Inside Country Music's Most Ambitious, Oddball Album of the Year

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

No one actually knows where the cabin is.

Singer-songwriter Ashley McBryde, feeling the buzz of inspiration, decided that she wanted to convene some of her favorite collaborators for a writing retreat. Her friend Nicolette Hayford, who performs as Pillbox Patti, was tasked with finding a location—but two years later, the best she can offer up is that it was somewhere on Kentucky Lake, about two hours outside of Nashville. McBryde just claims to have no idea.

“It’s like we fell into a vortex,” says Hayford. “I've looked for it again, and I can't find it.”

Of course, it’s only fitting that the house is shrouded in such mystery, since the point of the whole project was to conjure up, as McBryde puts it, “a town that doesn't exist, except that it's every small town you've ever been to.” The result is Ashley McBryde Presents: Lindeville, country music’s most ambitious and oddball album in recent memory.

OK, maybe we need to back up. McBryde, 39, is one of the most acclaimed country artists to emerge in the last few years. Her first two major label records were both nominated for Best Country Album Grammys. In 2019, she won trophies as ACM New Female Artist, CMT Breakout Artist of the Year, and CMA New Artist of the Year. She’s up for five CMA awards in November, including her third consecutive nod for Female Vocalist of the Year, and she recently had a Number One single with “Never Wanted to Be That Girl,” a duet with Carly Pearce.

McBryde came up playing in biker bars in her native Arkansas, and she’s made her mark with closely observed lyrics about the world she knew, full of complicated and troubled American lives. Working on a new song one day, she noticed a pattern in the work that she and her friends were doing. “I was writing with Nicolette and Aaron Raitiere,” she says, calling from a parking lot in Omaha (which almost sounds like one of her song titles). “I was hung over and had really bad hangxiety—if there was a US Olympic team for hangxiety, I’d win the gold. So, we wrote this song called ‘Blackout Betty,’ which is my nickname when I party too hard. It was around the time Pillbox Patti was born, which is Nicolette’s nickname when she parties too hard.

“I was like, hang on, we've got Blackout Betty and Pillbox Patti, and Aaron had this song called ‘Jesus Jenny.’ And [on previous albums] I had ‘Shut Up Sheila’ and ‘Livin’ Next to Leroy,’ and I was like, we managed to accidentally collect all these really strange characters. They’re either people that we've been at different times in our lives, or people that we know, or people that we ran into. So I thought what we should do is give them neighbors and a place to live.”

It was late September of 2020 (McBryde can only confirm the date by checking the photos on her phone, otherwise she says it would be lost in the blur of “the Great Separation—which is a lovely, romantic thing to call COVID”). Hayford found the clandestine cabin (“this quirky house that felt like a house that was maybe in the town we were going to create,” she says) and they sent up a flare, seeking some of the finest songwriters in country music to lock themselves in for a week and help chase down their vision. In addition to Hayford and Raitiere, they were joined by Brandy Clark, Connie Harrington, and Benjy Davis—an all-star team loaded with Grammy nods and credits on Number One hits, but with skewed sensibilities far from the limitations and overly sentimental formulas of Nashville.

The objective was clear—if, that is, it turned into anything at all: to capture a complete and honest representation of an American small town, warts and all (and maybe mostly warts). That setting, of course, is a staple of country music, a wholesome image of unspoiled values right up there with fishing and trucks and beer in a cooler.

“Country music is known for that superficial side of a small town that we all have in common,” says John Osborne of the Grammy-winning duo Brothers Osborne, who produced the Lindeville album. “But every small town is unique. And what makes it unique are the characters that make that town run. Within those characters, you're going to have some serious drama and serious stories. Once you start digging deep, you realize that we all have our own set of problems and worries and fights and feuds and it's what makes your town special.

“I couldn't help but think about my own hometown, which is Deale, Maryland,” he continues. “And there's not one character—there are hundreds of them, and they're all crazy and beautiful in their own way. They all have a story to tell, and they're all individuals, but they're all connected.”

There was also another inspiration for this uncertain undertaking. Dennis Linde was a legendary Nashville songwriter, who created such classics as “Burning Love,” Elvis Presley’s last major hit, and “Goodbye Earl,” the Chicks’ riotous revenge fantasy. He was an eccentric, reclusive figure, a guy who gave himself the assignment of writing songs starting with every letter of the alphabet. Famously, Linde had a map on his wall of a town where all the characters in his songs lived, and he would plot out their movements and interactions. Just look at those song titles—“Bubba Shot the Jukebox,” “Queen of My Double-Wide Trailer,” “Janie Baker’s Love Slave.”

