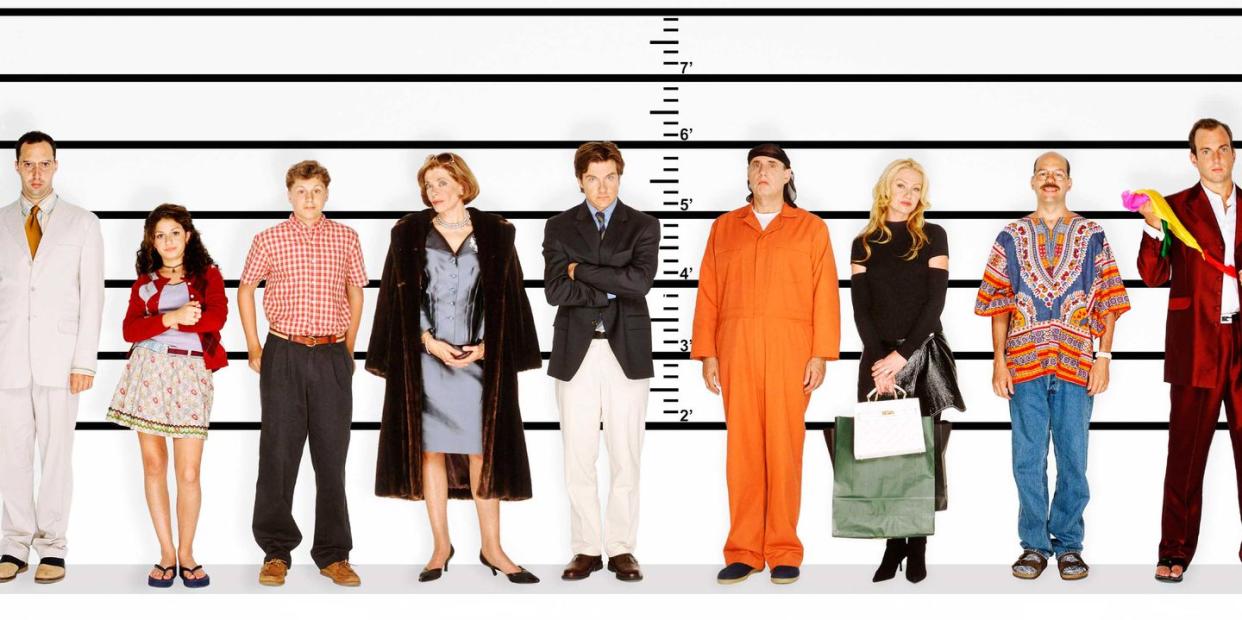

Inside the World of Prison Consultants Who Prepare White Collar Criminals to Do Time

Given the recent reports that Lori Laughlin has hired a prison expert to prepare for possible jail time if she is found guilty in her upcoming trial related to the college admissions scandal, we're resurfacing this story, which appeared in the October 2019 issue of Town & Country.

So you got caught. That porn star wasn’t about to pay herself to stay mum about her night with your boss, so you stepped up and took one for the team. Or perhaps your daughters were better at Instagram than calculus, so you spent half a million bucks pretending they were the best college athletic prospects since O.J. Simpson. Or maybe the SEC decided you were less of a “cryptoguru” and more of a charlatan.

From Felicity Huffman to Michael Cohen, nearly every day brings a notable figure face to face with a possible jail sentence—which, in turn, has given rise to a cottage industry: the prison consultancy. From companies like California’s White Collar Advice, which boasts a team of professionals with penal experience (as convicts or as employees of the Federal Bureau of Prisons) to individual entrepreneurs like Federal Prison Handbook author Christopher Zoukis, they have made it positively de rigueur for those more accustomed to sleeping between Pratesi than polyester to hire an insider who will lay out what to expect when expecting to be incarcerated.

They charge thousands for their advice (and some six figures for help managing your affairs while you are inside), but we rounded up some of the top consultants—as well as some high-profile prisoners—to ask for their most crucial insights. Because, you know, you never know.

Where Exactly Are You Going?

There are essentially two answers to this question: camp and prison. If this was your first bust and your crime wasn’t violent, chances are you won’t be going to prison; you’ll be headed to one of 76 minimum security institutions, six of which are federal prison camps (FPCs), the majority of the rest being minimum security “satellite” camps on the grounds of larger, higher-security prisons.

