Jim Carrey Would Like to Be Erased Forever

“When the individual has no belief in his own act and no ultimate concern with the beliefs of his audience, we may call him cynical . . . the cynic, with all his professional disinvolvement, may obtain unprofessional pleasures from his masquerade, experiencing a kind of gleeful spiritual aggression from the fact that he can toy at will with something his audience must take seriously.”

~ Erving Goffman, The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life

IT'S WINTER 2010 and Jim Carrey has once again walked through the door, “Truman style.” Walking through the door—the metaphor taken from Carrey’s role as the Truman Show’s titular movie star (Carrey, the movie star within the movie), which became a prophetic part both for Hollywood culture and for Carrey himself—walking through the door—happens every so often. It has become the life-imitating-art way for Carrey to express escape. From fame. From expectation. From having to play himself. Like most pathways to enlightenment, the threshold crossing can be painful; walking through the door at times means sweet euphoria and, at times, supreme hell.

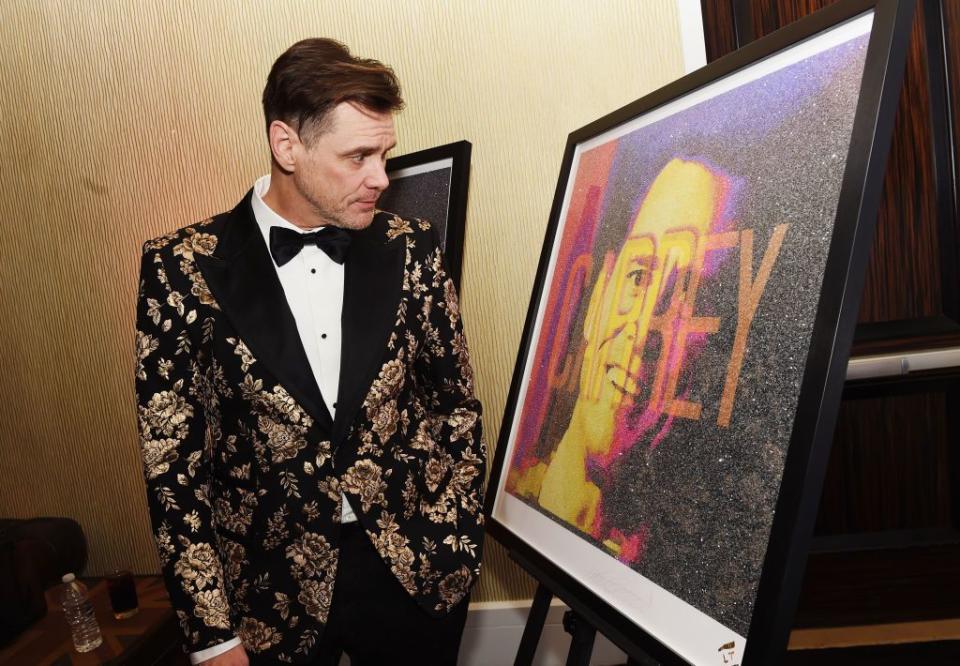

So Jim Carrey is through the door once again, and, now on the other side, dragging large paint cans down the cold streets of the West Village. He’s set up an art studio here. He spends all day painting and parts of the early morning “dispatching drunks” and most hours heartbroken. He’s battled depression his whole life, was on Prozac for a time, and had since switched to a regimen of part cognitive behavioral therapy and part holistic medication—hydroxytryptophan and tyrosine, just enough to bump his dopamine—and now part painting, which is doing wonders for Carrey, because “creativity is medicine.”

Word has gone around town that Carrey is painting. Word is: Carrey’s looking for a writer to help pen an essay about his paintings—what they all mean, this hellacious euphoria put to canvas.

Across town in Park Slope, writer Dana Vachon decides to take full advantage of the offer and go say “hi.” He has absolutely no interest in authoring Jim Carrey’s art manifesto; he just wants to meet the comedian. They swap numbers.

Not long after, Carrey texts: “Hey man, what are you doing?”

Vachon is back at his apartment, stealing Wi-Fi from his neighbor and fully expecting never to talk to Carrey ever again. (Carrey, now, years later: “He had no idea how badly I needed a friend.”)

Vachon: “I dunno, what are you doing?”

Carrey: “Watching Netflix.”

Vachon: “What are you watching?”

Carrey: “John Barrymore in Jekyll and Hyde.”

