Kansai Yamamoto Designed David Bowie’s Costumes—and Was a Legendary Designer in His Own Right

It was often said, after David Bowie’s death in 2016, that the legendary musician worked like fashion itself: With each album, he was also creating a new look, conjuring a new mood, in the ceaseless quest for constant reinvention and radical self-expression.

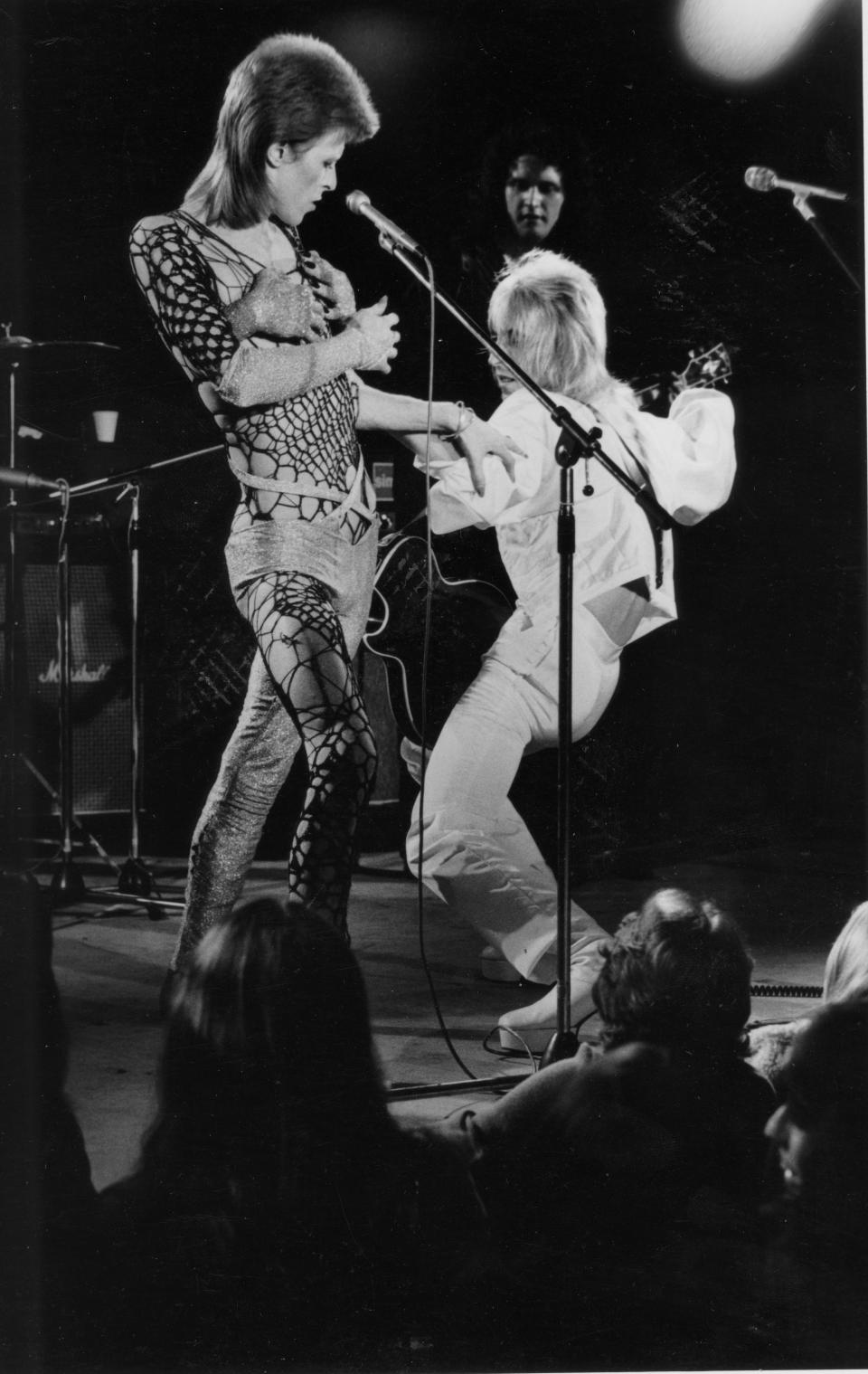

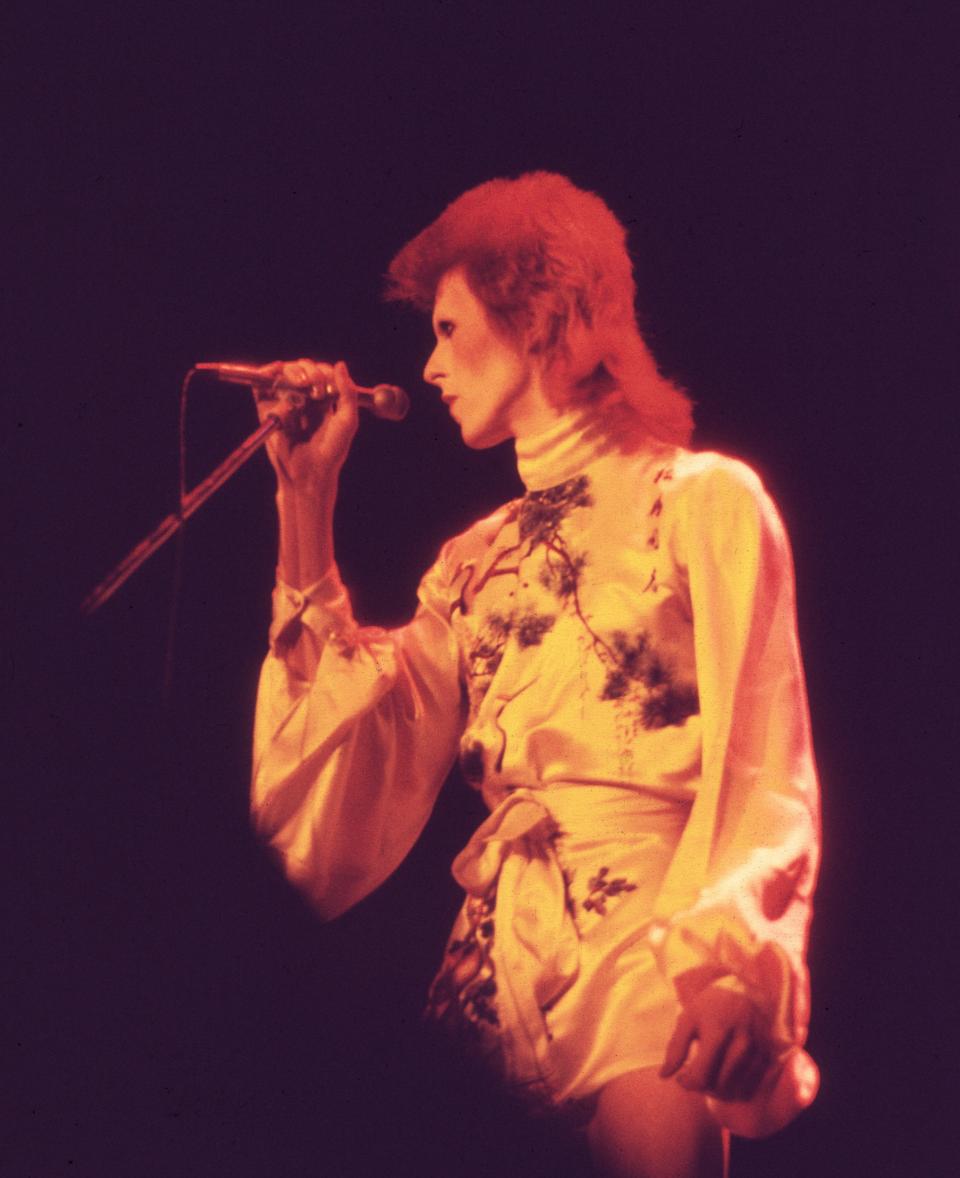

But for all his changeling qualities, to many people Bowie was always the man in the Kansai Yamamoto suits. Ask the average person to close their eyes and picture Bowie, and there he is in the splashy, exotic, and sexually charged creations worn onstage in the early 1970s as Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane.

Yamamoto, who died earlier this month of leukemia, leaves a legacy as one of the 20th century’s most exuberant fashion voices, not to mention one half of perhaps the greatest synergistic relationship between musician and designer in history. Only Nudie Cohn and Elvis, Madonna and Jean-Paul Gaultier, and Lil Kim and anyone who dared come close. (Unsurprisingly, Bowie was an avowed fan of Little Richard, who also crafted a distinctive visual appearance that was inseparable from the music.) When Bowie wore Yamamoto’s designs, the designer told Dazed in 2016, “some sort of chemical reaction took place: My clothes became part of David, his songs and his music. They became part of the message he delivered to the world.” The otherworldly style of the clothes made by Yamamoto (and Bowie’s other fashion collaborator from that era, Freddie Burretti), fed the music and vice versa. Together they helped perfect that other great Bowie invention: the stage persona. Ziggy Stardust became as real as Bowie himself.