Because of the on-site amenities and activities, FPCs are considered much more desirable. They include Connecticut’s Danbury and West Virginia’s Alderson, where Martha Stewart went and where Billie Holiday served a year and a day for heroin possession. There’s also New York state’s Otisville, where Michael Cohen is reportedly thriving (alongside Jersey Shore’s Mike “The Situation” Sorrentino).

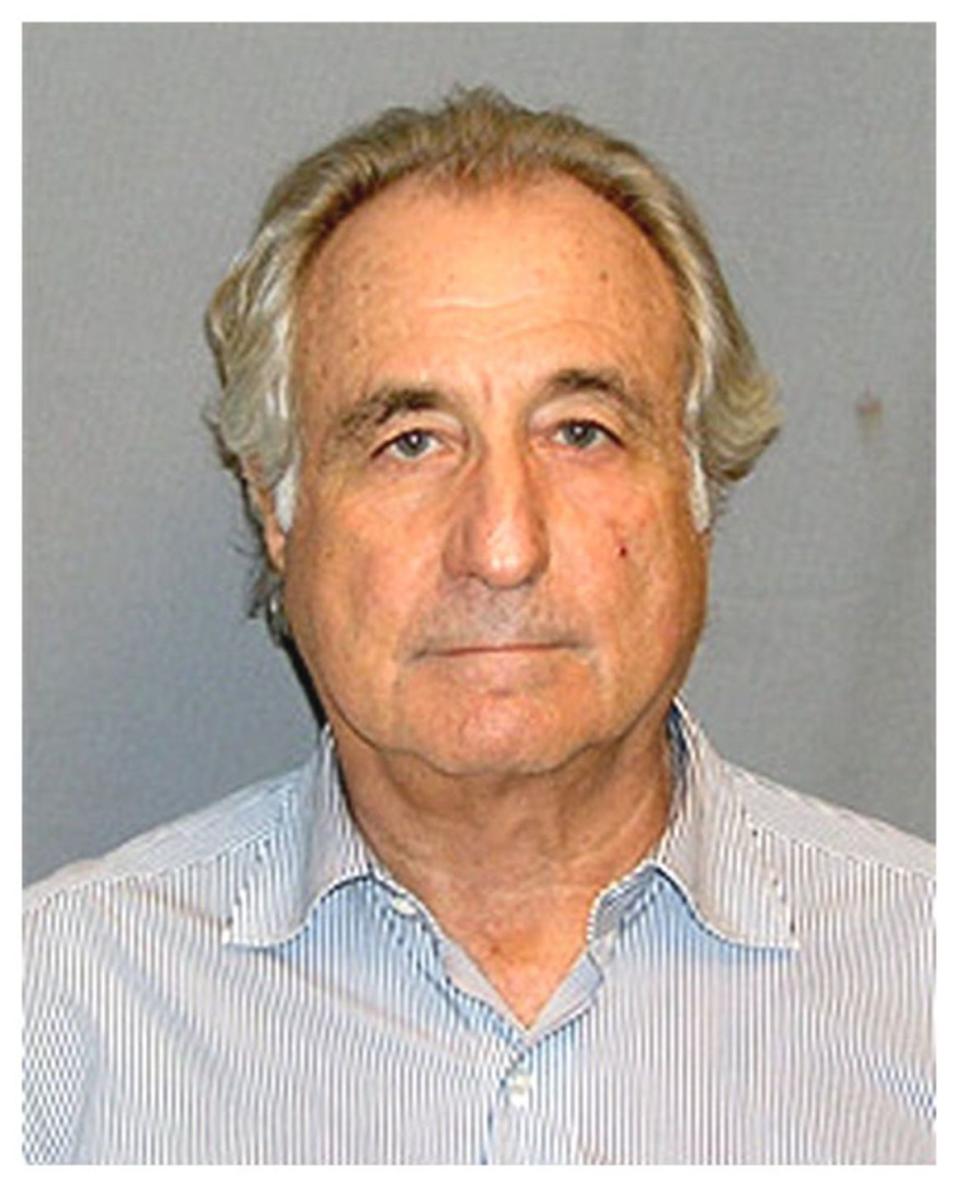

If your crimes were more serious, you’ll head to something stricter than minimum security (i.e., low or high security), where you’ll join the likes of Bernie Madoff, who is serving his 150-year sentence at the Butner medium-security prison in North Carolina. (He’s known to the other inmates as Uncle Bernie, and reportedly he has cornered the market on the commissary’s hot cocoa packets and trades them at a profit.)

