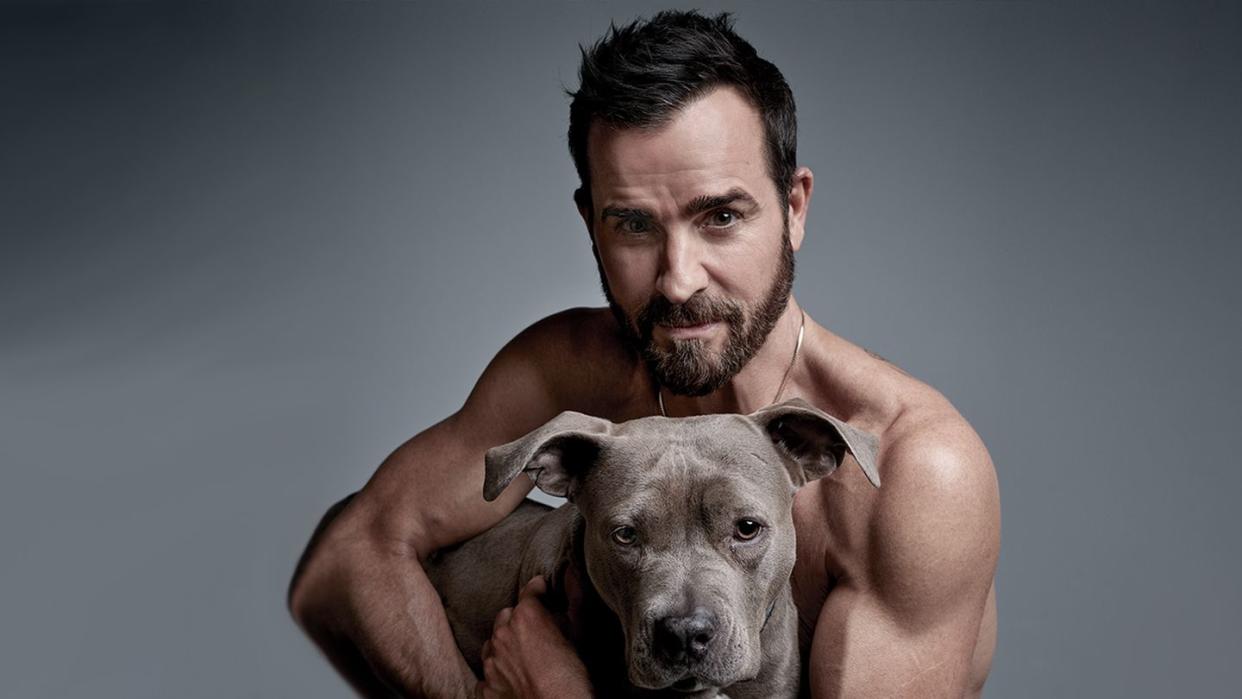

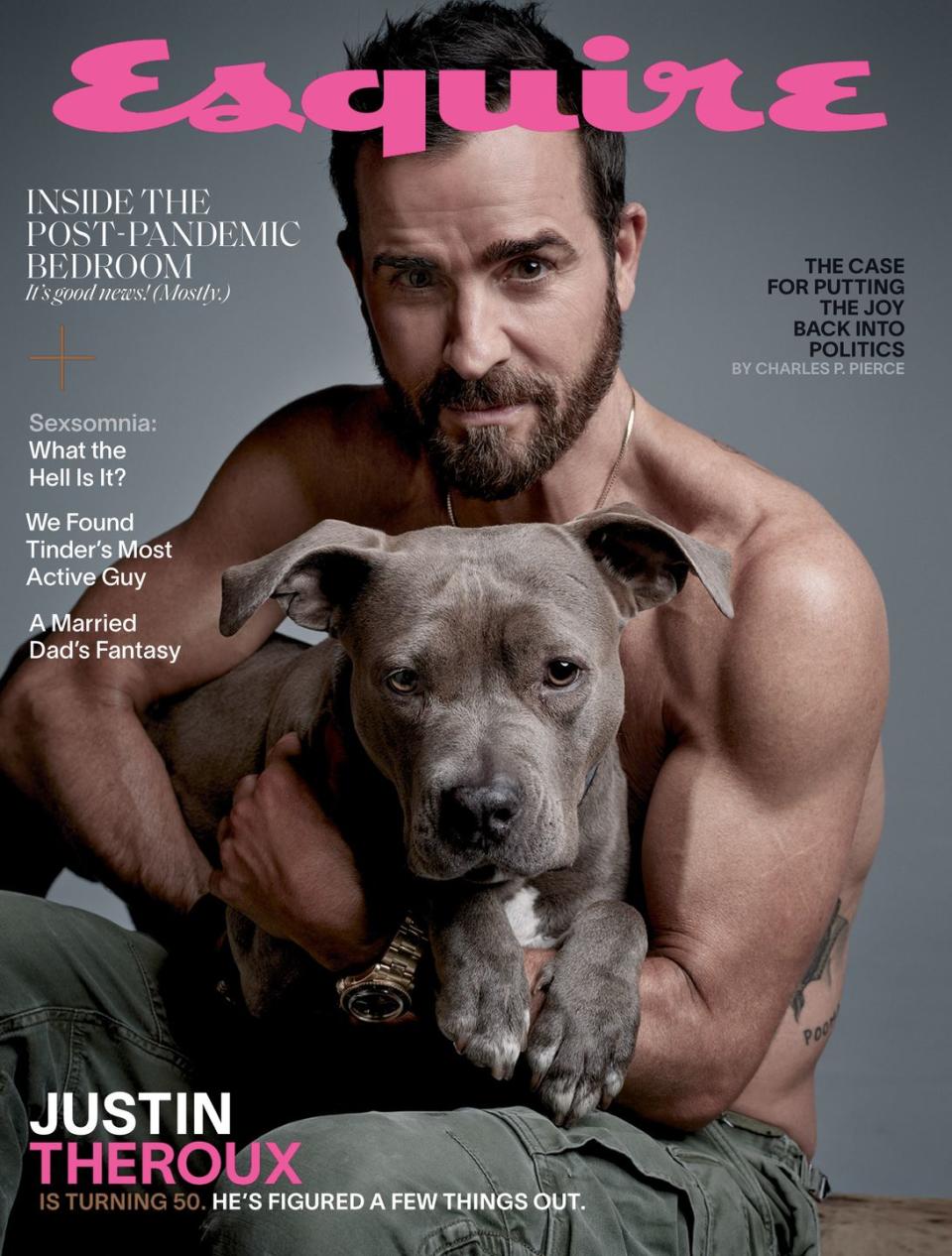

Justin Theroux Is Turning 50. He's Figured a Few Things Out.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Justin Theroux is ensconced in his Greenwich Village duplex. It’s the middle of February, “the shortest and the cruelest” of months, he says. We’re talking over Zoom. He’s wearing a black T-shirt over his non–dad bod, a black beanie, and, despite the waning daylight, tinted aviators. A russet beard covers his unfrivolous jaw. Behind him, there’s a glass case displaying wax molds of syphilitic mouths. He takes frequent drags from a Juul to supplement a steady supply of Nicorette; he quit vaping when the pandemic began and only recently resumed. “I reserve it for the evening hours,” he says, as if voicing an infomercial. It’s 3:30 p.m., close enough. He holds up a piece of gum. “Whereas the minute I open my eyes, I put this in.”

Listen, it’s been a stressful year.

In the lead-up to Covid-19, he was in Mexico, filming his latest project, Apple TV+’s The Mosquito Coast. When production halted in March 2020, Theroux returned to New York City and began stockpiling for his pod of one. (Two, if you count Kuma, his pit bull terrier.) He bought bone broth by the bucket; he hoarded garlic, ginger, and, for some reason, Parmesan cheese. “Perhaps I was being paranoid,” he says. Like everyone else, he couldn’t find toilet paper, but unlike the rest of us, he didn’t need it. “I have a Toto, thank God,” he says, referring to his heated, bidet-rigged Japanese toilet.

For the first time in decades, he was rooted in one place, and he made the most of it. He worked out, a lot. As spring arrived, he observed nature’s transformation. “The buds started to come, and I tracked that,” he says. “Birds started to arrive in the backyard. Like, squirrels were behaving differently.”

Still, it was a lonely existence for a man who thrives on connection. Though he’s seen a few close friends—Amy Sedaris, the fashion designer Adam Selman—he “can’t wait to hang out with more than three people at a time.” When filming for The Mosquito Coast resumed last fall, Theroux went back to Mexico. Human contact! Not with three people, but thirty! “But that’s a work environment,” he says. “It’s social, but not the social I want.” They wrapped in December, and he’s been in New York City ever since.

“I don’t want to become a hermit. At all,” he says. “What I’m most thirsty for now is friendship. Once that’s up and running, I’ll start thinking about the other stuff.” By “the other stuff,” he means romance. Officially, he is single, and has been since he and Jennifer Aniston divorced in 2018. Before they got together in 2011, he was in a relationship for fourteen years with the stylist Heidi Bivens. This is the first time, in other words, that Justin Theroux has been single since the Clinton administration.

