John DeWitt was eyewitness at deadly Washington scene

Canton native John DeWitt was an eyewitness to a tragic moment in American history a century ago.

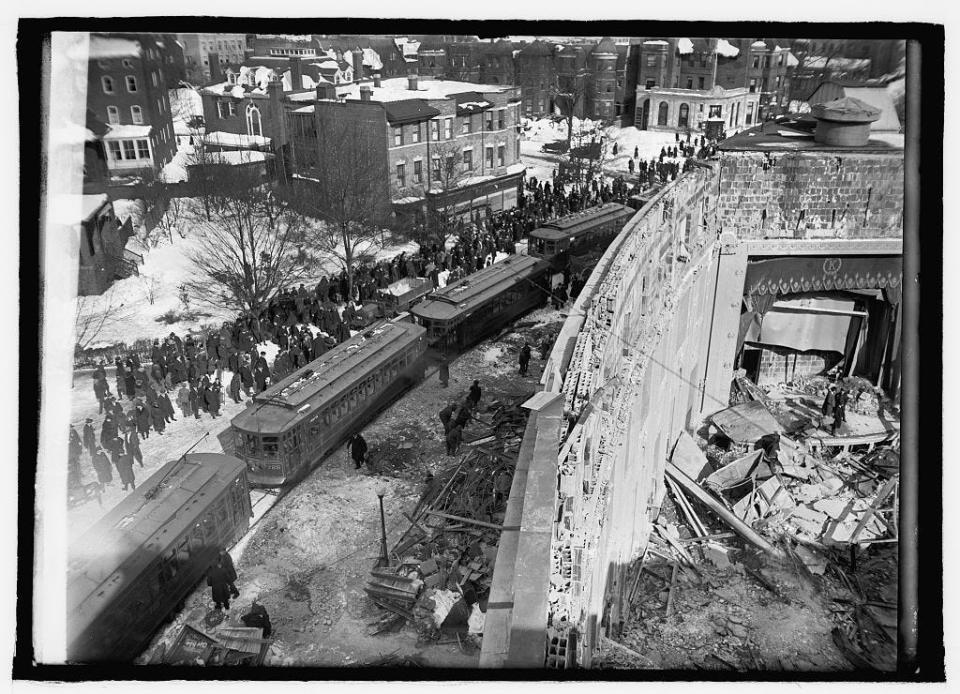

When the roof of the Knickerbocker Theater in Washington, D.C., collapsed Jan. 28, 1922, killing almost 100 people, DeWitt was one of the first responders on the scene.

DeWitt "aided in rescue work following the disaster," reported an article in The Canton Repository in the days following the deadly incident. The son of Dr. and Mrs. J. P. DeWitt, then of 815 Tuscarawas St. W, drove an ambulance for more than 12 hours after the roof fell on a theater filled with patrons.

More: Ohio played important role in history of Black baseball

More: Gary Brown: Recalling the words of John Madden

"I am well and safe after an exciting night," he wrote in a special delivery letter to his parents in the aftermath of his participation in the rescue work. He told them that he arrived at the scene shortly after the roof came down, taking the place of a regular ambulance driver who had broken his arm.

Even as DeWitt drove, he endured a sometimes sad result of his frantic rescue efforts.

Some 16 people died on the way to hospitals, a headline in the newspaper reported at one point in its coverage.

Still, the young man continued to rush others to the safety of hospitals and other emergency medical facilities, taking them to the saving care of medical professionals.

"A soldier and I hauled the injured through a 26-inch snow," DeWitt wrote, "from 9:30 in the evening of the catastrophe until 10:30 the next morning."

Many killed when theater roof falls

Bold and banner front-page headlines in the Repository on Sunday Jan. 29, brought the news of the disaster to the paper's readers.

"THEATER ROOF FALLS; MANY DEAD," the top headline shouted.

"Hundreds Buried In Wreckage As Snow Crushes Roof In Washington," another headline reported, followed by "Balcony Collapses, Concrete Pillars Fall Into Human Mass Of Injured And Dying.

"Scores Of Notables In Catastrophe In Fashionable Section — Heavy Snow Hampers Rescuers."

An Associated Press article published in the Repository reported the first news of victims, noting that early estimates of the number of people in the theater — "one of the finest motion picture houses in the city" — ranged from 150 to 500.

"The theater was said to be comfortably filled at the time and the roof as it fell imprisoned many under the mass of wreckage, the balcony collapsing also, while concrete pillars fell over to add their weight to the debris under which the wounded lay groaning," the article said.

"Many women who escaped ran screaming to the street and several fainted while the injured were removed on stretchers and taken in ambulances to hospitals, private homes and nearby clubs."

Death came to many theater-goers

The movie being shown that night was "Get Rich Quick Wallingford." Debris from the disaster didn't distinguished between the wealthy and the more common residents of Washington who were attending the film showing, the second of the evening.

Among the victims was Edward H. Shaughnessy of Chicago, second assistant postmaster general, who came to the theater with his wife and two children, who also were injured in the incident. Three days later, Shaughnessy was listed as being in serious condition, "with only a fighting chance for recovery."

Shaughnessy soon died at Walter Reed hospital from his injuries, the New York Times reported on Feb. 3, 1922.

Although the Washington coroner initially predicted that as many as 300 might have died in the disaster, and more than 100 people were reported by the Associated Press to be dead three days after the collapse, the death toll eventually was set at 98.

A massive effort was undertaken to save as many of those who were trapped in the theater debris.

"By midnight, 200 police officers, soldiers and firefighters were on the scene; by 6:30 a.m., their numbers had ballooned to 600," recalled a recent historical article published by Smithsonian Magazine, a story that looked back on how hundreds of onlookers also were drawn to the scene of the theater collapse, even though a large amount of snow that had blanketed Washington late in January 1922. "A fleet of ambulances from Walter Reed Army Medical Center helped evacuate the injured, and every hospital in the area was filled with Knickerbocker victims."

Canton man drove many medical care

In his letter, DeWitt told of the tragedy by describing the scene in a manner that was graphic and disturbing.

"They have found persons far below the surface and are feeding them through tubes," he wrote to his parents. "Hands and legs protrude everywhere. ...

"One poor chap has laid since last night with both legs crushed by a girder. His dead wife's body is pinned across his chest and neither can be removed without amputation of the man's legs," DeWitt wrote. "The dead are a common sight and are no longer a thing to be stared at. They have been regarded as 'things' for the last several hours."

Still, many who were alive were rescued and transported by individuals such as DeWitt to places where they could be treated for their injuries.

But, even those triage sites, guarded by Marines, became chaotic, Dewitt wrote in his letter.

"The friends and relatives of the members of the audience of the ill-fated show became frantic to the point of violence on several occasions. Our car was grasped and held by hundred of hands while the stretchers inside were scrutinized for identification. Some of our injured were brutally handled in this manner until we secured a Marine guard for the ambulance."

DeWitt himself sometimes was mistaken for a person in need of treatment by medical professionals.

"I was covered with blood before we had carted many victims," he explained in his letter. "It was with difficulty several times that I convinced the doctors that I was intact."

His obvious weariness compounded the misunderstandings as the hours elapsed.

"I am tired and sleepy," DeWitt admitted at the end of his letter. "For once in my life, I had enough excitement. Now I shall rest."

Reach Gary at gary.brown.rep@gmail.com.

On Twitter: @gbrownREP

This article originally appeared on The Repository: John DeWitt was eyewitness at Knickerbocker Theater collapse