Ian Bridges Had Cancer 3 Times. He Lived to See a Breakthrough

This story is part of The 2020 Project, a Men's Health special project that explores the lives of 20 different 20-year-old men across America. To learn more about the others, go here.

IAN BRIDGES was stick welding a quarter-inch steel plate at Green River College in Auburn, Washington, when a sneeze sparked a nagging, achy pain in his back. Just like any normal person would, he thought he had pulled a muscle or something. But by this point, very little about Bridges’s medical history was normal.

For the next two days, he applied ice and heat. “It kept getting worse, to the point that when I sat down in my chair, whenever I sneezed, it felt like someone was driving a knife into my vertebrae,” he says. On February 14, 2019, Bridges got a blood test that confirmed his suspicions. For the third time in his life, he was diagnosed with the same cancer: The acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) had returned.

Having been through treatment twice before, Bridges knew that each time he was diagnosed with ALL, his chances of achieving remission decreased. At that moment, he had only one thought. “Please pardon my French, but I’m thinking, Fuck me.”

Still, it had been more than a decade since he had become one of the nearly 16,000 children in the U. S. who are diagnosed every year with some form of cancer and who face varying survival rates. Over the past few generations, the quantum leaps made in how to treat and cure these patients has contributed to a 60 percent decline in childhood-cancer-mortality rates. There are thousands of kids alive right now who, if born in a different era, wouldn’t be.

Bridges is one of them, and not only had he survived ALL twice, but he’d done so for long enough that doctors had another treatment option to help him in his third battle with the disease. It involved an experimental trial about 30 miles away at Seattle Children’s Hospital. They had spots for 28 people total.

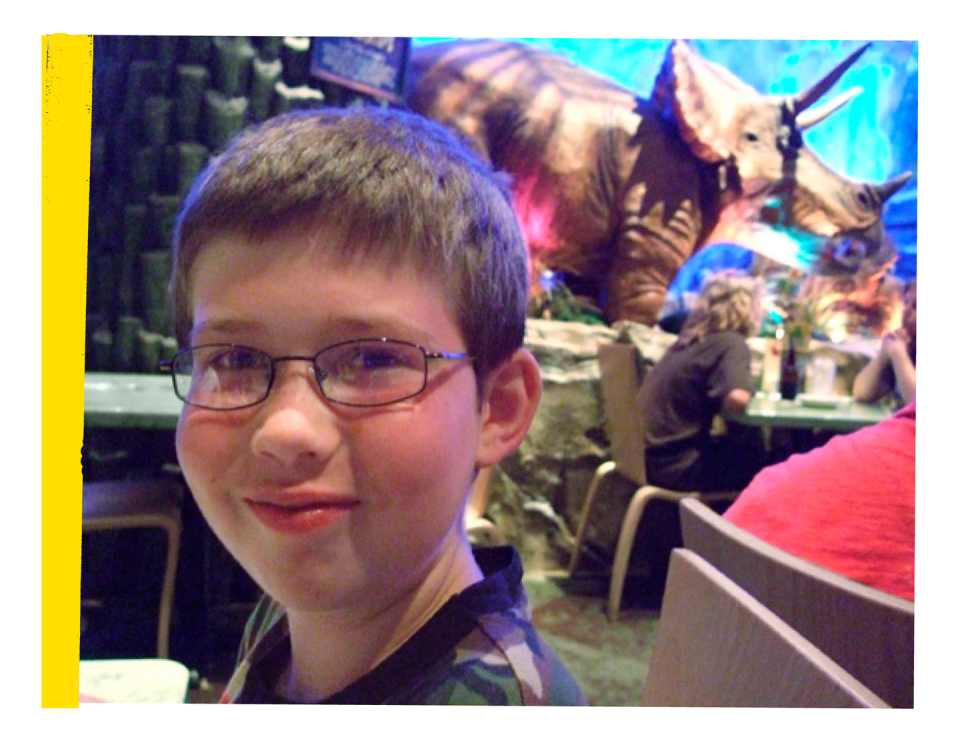

GROWING UP in Maple Valley, Washington, Bridges was passionate about dinosaurs and wild animals. His mother, JoAnne, recalls that her son’s extensive knowledge often led him to correct museum curators as they spoke. “He’s always been really inquisitive and likes to research things,” she says.