Dating after seven years as half of one of Hollywood’s most famous couples presents unique challenges. Each time Theroux appears in public with a woman, any woman, it becomes tabloid fodder. Not that there have been many opportunities over the past year. “All the avenues to dating”—by which he means his avenues—“are completely shut.” He doesn’t use dating apps. “Never.” Nor has he slid into someone’s DMs; he says he’s unaware of anyone who’s slid into his. “Sounds a little old-fashioned, but I actually like to get to know someone,” he says in an affected, self-mocking register. “That’s the fun of meeting people. Sussing them out and playing... not games, but—” He stops himself. Slackens his face. His black brows settle from their expressive arch. “It all sounds predatory when I say it.” His voice gets low, gravelly, and, well, predacious. “The strategy. The game.”

But his point is taken: Theroux, who turns fifty in August, is not dating right now. “There’s only one pivotal relationship in my life,” he says, grinning as he finishes the thought. “My mom.”

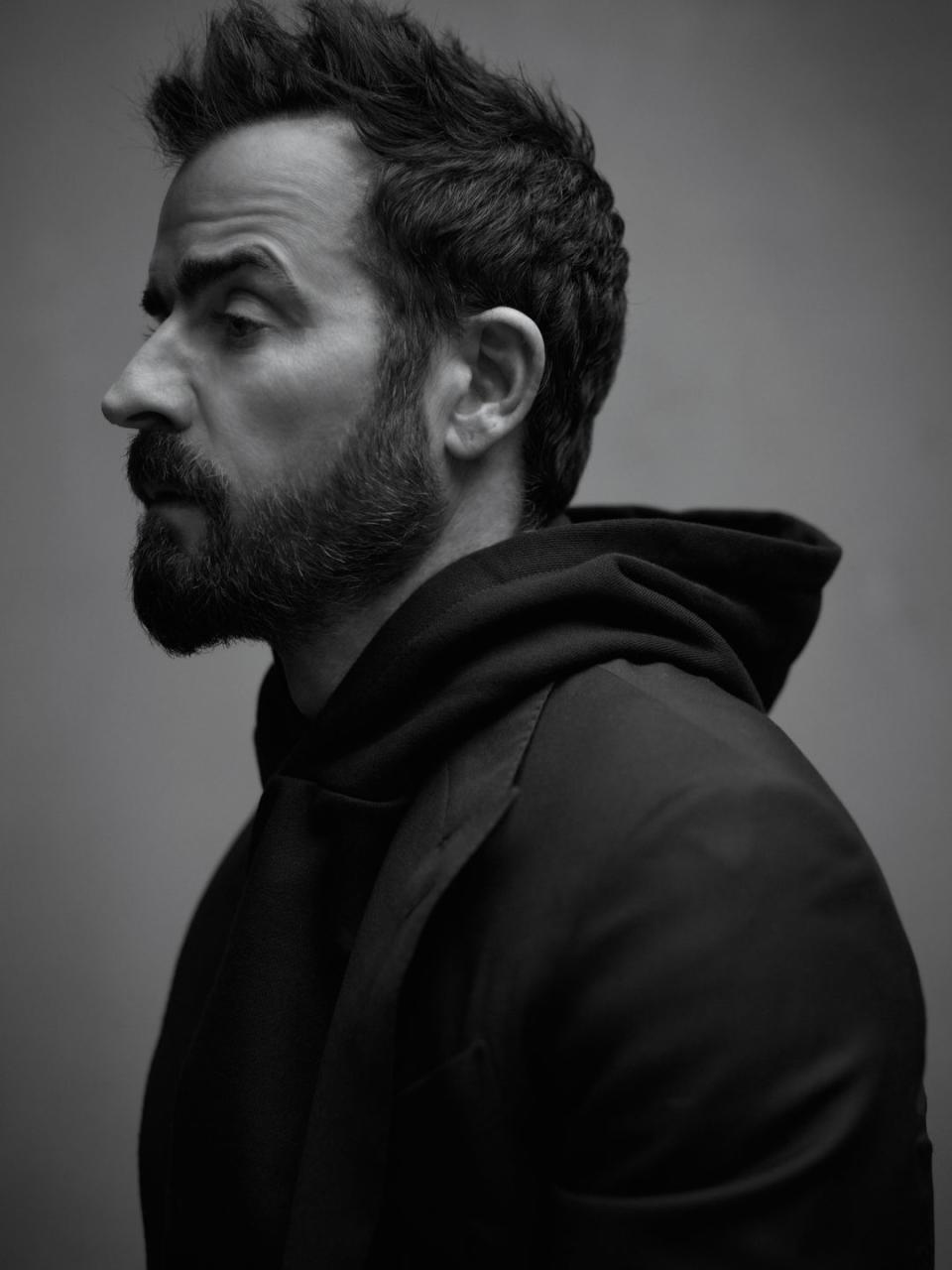

Two days after our Zoom call, Theroux and I meet for lunch at the Smile, a subterranean café that’s nursed the hangovers of downtown scenesters for a dozen years. He arrives in all black—a military-style backpack, R13 boots, John Elliott pants, a Maharishi sweater to which he’s affixed a train of fabric with dozens of safety pins. On a gold chain around his neck hangs an old New York subway token that he got at a flea market, a little piece of his hometown he carries with him everywhere.

