How Jenny Slate Found Her Voice in a Tiny Seashell

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

About a minute into our Zoom call, it becomes apparent that Jenny Slate doesn’t do small talk. Not in the “I don’t do small talk,” performatively Authentic™ kind of way. But more in the sense that, when I ask how her day has been, she needs to contextualize her response by calculating where the current moment falls in her daily routine. She starts with bedtime at 8:30 p.m.–which she clarifies is indeed the bedtime of her and her husband of six months, Ben Shattuck, and not their 17-month-old daughter, Ida. Ida goes to bed at 7. Slate continues subtracting backward from their curfew. Bath time and singing around 6, dinner prep starts around 3:30 or 4…

“And you're free to put this is in,” she eventually quips, breaking the fourth wall of our article-in-progress. “I only have scheduling to offer.”

It’s not that Slate is on any kind of intense time crunch between press junkets (which, she does add, make her feel like a less famous version of Julia Roberts’s character in Notting Hill). It’s just that, well, she really has this schedule down. And she’s excited about that.

It's now 8 p.m. and as the 40-year-old's internal sundial guides her to open a beer on her couch, Shattuck is silently adjusting her lighting for her in the background like a sweet stagehand. There’s a distinct gentleness to her demeanor. It’s a disposition that has guided the comedian, actress, writer, and producer throughout her career–but it feels especially poignant as she now sits on the other side of her latest project, Marcel the Shell with Shoes On.

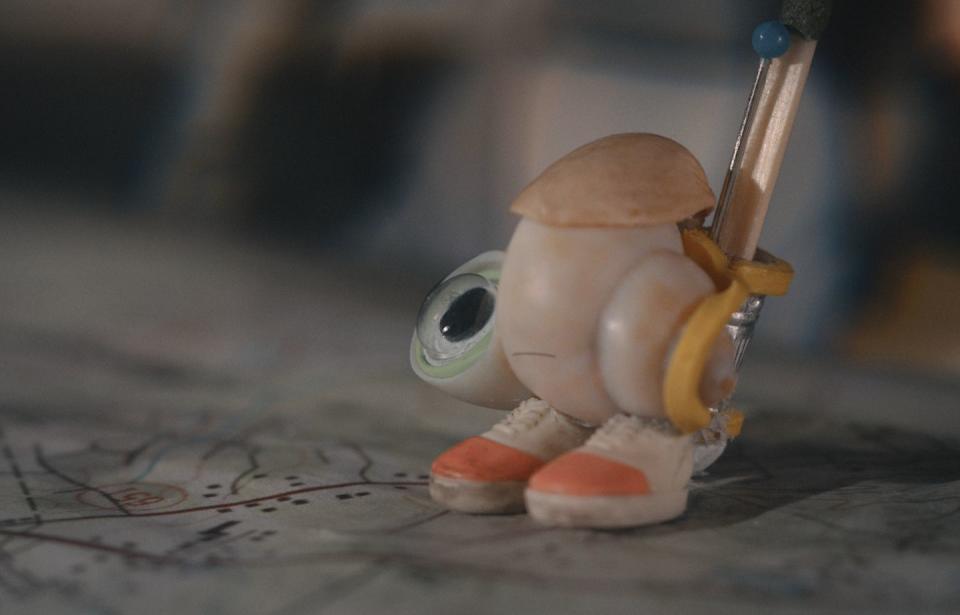

Out now in New York and Los Angeles, and releasing to theaters nationwide on July 15, Marcel the Shell with Shoes On offers something of a prequel and sequel to Slate and then-husband Dean Fleischer-Camp’s viral 2010 short film of the same name. The new work is shot in cinema-verité style, following fictional documentarian Dean (Fleischer-Camp) as he captures the life of Marcel and his grandmother, Nana Connie (Isabella Rosselini), after a mysterious exodus leaves them estranged from their shell community. When Marcel becomes an Internet sensation, though, his mission to reconnect with his family gains a new momentum.

The film is a labor of love in its truest form–which feels appropriate for a character whose daily life requires constant legwork. (Marcel literally steps in honey to scale along the walls of his human-sized home.) The film underwent a seven-year production process—beginning as an independent project, with the duo taking hours-long improvised audio recordings that would eventually inspire the treatment and stop-motion animation process. (Oh, along the way–Isabella Rosselini and Lesley Stahl joined the cast before distribution giant A24 picked it up.)

For Slate, Marcel the Shell with Shoes On is a homecoming to the character and project where she first discovered her voice.

