Inside the Unsolved Murder of JFK's Mistress Mary Pinchot Meyer

On a brisk autumn day in October 1964, Washington D.C. socialite and painter Mary Pinchot Meyer was out for an afternoon stroll on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal towpath in Georgetown, a route she often took, when she was shot and killed in broad daylight. A 25-year-old African American man named Ray Crump was arrested, having been found near the crime scene. The lack of evidence, though, eventually lead to his acquittal.

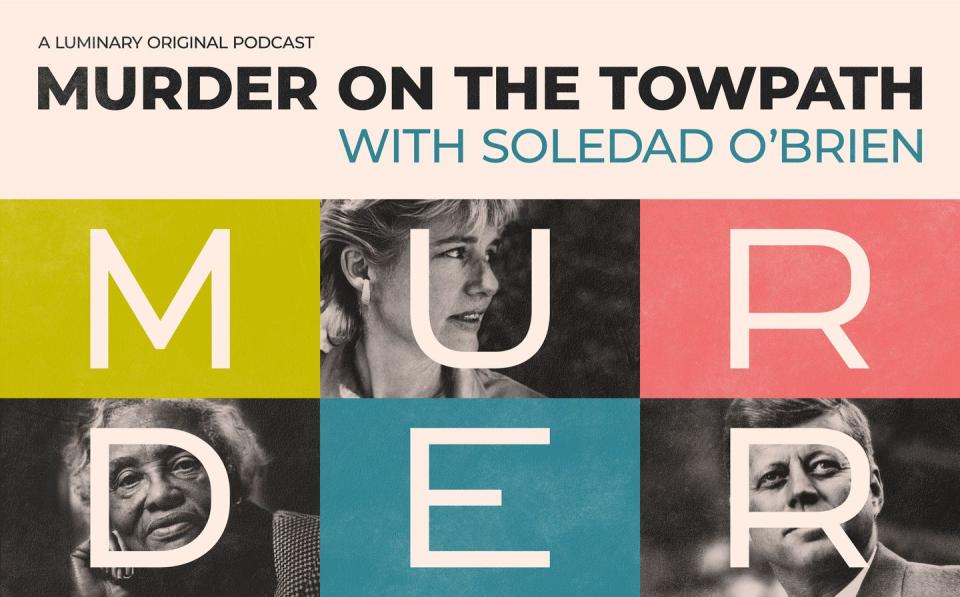

To this day, the murder remains unsolved, but the case is still the subject of fascination to many, inspiring memoirs, novels, a TV series, and now, a new podcast, "Murder on the Towpath," by Emmy-winning veteran journalist Soledad O'Brien that premieres today on Luminary, the subscription podcast network.

Who Was Mary Pinchot Meyer?

Why the endless fascination? For one, Meyer was a very well-connected socialite with a social pedigree. Her father was a wealthy lawyer, her mother a journalist, and an uncle had served as a two-time governor of Pennsylvania. She was educated at Manhattan's prestigious Brearley School, and then went on to Vassar, and had married a high-ranking CIA official named Cord Meyer, whom she divorced in 1958.

She counted Jackie Kennedy as a friend; the Kennedys had moved in next door to the Meyers in 1954 and the two women took walks together, often on the same path where Meyer was later murdered. Ben Bradlee, who would go on to lead the The Washington Post and become a folk hero after Watergate, was her brother-in-law (he was married to her sister Antoinette).

She was also John F. Kennedy's mistress. The two had known each other since high school, when they met at a school dance at Choate, and struck up a secret romantic relationship after her divorce. She would visit JFK at the White House when Jackie went out of town. In October 1963, a month before he was assassinated, the president wrote a letter to Meyer imploring her to visit him in Boston or on the Cape. "Why don't you just say yes," it read. The letter, which was never sent and remained with JFK's personal secretary Evelyn Lincoln, went up for auction in 2016 and sold for nearly $89,000.

What Happened to Her?