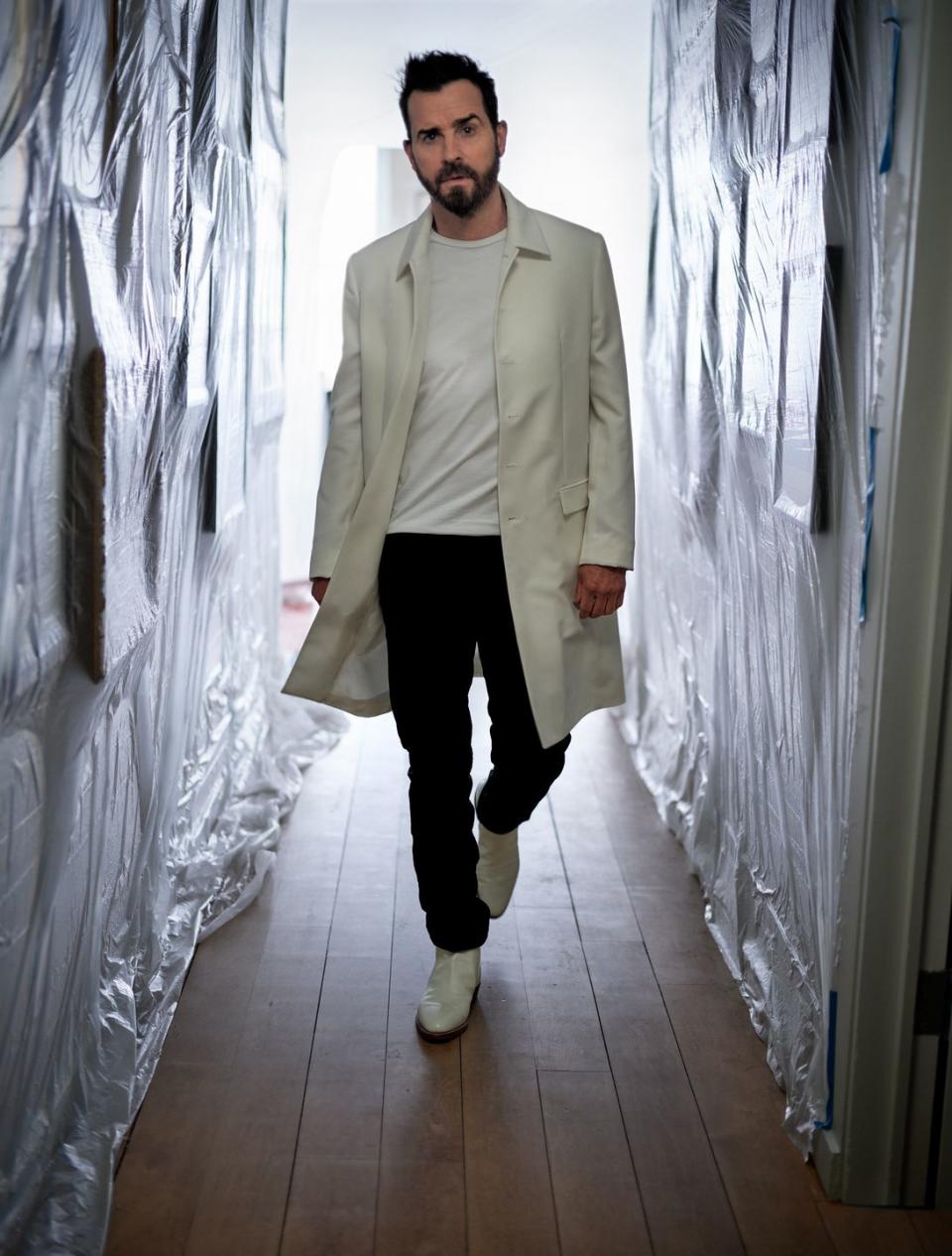

Coat and T-shirt by Dior Men; jeans by Rag & Bone; boots by R. M. WilliamsMark Seliger

We settle at a table under a shedlike structure outside, one of the thousands now occupying parking lanes all over the city. He orders a pot of green tea, a cup of oatmeal, and a breakfast sandwich, hold the ham. He loves this place, has been here more than any other restaurant. He’s close with one of the owners; the summer before the pandemic began, they and a few other partners opened Ray’s, a nearby “dive-themed” bar where you can get a shot-and-beer special that costs twice as much as it would at an actual dive. Theroux feels comfortable here. During these trying times, “you have to find the cozy places that feel like extensions of your own home,” he says. “This is one of those places.”

