Afghanistan as a proxy war against the Soviets. There is frankly mind-bending footage of Ronald Reagan hosting an Afghan delegation at the White House, saluting them as “a nation of heroes.” Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, openly said that we’d sought to give the Soviets “their own Vietnam”—and considered it a success. “To his dying day, Brzezinski thought it was worth it,” Wright told me, “despite the fact that 9/11 was a consequence of it.” We hardly knew it at the time, but the United States was providing funding and support that would help spread radical Islam. To illustrate how little the two parties understood about each other up to that point, Wright told me that during their visit, one of the Afghan resistance leaders tried to convert Reagan to Islam.

When the Soviets pulled out of Afghanistan, bin Laden was by then a kind of warlord, percolating in his own mystique and eager to keep the show going. Khashoggi was actually dispatched by the royal family to bring bin Laden back to the Kingdom, where he could renounce his radicalism for a sweet payday. Khashoggi failed, bin Laden went on to establish Al-Qaeda, their relationship fractured, and by 9/11 it was destroyed completely. Of course, the royal family also provided funding to Al-Qaed, and the film reports King Salman, now the country’s figurehead, served in the ‘90s as the chief bundler for royal money headed to fund radical terror. Few people knew more about this dynamic than Khashoggi, who was beginning, at the time of his murder, to meet with representatives from 9/11 victims’ families who have leveled a lawsuit accusing the Saudi government of complicity in the attacks. The film argues it was a factor in the decision from MBS—King Salman’s son—to assassinate him.

Khashoggi seemed to live many lives—including, by the end, two marriages at once—but the constant was this quest to carve out some space for free expression in his homeland. He ultimately had to flee it—and leave his first wife and family there—to keep hold of his own freedom. He saw Mohammed bin Salman for what he was well before the Western press and business elite, who showered the crown prince with praise for what appeared, from the outside, to be serious reforms. Wright admits he was one of those believers.

“The last time I saw Jamal was March two years ago. I arranged for him to come down to Austin where I was. We had a panel together at the university, and I was honestly puzzled by Jamal's opposition to MBS. When I left Saudi Arabia, I had all these young reporters I was teaching at this newspaper in Jeddah. And there were two women reporters, and I broke precedent by actually meeting with them, insisting that they be a part of the weekly meetings we had. So when I said goodbye, I gave a gift to my reporters, and to the women I gave keychains, UT Longhorn keychains, for when they could finally drive.

“I thought, this is real progress, and that's what Jamal had been advocating for, for years. So what's the problem? And he said, ‘It's never been more difficult to speak.’ And his own experience was he was being silenced, not allowed to publish. Finally, he wasn't allowed to tweet. And he was getting lots of death threats. So the paradox of the rule of MBS is that the people who advocated reform, like the women who advocated for driving, are in prison. Their crime—although they haven't been charged—is that they wanted to drive, and they said it aloud. MBS understood the longing of so many young people for some kind of freedom, and driving is a great form of freedom. But he also understood that there can only be one reformer in the kingdom, and anyone else who tries to speak out is silenced or imprisoned or, in the case of Jamal, murdered.”

The space for speaking freely in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has nearly been erased entirely now. The film traces the efforts of an MBS henchman to crack down on the press and social media. Even rival factions of the royal family have been bludgeoned into submission, most prominently with the move to turn the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton into a gilded prison. Khashoggi escaped just in time, having seen the writing on the wall, and having come to the conclusion—particularly after his independent news station was swiftly shuttered—that his “third way” could not be found. There would be no compromise or negotiation with this regime, which had taken a significant lurch towards autocracy even compared to previous regimes. In the film, Wright says that eventually the time came for Jamal Khashoggi to depart the gray area, with all its contradictions.

“America and the Kingdom have a toxic relationship, and it poisons not only our own societies, but it’s spread all over the world. The chaos, the wars, America’s had a big hand in that. And Jamal’s been in the middle of that from his earliest days. He embodied, in some ways, that relationship. But this contradiction became so obvious, you had to choose. Which side are you on?”

If Jamal Khashoggi tried to carve out some space for those in the land he loved to speak freely, the space in other nations across the world is shrinking, not growing. The conundrum of authoritarianism is that it creeps in, seeping through the cracks of flawed democracy, metastasizing in the gray areas of doubletalk and innuendo and propaganda. But the force itself is not gray. It is black as night, and it really does force us all, eventually, onto one side or the other. The time will come for every one of us to choose. The questions of whether the light can prevail, and whether those who have pledged allegiance to it can summon the strength and the clarity to face the darkness head on, will come to define our time.

You Might Also Like