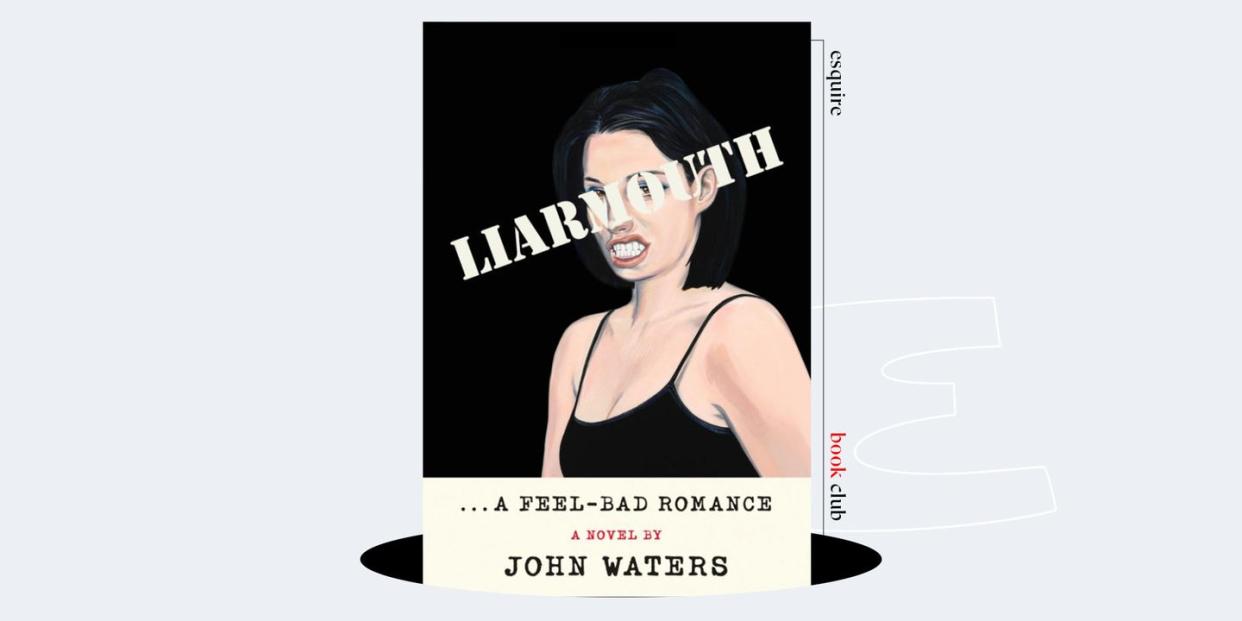

John Waters Is Still Here For Good, Unclean Fun

At 76 years old, there’s not much John Waters hasn’t tried. The legendary Pope of Trash has battled censorship, dropped acid, and hitchhiked across America, but until recently, one thing eluded him: writing a novel.

His debut in the format arrives today, and it’s a characteristically Waters-ian phantasmagoria of good, unclean fun. The filmmaker, writer, and artist takes his first bow. with Liarmouth, a "perfectly perverted feel-bad romance” about Marsha “Liarmouth” Sprinkle, a con woman caught up in a bad romance with Darryl, the degenerate loser with whom she steals suitcases from airport luggage carousels. Marsha has promised Darryl sex for his services after one year of employment, but when she skips out without paying up, Darryl is out for revenge. Their cat-and-mouse caper brings them into contact with unforgettable characters like Marsha’s mother Adora, who runs a dog facelift clinic; Richard, Darryl’s talking penis; and Poppy, Marsha’s trampoline-addicted daughter, who’s also the leader of a cult for bouncing enthusiasts.

In his acknowledgments, Waters aptly describes how, in writing Liarmouth, he risked veering into “fictitious anarchy.” That’s as good a description as any for this campy, raunchy, surreal story, rife with ribald pleasures. Ahead of the work's release, Waters spoke with Esquire by phone from his home in Provincetown, where the conversation ranged from eargasms to travel tips to the state of American comedy. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Esquire: Where did Liarmouth begin for you, and how did it take shape over time?

John Waters: Ten or fifteen years ago, the part about a woman stealing suitcases started as a movie idea. I’ve always wanted to write a novel because I love to read novels. I've written fiction my whole life—all my movies are fiction. Liarmouth evolved from there. But it’s a very, very different time for humor now than it was when I started the book. We purposely became our own ludicrous sensitivity editors here in my office, where three generations of women work. They’re all excellent copy editors. We all went through the book knowing that it’s making fun of political correctness, but at the same time, what’s the edge you can walk on? I still don't know if I fell off the edge or not.

The writer Bruce Wagner told me about sensitivity editors, which I had never heard of before. The very words "sensitivity editor" are a trigger warning for me. We sent the book to a sensitivity editor, but she never called back and wouldn't take our calls. I don't know what that means. Is that a good review from a sensitivity editor? To my publisher's credit, we just moved on and didn’t send it to another one. We became our own sensitivity editors. I think we've made it so ridiculously politically correct, sometimes. Is there ever a limit to what a minority has to be in order to get their rights? In this book, I go to great lengths to make fun of that and embrace it.

