I'd Made an Uneasy Peace With My Job As a Sommelier. Then I Lost My Sense of Smell.

I lost my sense of smell for maybe five or six days in May. Ostensibly, it was a symptom of contracting COVID-19, though I wasn’t tested, as I wasn’t terribly sick beyond a fever and fatigue. This total blackout of smell was unlike anything I’d ever experienced; it took only twelve hours to set in. I confirmed it by running my fingers through the herbs I have growing in small pots, then lifting my hands to my face and smelling. I do this fairly often, proud I can keep these aromatics alive in the grimy circumstances of a Brooklyn windowsill. When I did so, I realized I couldn’t smell a single herb—not my lemon thyme, oregano, not the sage nor dill, usually so distinct and sweet. The moment cut me. I thought: to live without being able to smell things that grow?

A day later, I underlined the loss by opening a bottle of Skerlj’s Malvasia. It’s a favorite wine of mine from Friuli, usually tropical, splashy, and brusque with acidity. I couldn’t sense any of the big florals, citrus, and saline aromas I have more or less memorized on this wine. It was disorienting. I didn’t drink more than an ounce, as the fruit on the palate also flattened entirely. I found myself thinking for days about what it would be like if this were permanent loss, if herbs or coffee disappeared from my life—if wine did.

I’ve always been conflicted about working with wine, earning my keep by selling and talking about it in restaurants. For nearly fifteen years, wine has been a regular source of joy and learning. But it’s difficult to witness the ways in which our culture pushes everything joyful through the meat grinder of commodity. It is hard to focus more on P&L reports for restaurants than on the nuances of history and lore, viticulture, fermentation. Largely I have accepted this as the price I pay to do a job I otherwise like a great deal; I turn myself into a commodity for a business owner, as someone who has skill in making profit off a desirable object. I walk away with a paycheck and regular access to things of beauty.

But with the loss of smell, the temporary loss of the ability to sense wine altogether, and perhaps with it a job, I was reminded, sharply, that our culture does not teach us what is important outside of the practice of amassing wealth and fancy goods. Or at least, it’s not a lesson taught prominently. And even after the pandemic exposed again all the intense economic imbalances involved with wine and restaurants, I don’t know that our culture will agree to relinquish the tight connection between money and wine.

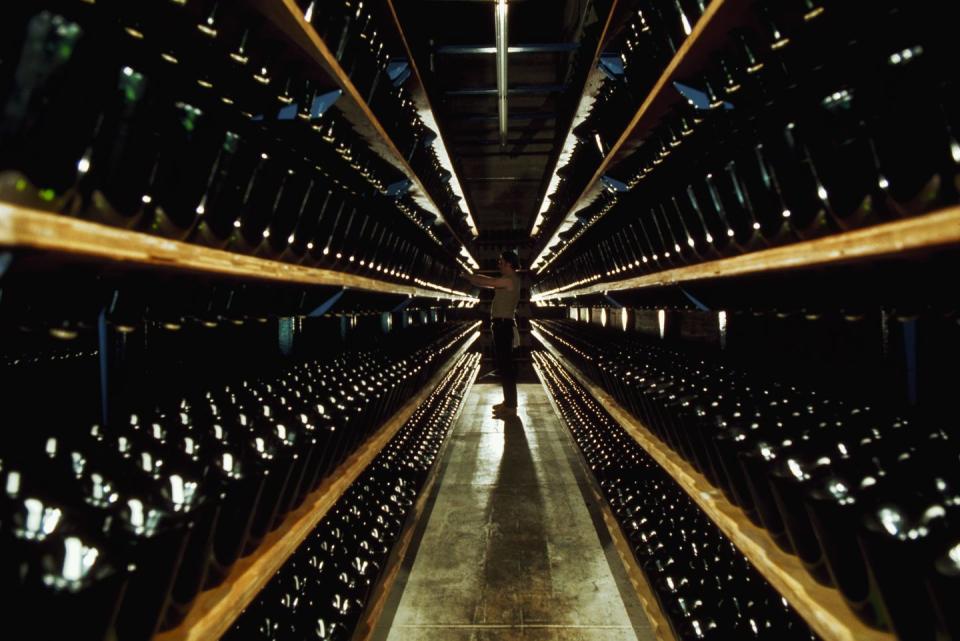

I am thinking of wine collectors now, those older men (always men, white, middle-aged or older) who come knocking on the doors of a certain echelon of restaurants to consign or sell their collections. I’ve worked in restaurants where collectors are important investors; this means you’re more or less obligated to offer their collections on your list. For many years in New York, at least, the fanciest wine lists in town were built off private cellars. Collectors hope to make a little profit off turning their blue-chip, allocated cellars. I believe they do this simply out of a desire to feel cool—to be knowledgeable and savvy, like men who can make money betting on baseball or boxing. The second case is older people who have gathered so much wine over their lives they now need to sell it. They simply can’t drink what they have, so they may as well make some money on it. I feel a certain dull sadness at these men: Having thrown piles of exquisite yams into their silos for decades, the yams at the bottom of the silo are beginning to rot. Granted, wine rots more slowly than regular yams, but rot it will.