“He did it kind of the opposite of the way we did it,” says McBryde. “He created a fictional town, and he would look at that town and develop characters and then write songs about them. And here we were, with characters that we already had, and we're developing a town about them. I don't know what we would have called this damn town or this damn record but Lindeville—it’s a tip of the hat to say, we love this idea, but we didn't get there first.”

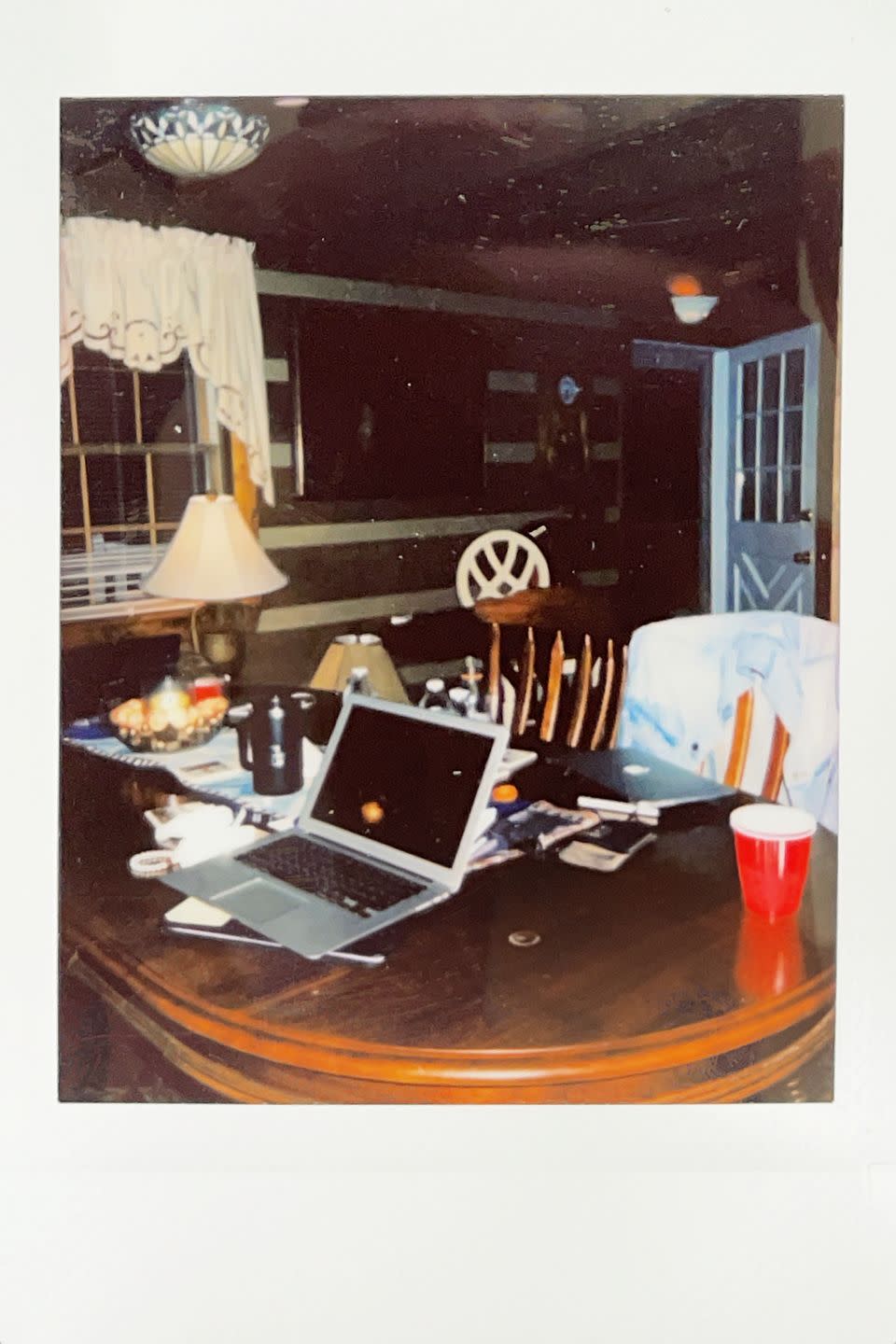

The scene at the writing cabin? Well, it was about like you’d expect. “It felt like we were a family on vacation at this weird-ass Airbnb,” says McBryde, “and we were putting a puzzle together at the kitchen table and nobody wanted to get up.”

That kitchen table was ground zero, littered with laptops, notebooks, sketch pads, and “various substances to alter your state, if you chose to—there's tequila, Jack Daniels, there's all kinds of shit.”