There is a vast gulf in quality of life between a camp and any prison. Camps are often called “country club prisons” or Club Fed, a scornful appellation applied to places like Southern California’s Lompoc Federal Prison Camp, where ’80s Wall Street villain Ivan Boesky spent his afternoons playing tennis on lush grounds unencumbered by barbed wire.

In reality, camps are far from luxurious, but you can pretty much go where you want on the grounds when you want, as long as you show up to your work assignment and for “count” twice a day. A real prison has bars on the doors, is surrounded by walls and razor tape, and operates under a system of “controlled movement,” meaning you’re allowed to move between areas of the prison for only 10 minutes out of every hour.

The population will be rougher too. Richard “Dickie” Scruggs, who was once known as the country’s most powerful trial lawyer for having pocketed $1.2 billion in fees after suing big tobacco in the 1990s, served six years for his role in a judicial bribery scandal starting in 2009, one of those years in Ashland, Kentucky’s low-security prison. “It’s a terrible place,” Scruggs says, since, as he reports, it’s “a destination prison, if I can use that term, for pedophiles.”

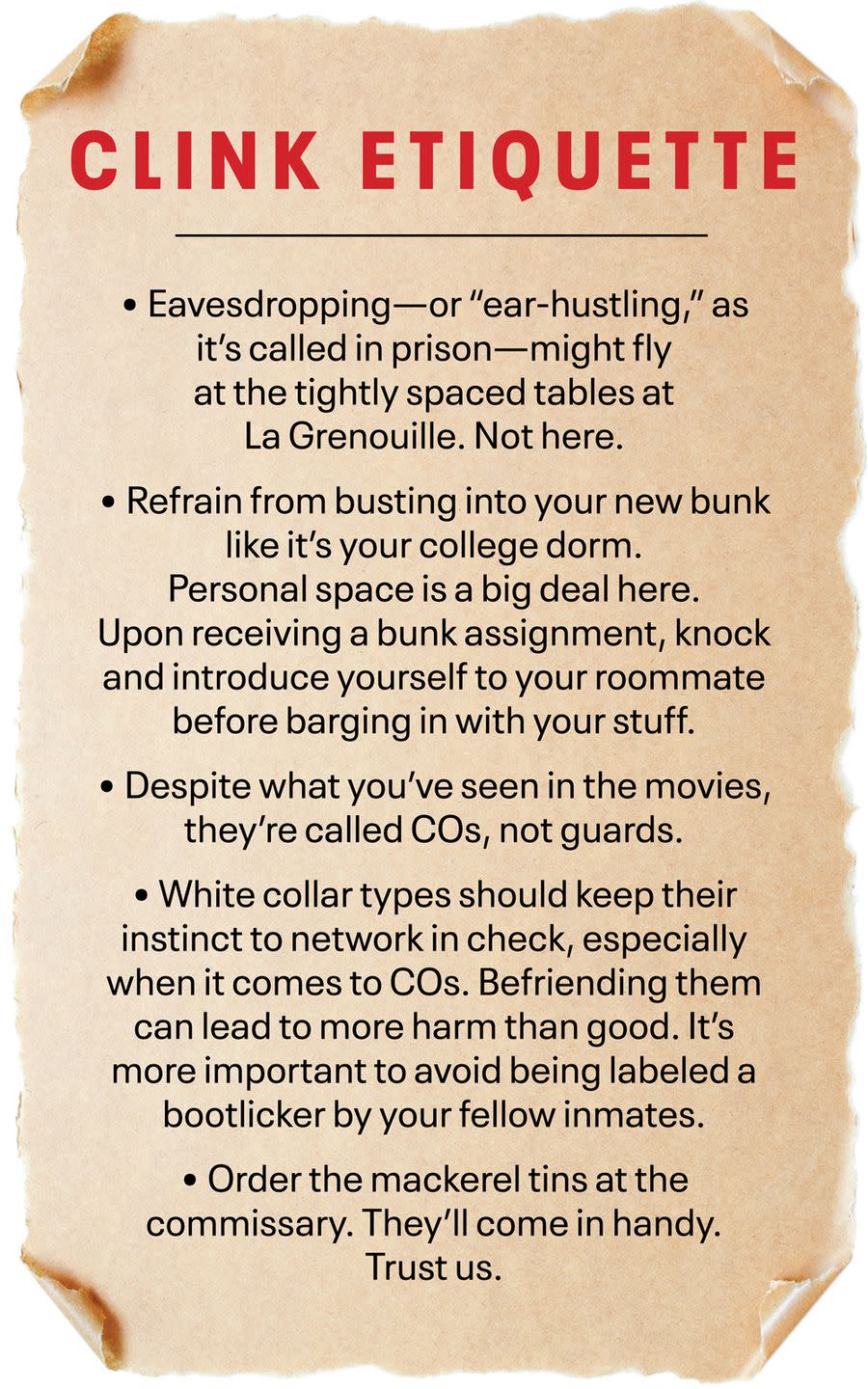

Prison Etiquette Is Serious

Pay close attention to boundaries inside. “Don’t ear-hustle,” says Jennifer Myers, who served her time (for interstate marijuana trafficking) at Alderson and is now a White Collar Advice consultant. “Ear-hustling is listening to other people’s conversations.” Which might fly among the tightly spaced tables at La Grenouille, but not here.

