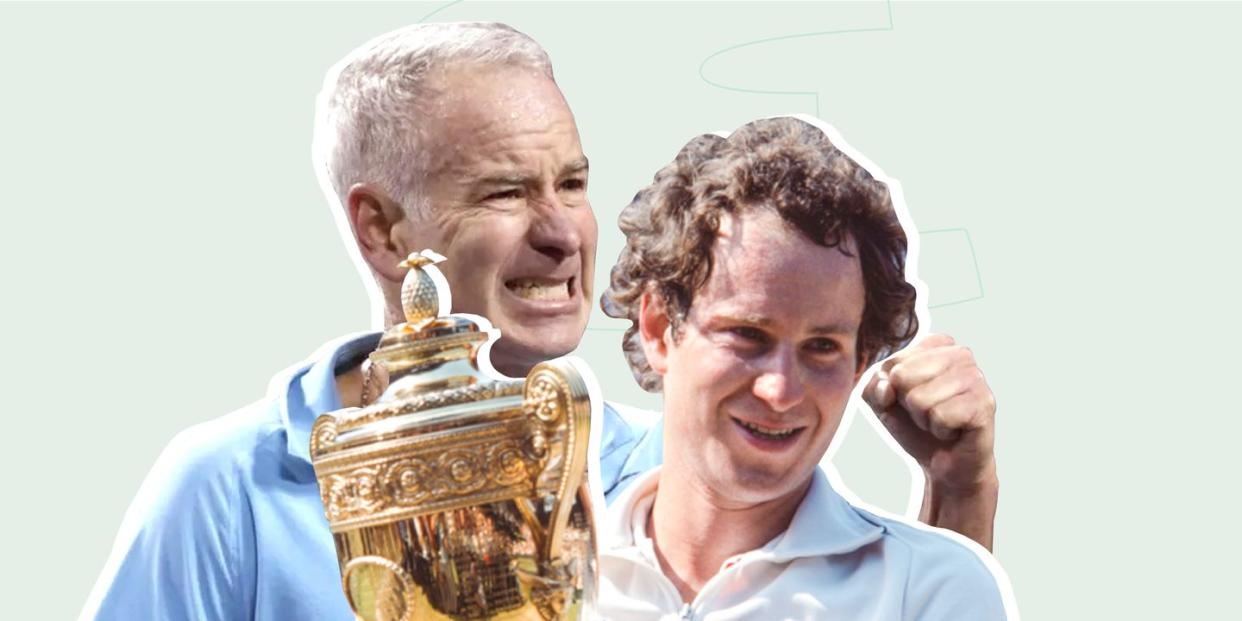

John McEnroe and a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Asshole

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

John McEnroe was famous for three things: being a champion, artist, and an asshole. Though not necessarily in that order. The number one player in the world for four years (1981-’84) at a time when the game surged in popularity in the U.S.—and eventual winner of seven grand slam titles—McEnroe featured a serve-and-volley game that was as thrilling as it was brilliant. But his on-court genius was undermined by an inability to control his temper—McEnroe wasn’t dubbed “Superbrat” by the British press for nothing. And while he often harnessed his fury and played at an elite level, in the end, it got the better of him. Outside of the game, he’s better remembered as the dude who bawled, “You cannot be serious!”

In the dutiful new Showtime documentary, McEnroe, the prodigy from Douglaston, Queens, admits that he did a “shitty” job of handling tennis greatness. In the documentary, which premieres tonight at 8 p.m. ET, the filmmakers attempt to examine the psychological and emotional underpinnings of the athlete's personality. Particularly, McEnroe's contentious relationship with his father. The essential trouble is that, while McEnroe is a veteran TV commentator, he lacks the gift of introspection. (“I don’t like to look back very much,” he says.) This isn’t unusual for a performer of his caliber, but if you're expecting to find the candor and revelation that made Andre Agassi’s 2009 memoir, Open, so riveting, McEnroe, is a portentous, if skillfully-made, bit of hagiography.