Meyer lived in Georgetown with her two sons, where she had moved after her divorce and became an artist; she spent most of her time painting in her studio. On October 12, 1964, at around noon, she left for her daily walk on the towpath along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. There she was shot twice.

In just 45 minutes, the police apprehended a suspect, Crump, who was found nearby, his clothes soaked. He said he had been fishing, dropped his pole, and fell into the canal while trying to retrieve it. Legendary civil rights attorney Dovey Johnson Roundtree became Crump's defense lawyer and he was acquitted of all charges in July 1965. The murder was never solved.

Meyer's Relationships with JFK and the CIA Has Fueled Several Conspiracy Theories

Meyer's illustrious social connections—plus the shock that something like this had happened in tony Georgetown—made this crime particularly salacious. And her affair with Kennedy and her connections to the CIA, an organization she openly criticized, inevitably fed the conspiracy-theory machine. Was the CIA behind both Meyer's and JFK's deaths, with their alleged killers the scapegoats? Did the CIA order the hit because she knew too much?

Several things fueled the speculation: The execution-style manner of her killing, a close-range shot to the head and one to the chest. Then, the fact that her death occurred a few weeks after the release of the Warren Commission (which concluded that JFK's assassination was the work of a lone gunman) further fanned the flames, since she allegedly challenged its conclusions.

Finally, there was the fact that the CIA was wiretapping her phone and its counterintelligence chief was found trying to break into her studio to find her diary after the murder, likely to prevent details of her affair with JFK from becoming public,

But Meyer Isn't the Only Fascinating Woman at the Center of This Story

In "Murder on the Towpath," O'Brien delves deeper into the unsolved mystery of Meyer's death by shifting focus away from all the conspiracy theories and to the women at the heart of this story. Meyer is one, of course, and the other is Dovey Johnson Roundtree, the trailblazing civil rights attorney who successfully defended Meyer's accused killer and got him acquitted.

"It's very easy to go to conspiracy theories. Sometimes they're wacky, sometimes they're interesting," says O'Brien, who spent nine months investigating the case, interviewing friends, relatives, historians, and biographers, and consulting memoirs, especially Ben Bradlee's, for the eight-episode series.

"But what was really compelling was this idea of these two women who were both trying to figure out how to live their lives in 1964. I thought the 1960s was an interesting era to think about for women and how they were often thwarted, whether they were rich and white or poor and black."

Roundtree, who died in 2018 at the age of 104, grew up in the Jim Crow South and worked her way up to become a civil rights champion who broke several racial and gender barriers throughout her life. She was one of the first women to be commissioned an Army officer, she secured the ban on racial segregation on interstate buses, and, in 1964, she took on Crump's defense for just $1—and secured his acquittal.

That Roundtree, an African American woman, was able to get a poor, black man acquitted of murdering a very rich, white woman was a historic achievement, especially in 1960s America, a period of immense civil unrest.

It's how the trajectories of Meyer's and Roundtree's lives aligned, even though the two women never met, that interested O'Brien. She wanted to make these women—not the men around them—the focus, something that hasn't been done for the past 50 years. "Technically they're at the center of the story: one is murdered and the other is a person who argues a case she's expected to lose. Yet historically they've been moved off the center," she says. "It's a metaphor for how women were treated in the 1960s."

There's a telling moment that O'Brien recounts in the first episode: a police officer examining Meyer's dead body at the crime scene proceeds to make a comment about how pretty she is. "It felt like an important element because it speaks to the people of this story constantly being rendered powerless," she notes.

As for those conspiracy theories, O'Brien does address them. "For me as a reporter the key is to have transparency," she says. "You can't ignore them because they exist."

But "Murder on the Towpath" goes far deeper into the layers. It's a true crime story about two compelling, strong, and independent women, plus history, mystery, and a lot of twists and turns. Says O'Brien: "There's so much more to this case than just conspiracy theories and a love affair with JFK."

You Might Also Like