Zoukis, who was a resident of various federal penal facilities for 12 years, advises clients to be very aware of other people’s space; even after you’ve been assigned a bunk, never, ever start moving your things in without an introduction. “Even though you’ve been assigned to that cell, you’re still invading someone’s living space,” he says. “Instead, walk up to the door, leave your stuff outside, knock, and say, ‘Hi, I’m your new cellmate.’”

Zoukis advises clients that they should be much more concerned with their rep among their fellow inmates than among corrections officers, or COs (don’t call them guards—it’s considered disrespectful). “Be polite to the staff, but not friendly,” he says. “Inmates particularly dislike other inmates who suck up to the staff.”

If you’re perceived that way you’ll be shunned, labeled a bootlicker, and even suspected of being a prison snitch, a particularly despised type.

Bone Up On Your Prison Cooking Skills

Make sure to hit all your favorite restaurants, Michael Cohen–style, before heading to prison (Trump’s lawyer rotated among the Polo Bar, Fred’s, L’Avenue, and the Regency before checking in), because camps are not renowned for gourmet fare or paleo-friendly options. “It’s, I guess, akin to an Applebee’s but maybe not as nice,” says Ingrid Okun, who was once a top executive at Tiffany & Co. but pleaded guilty in 2013 to stealing and fencing $2.1 million in jewels while working there. She too works at White Collar Advice now. “But I don’t know,” she adds, “because I haven’t ever been into an Applebee’s.”

Forget about Gotham salads, dressing on the side. Most camps don’t have a salad bar (though Alderson does). Instead you will encounter questionably fresh meat and cheap, carb-rich meals that will undo every Barry’s Bootcamp class you ever took. “One lunch was potato soup, two grilled cheese sandwiches, potato chips, and a donut,” Myers recalls.

