Inside the ‘Green Science’ of Beauty

It may have less fanfare than the “clean beauty” movement, but “green science” is about to be the beauty industry’s next big thing.

The concept is an offshoot of green chemistry, which is a formalized and defined scientific approach meant to reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances, including pollution.

More from WWD

Like “clean beauty,” “green science” has no official definition, but experts in the industry contend that it relates to product ethics, sustainability and sourcing, and that it’s been driven by increasing consumer demand for transparency. Plus, for an industry that is primarily marketing driven, “green science” also unlocks the potential for fresh innovation, experts say.

According to Jasmina Aganovic, entrepreneur in residence at Ginkgo Bioworks, beauty innovation has been driven by branding and marketing lately. And as consumer education around beauty and ingredient sourcing has increased, shoppers have started to look into individual ingredients to try to determine the differences between their myriad brand options.

“Green science” has the potential to provide more avenues for innovation.

“If you think about clean beauty, it was innovation by absence. So what can additive innovation do? Innovation that is aligned with modern consumer values, what does that look like? There’s a space for that,” Aganovic said.

As it relates to the beauty sphere, “green science” includes biotechnology, where different companies are brewing up ingredients instead of extracting materials from nature. It also includes manufacturers mixing up their own replacement ingredients for certain silicones, as well as microplastics and talc. It will also likely have meaningful applications in packaging as single-use plastics fall out of style, and corporations look for refillable, biodegradable and recyclable options.

Prudvi Kaka, Deciem’s chief scientific officer, said he is also watching plant cell culture-derived technologies, plant-based transient expression systems and living-root exudation, which he finds promising.

L’Oréal, the world’s biggest beauty company, has made major commitments to “green science.” By 2030, 95 percent of the ingredients L’Oréal uses in products are to come from renewable plant sources, minerals or circular processes, and will be conceived to respect aquatic environments. Today, that level is 59 percent, and by 2025, L’Oréal expects to reach 80 percent. Chief executive officer Nicolas Hieronimus has said he considers that with “green science,” the company is starting a new chapter in its research and innovation.

Courtesy of Biossance

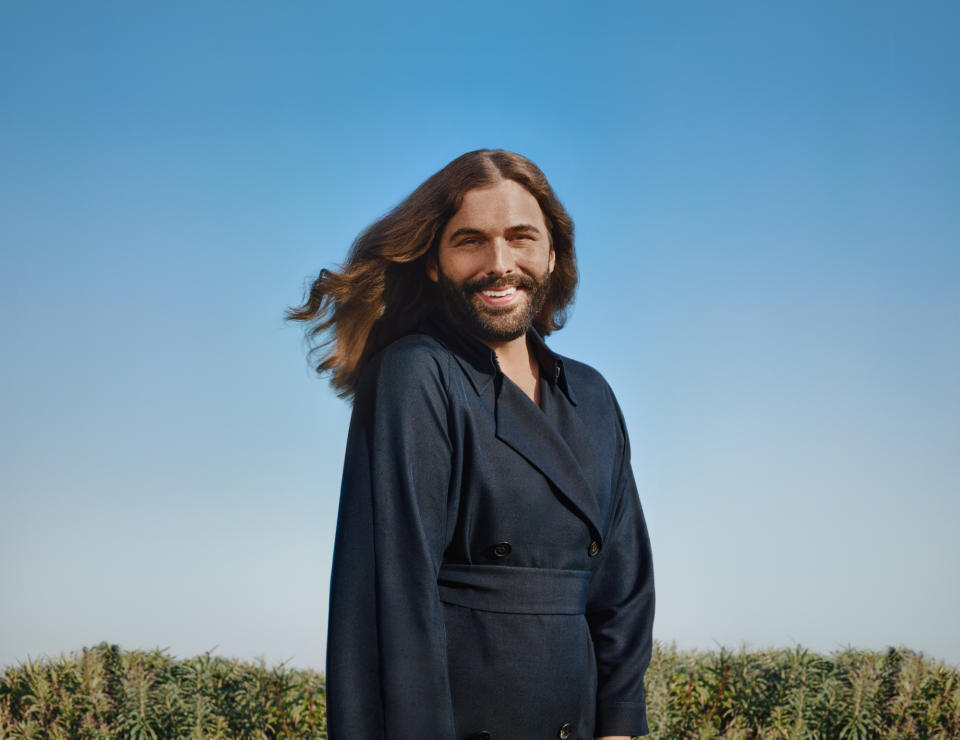

“We’re seeing a lot of demand,” said Annie Tsong, chief strategy and product officer at Amyris, a biotechnology company that develops ingredients and owns several brands, including Biossance and Jonathan Van Ness’ JVN. “It comes from the end consumer and a really evolving view of what a product needs to be for them. They want sustainability, they want transparency in how the ingredients are sourced and they want that combined with efficacy.”

