A History Of The Invisible Mississippi Delta Chinese Community

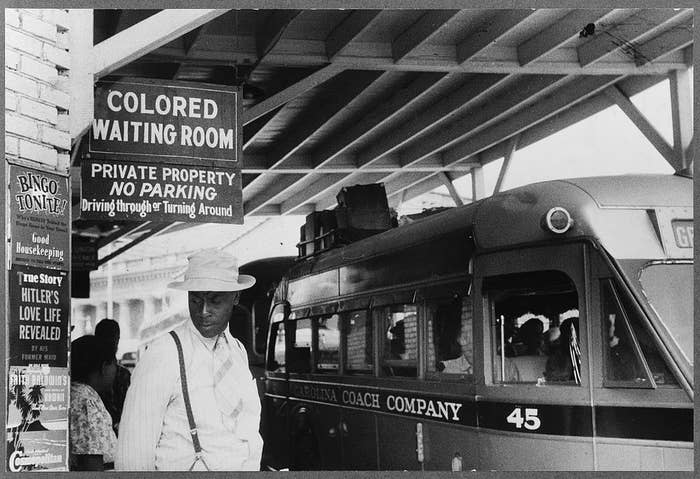

The story of the Jim Crow era, as popularly told in our media and classrooms, is predominantly told as that of a sociopolitical battle fought by Black Americans against the state of second-class citizenship imposed upon them by white Southern institutions and society. This understanding of history is as black-and-white as the distinction drawn by segregationist institutions between Black and white.

But we can’t accept that interpretation. It makes many groups outside those two racial categories either irrelevant or invisible in the story of segregation and civil rights. And it means we miss the unique ways those groups contended with a strict racial hierarchy.

One such group with an unusual story to tell is the Chinese community in the Mississippi Delta, which, despite its diminutive size, once presented a massive challenge to the coherence of segregation in the South. The story of Chinese immigrants to the region began almost immediately after the Civil War and the emancipation of slaves.

Many of the first immigrants were sojourners, who were sending their earnings back to their families across the ocean and eventually planning to return to China.

Thousands of Chinese workers were already involved in farming and railroad construction in the west. They grew a reputation for cheap, reliable labor among farm owners and business companies, and they were viewed by cotton plantation owners as an ideal replacement for slaves.

The offer of employment in the south coincided with a rise in anti-Chinese violence and scapegoating for the economic depression that hit the western states in the 1870s.

Pressured to leave profitable jobs in the west by both state measures and mob violence, many Chinese sojourners moved to other states providing work and more tolerance for their presence. They didn’t find cotton picking the profitable job they hoped for. And the plantation owners didn’t find the Chinese sojourners to be the exploitable, cheap labor they were hoping for. Disputes over lack of pay for plantation work led the Chinese workers to open their own businesses. Most frequently, these were grocery stores.

Part of the reason they chose grocery stores, in particular, was a significant change in their situation as a result of US national policy. Racist attitudes against Chinese workers in the wake of the depression reached a fever pitch in 1882 when Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting the entry of Chinese workers for 10 years and barring them from naturalization. This development led many sojourners already in the country to reconsider their plans for working in the US. However, the act specifically allowed those classified as merchants to bring their families over from China. Being a grocer was an occupation classified as a merchant. And thus, from 1903 to 1925, that was the job of choice for over half of the Chinese immigrants of the Mississippi Delta.

Grocery stores also provided the Chinese immigrants a unique opportunity to create a space for themselves in a segregated society. By the early 1900s, cotton production was becoming increasingly mechanized. This process reduced the need for the labor of Black sharecroppers on the plantations, which led the plantation owners to close the facilities they’d used to keep the sharecroppers tied to the land they worked. Specifically, the plantation-owned and -operated commissaries, which had been the sharecroppers’ main source of food, clothes, and farming supplies. Meanwhile, white-owned grocery stores were often unwilling to serve Black customers.

Chinese grocers, by virtue of having the same hostility shown to them in white neighborhoods, opened their stores in Black neighborhoods in the towns of the Mississippi Delta. At first glance, the Chinese grocery store simply fulfilled the need for a supplier of essential goods for the Black community. However, the relationship deepened over a shared experience of discrimination under segregation. Chinese grocers were well acquainted with the treatment people classified as “colored” received, and were on the whole, friendlier to their Black customers than white grocers. For instance, they didn’t require deferential acts of courtesy often demanded by white business owners. Chinese grocery stores also lent themselves to being spaces for passing the time and chatting with other members of the community.

In fact, these grocery stores became a rare hub of racial integration in the South. In towns like Yazoo City, white land and business owners would visit the grocery store to hire hands. And working-class white customers would be able to inhabit the same space, at the same time, as Black customers. By virtue of not having a defined place in the Jim Crow system, Chinese immigrants inadvertently created a space that, at least temporarily, existed outside its strict rules of separation.