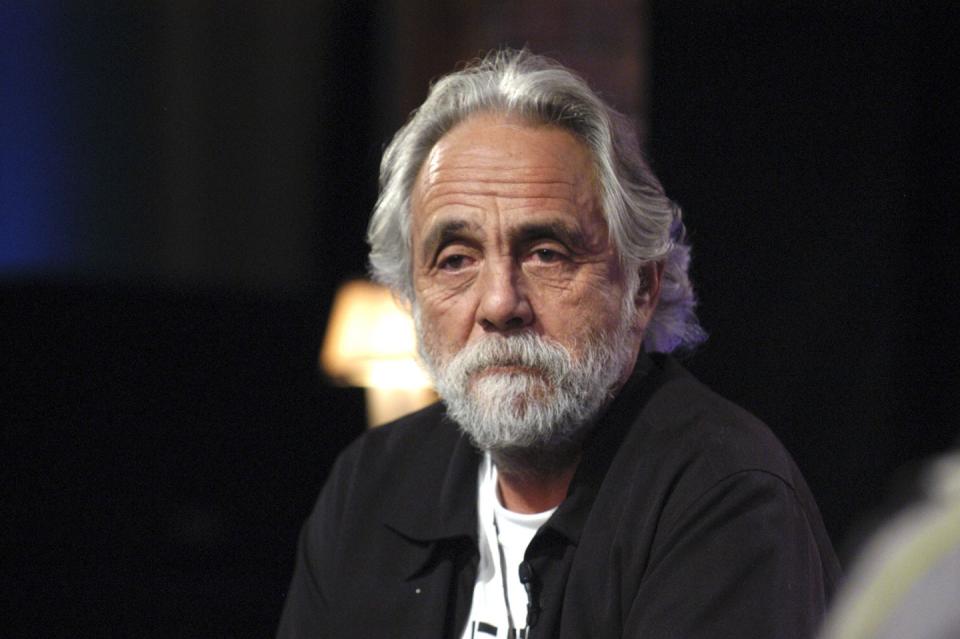

“I think I ate in the dining room maybe twice,” says the comedian Tommy Chong, who was incarcerated in Central California’s Taft Correctional Institute for trafficking in marijuana paraphernalia. His social group (known inside as a “car”) included PGA caddie Eric Larson and “Wolf of Wall Street” Jordan Belfort. “We had our own private Goodfellas kitchen going—we used vegetables from the garden and would buy chicken off other guys, and Eric would make these incredible burritos using chili peppers he grew.”

Prepare to Work the Commissary

You will be allowed to bring virtually nothing into camp save a softcover Bible and eyeglasses. (Fake socialite and high-end grifter Anna Delvey was allowed to keep her signature Celine frames at New York’s infamous Rikers Island.) Visitors can’t bring gifts, care packages are forbidden, and the only jewelry permitted is a simple wedding band or a necklace with a small religious symbol. Paul Manafort had to leave his exotic House of Bijan jackets at home when he checked into Loretto federal prison (which, to be clear, is not a camp) in Pennsylvania.

But every Bureau of Prisons facility has a commissary that offers a variety of packaged food, underwear, socks, and workout gear (including sneakers you’ll want to purchase immediately to replace the uncomfortable steel-toe boots issued to all federal prisoners). Commissaries carry no items that cost more than $100; inmates visit once a week and can spend up to $360 a month there, a little more during the holiday season.

“The first thing I bought in the commissary was tweezers,” Okun says. “I’m like, ‘I’m not letting these eyebrows go crazy in here.’” The commissary forms the basis of the prison economy; black market goods and services—such as massages, manicures, and clothes pressing—are widely available by bartering items purchased at the commissary. (Tins of mackerel have especially high value among the protein-obsessed weightlifting crowd.) “It cost me a bag of pork rinds to get my hair cut,” Okun says. If you can’t live without All Things Considered, cheap AM/FM radios and MP3 players are also available. (The prison system has its own iTunes-style store, where songs cost between 80 cents and $1.55.)

But What Are the Bathrooms Like?

Don’t be embarrassed: Our experts reveal that logistical questions about the, ahem, accommodations in prison are at the top of most clients’ list. That said, on this most private of matters we will leave the details to your meeting with your consultant.

Live Your Best Life

Few campers will enjoy their incarceration, but it’s a time that naturally lends itself to self-improvement and planning. Internet access is forbidden, as is social media (those Michael Cohen tweets “were likely e-mailed out through corrlinks.com, the monitored prison e-mail system, to an outside contact who posted them,” Zoukis says).

This means there’s ample time to hit the gym. Though free weights have been banned in many prisons because of their potential to be used as weapons, elliptical machines, walking tracks, and an assortment of inmate-led classes, from Pilates to Sweatin’ to the Oldies, are available at most camps. “It was really amazing to see some women who might have been a little overweight start walking on the track, and within months they’d have lost weight and be running,” Okun says.

Though it’s against the rules to conduct business inside, white collar inmates often begin preparing for a new life in which they are banned from their former industries. Okun became friendly with a doctor sent away for prescription fraud who was training in cosmetology so she could open a salon.

Chong was the rare bird who thoroughly enjoyed his entire time away. “I tell you, it was probably one of the most exciting times in my life,” he says. He founded a sunset watching club, tangoed with bikers, studied the I Ching, and began frequenting the prison’s sweat lodge, a common feature at institutions with significant Native American populations.