Nestled in this safe space, engaged in an actual in-person conversation, he opens up about his marriage. When he and Aniston announced their separation, they didn’t offer a reason to the general public, but that didn’t stop the world from wondering. The explanation drummed up by and echoed in the entertainment press was that she wanted to live in Los Angeles and he wanted to be in New York. “That’s a narrative that is not true, for the most part,” Theroux says. “Look, people create narratives that make themselves feel better or simplify things for them. That whole ‘This person likes rock ’n’ roll, that person likes jazz.Of course!’ That’s just not the case. It’s an oversimplification.” He declines to elaborate.

This article appears in the April/May 2021 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

The week before, he posted an image of Aniston on Instagram, wishing her a happy birthday. I ask if they’re on good terms, as the post suggests. “I would say we’ve remained friends,” he says. I ask how, and he takes my question to be about the medium, not the message. “We don’t talk every day, but we call each other. We FaceTime. We text.” I clarify: How does he navigate the complicated emotional terrain left between two people who committed their lives to each other and then rescinded? “Like it or not, we didn’t have that dramatic split, and we love each other,” he says. “I’m sincere when I say that I cherish our friendship. We can not be together and still bring each other joy and friendship. Also, she makes me laugh very, very hard. She’s a hilarious person. It would be a loss if we weren’t in contact, for me personally. And I’d like to think the same for her.”

Still, he hasn’t exactly answered the question. I point out that most people don’t stay in touch with their exes—the pain on one or both sides renders communication, let alone friendship, too much to bear. Time passes, the emotional ties weaken, and life moves on. He nods in recognition. “I think that when you get good at relationships—and here I am, single—if you love the person the same way you loved them in the relationship, it would behoove you to love them the same way out of the relationship,” he says. “Who wants to take a shit while you’re walking out the door?”

Theroux and Aniston share a large group of friends—Jimmy and Molly Kimmel; Jason Bateman and his wife, Amanda Anka; Will Arnett. When their marriage ended, no one had to choose sides. “In a lot of ways, it’s kind of seamless,” Arnett tells me. “It speaks volumes about both of them. When you’ve been with somebody in that way, you’ll always be connected. And it’s hats off to them for how much attention they give that, and how important it is to both of them to maintain that love. I think it’s really remarkable.” He also finds Theroux’s “seemingly ageless” physique remarkable. “If I could torture Justin, I’d have some guys pull up in an unmarked van, grab him, take him to an undisclosed location, and make him eat dessert on camera. I haven’t seen the guy eat a dessert in at least ten years. I mean, he looks phenomenal.”

A few days before our lunch was the third anniversary of their divorce announcement. That day, just like all other days, Theroux took Kuma out for a bathroom break. The next day, the Daily Mail ran photos of their walk under the headline "Jennifer Aniston’s Ex-Husband Justin Theroux Cuts a Lonely Figure in NYC." He swats away the notion that such attention affects him in any way. And yet it does. “A friend of mine comes to the park over here with his toddler all the time,” he says, gesturing east. “I would love to go hang out. But I don’t want to subject him, and certainly not his kid, to people photographing. I won’t do that.”

What about kids of his own? “I don’t feel that compulsion. I don’t have a resistance to it, but I don’t have an eagerness for it,” he says. “As for wanting to continue the family line, there are plenty of Therouxs in the world who can do that for me. They’re doing a great job popping out kids.” He thinks for a second and runs his hand down his beard, reconsidering. “It would be kind of great if I got a knock on the door and someone said, ‘Hey, I’m your sixteen-year-old kid.’ I’d be like, ‘Oh my God, it’s amazing.’ ”

Unlike her son, Phyllis Theroux, eighty-two, does not eschew online dating. Almost thirty years after she divorced Theroux’s father, Eugene, she married a man she met on Match.com—but not without reservations. In her 2010 memoir, The Journal Keeper, the essayist and former New York Times contributor wrote, “Could the conventions of society, wanting to be like the others, be at the bottom of my decision? Can I be someone’s partner and still be free?... Justin, ever vigilant, phones me daily to take my emotional temperature.”