And then, all of a sudden, the two are on a phone call, both watching the 1920 horror flick together, riffing.

And then Jim Carrey, step by step, begins breaking down the facial performance of John Barrymore: “Now watch here. Barrymore knows he needs to do these things with his face. So there’s an economy that he’s . . .”

And then, for whatever reason—maybe it’s their shared late-night, cable-surfing insomnia, or how they’d both known extreme highs and lows in life, or how they’d both been at one point disgusted by the façade of their industries (Vachon began as a Wall Street analyst)—this kind of conversation continues. For years.

And then one day, something comes to Vachon, an opening to a story, Jim Carrey's story. The two had been discussing writing Carrey’s biography together. But neither of them had wanted to write some boring memoir, because do you ever really know someone after reading their memoir? (And can you ever really know anyone anyway?) Carrey didn’t think so. Carrey wanted to create.

Vachon calls Carrey now.

Vachon: “Hey, I’ve got this scene. There’s this guy. His name’s Jim Carrey. And he’s in his house. And he spends like, a lot of time there. And you wouldn’t expect it, but he’s just mainlining content.”

There’s a long pause. Vachon is terrified. Carrey is about to tell him it’s a horrible idea, he thinks.

Carrey, finally: “… And you know what else? Sometimes Jim Carrey makes himself up before he goes to bed, because he’s afraid of selfies that will be taken at the morgue, if he dies in his sleep.”

And that’s it—the book is born. It begins with that scene and then it explodes: deepfake Jim Carrey pornography, Chinese conspiracies, backyard epiphanies, aliens. Carrey and Vachon can’t stop themselves.

Is it true? Did these things really happen to a man named Jim Carrey? It doesn’t matter. They feel true. They feel truer than any celebrity memoir. For Jim Carrey, it feels like the truest version of himself he’s ever created.

Do you know Jim Carrey? The real Jim Carrey? Jim. Jimmy. Jimbo. The Jimster.

You’ve certainly seen the Jims.

You’ve seen the fun, farting Jim Carrey, the goofball. The physical comedian. The 1994 Jim Carrey, star of that breakout year when Ace Ventura and The Mask and Dumb and Dumber all pushed his salary to $10 million per film (and then not long after, $20 million), when he was getting compared to Buster Keaton and Jerry Lewis and the head of Columbia Pictures said he may be the biggest star in the world. Well, for a time, maybe until the mid 2000s, Carrey probably was the biggest star in the world.

And then there was a gap—maybe ten years—in which you probably forgot Jim Carrey existed.

And then he resurfaced, and you probably read about the new Jim Carreys, the bizarre, the provocative, the wait-is-that-really-Jim-Carrey Jim Carreys. Maybe you read about how he became a painter and a political cartoonist. How he began painting multi-ethnic Jesus (“Christ consciousness”) and then Trump. Or how he nearly lost his mind filming Man on the Moon, and, how, a few years ago, after that documentary about how he nearly lost his mind filming Man on the Moon, he grew out a beard and began going on talk shows and saying things like: “I used to be a guy who was experiencing the world, and now I feel like the world and the universe experiencing a guy.” Or, during that uncomfortable fashion show interview: “I didn’t get dressed up. There is no me.”

You probably thought Jim Carrey just went crazy.

But the truth is stranger and more wonderful still.

For eight years, they talk. Talking and writing is medicine, salvation. And Jim Carrey tells Dana Vachon about … everything. Everything it has ever meant to be Jim Carrey. All the Jim Carreys. The child Jim Carrey making faces in his bedroom mirror. The teenage Jim Carrey, the high school dropout, driving with his dad hundreds of miles through the snow to perform standup. The Jim Carrey making his big break, opening for the legend, Rodney Dangerfield, booking The Tonight Show, getting his first TV role. The 1994 Jim Carrey. And then the Jim Carrey that remained when the mega star Jim Carrey began to fade.

And with all these Jim Carreys assembled, the two friends begin crafting the next Jim Carrey, the Jim Carrey to contain all Jim Carreys. A Jim Carrey different from the Jim Carreys of past writers and journalists, those people who believe after an hour or so with a “subject,” they can somehow capture that person, read his inner most self in everything he does: in the way he responds to a fan, or drinks a Diet Coke, or swings a golf club. No, you just get more Jim Carreys. The Rolling Stone Jim Carrey or the Esquire Jim Carrey or the TMZ Jim Carrey. And can you actually call those real?