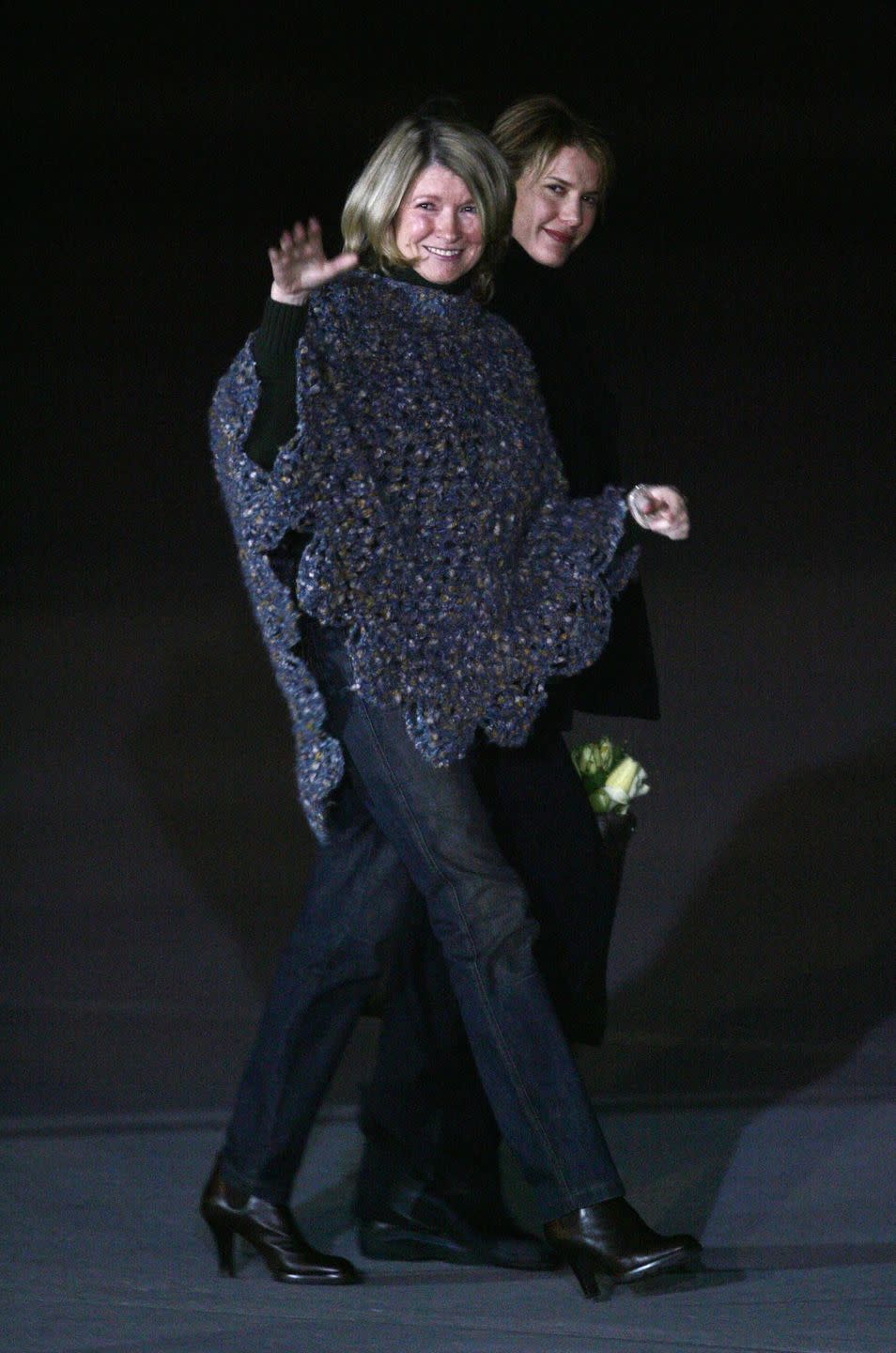

Chong found that the dirt around Taft Correctional Institute was rich in clay, and it was so plentiful that he even built a kiln next to the sweat lodge to fire his creations. “I made bongs,” he says. During her time at Alderson, Martha Stewart famously molded an entire crèche from clay.

The Worst May Already Be Over

Understand that the bleakest part of your prison experience may come before you even set foot inside. “Before I went to Alderson, I got very depressed and stayed indoors,” says Okun, whose jewel theft case was tabloid catnip. From her first appearance in court until she reported to Alderson, New York Post photographers followed her, staking out her $4 million home in Darien, Connecticut.

“One time I went to the Starbucks in Darien, and people were staring at me and pointing,” she says. “I can’t express the level of hurt you feel. Not for yourself but for how it’s affected all of your loved ones.”

Okun advises clients to resist the temptation to read anything about themselves in the period before they go in. “I think anybody who has ever been through it would agree that pre-surrendering, pre-prison time is the worst, mentally,” Scruggs says.

“From the time I pleaded guilty until I actually showed up at the prison, I don’t think I got a good night’s sleep. It was just the disgrace of the whole thing. It’s like a big blanket on you the whole time. Once I got to prison, it actually got better.”

This story appears in the October 2019 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like