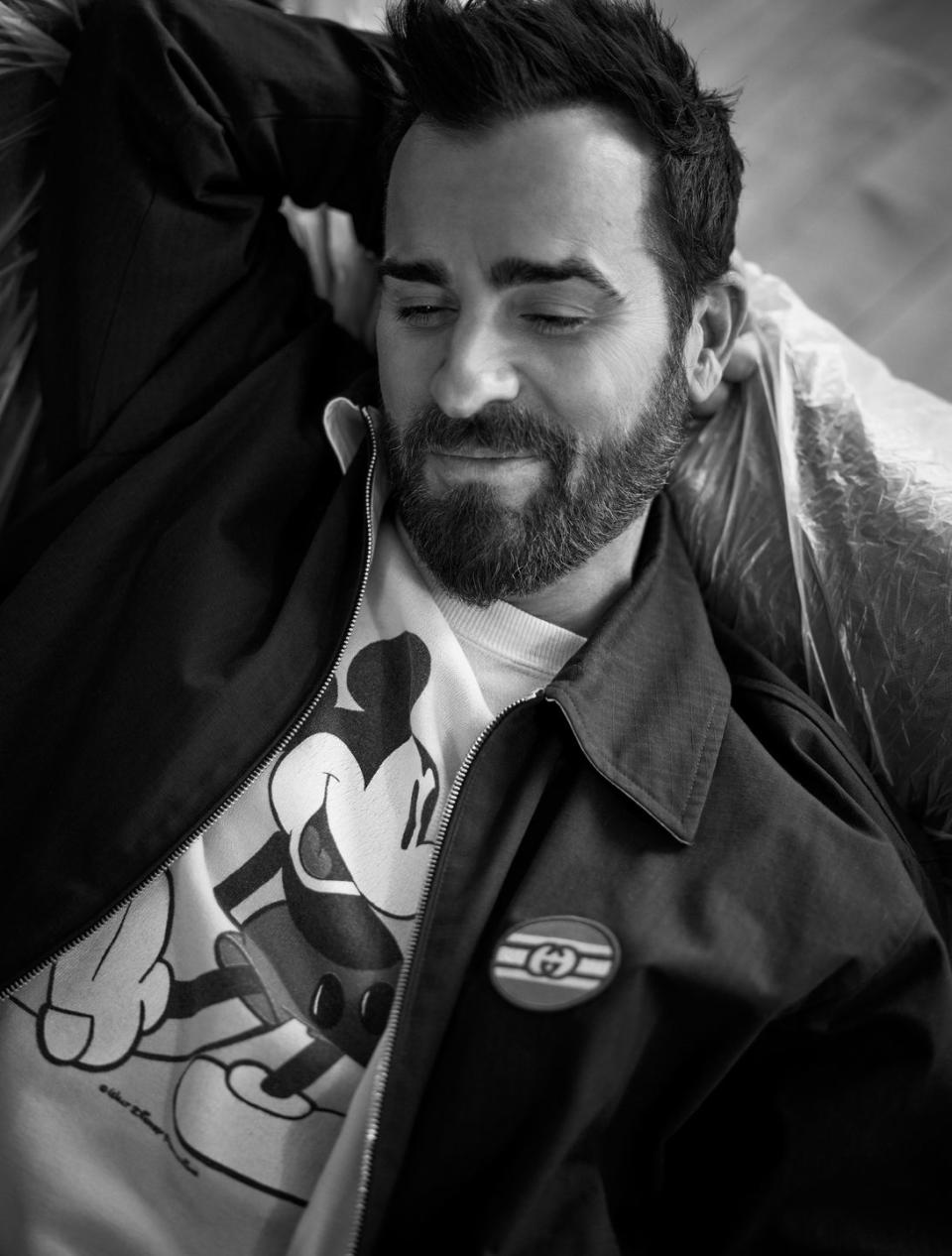

Jacket by Gucci; vintage T-shirt from the Society Archive.Mark Seliger

Theroux, the youngest of three, grew up in Washington, D. C. Eugene, now retired, was an international trade lawyer who specialized in introducing American businesses to communist countries; he helped bring Kentucky Fried Chicken to China and Pizza Hut to the Soviet Union. Eugene’s brother Paul, a travel writer and the author of The Mosquito Coast, the novel from which his nephew’s new show is adapted, describes the Therouxs as “a family of rivals, satirists, mockers, teasers, and gossips. We were very, very combative, very rivalrous. In a family of competitive people, they’re always trying to tease you or tear you down, doubting you or testing you.” And, he says, “Justin was tested.” Theroux did poorly in school. He was scrawny, and he hit puberty late, around fifteen. He was also a frequent target of the family’s teasing. “The only thing Justin’s known for,” Paul says—not one thing, but the only thing—“is that when he was a boy, he ate a Styrofoam cup. It’s family lore: Hey, shit, Justin won an Emmy! Remember the time he ate a Styrofoam cup and then puked it onto his shoes?”

