'Jeen-Yuhs' Is A Remarkable Chronicle of The Making of a Major Artist

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s February 11, 2016, and Kanye West is hosting a combination fashion show (for his Yeezy clothing line) and listening party (for his new album The Life of Pablo) at Madison Square Garden. At one point, he stands at the soundboard on the arena’s floor and recites rhymes from the new song “I Love Kanye:”

I hate the new Kanye, the bad mood Kanye

The always rude Kanye, spaz in the news Kanye

I miss the sweet Kanye, chop up the beats Kanye

I gotta say at that time I'd like to meet Kanye

See I invented Kanye, it wasn't any Kanyes

And now I look and look around and there's so many Kanyes

By that time, West had become one of the most polarizing figures in music—really, in our entire culture. He was among the most successful and most influential hip-hop artists of all time, but if you were paying any attention at all, you also had opinions about his toxic narcissism, boundless ambition, and erratic behavior. Even President Obama called him a “jackass.” A towering figure in 21st century music and a global fashion influencer, he could be simultaneously inspiring and infuriating, eventually insufferable. As the lines above reveal, though, none of this was news to the man himself. So many Kanyes, indeed.

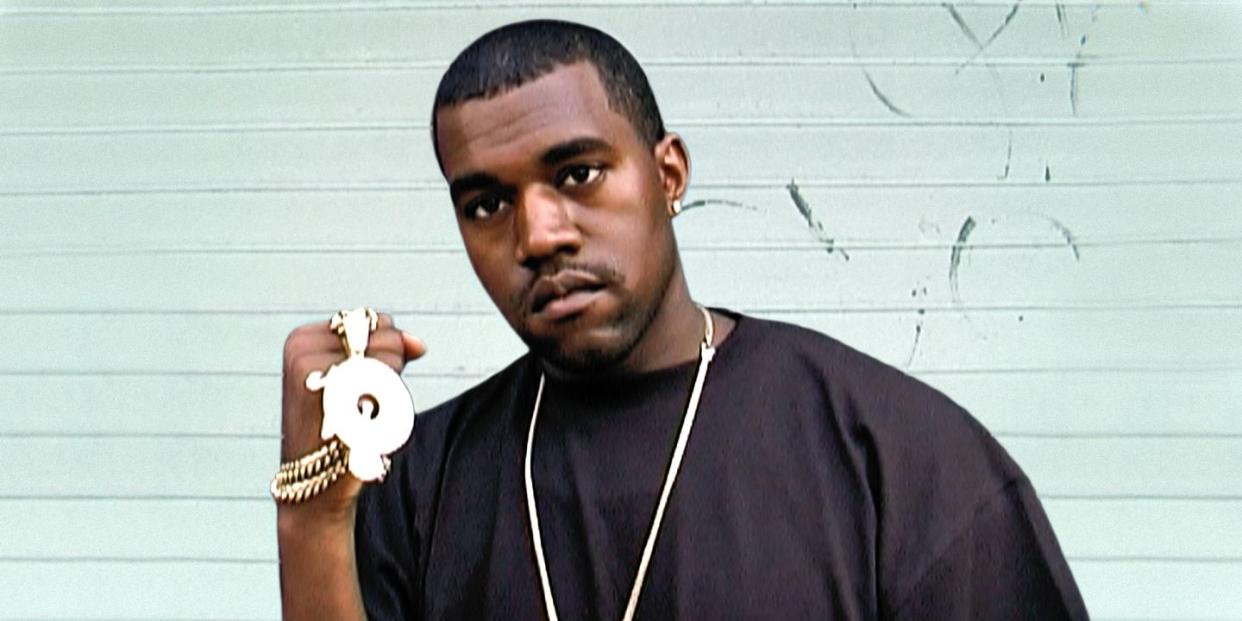

In the new, three-part, four-and-a-half hour Netflix docuseries jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy, we see West rapping that verse from just a few inches away, captured by the filmmaking team of Coodie and Chike. Coodie Simmons was a stand-up comedian and host of a local public access show in Chicago who met up-and-coming producer West in 1998 and, inspired by the groundbreaking 1994 documentary Hoop Dreams, decided to start filming him and see where things went.

It was a once-in-a-generation winning bet, though no one on earth would have anticipated that the project would last almost 25 years, nor the directions that it would go: In the scene from 2020 that opens the film, West is on the phone indicating that he has two priorities at the moment—his campaign for the United States presidency (“full steam ahead on that”) and getting the contracts done for this documentary. The incredible trove of footage accrued over the years is riveting and revelatory, even if ultimately there are parts of Kanye West that remain a bewildering mystery.

The first two parts of the film (Act 1: Vision, now streaming, and Act 2: Purpose, out February 23) are a remarkable, possibly unprecedented chronicle of the making of a major artist; they should be of interest to anyone interested in the creative mind, whether you care about hip-hop or music or not. In some ways, these episodes recall Martin Scorsese’s Bob Dylan documentary No Direction Home, or even Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids, model depictions of the pieces that help form a visionary creator—except that much of those stories is told in retrospect, while jeen-yuhs unfolds entirely in real time. In fact, the absence of analysis or critical context even risks underplaying West’s impact on music, from pioneering the use of sped-up soul samples and using autotune as a melodic device to fusing underground hip-hop rhyme skills with wide-screen braggadocio, offering a vulnerability that led to a generation of “emo rappers.”