No. But while helping write this new Jim Carrey, the Jim Carrey who battles aliens with Gwyneth Paltrow and isn’t real, something really weird starts to happen: Dana Vachon begins to see the Jim Carrey everybody else kinda missed.

One day, while the two are writing an absurdist scene fixated on Carrey’s father’s bowtie, Carrey leaves the room and Vachon, still writing, looks up to see Carrey standing there holding the actual bow tie, like a relic. On another occasion, working on a hallucinogenic dialogue with his father—his father being ground to death in a Play-Doh Fun Factory belt—Carrey writes the line, “I started dreaming for you,” and Vachon thinks, hell, here in the craziest, most unreal scene was the truth of a father son relationship: I started dreaming for you.

Carrey’s father died in that breakout year, 1994. He never saw Carrey become a mega star. If there’s one thread that ties together all the Jim Carreys, it is he, Percy Carrey, Jim’s father. How his father reminded him of a real-life cartoon. How his father had given up musician dreams, artist dreams, to raise a family and see his son through the snow to his comedy gigs, his son’s art. I started dreaming for you.

A truth. Did Vachon stumble upon ... a truth? And does Danna Vachon know Jim Carrey now? The ur-Jim-Carrey, the true Jim Carrey?

Well, if you ask Jim Carrey who Jim Carrey really is, he will probably tell you that Jim Carrey is, in fact, no one. Jim Carrey doesn’t exist. And doesn’t that make a purposefully fictional Jim Carry who doesn’t exist just about the most real Jim Carrey of them all?

If Jim Carrey didn’t go crazy, then what the heck actually happened?

The answer is that sometime around 2000, Jim Carrey began to see. He began to see the charade of persona—the Latin origins meaning something like: a theatrical mask. Like Carrey's own film, The Mask: it’s something you wear, something that alters you and also becomes you, but falsely.

And the true story of Carrey’s not-crazy path to enlightenment begins in Toronto. Carrey started, in his teenage years, as an impressionist. He did Elvis and Henry Fonda and Ghandi and dozens more. Then one day, he wanted to be original. So he dropped the impressions and took the stage each night simply as Jim Carrey—with nothing prepared. He would just improvise on the spot. Some nights he got killed—yelling, bottles thrown. Some nights he did the killing—and the throwing. He was becoming someone new each time, some new Jim Carrey.

But who did Jim Carrey want to be? Who could he be? He was still so young.

So young that when Rodney Dangerfield first spoke to Carrey in his dressing room, he just looked down at the young comedian and, without saying a word, began howling uncontrollably with laughter.

He turned to his friend, Joe Ancis, and said: “Who the FUCK is this guy, man?? Look at him!”

Then to Carrey: “Have you ever been in LOVE??”

He had not. But what Carrey could be was the audience’s release valve. He could be unbridled joy. He could be a man Free from Concern, so that his audience would be free from concern. That would be his persona, his main mask, he decided.

Erving Goffman, the Canadian sociologist, wrote of social behavior as mask wearing. When we dine with friends, when we meet strangers, when we interview for jobs, we, like thespians, are wearing faces. We do this unconsciously—and mostly to blend in. But there is one person among us who wears his mask differently, consciously, intentionally. Goffman called this wearer “cynical.” “A cynical individual may delude his audience for what he considers to be their own good, or for the good of the community.” Elsewhere, Goffman refers to one cynical act as a “pious fraud”—a kind of innocent deceit.

For years, the Man Free from Concern was Carrey’s fraud. He laughed and farted and climbed up walls and lived knowingly, willingly, inside Hollywood’s Truman Show—all to make his audience roar. But a time came when Jim Carrey no longer wanted to be that man, when the jester’s face became too heavy and he took that mask off.

That’s what his novel with Dana Vachon comes to be about. It’s about dismantling “Persona.” It’s about the persona of “Jim Carrey,” someone who tried so hard for so long to be one thing, but realized, later, he was no longer doing it for an audience, but for himself. His mask, his Ego, demanded relevance and so he was performing for it, for himself. He was committing self-fraud.

So he threw the mask of Jim Carrey away, and he began a new, better, more cynical act: a war on Jim Carrey, a fraud to reveal fraudulence.

You see, for the last two decades, Jim Carrey has been on a singular quest to reveal and then vanquish Ego. To tear off its face, to stretch it and show that face as a false idol. And then to paint on it several contradictory faces that are somehow all true and false—and then to wear it.