I suppose this is one of the reasons wine brings me so much pleasure: Once you get to know it pretty well, you see it interact in time, with time, in a prismatic, surreal, and sparkling way. Your 2017 Burgenland Cabernet Franc rosé—himmel auf erden—was very good last year. But one year forward and it shows fresher, more complete. (You at 35, say, are even more resolute than you were at 34.) Three years more, perhaps, and one might guess the rosé will emerge harmonious, magic, bearing a rocky garden of berries and spice. (Maybe I will be my most beautiful at 40.) And wine has even tinier movements in time than those. On first opening, a wine tastes like this; an hour later, like this, and sometimes eight hours later or even the next day, the wine pops open like a peony; it reveals thirty new petals neatly tucked inside that you couldn’t see moments before.

Amazing: Here is another living thing splicing itself into time, reaching out from somebody else’s fields and cellars hundreds or thousands of miles away, saying: Watch—listen—see me before I go. And they do go. Wait 24 hours sometimes, and their beauty has passed. There are certain flowers that do this, too, bloom for a day and then die. Beauty changes quickly. Anyone who has children knows people are like this.

My sense of smell came back after nearly a week. I ran my hands through my herbs again, as I did every day, to determine if it had returned. When it did—the smell of sage!—I felt this pang of relief and joy. Smell, and its handmaiden taste, has an incredible capacity to both ground us in our bodily reality and to open an immediate channel to memory, to powerful feeling. What a privilege. I thought to myself: If I didn’t have access to this sense, if the loss were permanent, definitely I would stop working with wine. The beauty would be overshadowed by the frustrating commodity-trading aspect of wine work that is necessary under our current capitalist condition. We recognize correctly it has inherent value, so we assign a dollar amount to it. This isn’t so out-of-line; after all, it is a discrete object, albeit a slippery one, full of this time-interrupting, time-contingent quality. What seems so foolish to me is what happens when we apply our wealth-piling obsession to this thing that exists in a crux between the agricultural and the aesthetic. Pile up the yams, quibble about their value, see how many wealthy people you can convince they are worth an ever-escalating price. In the meantime, miss the revelation of beauty. I am exhausted by this pursuit.

I’d like to believe, in the wake of a global health catastrophe, that it is possible to reorient our attention away from hoarding wealth and back toward experiencing, sitting with beauty, sharing it. Obviously money buys lots of experiences, which is why wine people like me are employed. You need resources too to make genuinely beautiful things, but I would suggest you don’t need that many resources, that our sense of scale is radically askew. I'd like to believe it’s possible to deliberately redistribute resources across classes, races, nationalities, so that lovely things are more available to all. The wine and restaurant industries know this already to some degree; we’ve seen the shift away from Napa Valley corporate money and Manhattan’s high-end restaurants, back to the vineyard, back to the rough-hewn table.

I just don’t know that—even after we’ve witnessed plainly how barely workable restaurants are, and how vulnerable many workers in them are, because they’re paid a pittance, with many being immigrants ineligible for state aid—we will relinquish absurd restaurants that operate as pageantry for the wealthy and treasure houses for the rarest bottles. I don’t know how to resolve this ugly binding together of things of beauty and capital.

Here is what does not exhaust me. A month before the pandemic broke out, I sat on a tiny stool in my friend’s apartment, staring at the blue, gray, and red stone floor, worn from a hundred years of use. My friend spoke French with a visiting Loire vigneron; another young writer in town joined also; it was good company. Though I don’t speak French, I mostly followed the talk about a new vineyard being worked. We drank Gérard’s Chenin Blanc from this new parcel; it was pure, balanced, free of botrytis but with a similar ripeness: Loire Valley shoulders warm with sun. Gérard watched me taste the wine under bushy eyebrows. I told him, I love it. He smiled, one crooked tooth showing.

The evening darkened, conversation continued, the room turned blue. We drank the wine quickly; it was too good to last long. But the wine did its work, it warmed me, and it sealed a small increment of time. The wine speaks: I am here, I was nurtured into existence, I am the work of hands and Earth and the sun—I am yours, all of you share me. So we took a small and informal communion together that only lasted the span of an hour. This does not tire me; this is a different value, the real value. In that room, very little wealth was required or exchanged. This is what I have been storing in my silo. I am certain that it does not rot or decay.

You Might Also Like