A generation ago, biographical portraits of entertainers or athletes were largely the domain of magazines and newspapers. In the early ’80s, for instance, if Sports Illustrated wanted to put McEnroe on the cover, that could lead to an endorsement deal or two for a young star. So it behooved them to let a writer—a writer!—hang around for a week and then go off and write the story as the publication saw fit. The subject was then at the mercy of the writer and the publication. While this led to a slew of fascinating stories for the reading public—and, to be fair, plenty of tacky, obnoxious, and forgettable stories—it usually meant agita and grief for the subject.

These days, the paradigm is flipped, so we get documentaries such as Legacy: The True Story of the Lakers, or The Last Dance, where the subject has a hand in the production. Who can blame them? Why should they leave their legacy up to someone else? (Unlike many sports docs, McEnroe does away with interviewing sportswriters entirely.)

The biggest losers are us, of course, because what we’re left with is thin, no matter how adorned with fantastic production values and computer animation. Such is the case with McEnroe, where much effort is spent amping up the visuals due to a lack of substance. We’re presented with McEnroe today, wandering around the city, as a kind of Dark Knight haunting Gotham in the wee hours of the morning. He’s a solitary figure, this former Prince of the City, consumed by the dramas of his past. There’s no hint of irony, let alone humor, in this conceit. Watching the documentary, I couldn’t shake the feeling that a young Johnny Mac would treat anything as solemn and airless like a lob ball waiting to be gleefully smacked into his opponent’s neck.

It's too bad, because McEnroe was fun. Especially in the late ’70s, when his punk attitude rattled the stuffy tennis establishment—just as Keith Richards, who makes a pleasant appearance, attests. Director Barney Douglas does a deft job compiling footage of McEnroe miked up in his prime, both on the court and off. Here, we see the cynical New York wiseass in full flower. McEnroe was never clever or witty, but he could land a line, and had a pugilistic sense of comic timing. The only instances where we see that glimmer in McEnroe’s eye, similar to the spark his father shows in interviews as well, is in clips from his playing days. Otherwise, we're left with the Dark Knight walking the pre-dawn streets. Or even worse, down a desert landscape into an oncoming storm, as a way to frame the many dramatic episodes of his career.

If you don’t know about McEnroe’s career, we’re served a compact retelling of his greatest hits—the friendship with Vitas Gerulatis and early rivalry with Jimmy Connors. (I wish there had been more Jimbo.) There’s also McEnroe's rivalry and friendship with Bjorn Borg, which is handled in more detail in the excellent 2011, doc, Fire & Ice. Unsurprisingly, there is little on the charmless Ivan Lendl, who famously beat McEnroe in the 1985 French Open. At the time, Lendl represented the future of tennis—an almost monk-like devotion to training, fitness, and discipline. McEnroe’s first marriage, to actress Tatum O’Neal, is delicately handled. The most affecting moments in the documentary come from two of McEnroe’s children, Kevin and Emily. And McEnroe’s hard-partying days in the limelight, the drinking, the cocaine, are only briefly mentioned. We get more on the star's complicated relationship with his father, as well as his second marriage, to singer Patty Smythe, who reports that she was really frightened the first time she saw her husband’s temper. Back in 2017, McEnroe told Esquire that Smyth “has an even hotter temper than I do. It's funny, because everyone assumes that I'm the hothead, but I'm the one calming her down.” We don’t get that story—or many others—in McEnroe, which is tasked with giving us a pat narrative in just a few hours.

Turns out, McEnroe isn’t really an asshole. Not like Pete Rose was an asshole. Ever the lawyer’s son, McEnroe just couldn’t get over the need to be right. Iften, when he got on an umpire for making an incorrect call, McEnroe was right. So, was he a rude bastard the way he carried on? Or did he simply have the balls to stand up for himself when he was wronged, as any great competitor would? We might have felt embarrassment watching his tantrums, sure. But some of us could also see ourselves. How many of us are guilty of self-sabotage? If we can’t relate to being as supremely gifted as McEnroe, we sure can relate to getting in our own way.

McEnroe is no phony. You don’t get a sense that he’s being dishonest here. But McEnroe isn’t as much fun as it deserves to be. The film is at its best when it is living in the ’70s and ’80s, with clips of McEnroe quipping to tennis officials and reporters. Best of all are the slow-motion shots of McEnroe on the court, where his brand of tennis—must-see-TV at the time—defined his greatness as a competitor and as an artist.

You Might Also Like