‘John Lennon clocked me. There was a wild look in his eyes…’ – a 1960s pop insider tells all

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“This is going to be their next single. I’d love to know what you think of it…”

It was 1965, and I was in the office of Andrew Loog Oldham, a young, good-looking, sharply dressed music supremo. I had always thought I had youth on my side, but this was someone even younger – and already about as successful as it was possible to get. So when he called me up and asked if I’d be interested in working for him, I agreed to go and see him.

I’d been a promoter in the music business for seven years, working for Tony Hall at Decca for several of those. It was a good gig – a great one, in fact. Why on Earth would I want to change any of that?

But then the needle came down on the acetate. There was the briefest bit of crackle and then, whoomph, one of the most iconic riffs in the whole of rock ’n’ roll ripped through the speakers. “Da da, da-da-daah…” The song finished. Andrew lifted the needle off the record and turned to look at me. “Well?” he asked. “Would you like to come and work here?”

If someone had played you an advance copy of Satisfaction by the Rolling Stones at your job interview, what would you have said?

Working for the Stones in the mid-1960s was a heady cocktail of music, drugs, alcohol and excess. Later on, it became more about acid, and after that it was coke, but in the mid-1960s, dope was where it was at: West Indian and Moroccan hash. I used to get it from a couple of girls near my office. They were call girls, as it happened, and incredibly nice and helpful. I used to score off them, picking up a lump of hash and keeping it in my office drawer, along with the skins. Andrew had this euphemism he liked to use – “I think we need to talk to the promotions department about that” – which was my cue to start rolling.

Andrew’s office was in Ivor Court, just off Baker Street. Technically, it wasn’t meant to be an office and was actually registered as an apartment. In order to continue the conceit, he put a single bed in my office, just in case anyone ever asked. It was there for show. When I first started, I got into the office and put the lights on, only to discover a blinking and bleary Keith Richards staring out at me from under the covers.

“Oh, hello,” I said, not quite sure what to say. “How are you?”

Classic Keith, he groaned and said: “Ooh, OK.”

“Do you want me to wake you up later with a cup of tea?” I asked.

“Yeah, all right,” Keith said, turning back over.

I switched the lights off and shut the door behind me, unsure what I was to do for the rest of the morning. This sort of thing didn’t happen back at Decca. I left him until 1pm, at which point I brought him a cup of tea. He was now less growly and much more friendly – incredibly sweet, in fact.

Mick Jagger’s head appeared around the door. “Chrissie’s gone and locked me out of the flat,” he said, talking about his then girlfriend, model Chrissie Shrimpton. “Who are you, by the way?”

Soon after that, I saw a cat in the corridor. It was limping and clearly wasn’t well. I asked Andrew about it and he said it was called Louise and belonged to Charlie Watts and his wife Shirley. “Can you take it to the vet for me?”

I bundled the cat up and took it down to the vet, who immediately said he’d have to put her down. It didn’t seem like a good harbinger for the start of my Rolling Stones career to be the person who facilitated having the drummer’s cat put down, so I was directed to a miracle vet, who somehow put the limb back together, like a jigsaw puzzle, with wire and plaster. The operation cost me £25, which was a huge amount of money at the time, but when Charlie and Shirley returned, they were delighted. Charlie took one look at me and said to Shirley: “I think he is the gayest person I have ever met in my entire life.”

I was nine or 10 years old when I realised I was gay. I had this recurring daydream that a man would come along and rescue me. It was only when I looked up “homosexual” in the dictionary that things started to fall into place. “Persons attracted to members of the same sex,” I read. The penny dropped. In 1950s Eastbourne, with thousands of gay men in prison, it made sense to keep it a secret. The only person I told was my Aunty Gladys. Her response was simply: “We all have our crosses to bear.”

In Eastbourne, I used to hang out in the Golden Record Salon, owned by a guy called Bill Sapsford, who also worked in London for Decca Records. In 1958, when I was 16, he said there was a job going at Decca and asked me if I’d be interested. It was a golden ticket.