But Black and Chinese relations went further than mere coexistence. Chinese grocers assisted Black customers with Social Security forms and, on occasion, posting bond. Bonnie C. Lew, who was second generation and whose family moved to the Mississippi Delta in the 1950s, recalled that her mother would sign over a million welfare checks for illiterate customers for a dime each signature. Chinese grocers also extended credit more frequently than white-owned stores did, which gave Black workers a cushion against an unfavorable employment market. And thus, over the course of the early 20th century, Chinese immigrants gained the trust of and became intertwined with the Black community in Mississippi.

As a natural consequence of the deepening relationship between the two groups, interracial couples emerged — an uncommon but significant development under the rule of Jim Crow. The trend of sojourning meant that the majority of Chinese immigrants in the south were male, with as many as eight per every female in some decades. Some men, even those with families and wives back in China, started relationships with Black women; however, they never amounted to more than 20% of the Chinese population in Mississippi at any time. Interracial children among these couples were even rarer, amounting to less than 5% of the Chinese population by 1946.

However, the relationship between the Black and Chinese communities never deepened any further after the 1920s. In fact, the opposite occurred and the Chinese people of the Mississippi Delta would make it an informal rule to create as much distance from their Black neighbors as possible. The sudden turn from integration wasn’t the result of any incidents of animosity; rather, it was a development demanded by white society. In return for shunning ties to the Black community, the white community was prepared to reclassify Chinese Americans in the racial hierarchy of Jim Crow.

For much of the period before World War II, the white community had been content to group Chinese immigrants with the Black community and flat out ignore that their Chinese ethnicity existed. For context, the Chinese population was tiny, with Mississippi — the state with the largest concentration of Chinese immigrants in the South — only counting 174 in 1910 and 211 in 1920 in its census. And they were mainly based in the towns of Washington, Coahoma, and Bolivar Counties.

Ah Quon McElrath, a retired labor organizer and second generation, demonstrated the invisibility Chinese Americans experienced as she recalled an incident from her time working in the South during the 1930s: “I remember going to see the sheriff in Green County, and there are two Black women, three Black men with me, and we told them what we were about. He just couldn’t make out what I was. He looked at me. I’m not white, I’m not Black, so what the hell am I? And so when I said I was from Hawaii, oh, that broke the ice. ‘You’re a hula-hula girl,’ he said.”

But as invisible as the Chinese immigrants were, they weren’t exempt from the brutalities and injustices of the racist system they lived under. They were routinely subjected to “unfair wages, race-based taxes, race-based lynching, and general treatment as disposable labor.” The white community also barred Chinese immigrants from social organizations, country clubs, fraternal groups, recreational activities, and, most importantly, white public schools.

By the 1920s, the policy of exclusion had become an exigent problem for Chinese grocers who managed to bring their families over from China. Due to their grouping in the “colored” caste of the Jim Crow system, Chinese children were forced to attend whatever schools existed for Black children. Despite the logic of “separate but equal,” established by Plessy v. Ferguson, requiring that the separate facilities be comparative in quality, the reality was that “colored” public schools just didn’t exist.

Before the 1930s, the education of Black children was handled informally and most of it was funded by private contributions. Even when public schools for Black children were opened, starting in 1935, they received paltry funding from the state. In 1941, Bolivar County spent $238,161 for the education of 6,216 white children but only $38,765 for 35,708 Black children. That’s the kind of public education the Lum family was unwilling to accept when it started fighting what would become the Supreme Court case Lum v. Rice in 1927.

Martha and Berda Lum, the daughters of two Chinese immigrants, had attended white schools until the Lum family moved to Rosedale in Bolivar County. In 1924, they were told to leave and attend the Black school in town. The Lum family brought up a case against the school district’s board of trustees to keep Martha in the white school. The prosecution employed a strategy that didn’t argue against the principle of segregation but rather against the lack of consideration for a third race that wasn’t Black or white.

When the case reached the circuit court, the Lum family’s lawyers stated that Martha “is not a member of the colored race nor is she of mixed blood, but that she is pure Chinese...There is no school maintained in the District for the education of children of Chinese descent.” On the basis that she was neither colored nor white, there hadn’t been facilities provided for her, as a Chinese person, which went against the principle of “separate but equal.”

The circuit court was in agreement with the prosecution. The case was then appealed to the state supreme court, which overruled the previous decision by asserting that Chinese people were not “white” and thus had to be “colored.” The United States Supreme Court ultimately sided with this argument, stating, "The decision is within the discretion of the state in regulating its public schools."

The ruling in Lum v. Rice empowered schools to discriminate specifically on race and would serve among other cases to block the desegregation of education until the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954. But immediately for the Chinese Americans in Mississippi, it ended any hope of carving a defined space for themselves in the Jim Crow system. They saw that there could only be a first-class white population and a second-class colored one. Some Chinese families, seeing the writing on the wall, left the Delta in search of any school that would allow exceptions. The Lum family was among them, eventually finding a school in Arkansas.

For those who remained, their best means of securing the admission of their children to white schools was bending to the demands of white society. And the chief condition for that access was to cut ties with the Black community. According to David L. Cohn, author of Where I Was Born and Raised, the white community feared that if Chinese children were allowed to attend white schools, then eventually children of a Black parent and a Chinese parent would also attend.