When Slate first discovered Marcel in the depths of her vocal register, she was, quite appropriately, cramped within the confines of a cluttered motel room. Attending a wedding with Fleischer-Camp and three friends, Slate quickly became hyper-aware of her status as the only woman–and, more importantly, only tidy person–in their shared habitat.

“I started to sort of gently give a good-natured ribbing to the people I was staying with to tell them that they were messy and that I felt really tiny and, like, taken over,” Slate recalls. “So, I started to do this voice I hadn't ever done before. And I was fascinated by its tone, and by how satisfying it was to do it, and by how I knew just how to do it.”

At the time, Slate was freshly reeling from her first, and last, year on SNL. Up until that point, she describes her comedic style as “really just trying to be the most attention-grabbing.” “That was the way that it had been modeled for me,” Slate says, pointing to fellow show-alumni like Chris Farley and Kristin Wiig as examples. “And I think I was coming from a place of feeling like I had failed in that zone.”

No matter how much space Slate tried to take up, she couldn’t quite find a place where she fit. After white-knuckling her coveted seat as a cast member all season, she was fired from the show and forced to reckon with her artistic identity. “I had just been looking at myself and looking at myself and trying to figure out what was wrong for so long,” Slate says. But, with Marcel, she didn’t have to look at herself. In fact, she didn’t even “have to have a body at all.” With this liberation, Slate’s entire world seemed to open up inside of a one-inch tall seashell.

“I was like, ‘I just wanna do a gentler thing,” Slate recalls, “‘Like, I actually think something can be funny if it also is fairly melancholy.’”

This epiphany, according to Slate, informed everything for her–from the standup stylings of her haunted Netflix special Stage Fright, to her 2019 book of essays and poems titled Little Weirds. And, of course, how she would approach the role of Marcel in his subsequent shorts, children’s books, and feature film.

Slate compares her discovery of Marcel to “when you finally find something like a coat or a pair of pants. And you're like, ‘I finally get what my style is.’” As for Marcel’s literal style, Fleischer-Camp would be the one to quickly outfit his prototype from found objects in their apartment and at the local Brooklyn toy store. Slate first encountered the Polly Pocket sneaker-wearing seashell on her kitchen counter when she arrived home. “I just was like, ‘Oh, my god that’s it … That's definitely the guy.’”

Repurposing the character for a last-minute video he’d promised to make for a friend’s comedy show, Fleischer-Camp recorded an improvised interview with Slate. “I just improvised the first line, like, ‘My name is Marcel and I'm partially a shell, as you can see on my body.’ And it just kind of came out that way.”

Not long after Marcel’s, and, in turn, Slate’s, introduction to the Internet, the duo were welcomed with open arms. The seminal short, in which Marcel demonstrates a day in the life with short vignettes and one-liners, now boasts a view count of over 32 million.

“On the one hand, it was just sort of an affirmation that I really needed at the time,” Slate recalls, “that I can do something and be successful and have that thing that I do be something that I actually like.”

To finally shout your true voice into the void that is the Internet, and hear it echoed back with adoration, is surely a confirmation that you’ve found the right place in some ways. But, as for the setting itself, Slate didn’t exactly find herself at home. “I’ve neverrr … super related to the Internet,” she laughs. “I’m old enough to remember when it didn't exist, and to miss how it feels to present yourself to a specific person on purpose, hoping that they will understand you, rather than just kind of blasting an edited image of yourself into the world at large,” Slate explains.

There was a point in which Slate says she did enjoy platforms like Instagram and Twitter. But, as she says, “I got to a point of not necessarily being disappointed with the people online, but being disappointed with myself.” Slate says she’d never heard the term “thirsty,” but the shoe fit painfully well. “I suddenly was like, ‘Oh shit. I don't like how I'm acting,’” she says, “I suddenly saw such a magnification of my own loneliness.”

Slate has resolved that she is just simply not someone cut out for a life online. “Some people, it is really good for them and some people can handle it. There’s also people that climb Mount Everest and people that, like, fix people's heart valves for a living,” she laughs, “I’m just not a very extreme person in that way. I actually just love an interpersonal eye contact moment.”

Slate’s complicated relationship with social media is closely mirrored in Marcel’s journey, as his first encounter with the web coincides with his climb to viral fame.

There’s a running dynamic of reframing throughout the film, given Marcel’s scale and experience. Tennis balls are cars; inhalers are slides; and macaroni shells are trumpets. But, few aspects of daily life feel as unique through Marcel’s eyes as the Internet.