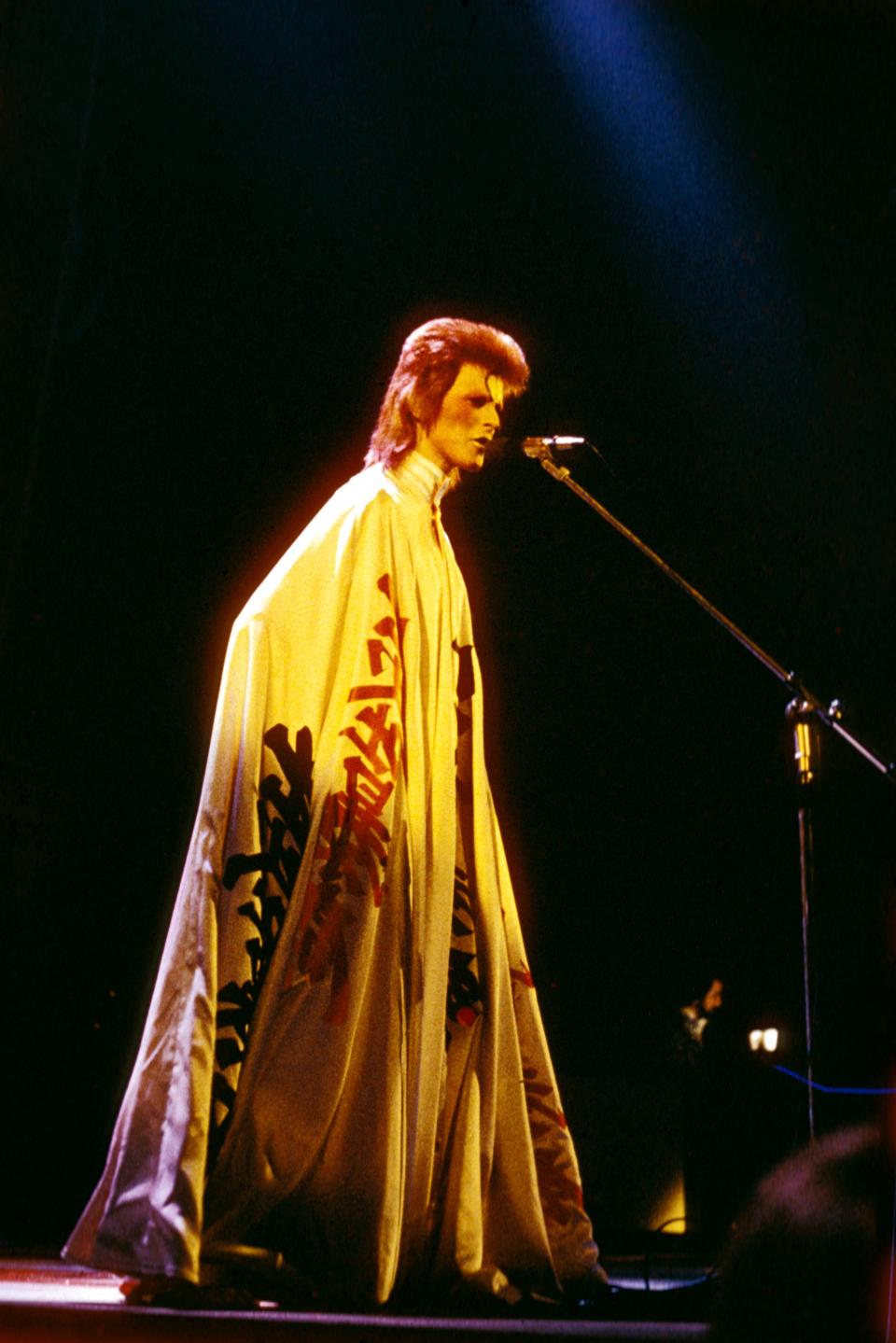

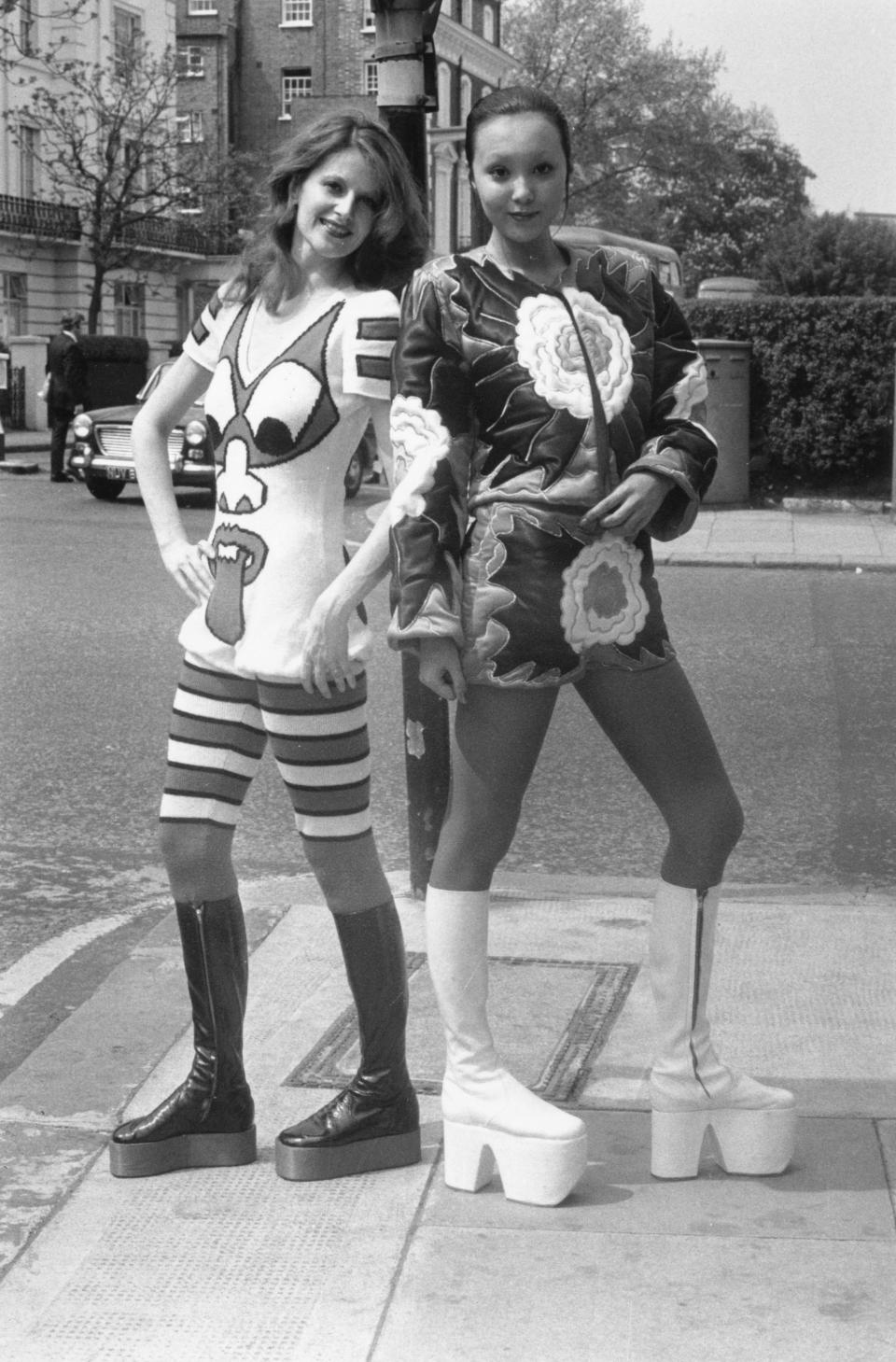

The formal innovation of Yamamoto’s work is still evident from images dating back to his London Fashion Week debut in 1971. His sassy knit playsuits, which revealed legs, chests, and thighs, must have been shocking to a country in which knitwear is something of a national obsession. Taking inspiration from the Japanese concept of basara, a style of flamboyance and extravagance, Yamamoto’s silk capes and separates were printed with Ukiyo-e paintings—depicting kabuki actors with their faces wrenched in high drama—at huge, gorgeous angles, and he cinched sleeves and waists with lengthy leather tube belts. Even today, when designers like Undercover’s Jun Takahashi have pushed these large-scale printing techniques into the 21st century, and Doublet designer Masayuki Ino is making hilariously inventive knitwear, the vintage goods look wild.

Japanese fashion has long been the toast of fashion’s avant-garde, but remember that the great debut of Japanese fashion in Paris—the arrival of Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto, and Rei Kawakubo—was nearly a decade away, and Yamamoto’s designs were intended for women, which made Bowie’s adoption of them even more shocking. In the early ’70s, London was still bopping along in the miniskirts of Mod innovator Mary Quant, and the bohemian glitz represented by the store Biba. In Paris, the most exotic thing going was the designer Yves Saint Laurent interpreting styles from Russia, the Middle East, and Asia—mostly places he’d never been. To see a Japanese designer implanting Japanese culture on European runways was revolutionary.

