Joe Biden Hasn’t Kept His Promise to Reduce the Prison Population

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For thousands of people in federal prisons and their loved ones, the last session of Congress ended on a heartbreaking note. Despite high hopes and bipartisan support for several sentencing bills, Congress failed to pass any meaningful reform during 2022.

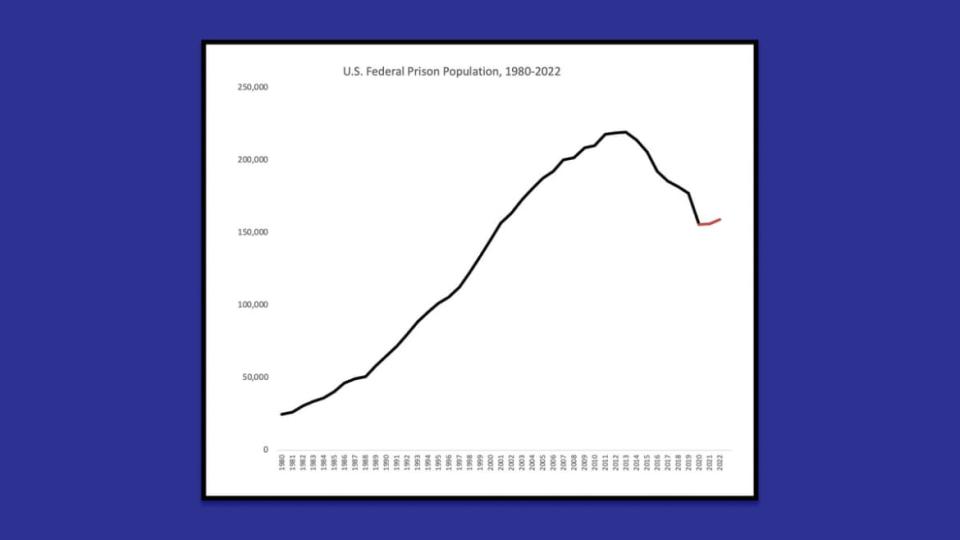

That repeated failure—coupled with the Bureau of Prisons’ refusal to make adequate use of compassionate release, and President Joe Biden’s limited use of executive clemency—has translated into the federal prison population increasing for the past two years (after nearly a decade in decline), despite the president’s promise to cut it by half.

This year, Congress must do better. It’s time to pass the EQUAL Act, the First Step Implementation Act, and the COVID-19 Safer Detention Act.

It’s Way Too Easy for Abusive Prison Guards to Get (and Keep) Their Jobs

We know firsthand the profound need for sentencing reform. One of us served 33 years of a life sentence in federal prison before receiving compassionate release. The other is a sentencing researcher who has documented the growth and harms of lengthy prison sentences. We’ve lived and studied the dramatic rise in the federal prison population and we know the urgency of finding solutions.

Federal prisons imprisoned 25,000 people in 1980. Today, they imprison more than six times that—nearly 160,000 people. (Fortunately, today’s count does represent a 27 percent reduction from 2013, when the population was at its peak of 219,000 people.)

The past decade of legislative reforms and policy changes, amplified during the early pandemic, have downsized federal prisons. But in the absence of new reforms by Congress and bold action by the administration, the federal prison population has grown again for the past two years.

The human toll of those failures is immense. Elderly people are growing frail in federal prisons, when they should be safely living out their final years at home with their loved ones. Children are growing up without parents who could have safely come home years ago. Scarce public tax dollars are being spent on prisons, instead of the interventions that actually make communities safer and save lives.

And all of those burdens disproportionately fall on Black, Brown, and poor people.

Meanwhile, extreme sentences are counterproductive to protecting public safety. Most people naturally age out of crime and by the time people are in their 50s and 60s, they pose a very low risk of committing a serious crime. Reducing excessive sentences can help us make much more effective investments in public safety.

That’s why Congress must act and leadership on both sides of the aisle must prioritize bipartisan reform.

The EQUAL Act would end the infamous disparity between sentences for crack and powder cocaine—a disparity that was born out of racism and hysteria in the 1980s.

Cops Love Immunity—Until They’re the Ones Abused by Police

Law enforcement, doctors, and criminologists agree: there’s no justification for punishing people convicted of crack offenses more harshly than people convicted of powder offenses. The bill already passed overwhelmingly in the House last session. While Attorney General Merrick Garland recently enacted a charging policy that will reduce disparities, this doesn’t help people already in prison, and is limited to the tenure of the Biden administration.

The First Step Implementation Act would make key provisions of the First Step Act retroactive. When it passed the First Step Act in 2018, Congress made clear that it considered some sentences too long and shortened them. It’s only fair that the people sentenced prior to this law should receive that relief as well. The bill would also allow courts to consider sentence reductions for people who committed crimes under the age of 18 and have served at least 20 years behind bars.

The First Step Act also currently includes a significant flaw. It arbitrarily excludes the oldest people in federal prisons—those convicted prior to November 1, 1987—from applying to courts for compassionate release. The COVID-19 Safer Detention Act would make them eligible, while also allowing elderly people who have served the majority of their sentence, and who the Bureau of Prisons deems low risk, to return to their families via the elderly home detention pilot program.

‘Riotsville, USA’ Shows the Birth of Police Militarization

Collectively, these three bipartisan bills could allow thousands, including the oldest and sickest people in federal prisons, to return home to loved ones and communities. They would also eliminate costly, pointless incarceration that keeps people from entering the workforce and supporting their families.

The path to bipartisan criminal justice reform isn’t easy, but it’s essential for justice and fairness. A Republican Congress during a Republican administration passed the First Step Act. This Congress has the capacity to pass meaningful reform, too.

As Sens. Dick Durbin and Lindsey Graham and Reps. Jim Jordan and Jerry Nadler set Judiciary Committee priorities this session, sentencing reform must be at the top. And President Biden should lead the way by recommitting to his campaign promises of dramatically decreasing the federal prison population.

Nazgol Ghandnoosh is Co-Director of Research and Bill Underwood is Senior Fellow on the Campaign to End Life Imprisonment at The Sentencing Project.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.