Theroux was six when Phyllis and Eugene divorced. It was messy, and the children were caught in the middle. Dad fed them sugary cereal at his house, and Mom did not. Mom retained custody, and Dad threatened to sue over it. “Now, at least reflected in the friends I know who are getting a divorce, the idea is that no matter how rough the waters get, or how badly you’re drowning, you will always hold the kids above your head to make sure they don’t get wet,” Theroux says. “That did not happen in the seventies.” He says of the impact on him and his siblings, “You can’t fathom it. It’s like gravity stopping to exist.”

“Justin needed to get away from the family to succeed,” Paul says. “They would’ve stifled him.” Theroux got away. He studied art and theater at Bennington College, that liberal bastion in southern Vermont; he moved to New York and started building a career. He says that he and his father are now on decent terms. “We treat each other with great care,” he says. “It’s steady work. There is no going back to play catch in the street.”

Last March, Phyllis’s second husband, Ragan Phillips, died after an extended stay in hospice. After months of caring for him, she learned that there would be no funeral because of the emerging pandemic. In lieu of a memorial service, friends surrounded their home with votive candles. “It was an added level of grief that was heartbreaking for me to witness,” Theroux says. “To have her house be vacant, and to not have the rituals and the support systems that normally would sweep through it, with love, and food, and company—it was just terrible.”

Theroux says Phyllis is “sharp as a tack” but that her husband’s death sent her spiraling. She was lost in a mournful fog that presented as a sort of disorientation, “like she’d lost IQ points.” She turned inward, which terrified her son. As before, he called every day to check in. He taught her to use Zoom and FaceTime. He gently pleaded with her to recognize that she was depressed. A month passed, then two, with little progress. Then, says Theroux, “something miraculous happened.” As she sorted through her husband’s possessions, Phyllis found a journal he had kept. She called her son, elated. “She said, ‘It’s almost like in death, our relationship is deepening,’ ” Theroux recalls. In this way, she transcended her grief. “She became this lotus, pushing through the mud to lay its leaves on the surface,” he says, choking up at the memory. “They had a deep love for one another that I admire so much.”

His parents’ partnership offered a young Theroux no such model of unconditional love. “Early on, I went into relationships very cautiously,” he says. “I had to navigate, and still have to navigate, how to have relationships and communicate and be an adult.” He dated; he got dumped; he dated some more. “You meet different kinds of women in your life, who teach you different lessons about what gives you the best chances of success with being satisfied in a relationship.” To wit: “The only relationship where I think codependency should be totally encouraged is with a dog.”

Theroux has not played many fathers. One of the first times he did, as the titular character’s dad in Megamind, came nearly fifteen years into his career. He did so again on HBO’s The Leftovers. On The Mosquito Coast, which premieres April 30, he stars as a family man and a fugitive from the U. S. government who absconds across the southern border with his wife (Melissa George) and their two children in tow. That’s about it.

But the love interest—that’s a role Theroux knows well: He first appeared onscreen in 1996, as a ratty revolutionary who sleeps with the woman who shot Andy Warhol in I Shot Andy Warhol. He went on to play a refined cowboy in Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion, a smarmy lawyer on Ally McBeal, a dorky councilman on Spin City, a Bondian spy on Alias, a French-horn player on Six Feet Under, and not one but two not-right-for-Carrie dates on Sex and the City, including a premature ejaculator named Vaughn Wysel.

He might have been typecast as the love interest forever were it not for his role in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. Theroux plays a smug director who’s easy to hate, with his Porsche Boxster, his slight frame lost in the folds of ill-fitting fashion of the late nineties, and his white-guy entitlement, but who earns your sympathy by the end. It’s among Theroux’s most memorable performances, and it underscores the albatross that has in many ways defined his career: He is a character actor, with the considerable chops that requires, but he looks like a leading man.

Jacket and T-shirt by Dolce & Gabbana; vintage trousers and necklace, his ownMark Seliger

Victoria Thomas, the casting director for The Mosquito Coast, describes Theroux’s niche like so: “He’s a smart guy, a hot guy, easy on the eyes. He’s a dramatic actor, but he can tell a joke,” she says. “You believe he could exist on both sides of the law. It’s nice not to be able to know what you’re getting in every performance.” But she acknowledges the inherent challenges of a versatile actor. “People don’t know how to pigeonhole you in an industry where sometimes people want to pigeonhole you.”

“Justin looking and sounding the way that he does, instantly the town decides, ‘We’re going to groom this guy to be the star of a Marvel movie,’” says producer and screenwriter Damon Lindelof. “There’s a reason that you look at his filmography and there aren’t twenty-five movies and TV shows that he’s worked on. It isn’t for a lack of opportunity. It’s because he’s very selective about what he chooses to do. When we were casting Lost, he was definitely on the Jack list. He wasn’t interested.”