Even outside of his reputation as a cultural collider, though, Yamamoto wrote a significant chapter of 20th-century fashion. What Bowie was after with his legendary Stardust invention was an alien figure, something utterly unfamiliar, though undeniably beautiful and therefore slightly disturbing. The most progressive designers of the day—André Courrèges, Pierre Cardin, and Quant—were designing in a Mod style that foretold of a streamlined, cool, and possibly emotionless future. Yamamoto’s designs pointed to another world—“half out of sci-fi rock and half out of Japanese theater,” Bowie once said—that was expressionist and organic. Look at the way he handled vinyl, which was also a popular material for his Mod peers, in that famous Yamamoto-Bowie striped jumpsuit: Rather than rigid and machine-made, it looks light and even botanical, like someone sliced open a mysterious plant that landed with a thud from outer space.

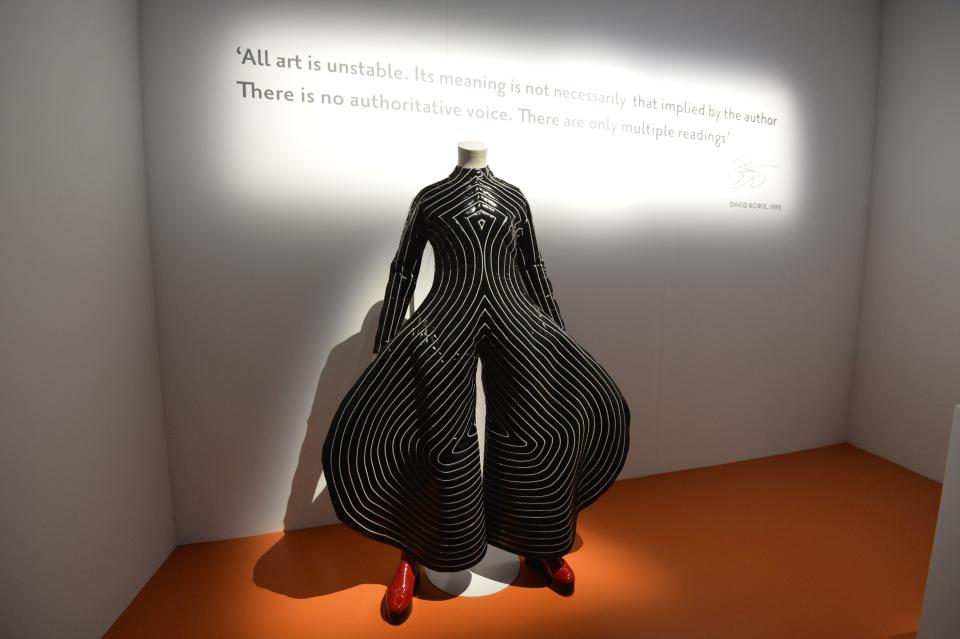

Yamamoto moved his shows to Paris in 1975, and continued to produce highly influential work during the ’80s, presaging the explosion of color and shape of Christian Lacroix and even the humorous reappropriations of Martin Margiela. (See the hands jumpsuit he designed for Bowie in 1973, which is now in the collection of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum and toys with a concept Margiela would take on with his glove top in 2001.) He showed his final collection in 1992, but unlike many of the less heralded designers who drove fashion forward during that time, he was duly celebrated after retiring, with the Philadelphia Museum of Art staging an exhibition of his work in 2009. The Yamamoto legend was further burnished with David Bowie Is, an exhibition of Bowie’s costumes first staged at the V&A in 2013—becoming the museum’s most-visited show of all time—which then traveled around the world and eventually landed at the Brooklyn Museum of Art to much fanfare in 2018.

Yamamoto also remained a constant inspiration to fashion designers: Louis Vuitton creative director Nicolas Ghesquière collaborated with him on his 2018 resort collection in Japan, putting Yamamoto’s Ukiyo-e figures on sequin tunics and handbags. Just this past January, Rick Owens quoted extensively from the Yamamoto oeuvre with one-legged and -armed jumpsuits modeled by Owens muse Tyrone Dylan Susman, one of the few men alive with the strange serpentine grace required to carry off a Ziggy-era Bowie tribute look. As the fashion cycle rolls on, one can only expect to see more Yamamoto tributes to pop up—all big stuff for, as Bowie sang in the titular “Ziggy Stardust” theme in a nod to his far-out fashion conspirator, “some cat from Japan.”

Originally Appeared on GQ