He’d also joke around by crawling about on all fours like a polar bear, but in 2008, when Bridges was eight years old, his lower back started aching. His parents took him to a chiropractor, but the pain persisted. They saw a pediatrician who suggested that Bridges was simply experiencing growing pains. The ache increased to the point that one day JoAnne decided to take him to urgent care, where he had some blood tests. Abnormalities in the blood work sent them to an oncologist for more-specialized testing. “I kind of knew what was going to happen, because I had done enough research,” she says. “When the doctor came in and said he had leukemia, I was like, Okay, what do we do now?”

Initially, Bridges didn’t understand the gravity of his diagnosis. He thought he was going into the hospital for something like a periodic tune-up, with free movies and plenty of time to lie around as new fluids dripped in.

Leukemia is a cancer of the blood caused by an error occurring during the transformation of cells in the bone marrow. Bridges had B-cell ALL. ALL is the most common cancer in children, and B-cell is the most common form of ALL. B cells are part of the immune system responsible for making antibodies. In Bridges’s case, his leukemia sprang from a cell malfunction causing the cell to continuously grow. This can lead to pressure in the bone marrow, causing aches and pain.

If left untreated, leukemia can result in organ damage and death. But Bridges was in the standard-risk group for patients with B-cell ALL. His chances of being cured were about 80 to 90 percent. Over the next three years, he endured several three- to four-day rounds of chemotherapy each month. That’s the widely effective general treatment, although there are plenty of side effects: Bridges felt exhausted, nervous, and nauseated, and he suffered balance problems, not to mention hair loss, the source of some dark humor. “I could pull at my hair very lightly and I could pull out, like, clumps of it,” he says. “I used to do it as a party trick to people.”

He barely attended school. When he did, he recalls that other third graders liked to stare at the bald kid. Bridges became anxious about how each hospital visit would make him feel, but through it all he never doubted that he’d survive. And he was right: By age 11, his cancer had gone into remission, and he was back to playing video games like World of Warcraft, hanging with friends, and helping his dad organize his tools for handyman projects. He never imagined that the cancer might return.

A year and a half later, a routine blood test read differently. “He was angry,” his mom says. “He went into his room and shut the door and was like, Well, if it’s back, I might as well just give up now because they’re not going to be able to cure it.”

Bridges says he went through all five stages of grief in five minutes and arrived at a conclusion: He could die this time, but first he would have to live as a miserable cancer patient.

THIS TIME, Bridges was much more aware of his prognosis and the treatment he would have to endure. Although he experienced less physical pain, the mental toll was much greater. And the survival rate for someone in his circumstances didn’t help. Rebecca A. Gardner, M.D., who specializes in pediatric oncology at Seattle Children’s Hospital, says that given the recurrence, Bridges’s odds of surviving with treatment were more like 60 to 70 percent. When a relapse occurs, a patient’s cells have already been exposed to the chemo drugs and are more likely to resist their effects; this is called chemoresistance.

As Bridges saw it, he was no longer a kid facing a bright future but a person on the verge of dying. To rid his body of leukemia, doctors gave him the same treatment as before with a higher intensity of chemotherapy. The treatment ravaged his body, causing his platelet levels to drop to almost 20,000 per microliter of blood. (The normal range is 150,000 to 450,000.) “I [felt] like a corpse that was pulled out of a river,” he says.

But the thing is, it worked—again. By the time he was 15, he’d entered into another remission period. He felt reenergized and went to high school, attending dances and building stage sets for the theater department. He honed his shop skills, and in ninth grade he welded a handmade outdoor grill that his family still uses. During his senior year, he made cell phone stands and, as part of a school project, created a me morial sign for the Tahoma National Cemetery. His next step was community college, where he continued with his interest in becoming a welder.