Lindelof recalls learning that Theroux had cowritten the screenplay for the gutsy, hilarious Hollywood satire Tropic Thunder. “It was like, ‘Oh my God, Justin Theroux’s a comedy writer?’ ” Years later, Lindelof had reservations when he first considered Theroux for the lead role on The Leftovers. “I was like, ‘That guy is way too good-looking to pull it off,’ ” Lindelof says. “Then he came in and read, and I was like, ‘This guy is a very, very, very good actor, in spite of his good looks.’ ”

Early buzz for the show did not center on Theroux’s acting but rather on his anatomy. In 2013, while filming a scene for the pilot, he was jogging in a pair of gray sweatpants that left little of his genitalia to the imagination. Tabloids ran the photographic evidence. The sweatpants became a meme—not with such virality that it overshadowed the series, but with enough intrigue for it to linger. The writers made it a running joke throughout the otherwise serious drama, with references subtle and not subtle at all. In 2017, during the Emmy campaign for The Leftovers’ third and final season, Lindelof posted steamy stills from the series on which he’d written messages like “Nominate Theroux and the sweatpants go away.” Theroux seemed to be a good sport about the whole thing—he joked about it on late-night television, and he played along when, for example, a scene in season 3 featured a penis scanner and a cringey pun about length. “At the time, I just thought it was so funny that in a business and a culture that is constantly objectifying women, they were objectifying Justin,” Lindelof says. “Now, in 2021, I look back and it feels pretty yucky.”

Theroux didn’t get the Emmy nod. But he did receive an apology from Lindelof, who felt tortured even then. “Justin and I were friends—are friends—but I was also his boss. It was my job to protect him instead of saying, ‘Look at how funny it is that everybody is talking about your dick.’ ”

The actor took it all in stride. “It didn’t feel great. I don’t want it to happen again. But I wasn’t traumatized by it,” he says. “Look, I’m not saying objectification doesn’t happen to men—of course it does. But there’s a kind of scrutiny that’s placed on women that isn’t placed on men. I have no idea what it feels like to have someone sell naked photos of me online. That kind of violation, I mean, I don’t know if I’d get over it. And it’s happened to women since forever. I think I have more sympathy for them than for myself.”

As we finish lunch, our conversation returns to Theroux’s most important relationship, the one with his mom, and a call they had last Mother’s Day.

Coat by Alexander McQueen; vintage T-shirt from the Society Archive; jeans by Nudie Jeans; boots by R13.Mark Seliger

I had read a column Phyllis wrote about Mother’s Day 1979 for The New York Times. On that day, at six in the morning, her daughter woke her to say that Theroux, then seven, wasn’t in his bed. “The youngest is a born rider of the rails,” Phyllis writes. “He thinks up reasons to run away, just for the thrill of it.” She ran downstairs and found no sign of him. “I went to the telephone, dialed the police, and lived out my worst fear—I put in a missing-child report.” As officers made their way over, Phyllis thought to check one more place: the community garden where she kept a plot. As she drove there, she spotted her son, barefoot, in his pajamas. She ushered him into the car and demanded to know why he’d left. “ ‘Because,’ he sobbed, ‘I woke up and remembered it was Mother’s Day and I didn’t have a present. And I thought maybe I could find some flowers to pick. But when I got to Oregon Avenue, I remembered I wasn’t allowed to cross it by myself.’ ” She forgave him and said they should get home to tell the police. Suddenly Theroux stopped sulking. “His face took on an intensely interested expression,” Phyllis writes. “The tragedy of Mother’s Day had been supplanted by a more interesting thought line.”

Mother’s Day 2020 came at the height of the pandemic, shortly after Phyllis’s husband died. “It had been such a tough year for her, and I wanted to tell her how much I loved her,” Theroux says. “Not just ‘Hey, Mom, Happy Mother’s Day. I love you.’ I really wanted to impress on her how valuable she is to me. I wanted to express in a completely unfettered way how much I loved her.” At one point, he explained that two months in quarantine had made him feel as if he’d lost a year of his life. “She was like, ‘You feel like you’ve lost a year? I don’t know how many more of these years I have left,’ ” he says. “That scared the shit out of me. Fuck my career, what I want to accomplish, my legacy, all that. It made me think, Oh my God, I’ve got to pay more attention to the things that are important.” Family. Friends. Love. “I want partnership,” he says. “Like everybody.”

Photographs by Mark Seliger. Styling by Nick Sullivan. Casting by Randi Peck.

You Might Also Like