Houston's Museum of Fine Arts Is Proof That Everything Really Is Bigger In Texas

For the better part of the last decade, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has been in the midst of an ambitious expansion, which, with its $475 million price tag, is currently the largest cultural construction endeavor in North America. This month it finally comes to an end with the debut of the Kinder Building, the last piece of a 14-acre puzzle that makes MFAH the fourth-largest museum in the country.

The Kinder Building, named in honor of Nancy and Rich Kinder, who spearheaded the fundraising efforts, will serve as the new home of the museum’s extensive collection of modern and contemporary art, a trove that has grown drastically thanks to the late philanthropist Caroline Wiess Law, who, upon her death in 2004, left a majority of her estate to MFAH, specifically to finance the acquisition of 20th- and 21st-century art.

“For the last 13 years we’ve been spending more money on modern and contemporary art than almost any museum in the country,” says MFAH director Gary Tinterow. “The need for more space became evident.”

In 2012 the museum launched a competition to find the right architect for its grand ambition. Steven Holl, the man behind the Kennedy Center’s REACH expansion in 2019, won by unanimous vote. First, he was the only one to propose putting all parking underground so as not to use up acreage on lots. Then he recommended erecting a new, larger building for the museum’s Glassell School of Art (completed in 2018), thereby expanding the sculpture garden designed by Isamu Noguchi. “I said it would be a little bit bigger than Dallas’s sculpture garden,” Holl says. “I think that’s what got them.”

MFAH’s first exhibition building, which opened in 1924, was a neoclassical work later added to by modernist icon Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The second building, which opened in 2000, is a limestone structure by Spanish architect Rafael Moneo. For the Kinder Building, Holl aimed for a complementary contrast. His 237,000-square-foot translucent glass construction features terrazzo details and a curve used by Mies in the original building, while its striking rhomboid shape corresponds to the street edges. The ceiling’s concave curves bring in natural light, and the entire building is clad in hollow glass tubes that trap hot air, creating a natural cooling effect.

And, yes, the building is made for a post-pandemic world: no elevators, good air circulation, and an abundance of outdoor space. It is surrounded by reflecting pools, fountains, oak trees, and courtyards. “You have this feeling of porosity,” Holl says. “It brings the landscape in.”

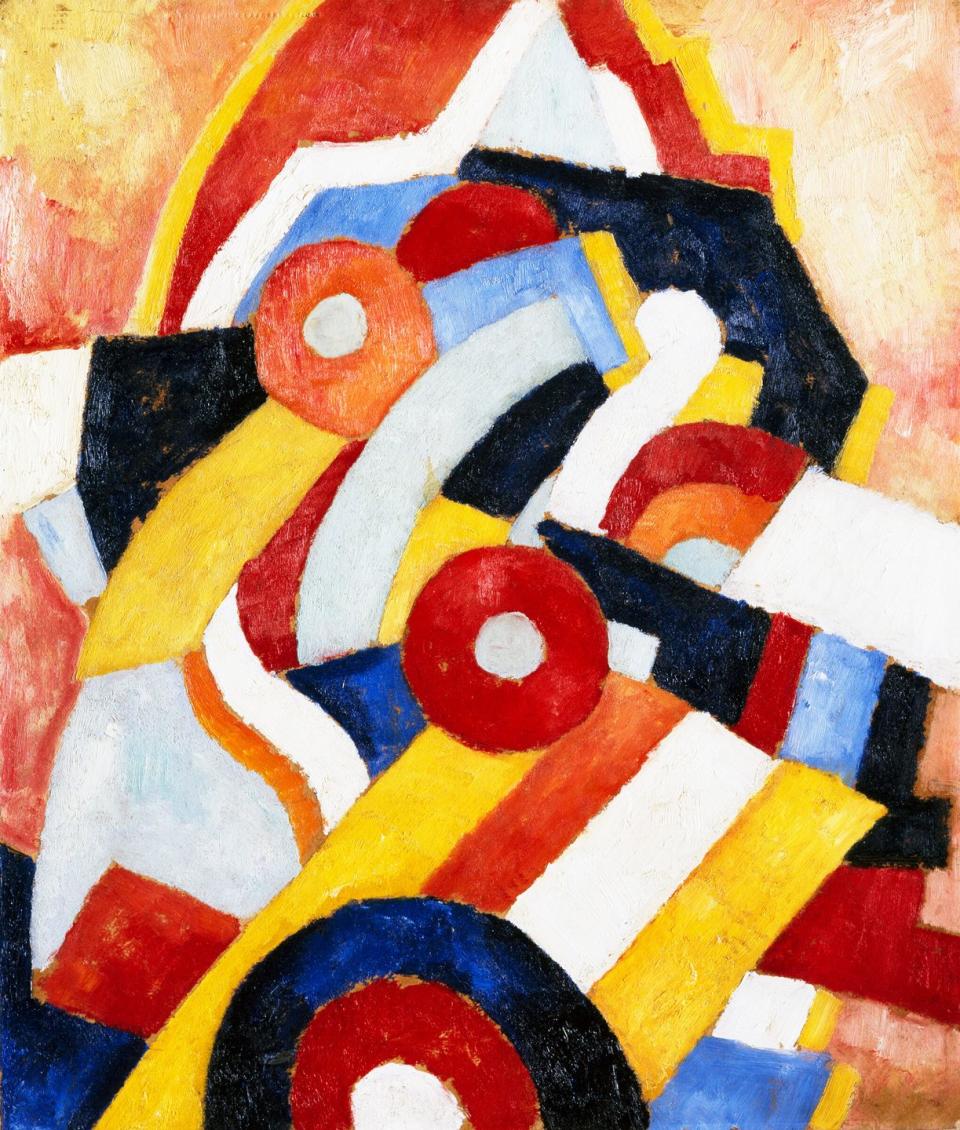

The Kinder Building’s inaugural installation will feature an array of MFAH’s modern treasures (Picasso, Matisse, Rothko, Brancusi) as well as several exclusive commissions, including a tapestry by El Anatsui, a bamboo and silk dragon sculpture by Ai Wei Wei, a new installation by James Turrell, and what will be the most comprehensive display of Latin American modernism in North America.

“With this new building, we’re making a pitch for being the fourth art destination in the country after New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago,” Tinterow says. It marks how far the city of Houston has come in less than a century; when MFAH opened, in 1924, it was the first art museum in Texas. “We’ve come full circle,” Tinterow says.

This story appears in the November 2020 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like