Tsong said there’s also “tremendous pressure” on big beauty companies “to really ramp up the environmental friendliness of their products. A lot of companies are trying to figure out how they can get bio-based ingredients, things that are from renewable carbon, rather than petroleum — that’s a major priority.”

At L’Oréal, research will center around natural sciences, agronomy, biotechnology, eco-extraction, green chemistry and physical chemistry, said Barbara Lavernos, the group’s deputy CEO in charge of research, innovation and technology, at the time of L’Oréal’s major “green science” announcement in March.

“This is how we will revisit our portfolio of raw materials and formulation, and integrating the principle of circularity will enable us to penetrate new areas of innovation,” she said.

The group is to use green sciences for the sustainable cultivation of its product ingredients and the latest technology to extract the natural raw materials. Then, most of the basic ingredients will need to be transformed through eco-extractions, bio-fermentation or green chemistry, to be more performant with the least negative impact on the environment.

The Green Sciences program also allows L’Oréal to identify possible gaps in its processes, and home in on some technologies that it does not yet have but should be put in place to meet the goals.

“It allows us to lead not only our internal organization, but also our consumers toward using the most sustainable products and even routines that are more sustainable,” explained Delphine Bouvier, L’Oréal research and innovation international director, Green Sciences Transition program.

Today, about 30 percent of L’Oréal’s active ingredients for formulas stem from green chemistry. One example is Pro-Xylane, a sugar-molecule used in anti-aging products.

L’Oréal also has a biotechnology plant in Tours, France, where specific rose cells are being cultivated in vitro for the Lancôme brand, making it possible to reproduce those cells exponentially without negatively impacting nature. Hyaluronic acid is also being made that way.

L’Oréal also takes a “hybrid” approach, whereby some products are being formulated or reformulated with a mix of green and traditional ingredients.

Hair color is an example. Historically, it’s a product that’s highly synthetic, made from petrochemicals.

“Here, too, we are entering a system of green formulation and hybrid products, where little by little we are able to introduce natural dyes, which are, for example, from henna, indigo,” she said.

However, such dyes don’t yet allow for the whole color palette consumers expect today.

L’Oréal’s scientific advances will also come with assistance from external partners, including a small start-up.

Global Bioenergies, which developed a process to convert plant-derived resources into important ingredients used in the cosmetics industry. L’Oréal is an investor in that business.

<img class="size-medium wp-image-1234951469" src="https://wwd.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Unknown.jpeg?w=300" alt="L’Oréal has a biotechnology plant in Tours, France, where it works on “green science” projects. - Credit: courtesy of L'Oréal" width="300" height="132" srcset="https://wwd.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Unknown.jpeg 775w, https://wwd.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Unknown.jpeg?resize=150,66 150w, https://wwd.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Unknown.jpeg?resize=300,132 300w" sizes="(min-width: 87.5rem) 1000px, (min-width: 78.75rem) 681px, (min-width: 48rem) 450px, (max-width: 48rem) 250px" />courtesy of L'Oréal

“We actually need external ecosystems to increase capacity, bring it to maturity so that tomorrow’s costs will be more affordable for the world of cosmetics,” said Bouvier.

The possibilities for sustainable and natural beauty product manufacturing have evolved dramatically from when the concepts started circulating roughly 25 years ago, according to Arabella Ferrari, senior vice president of makeup at beauty manufacturing business Intercos.

Back then, using natural ingredients resulted in products with performance that wasn’t up to par, she said.

“The real difference is today we can get performance,” Ferrari said.

It has taken years of development, but Intercos scientists have been able to craft a combination of raw materials that mimic the sensory performance of microplastics, Ferrari said. “We had to challenge our raw material lab,” she said. “We create blends or compositions which then act in formulations and give you the performance of microplastics … they have to give me in the formula what they’re supposed to give me, which is sensoriality, softness, skin-like adhesion, wear, the whole cosmetic performance.”

Intercos has also been able to mix up a replacement product for D5, a silicone that is now banned in Europe, Ferrari said.

“There’s a lot of different silicones. There’s good silicones and bad silicones. There’s a few which are bad, such as D5 and replacing that is one of the toughest objectives we’ve had,” Ferrari said.

Those replacement ingredients are what allow today’s “clean beauty” products to have better performance than “natural beauty” historically have had.

Intercos has also created a talc replacement, and internally, has set up tiers that clarify how “clean” its different formulations are, Ferrari said. Clean Magnifique is the top tier, and eschews nanoparticles, as well as fragrance allergens, chemical UV filters and some mineral oils. Below that, there’s Pure Clean, which is Intercos’ take on clean, and must be good for people and communities, as well as the environment. Then, there’s Sephora Clean, which meets the standards for Clean at Sephora, and then there’s Clean Tech, which uses some green chemistry.