Unfamiliar to the world outside of his house, Nana Connie, and his shell community, Marcel’s first exposure to the greater world around him is nothing short of inspiring. After scrolling through thousands of adoring comments (which he does by scuffing one of his shoes across the mouse pad like a skateboarder), Marcel feels a renewed sense of abundance in life. “There must be so many others like me,” he says in awe.

But his seemingly-endless network of connection quickly proves to be disillusioning when he enlists the help of his thousands of fans to help in finding his family. “There’s so much nothing,” he says while reading endless meaningless comments on his videos. One comment, signed “peace and love” especially sets him off–which Slate admits was actually just a rant of her own caught on tape. “When we would record Marcel, I'd just kinda stay in the voice all day long for the most part.”

Slate says that, though extreme, Marcel’s arc is not unlike most humans. “When the Internet lets you down, you feel truly dumped, you know?” she says, “You realize how much you were pinning your hopes on this thing that doesn't even really have a shape.”

It’s also, of course, not unlike the experience of many performers in the digital age. “If you’re going from showing your personality to actually needing something, there’s just gonna be a lot of people who don't understand how to give that to you,” Slate explains, “because that's not how you've primed them.”

A film that features ziplining inside of a shoe and ice-skating across glass counters could easily pass for a thrill ride on its surface, but at the heart of Marcel the Shell with Shoes On is this act of gifting oneself to the audience. And Slate’s vulnerability is clearly matched by all of her co-collaborators–as Fleischer-Camp, co-writer, Nick Paley, and Kristen Lepore’s animation team leave their own fingerprints on the film.

Remnants of Slate and Fleischer-Camp’s own relationship even seem to be imprinted into the film’s DNA, as romantic relationships in the human realm play a ruling force in Marcel’s world. Fleischer-Camp recently told CBS Sunday Morning that his character, who is revealed to be nursing a romantic wound through the documentary project, is “a version of myself that doesn’t exist anymore.” Slate is also quick to point out which parts of Marcel's psyche were passed down from her or Fleischer-Camp.

Despite their divorce in 2012, Slate and Fleischer-Camp’s creative partnership is clearly driven by a deep, mutual admiration for one another–as exemplified by Slate’s total trust in Fleischer-Camp’s direction of the film. “Dean just has such beautiful taste. He's so brilliant,” she says, “He's really, really smart, but he's also really, really funny. And it all shines [in the film].”

The role of Nana Connie is also sourced from this ethos of personal gift-giving. An amalgamation of Slate, Fleischer-Camp, and Paley’s own grandmothers, Slate says that “because we all had so many grandparents in mind, I don't think we knew who [Nana Connie] would be.”

There was, according to Slate, essentially a list of “actors of a certain age” before Isabella Rosselini’s casting as Nana Connie. “When they said that Isabella was interested, we all weren't sure that we heard that correctly,” she laughs. Marcel’s relationship with Nana Connie is a driving dynamic in the plot, as the two navigate their post-family world together with a deeply intimate companionship. And, when Rosselini jumped onto the project, Slate says she “just wanted to work.”

Some of the duo’s scenes together were even recorded on Rosselini’s farm in upstate New York–offering a high-fidelity soundstage for field recordings of Nana Connie’s garden. As for jumping into improvising with Hollywood royalty as your scene partner, Slate admits she felt pretty shy at first–which, in true Slate fashion, she clarifies is “a really nice feeling.”

“It’s different than feeling fear. Like, when I feel shy, I just feel like, ‘I'm just staying in a shell,’” she says, hiding in her hands, “But it's not because of dislike. It's just the specialness of the situation feels like it's like laying on top of me and I have to, like, emerge from it.”

As Slate poetically pinpoints the human experience in her own way, it’s easy to identify the source of Marcel’s many musings–like how much easier it is to fall asleep when there’s a party going on downstairs. “I remember crying so hard while we were recording that,” Slate says. “That's how I always used to feel like at Passover Seders.”

Despite her love for her 8:30 curfew, Slate recalls in this moment how “impossible” it was to fall asleep the week prior while Shattuck was on tour for his latest book, Six Walks. “I've always had a real need for somebody else." Learning to be alone, she says, is an important lesson that she and Marcel have both had to learn. And yet, however lonely the world may seem at times, it feels much easier to rest knowing that voices like Slate, Fleischer-Camp, and, of course, Marcel the Shell, are out there in the chatter.

You Might Also Like