WHEN BRIDGES arrived at Seattle Children’s Hospital after his third diagnosis, most of the kids in his trial were younger. It was like joining a precarious club: Kids who are repeatedly diagnosed with cancer face -diminishing odds of survival. With each new round of treatment, five-year survival rates decrease and the chances of being chemo-resistant increase.

The experimental treatment at Seattle Children’s Hospital was Bridges’s best option. He may have felt helpless when his cancer returned for the second time, but the potential of this new treatment was empowering. “In my mind it was like I didn’t really have much of a choice, because it was like, if this can, you know, get rid of [my leukemia] forever, I was like, Sign me up,” he says.

In April 2019, Bridges and his mother moved into the Ronald McDonald House in Seattle, where he enrolled in the fifth trial of pediatric leukemia adoptive therapy (PLAT-05). The plan was to use patients’ own infection--fighting cells, called T cells, to rid their bodies of leukemia.

This general concept has been studied by scientists for decades. In recent years, cancer researchers at Stanford and the National Cancer Institute have launched their own trial. Seattle Children’s Hospital began its T-cell immunotherapy work in 2012, and so far more than 200 patients have been treated with similar immunotherapies by the hospital. For patients with ALL, the treatment currently has a 90 percent remission rate.

The doctors start by using a machine that draws out a few pints of blood, extracts the cells, and pumps the remaining blood back into the body. Those cells are brought to a lab, where the T cells are removed and then reengineered for a specialized attack. The new T cells’ chimeric antigen receptors are weaponized so that when they are infused into a patient’s bloodstream, they seek out proteins expressed by leukemia cells and destroy them.

It also hurts a lot. To extract Bridges’s T cells, the doctors used a procedure called apheresis. This involves inserting a catheter into the neck to draw out the blood. “I felt like some cyborg reject from Star Wars,” he says.

Dr. Gardner, who is the principal investigator for the PLAT-05 trial design, says many patients begin to feel fever-like symptoms after receiving their newly engineered T cells. This is a sign that the treatment is working. It takes as little as a few weeks to see remission, but because B-cell ALL originates in the bone marrow, there was one last hedge: Bridges could opt for a bone-marrow transplant.

His preparation for the transplant involved twice-a-day blasts of full-body radiation for three days straight, followed by two days of chemo-therapy to destroy his current store of marrow so that it could be replaced with donor marrow. There was no guarantee it wouldn’t be rejected.

ON OCTOBER 31, 2019, Bridges left Seattle and returned home to Maple Valley.

He was in remission. All told, 85 percent of the patients in his PLAT-05 trial fared the same. “It very much put, like, a new perspective on things,” he says. “It allowed me to see firsthand what I think the future of cancer treatment is going to be.”

Since Bridges’s treatment, Seattle Children’s Hospital has continued to improve its therapy, with doctors targeting a new receptor that should prevent patients’ bodies from rejecting the treatment. “I think our blue-sky idea is that ultimately we can use this type of therapy or similar types of therapy to really replace all the chemo-therapy that kids get,” says Dr. Gardner.

That milestone may be as close as ten years away—roughly the same number of years that Bridges has been fighting. For now, he’s got just one major limitation: no more welding, at least not as a career. His doctors would rather he not complicate his health by inhaling metal dust or residual gas regularly.

For a while, Bridges felt listless. Then, on a recent trip to the Fort Walla Walla history museum, he befriended a tour guide who gave him several historical artifacts that he decided to research a little deeper. This fall, Bridges has been taking paleontology and anthropology classes at Green River College.

In some ways, it feels like being a kid again—the more he learns, the less likely he is to dwell on his past, even if he still gets monthly blood tests. “If I’m going to do something with my life . . . I can’t let myself think about that,” he says. Someday he envisions himself as an archaeological field assistant or a museum worker, but he has yet to decide.

He has time. It’s a new feeling.

You Might Also Like