I started in the record sleeves department, chasing the progress of sleeve notes and artwork. After six months, I was made assistant label manager for London American Records, which Decca owned, choosing four tracks apiece by artists such as Little Richard, Fats Domino and the Everly Brothers to package into EPs. Then, when I was 19, Tony Hall gave me a job as a promoter.

I first came across the Beatles in 1963 at a BBC show called Pop Inn, where they were promoting Please Please Me. I’d often be there, catching up with other pluggers from the different record labels, swapping stories. The moment they walked into the green room, they lit the place up like thousand-watt light bulbs. John Lennon was the one I was wowed by, but he was intimidating. I started talking to him, then to George Harrison, who was naturally quieter but easier. When I explained that I was working for London American Records, George called Ringo Starr over.

“This guy,” – George pointed at me – “he knows all about the records we like, Ringo.”

He asked me what I liked at the moment. “There is a song I love called If You Gotta Make a Fool of Somebody by James Ray,” I replied.

George and Ringo’s faces lit up. “We love that song,” George said.

“Well, if you’re into that sort of stuff, I’m sure I can get you copies,” I said.

George and Ringo had a thing for soul and Motown. I made sure that every time they came back to their flat after another tour or TV show, there would be a pile of records waiting for them.

The other side of the promotions job was looking after the American artists when they came over to Britain. Roy Orbison had a thing about cars, and classic wartime German Mercedes in particular. He saw one of these Mercedes pull out from a side street and told me he wanted to buy it. So I ran down the street, waving my arms, flagging the car down. I was lucky the driver didn’t think I was a mugger or try to run me over. Roy came out of the cab to join me. The driver double-blinked again when he saw who it was. With his jet-black hair and glasses, Roy was instantly recognisable.

“Are you…?” Roy nodded. He bought the car.

Brenda Lee, it turned out, was the most fun person to go to the cinema with. I took her to a lunchtime showing of the Chubby Checker film Let’s Twist Again in Piccadilly. She sang along to all of the songs at the top of her voice, her very recognisable Brenda Lee tones echoing around the auditorium. She was a great dancer, too, and taught me all of the latest moves: the Mashed Potato, the Watusi, the Pony.

Brenda was booked to appear on one show alongside Gene Vincent, the rocker. He was so out of it, he pissed all over the floor in the corridor outside the dressing rooms.

Brenda was due on stage, so she opened her door. “Oh my God,” she said, looking at me. “What’s with all this water on the floor?”

I thought quickly. “It’s one of the fire extinguishers,” I explained. “I think it must have leaked.”

Brenda harrumphed and hitched up her voluminous skirt. “Well, somebody better get it cleaned up.” She tiptoed off to perform, unaware of what her beautiful shoes had just waded through.

But of all the American artists that I looked after in the early 1960s, I probably had most fun with the Ronettes. There was a period when Estelle Bennett was dating George Harrison, and a whole group of us would go dancing every night until the sun came up. We would go to discos or Dolly’s on Jermyn Street: a wonderful basement bar that would stay open all hours.

I’d got all my moves, which I had been taught by Brenda Lee, and would be up there with the girls. We got back to George and Ringo’s flat at six or seven in the morning. Around us, people were leaving their houses and going to work, while we were all smashed and giggling. In the flat, we pulled everything we could find out of the cupboards and cooked. I’d call it breakfast, but it was more of a drunken feast. Eggs, processed peas, everything. But we were so hungry that nobody minded – and we ate the lot.

By the late 1960s, I was working for George Martin, but I only went down to Abbey Road to see the Beatles record occasionally. If you’re not directly involved, studios are quite tedious places to be around – endless hanging about and testing the microphones. I always felt a bit like an intruder in someone else’s workplace. I did drop in for some of the Sgt Pepper sessions. I remember watching them record Lovely Rita. George Martin turned to me and asked if I could find him combs and some tissue paper – not always the easiest things to find in a recording studio – but I rustled some up, and you can hear the result in the final recording: that strange whoop, whoop noise in the background.