What happened when Jim Carrey set forth on this quest? Well, the world couldn’t see what Jim Carrey was doing. What he was doing with those weird red-carpet interviews and bizarre late-night ramblings: he was showing the audience their own masks. They didn’t understand.

And what happened after he did these things? The world simply had enough of Jim Carrey. They started writing things like “Why won’t Jim Carrey just shut up?” and “Hollywood won’t cast Jim Carrey anymore.” He had all these colors to paint with now—humor and heartbreak and self-awareness. (That’s what Dangerfield meant when he laughed: there was a world of emotions left to be had and with them you construct art and with art you get to be free and not burdened by Self. With art you get to teach others about the burden of Self.)

Yes, he had all these colors now, and he walked through that door on a quest to vanquish self, and he dragged paint cans down the streets of the West Village, and all the while we thought he was just losing his mind, losing his relevance. But it was the opposite. OH BOY! was Jim Carrey on to something this time.

Jim Carrey is sitting in his L.A. kitchen with Dana Vachon a month before publication. They’re doing a Zoom interview about their novel and looking like two brothers who can’t seem to sit still at the dinner table. They wear the same devilish grin.

They talk about meeting each other and becoming fast friends and how they didn’t mean anything by turning Gwyneth Paltrow into a militant alien killer, because Jim Carrey actually really respects Gwyneth Paltrow, and also “we plugged Goop, so what do you want??”

And then there comes the question, the question no one really knows the answer to anymore, because they stopped asking: who is Jim Carrey now—all these years later?

Carrey becomes serious. “I’m two things,” he says. “I’m a body and mind that has to defend itself and take care of itself and try to make a good show of itself in the world.” (The original fraud.) And then Jim Carrey is the other thing, which contains the first: he is everything. “There is nothing that isn’t me,” he says. And this everything is why he, Jim Carrey, doesn’t really exist. Because how can you exist, when you are the same as all things?

And then Jim Carrey tells the story of the first time he walked through this door, Truman style. The moment when Jim Carrey didn’t want to be Jim Carrey anymore and his new beautiful fraud truly began. It's a story best told last. Would you believe it if told first?

It begins one night in 1999.

“In a very desperate moment in my life, I was driving up the Pacific Coast Highway in a convertible in December, and it was cold and I had tears pouring down my face, trying to figure out what the hell this whole mess is all about,” Carrey begins. He was brokenhearted then. No bags. Hell bent on San Francisco. Wanting to just check into a random hotel. “Then I thought: What are you doing? People know you. You can't just, desperately check in with no bags and looking like a maniac.”

Carrey decided to turn around. When he turned onto the on-ramp back to L.A., he thought about his recent roles as Andy Kaufman and Tony Clifton in Man on the Moon. He had disappeared behind those masks, and for the first time in a long time, he was free of Jim Carrey. He realized he was free only when he was someone else. And then Jim Carrey thought: what if I am someone else? “And this feeling came over me,” Carrey remembers. “Every bit of concern that I had in my body drained out of me. And suddenly everything was crystal clear. The moon, it was like I could reach up and pull it out of the sky. And I started laughing hysterically. I'm driving in the cold, and I'm laughing hysterically, and I’m crying at the same time with laughter, and my mind just started writing jokes, one after the another—jokes, jokes, jokes, jokes—to make myself laugh. I was free. I was totally free.”

The experience lasted for three days. And then the world returned—emails and calls from agents and, just, life. But Carrey glimpsed enlightenment: wholeness. And for the rest of his career, through art, he has wanted to convey this truth. But only if we can sift through the fraud. The fraud is for our own good.

“You must read beneath the words,” Carrey concludes. “Because [the novel] is really close to the bone. There are things here that are the source of terrible pain and the source of terrible challenge in my life. They’re all there in one form or another. It just might not be the exact details. But if you open up to reading a little deeper, you’re gonna know me.”

So maybe, in the end, we can know Jim Carrey. He's just, well, a little different, and maybe he isn't even Jim Carrey anymore. That's the strange and wonderful truth. As to which parts are true truth, which parts are personas and which parts are crying in convertibles—people will want to know.

Carrey just grins.

“That’s their problem,” he says.

And then, loudly, in a different voice and maybe a different Jim: “IT’S THEIR PROBLEM, MAAAAAAN!!”

You Might Also Like