West gets his big break soon after Coodie begins filming, when he starts producing artists on Jay-Z’s Roc-a-Fella Records, and his reputation explodes following his work on Jay’s 2001 classic The Blueprint. West doesn’t want to just be a beat-maker, though, he wants to be an artist himself—but he can’t get anyone to take him seriously, and we see him rolling into the Roc-a-Fella offices and rhyming for any employee he can find, even as one after the other is bored or visibly annoyed by the interruption.

West returns to his hometown for a conference, only to find himself the subject of a dis track by a fellow Chicago rapper. He seeks solace from the one person who offers unconditional support and belief in his vision: his mother, Donda, who tells him that he can sometimes “come off a little arrogant even though you’re humble.” Later, Coodie will note, in his laconic narration, that her honesty and her confidence brought out the best in West—that “the bigger he got, the more he wanted her around.” Eventually, he catches a break with an MTV feature (which is where the team meets Chike Ozah and brings him into the project), and Act 1 ends with West finally signing a deal with Roc-a-Fella.

Act 2 is almost completely dedicated to the making of West’s 2004 game-changing debut album, The College Dropout. Momentum is building, especially after he talks his way onto a feature on a Jay-Z track, when he crashes his car in Los Angeles and breaks his jaw in three places. The label is wary and takes his project off their release schedule, while he goes through multiple surgeries (Coodie films all of it, so trigger warning for the dentist-phobic). West begs and borrows studio time, and the experience inspires his breakthrough single “Through the Wire”: the episode concludes with his exuberant Grammy speech after he wins in the “Best Rap Album” category.

It's a moment of genuine triumph, the pay-off for West’s laser focus and unswerving confidence. But it’s also clear that after this level of victory, it’s only going to get harder for anyone to tell Kanye West what he can and can’t do. And as his career starts to take off, West begins to distance himself from Coodie, and the film grows increasingly scattershot. For the first time, he goes on tour without the documentary team.

That uncertainty is where Act 3: Awakening (out March 2) begins. Coodie is still showing up with his camera when and where he can, but he notes that “I guess things change when you get famous, ‘cause Kanye said he wasn’t ready for the world to see the real him. He told me he was acting now, playing a role.” And then in November of 2007, tragedy strikes when Donda West dies suddenly of complications following cosmetic surgery. Her son continues working, now at a more feverish pace than ever, but is clearly rattled, and in an early 2008 studio session, he signals to Coodie to stop filming—"and then,” says the director, “for the next six years, that’s exactly what I did.”

That era saw West achieve some of his greatest work (808s & Heartbreak, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy) and some of his most notorious and provocative moments (bum-rushing Taylor Swift at the MTV Awards, marrying Kim Kardashian). Coodie is clearly confused about everything that’s happening with his friend, and after 2014, when he starts occasionally turning up again with his camera, he is baffled by the rapper’s onstage rants and meltdowns. “I just thought it was part of the show,” he says. “I had no idea he was struggling with his mental health.”

The filming falls into a pattern: West has some incident, Coodie and crew fly out to make sure he’s OK, and for the moment, he largely keeps it together—but less and less as time goes on. The third episode is far more dependent on the filmmaker’s narration, filling in these gaps over the last fifteen years. Montages cover West’s embrace of Donald Trump and the tabloids’ obsession with his wife and kids, which is mostly presented without comment. When the documentary team is invited to West’s studio in Cody, Wyoming in 2019, the rapper is focused on delivering born-again sermons.

In 2020, after the pandemic shuts down the world, Coodie and Chike decide it’s time to finally complete the documentary, only to find out that West has announced his preposterous candidacy for President. They join him in the Dominican Republic, and attempt to film a meeting with some real estate developers, but West is so unhinged that they turn off the camera. Even this late, we still get to witness some truly intimate moments, like the rapper on the phone with his father, but while the viewer sympathizes with his (clearly very real) struggles, it becomes painful to watch.

There’s no real ending to jeen-yuhs, because how could there be? Just this week, we’ve seen Kanye West attacking Billie Eilish and Pete Davidson on Twitter, breaking up with new girlfriend Julia Fox, and booed at the Super Bowl. There’s supposed to be a new album out next week, but who the hell knows? The film inevitably comes up short at explaining what has really happened to this extraordinary artist; obviously he has never been the same since his mother passed, but the blend of ego and loss and desire and mental issues which has gotten him to his current state is unknowable even to those closest to him.

If you’re sick of Kanye West, I can’t blame you. If you don’t want to deal with him for four-plus hours, it’s tough to argue—but you’ll be losing out on an intimate and insightful portrait of the artist as a young man. Maybe it was West’s Muhammad Ali-style arrogance that allowed these cameras so much access for so long (though that would hardly be unique: the childhood scraps displayed in the David Bowie Is museum exhibit also revealed someone who knew he was destined for some kind of greatness from an early age). Regardless, we should be glad that he did. And whatever nonsense Kanye is up to today, what matters is what Coodie observes at one point on this very long, very strange trip. “He always seemed to be in his best spirits when he was creating.”

You Might Also Like