Around that time, I first met Elton John – or Reg, as he was then – at the office of Dick James, the Beatles’ publisher. He was fantastically shy back then, wouldn’t say boo to a goose. He didn’t seem at all like the person who would be charismatically wowing audiences in a few years’ time; he was kitted out in a jean jacket and jeans – double-denimed – if I remember correctly. The two of us couldn’t have looked more different. In his autobiography, Elton said that I could have drawn attention to myself even during a Martian invasion. I was certainly quite out there: as well as my love beads, I had a thing for antique silk scarves, velvet trousers and streaks in my hair. We immediately developed a firm friendship.

Then my whole world was turned on its head when I met Curt, a record producer from Sweden. It was a coup de foudre. He said: “I want you to come and live with me in Sweden.” He gave me a wedding ring. He had bought one for himself, too, and we had our signatures engraved on the inside of the bands.

The telegrams from Sweden continued. Then one day, they stopped.

I couldn’t work. I was so unhappy that I couldn’t concentrate. I had to go to George Martin and say: “I’m so sorry, I think I’m going to have to leave.” I left my job; I left London. All the fun and parties, I just wasn’t in the mood for any more.

When I was finally ready to come back, after a miserable winter, it took a while for a proper job to open up. To begin with, the only position I could find was answering the telephones at one of the large HMV record shops, which I had to take just to make ends meet. Elton John used to ring up and tease me. He’d put on a fake voice and ask me to run around the store and look for this or that record for him. It was only when I got back and heard him laughing that I’d realise who it was. “You bugger,” I’d growl down the phone at him.

Cut to 1973. Trying to reverse-park a Thunderbird is not the easiest manoeuvre at the best of times. But in a packed restaurant car park in Santa Monica, it felt more difficult than it should have done. That was down to my passenger, John Lennon, who was sniggering and chuckling at my attempts to squeeze the car into a space. Flustered at the fact I had got the angles all wrong again, I lined the car up once more and prepared to have another go.

Even though John couldn’t have been nicer that day, there was something about him being in the car that was intimidating. I knew how sharp-tongued he could be. It was a particularly hot LA day, and I could feel my hands starting to sweat against the steering wheel.

“What’s wrong?” John asked, laughing.

“What’s wrong,” I said, crunching through the gears, “is you being in the car with me.”

The more flustered I got, the funnier John found it. And the funnier John found it, the more flustered I became.

“Well, what are you going to suggest then?” John asked.

“I am going to suggest that you get out of the car, go into the restaurant and get the table in my name.”

John thought it was hilarious that I’d ordered him out of the car and made him go and wait in the restaurant. By the time I joined him and his girlfriend May Pang at the table, they were roaring with laughter. It might not sound like much, but from that moment of humour, we began to communicate properly. We were very close throughout the time that I worked for him. This was during his “Lost Weekend”, as he referred to the 18-month period during which he and Yoko were separated.

Although John was the special one of the Beatles, he had been the least successful since the band’s split in 1970. I think that was one of the reasons why he wanted me to work for him. He had a lawyer who handled the business side of things, but he needed a manager on the creative side, to steer him.

The first of John’s albums I worked on was 1973’s Mind Games. The campaign for it featured a somewhat unusual TV commercial. The idea came when singer-songwriter and musician Mike Hazlewood and I got stoned one night at his house in LA, and I began doing an impersonation of the Queen telling people to go and buy the album. John found the idea hysterical and wanted me to do it on TV.

It got more surreal when I realised I had to find a costume. I went down to Western Costume, a store used by Hollywood. “Which one of you is the Queen?” the woman behind the counter shouted. Everyone turned to look at me as I raised my hand. I must have annoyed the people queuing because I kept on rejecting the dresses they sent out for me to try on. “No,” I said, turning down yet another. “Her Majesty wouldn’t be seen dead in that.”