“Five cars in the driveway, instruments everywhere, there's a full ashtray overflowing on the porch,” adds Hayford, who was named Music Row magazine’s 2021 Breakthrough Songwriter of the Year. “Some of us sitting at the table, some of us yelling lines from the kitchen as we're cooking, somebody's yelling lines from the porch while they're smoking. It's chaotic, but very focused.”

Lindeville tosses you straight into the action. The opening track, “Brenda Put Your Bra On,” depicts some mayhem popping off at the trailer park: “Grab a pack of cigarettes and meet me on the porch/Marvin’s baby mama ‘bout to catch him with a whore,” a chorus of female voices sings over a jaunty, rocking track.

“I lived in a small town,” says Hayford, “and when something crazy was going on with the neighbors, somebody's fighting, it would be this chaotic moment and ‘Get outside and see what's going on!’ So right from the jump, I was in it in kind of a personal way.”

Local married folk try to hook up discreetly through “The Missed Connection Section of the Lindeville Gazette,” while the town’s real secrets are tracked with the eyes, ears, and snouts of the local hounds on “If These Dogs Could Talk”—“They could sniff out the cheaters and point out the liars/Shit on their lawns and piss on their tires.”

“Coming at a small town from the point of view of an animal was fun,” says McBryde. “We wrote that over sandwiches when I was having lunch, just cracking ourselves up.”

Not all of Lindeville is about exposing dirty laundry. “Bonfire at Tina’s” describes a group of women meeting up to pass around a joint, unified by the hurt they’re going through (“When Monday comes around yeah, we’ll be back to talkin’ shit/But tonight we’re all just bitches that are sick of takin’ it”).

Most sentimental is “Play Ball,” a description of Pete, a wise and kindly widower who “chalks the ballfields down at Dennis Linde Park.” For this one, they brought in TJ Osborne (the other half of the Brothers Osborne) to deliver the song in his classic, sonorous voice.

“I love that song, it's a special song,” says McBryde. “And when you put TJ’s voice on it, I don't care who you are, or what your relationship is with your family, when you hear him sing ‘Go to church, love your mama, and play ball,’ it makes you want to call home.”

Some of the Lindeville material came from real life (Hayford notes that “Play Ball” co-writer Benjy Davis “kind of had a Pete in his life”), but others came from jokes, images, emotions—it was all fair game. “We really just sat down to write whatever song was fixing to come out,” says McBryde. “We wanted to make more characters, but we didn't really have a plan. I literally dreamed the song ‘Gospel Night at the Strip Club.’ I called Brandy Clark, and said, ‘Oh, my God, I had this dream where you and I walked into my house with this big wad of cash. And the people at my house were like, ‘What are you girls doing?’ And we said, ‘It's gospel night at the strip club!’”

Once there was a set of songs that had been recorded and tentatively sequenced—complete with interstitial commercials for the “Forkem Family Funeral Home,” the “Dandelion Diner,” and “Ronnie’s Pawn Shop” (“We don’t ask, we don’t tell/We just buy, we just sell”), all knocked out on the smoking porch—McBryde played them for her manager and for friends like Miranda Lambert. “Their reactions let me know that I actually wanted this to be a record,” she says.

While producing, the biggest challenge for John Osborne was retaining the spirit of the rough work tapes. “You could tell that there was a lot of weed and whiskey involved, and they're goofing off and laughing,” he says. “But then there were a few moments where the singers got in the studio and they were singing quote, unquote, correctly. And I'm like, ‘That's not how you sang it on the work tape, we need to loosen up.’ There were a couple of times where I told them to turn themselves off in their headphones. And as soon as they stopped hearing themselves, they took on a whole new persona.”

“John O killed it,” says Hayford. “He took those work tapes and made them sound exactly how all of us heard it in our head—which is a very rare thing to happen with somebody that wasn't connected to the writing process.”

McBryde has no real idea what’s going to happen with this album. Hell, she never had any intentions for it in the first place. For now, there’s a Lindeville website that’s getting populated with stuff like the front page of the Lindeville Gazette and videos with the “TV versions” of the record’s radio jingles. But she does dream of making the made-up town come alive.

“In a perfect world, it needs to be a live show,” she says. “In my heart, it would be at the Ryman, done in the style of a community theater, kind of Prairie Home Companion it. To deliver those performances in that way I think would be really beautiful and a lot of fun.

“When it comes out,” she continues, “I hope everybody laughs a little bit and I hope everybody says ‘What the fuck?’ a little bit. Sometimes you look and realize, this town is such a mess, everybody here is a disaster. And in the same breath, in that same three minutes, everybody's okay. And I love those times. Sometimes I wish I could make that stand still a little bit longer—we're all a disaster, and it's beautiful. And that's true whether it's a small town or a big city.”

You Might Also Like