How would you describe this time for humor?

If this book came out in the '60s, I'd probably go to jail, because right-wing people would want to put me there. If I get in any trouble today—and I don't expect to—it would be because of left-wing, politically correct, self-righteous students. I fought for free speech. I think that anybody should be able to say anything, even if it's odious. If you don’t like it, don’t listen. I make fun of things I love, and I've always made fun of the rules of the world that I live in, which is never mainstream and always alternative. But those rules are sometimes even more stringent than the ones I was raised with, so I like to point that out every once in a while.

I think about this often—what’s the line between art that’s offensive, and art that’s simply not intended for me? Take, for example, the characters in the book who wear shirts emblazoned with the words, “I eat ass.” If readers are offended by that, perhaps this isn’t the book for them.

I actually saw a person walking down the street with that shirt on. I like to think about how he bought that shirt and thought, “This would be perfect for Provincetown.” Parents were scandalized because a four-year-old could read that sentence. I wondered, "What is he thinking about?" That’s what this whole book is about: people whose behavior is hard to understand. I'm fascinated by human behavior, even devious and obsessional behavior, where it seems totally normal to this person, who doesn’t understand why you think it's bizarre.

We as a culture seem to be edging us toward this territory where we expect characters to reflect our ideals, and to be good, upstanding people. But art is no fun if everybody's good.

It’s not. My world has always been cockeyed—the villains are always the heroes. Marsha is a villain, but you root for her. Her behavior is terrible, but she changes, too. She learns a few lessons, but doesn’t apologize.

Marsha is such an enthralling, confounding character. How did you find her voice?

Every character in this book lives somewhere inside me. I'm always thinking up characters. As a writer, I just sit in an airport, watch people get off a plane, and make up a ten-second biography of each person as they walk by. My friends always say, "Just stop asking questions." But I can’t stop, because underneath everything, all writers have to ask questions to find out how people think.

So much of the fun of Marsha is her comic delight in lying. Have you ever encountered anyone who shares that quality?

I do know somebody that tells practice lies, almost as an exercise. She just can't tell the truth. Marsha believes that lying grows her power and makes her prettier, and she just likes the process of lying. She likes to see the ripples of disbelief as she walks away—which means that she's an anarchist, in a way, because she lies for no reason.

My favorite of her lies was when she tells a group of children that the Jonas Brothers had been violently beheaded in a car accident.

I've met the Jonas Brothers before, and I liked them. I just tried to pick someone that would make readers laugh.

What’s one of the greatest lies you've ever told?

Well, you always lie backstage at the theater, don't you? It’s called green room perjury. If you really didn't like the play and your friends are in it, you have to lie and say that you loved it. That doesn't happen to me often, but I’ve definitely done it.

So often, your work revels in the carnal joy of sex, but Marsha finds sex to be utterly distasteful. What was it like to write from that viewpoint?

The most radical thing you could say nowadays is, “I love sex." You need five lawyers to ask somebody on a date. Marsha is beyond political correctness. She hates sex. She hates the idea of intimacy with any man. She has good reasons to be bitter about sex, but she’s well beyond the views of radical feminists like Andrea Dworkin, who argued that all heterosexual sex is rape. I love women who hate men, and I hate men who hate women. I'm an old lesbro from way back. I think gay men forget how much we have to thank lesbians for, because they started Act Up when their friends were dying of AIDS. I've always been big on the most insane sexual politics, even if I don't agree—I just like hearing about them.

This brings us, of course, to Richard the talking penis. This part of the book struck me as very much in conversation with what’s happening in pop culture, where we’re seeing more penises on screen than ever before. Have you clocked this too?

There have been talking dicks in books and movies before, but there's never been a gay dick on a straight guy, like Richard and his owner. But suddenly, there are dicks everywhere. One of my favorite scenes was in Red Rocket, when Simon Rex is running through the streets naked. But it's weirder now, because to be politically correct in movies, there has to be an intimacy expert. I think we should make a movie out of Liarmouth, though it would have to get an NC-17 rating—isn't it time, finally, to have an NC-17 hit movie again? They’re so afraid of that. Today, you have intimacy experts, which are to film as sensitivity editors are to books. It's just a new word for censorship, basically. On the set of A Dirty Shame, a movie I made about sex acts, we had scenes where all the extras had to make out for hours, and then they'd just start laughing. I don't think I was exploiting anybody, and they didn't either. But today, you'd have fifty people on set monitoring that. I guess that's good, in the long run. I hated filming sex scenes. They're embarrassing.

You’d think that in the age of streaming, it would be a golden age of NC-17 movies, given that the streamers have endless funding and can bypass theaters.