The strict biracial logic of Jim Crow, where someone was either Black or white, placed great emphasis on the supposed "purity" of a person’s race. Just the hint of Black ancestry was considered enough to classify a person as Black. Accordingly, the admission of an interracial child meant the admission of a Black child. The Jim Crow system couldn’t tolerate even a minor step toward the social acceptance of Black people in a white space. And so, white society and the Chinese community made an effort to completely eliminate interracial relationships.

Leaders of the Chinese community pressured Chinese men to end their relationships with Black women and to even abandon their interracial children. Those who refused would be isolated and left with no support system. In one example, Wing On, a Chinese man, and Emma Clay, a Black woman, had 13 children and all of them were shunned by the white, Black, and Chinese communities. The ostracization they experienced would follow them no matter where they went in Mississippi or whom they married. Chinese leaders went so far as to send away a child who had only Black friends and no white ones.

In other cases, more coercive measures were used to force interracial families to leave the region. Grocers would conspire with a wholesaler to drop a grocery belonging to an interracial family. That family — cut off from supplier, money lenders, and people to talk to — would eventually have to leave. Another interracial couple in Cleveland, Joe Chow and Hazel Taylor, married in 1933 and were harassed by police. When their child was born, Hazel notably started working at a second grocery in Greenville while Joe remained in Cleveland. The couple eventually left the state after one of their shops burned down. By the 1940s, there were no more formal or informal marriages between Black and Chinese Americans in Cleveland.

At the same time, new laws were passed to allow Chinese children to attend white schools. Anti-Chinese sentiment in the region cooled, as it did across the nation as a result of the alliance between the US and China in World War II. But an improving image among the white community in Mississippi constantly required further distancing from the Black community. And white institutions still rigorously divided Chinese Americans into categories of “pure” and “mixed.”

From then on, the Chinese community strove to erase any evidence of past interactions with the Black neighbors they lived with. Children were given lessons on correct grammar and enunciation to train them out of accents they’d picked up from Black friends. Instead, white customs were adopted enthusiastically. Mealtime would feature buffet lines with fried chicken and potato chips. Traditional Southern white names like Coleman and Patricia were used. And if Chinese children weren’t allowed into white schools, they’d be educated at home or work in the grocery. They’d be made to do anything but attend Black schools.

For their efforts, Chinese Americans were admitted into more and more white institutions and given a special status in white society — one carefully extended only to those considered "pure." Following the end of segregation, Chinese Americans in the Mississippi Delta were nearly equal in status to white Americans.

Just as Chinese efforts to assimilate into white society helped the Chinese population gain access to white social resources, so did they play into white society’s objective to reinforce white supremacy over Black Americans. One notable trend the white community latched onto was the control the Chinese community exerted on its youngest members in discouraging them from associating with Black Americans. This was a source of pride that was used to emphasize the “low delinquency rate” among Chinese Americans. The white community parroted them and spoke as well of the success of the Chinese community, tying a vague metric of crime to a pattern of interactions with Black people. Here we find the origins of the “model minority” myth.

Even though the basis of Chinese American success was entirely tied to how well they served white interests, white society still touted it to deliberately downplay the role racism had on the systemic issues facing non-white minority groups, particularly Black Americans. The white community could claim that whereas Black Americans struggled, Chinese Americans thrived. It created the deceiving perception that the issues were the fault of Black Americans, not decades of segregation and discriminatory policies.

What’s particularly ironic about this is how contrary it is to the material reality facing the Chinese community of the Mississippi Delta. In estimates within the community, the population peaked at around 2,500 in the 1970s and shrunk down to around 500 in 2017. Their economic prospects as grocers declined during that time as they lost the special niche they filled in the Black community. More grocery stores, especially large chain stores, opened up in the area, which took away many Black customers. Families packed up and left to find new economic opportunities.

Meanwhile, children left to other parts of the country for higher education, not content to inherit the old grocery store from their parents. As a result, the Chinese community in the Mississippi Delta is almost gone, even as Asian Americans as a whole are the fastest-growing demographic in the South.

The way the Chinese community in this region pursued the acceptance of the white community can certainly come across as morally repugnant. And the fact that white society was so fixated on preventing interracial relationships can be taken as a sign that solidarity between Chinese and Black Americans had the potential to unhinge the logic of segregation. And even when Chinese Americans challenged the system, they did so with the aim of being recognized by it. We who have the benefit of hindsight can fault them for abetting segregation, but we also have to keep in mind the difficult circumstances they found themselves in.

Chinese Americans occupied a special place in the Jim Crow system in the region. It was both the cause of their economic success and the obstacle to bettering their lives. It could be said that they were a group that could only have existed in this unique time and place. Of course, the greatest irony about their story is that while they strictly observed Jim Crow, Jim Crow would never actually recognize them for who they were.

Looking for more AAPI-centered content? Check out our APAHM posts here!