The business is constantly working to develop new ingredients, Ferrari said, and now considers itself ahead of the curve. “Makeup moves very fast, ingredient stories move very fast. We always have to work on pigments. There’s a whole lot of treatments and coatings we do to pigments that have to continue in the natural and sustainable way, and that will be an evolution forever.”

Intercos also continues to work on long-wear makeup products, which have not yet been perfected for the “clean beauty” segment — “We haven’t gotten to a level which is acceptable yet on a lot of semi-permanent or non-transfer products,” Ferrari said.

Like Intercos, Amyris has its own standards when it comes to “green science.”

The company checks that ingredients are sustainably and ethically made, as well as safe for the consumer and the earth, said Tsong. But, “that’s not necessarily the definition that everybody has right now,” she added.

“Green science,” Tsong said, “is a very big mishmash of concepts right now. Clean and green is just not something the industry has agreed on right now as to what it means, and that actually puts a lot of noise into the system and can make it very confusing for customers.”

Photo courtesy of JVN

Amyris uses biotechnology in order to develop ingredients that it either sells exclusively to customers, or broadly to the larger beauty community. The company is best known in beauty for its squalane, used as a replacement in products for squalene, which had historically been derived from shark liver.

Amyris develops ingredients by using yeast to covert sugar into specific end ingredients. Amyris uses non-GMO sugarcane, which grows quickly, for the process.

The company has also developed a molecule called hemisqualane that Tsong said can be used as a replacement for silicones, including D4s and D5. “The product it’s sort of a doppelgänger for these cyclopentasiloxanes,” she said. “They’ve been banned in Europe because there is some evidence out there that they actually persist in the environment and actually may bioaccumulate in some aquatic life forms.”

Right now, Amyris has commercialized 13 different molecules using biotechnology, including some that are licensed exclusively to fragrance partners, Tsong said, as well as some that are used medically, like malaria medication Artemisinin. Amyris has also created CBG, cannabigerol, and is working on “bio silica” from its sugarcane waste stream, she added.

“We are really leaning into the circular economy and adhering to the principal of using every part of the plant that we can to develop products for the industry,” Tsong said.

Amyris is also using the sugarcane waste stream to develop secondary packaging for Biossance, and Tsong said she sees the need for “green science” to apply to packaging, too.

“We know that a huge proportion of ocean plastic is from beauty care and personal care products. It’s a really urgent area to be addressing and there’s so many different ways that you can go about it.”

“It’s not super well known, but Amyris has actually had a lot of activity in the past in materials so we’ve worked with some big companies on things like rubbers and elastomers, adhesives and so on, all from sugarcane,” Tsong said. “That’s taken a while for that portfolio to take off because there’s such a long testing cycle for those types of materials, but it’s starting to gain a lot of momentum and we’re starting to look for those synergies between those materials we developed five, 10 years ago, and our needs now as an emerging beauty care and CPG company.”

Intercos is also working with sustainable packaging offerings, including biodegradable materials like polylactic acid (sugarcane) packaging. Ferrari said she sees demand for more sustainable packaging, especially in using fewer virgin materials. “Refillable is the biggest trend right now in terms of what customers are looking for, and then being able to recycle the product,” she said.

Beyond developing sugarcane packaging, Amyris has more than 20 molecules in development right now.

To pick which molecules it develops, the company looks at consumer trends, and evaluates sourcing and pricing pain points with the goal to “de-bottleneck” beauty’s supply chain, Tsong said.

“We’re finding things that are really rare and really expensive in the industry right now, where we’re in the position to de-bottleneck the supply and provide it in our products to the market at a much lower price point and in much larger volumes than that are currently physically possible with the technology,” Tsong said.

Aganovic, with Ginkgo, gave sandalwood as an example: To harvest sandalwood, the tree needs the care and resources to grow for 10 years, and environmental factors would be out of the grower’s control, Aganovic said.

“That is resource-intensive, that is land-intensive,” she said. “With biotech, you can grow that same amount that was taking 10 years to grow in 10 days,” with a purity that can’t be replicated in nature.

“The entire industry is predicated on extracting materials from our environment, whether it’s petrochemicals, plants, animals. The basis for the ingredients for which we construct our formulas necessitates some sort of extractive relationship with the environment. What I’m so excited about biotech for is that you can cut that cord. You can now start to grow ingredients in a way that is much more traceable and sustainable,” Aganovic said.

For more from WWD.com, see:

What Lab-Engineered ‘Naturals’ Mean for the Beauty Industry

L’Oréal Adopts a ‘Green Sciences’ Approach

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.