That’s the battle. The true war of movie terror is going to be when Netflix raids NATO's office about day and release patterns, or when they start delivering popcorn by Uber cheaper than the theaters. But I'm not against any of it, because as long as there are more places that can say yes to making movies, I'm all for it.

Liarmouth is steeped in cutting insights about the indignities of travel. What are your hang-ups as a traveler?

Every flight is packed. Then there’s the mask war, where both sides are pissed. I’ve never seen anybody duct-taped to the seat, but I want to. It’s pretty clear that one day I'm going to get duct-taped to the seat because of what other people do on airplanes. I’m on airplanes every day, so it's not hard to imagine. I knew someone years ago that used to always steal the flight attendant's pocketbook, because it's always in the same place when you walk on the plane. One time, my friend was with that person, and when the plane landed, the flight attendants said, "No one is getting off this plane until we get this pocketbook back." Everyone was screwed until someone snitched. That gave me an idea for this book, too.

What's your best travel tip?

Always get there early. I’m so early for flights. I want to be first on the plane and the first off the plane. That's why I like aisle seats. I like flying because no one can contact me. You're unreachable for a certain amount of time. I have a fear of not flying, because that means I have to stay home all the time, which is what Covid was. Also: always have a book with a title that makes people not want to talk to you. I always have so many books and magazines. I still get over a hundred magazines in the mail, and I’ll have $300 worth of magazines with me on the plane. When I’ve finished one, I’ll say to somebody, "Would you like a magazine?" They act like you asked them to hold a turd. But I do tear off my address label before I leave anything on an airplane. Like Marsha, anyone could build a false identity.

Another place your sensibility comes through in the novel are the homes where Marsha squats, which she describes as "rich yet possessionless, fancy but hardly to the manor-born, a style no one could call their own." I get the sense that perhaps you dislike McMansions.

I think they're the worst possible home you could have. They make me think of “hair-hoppers,” a word we invented in Baltimore. It's somebody that really doesn't have as much money as they say. They try to act rich and spend way too much time on their hair. Trump is the ultimate hair-hopper. The term used to be about women with giant hairstyles, but we don’t live in that world anymore.

I love older women who still go to the beauty shop to get their hair done every week.

My mom went all the time. She didn't have a high hairdo, but she went to get it set. I think women love that. I always hated going to the barbershop; I was sentenced to go by school officials because I had long hair. The barbershop was second to the draft board on my enemy list. Now the person that cuts my hair comes to my house. I don't like sitting in a barbershop where they talk about sports and have calendars with naked women.

In the acknowledgements, you mention the risk of Liarmouth becoming “fictitious anarchy.” I found that term so interesting. What would've turned the book into fictitious anarchy?

Well, there’s some fictitious anarchy in the book. Like the scene at the dog facelift salon—it’s anarchy, but it's comic anarchy. It’s more like an action movie gone crazy. People are flying through the air and landing on coffee tables. They're trying to land on Marsha. They’re bouncing around and hitting the ceiling. Of course there’s no cult like the bouncers, but there are some close to it. Bouncing is a fetish. It's a movement. I know people that are addicted to riding bicycles, and people who are addicted to jumping on the trampoline. What’s one step further?

So much of your work revels in that boundary. What makes one predilection more acceptable than the other?

It’s acceptable if people can understand it themselves, even if they don't share it. What interests me is when they can't. Any cult, when it's good, brings people great happiness. They feel that they know something you don't know, which is what all religions are. It looks like fun to jump on a table, but I can't imagine it being so much fun that you’d never want to stop jumping. I would respect people who were crazy enough to commit to this behavior that leaves them totally misunderstood, but really, they could never go anywhere if they're always bouncing up and down. In the book, a child asks, "Why are they doing that?" And the parent says, "She's just excited." I like to see the so-called liberal reaction to unimaginable behavior. When is there a line? Is there a limit to that? That’s what this book is about.

You’ve said that a book called Ear Masturbation was quite inspirational during the writing of Liarmouth. How so?

I don’t know how this book ended up in my library, but I found it, and it did inspire one of the scenes. I don't know if this book is funny or serious. It’s a book all about ear masturbation, which I had never heard of before I encountered it. As a matter of fact, when we hang up, I'm going to the ear doctor, so maybe today I'll have an eargasm. I had never heard of that term, but it gave me great freedom to write about ludicrous sex. Is there such a thing as an eargasm? I do know that all ear doctors say what’s made them rich is Q-tips. That's the very worst thing you can stuff in your ear, and that's the very first thing people do. Are Q-tips the training wheels for eargasms? I’ve never met a person who’s serious about this, but it certainly opens Marsha up to new experimentation.

Liarmouth was your first foray into novel-writing—are you open to writing another one?

I definitely am. I don't know what the next book I'm going to write is—if it'll be essays or another novel. I think a lot will have to do with how this book is received. This book took three years to write, but at the end of the day, I just wanted to make people laugh.

You Might Also Like