The ad recording took place at a studio in Santa Monica. Elton was in town, and I’d talked to John about him quite a lot. “You’d like him,” I’d said. It was quite a weird introduction, as Elton turned up in the middle of my getting changed. I stood there wearing a crown and make-up, but still in my jeans: “Elton, John… John, Elton.”

The advert itself opened with Land of Hope and Glory playing and a pair of doors opening to reveal me sat on the throne, sceptre in one hand and a copy of Mind Games in the other. You can hear John sniggering in the background.

John decided he wanted to follow up Mind Games with a rock ’n’ roll album and he wanted Phil Spector to produce it. The whole set-up felt borderline out of control; it was all too edgy. John was a little crazy. Phil was a little crazy. The studio was filled with drink and drugs and party guests and hangers-on. Warren Beatty, Joni Mitchell and many others would drop by and it all became quite raucous. On one occasion Phil pulled out a gun as a prank and fired it in the control room. Mike Hazlewood used to take a bottle of vodka to the sessions in his guitar case.

One morning, I was woken up at 3am. It was May Pang on the phone, and she sounded panicked. “You’ve got to come to the house,” she said. “There has been some trouble.” In the background I could hear shouting and the sound of something being smashed.

“What is that noise?” I asked.

“It’s John,” May said. “Please, Tony. Hurry.”

When I arrived, May looked as worried as she sounded. “Everything got crazy at the studio,” she explained. “Crazier than normal. Everyone had been drinking and doing God knows what. John was a mess, so Phil and his bodyguard brought him back to the house. They tied him up and left him there to calm down. Except John broke free and now he’s...”

Behind her, I could hear another smash. I could see a silhouette of John in the doorway, shouting. He was trying to pull a palm tree out of the ground, without much success. I could see that windows were smashed and, behind him, gold records had been pulled off the walls and scattered across the floor, where they lay twisted and bent. I didn’t even know you could do that to a gold record.

As I walked up, John clocked me. There was a wild look in his eyes. The only thing that I could think to say to him was: “What is the matter with you? What is going on?”

He broke down, fell on my shoulder and started sobbing. “They tied me up. They tied me up.”

He was clearly shaken. And not without reason. The Manson Family murders had taken place in LA only a few years earlier and were still in the back of everyone’s mind. I hugged him and said: “Come on. Let’s go inside and sit down.”

But drinkers who have blackouts can switch without much notice. One minute I was helping John in, the next he had turned on me and was starting to fight.

We collapsed on to the floor in a heap. For a moment we were rolling back and forth, until finally I was able to clamber on top of him. I lay there, pinning his arms down by his sides so that he couldn’t take a swing at me. Our faces were almost nose to nose.

As quickly as he went into it, John came out of the blackout again. His expression changed from anger to confusion to mirth.

“I never knew you were so strong, dear,” he said, and we both burst out laughing.

Later, to say thank you for sorting out the house, he gave me a picture of Marilyn Monroe by Andy Warhol. On the back was a handwritten note: “To Tony with love, from one of your problems, John.”

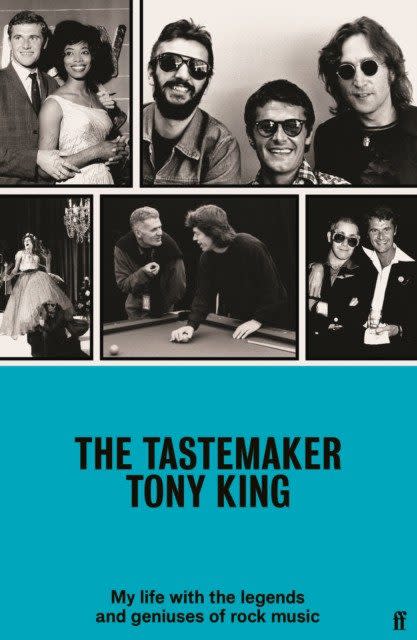

This is an edited extract from The Tastemaker by Tony King (Faber, £20), published on Feb 2