'High Plains Drifter' Is Clint Eastwood's Mysterious, Overlooked Masterpiece

With the possible exception of John Wayne, no actor was more synonymous with the movie Western during the second half of the 20th Century than Clint Eastwood. The young actor had come to Hollywood from the San Francisco Bay area in the early ’50s, and thanks to his 6-foot-4-inch stature and good looks was signed to a $100-a-week contract at Universal, where he was quickly put to work in a string of hokey B-movies like Revenge of the Creature and Tarantula. Before he could despair over his flailing, fledgling career, he would be saved by the Western—a genre that immediately fit him like a bespoke duster.

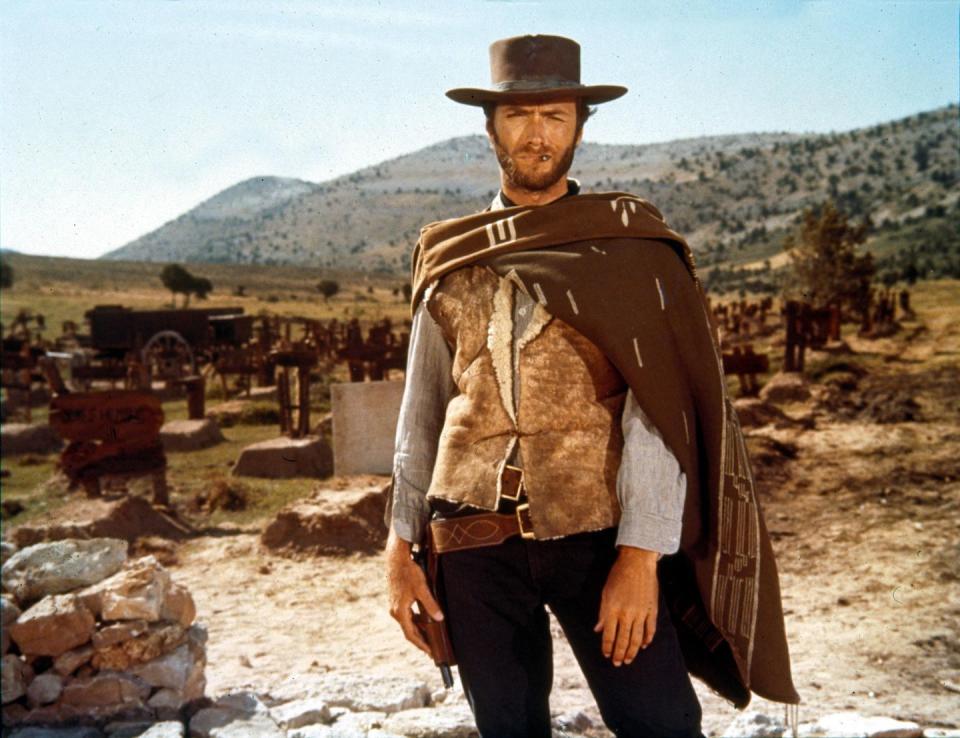

Although he’d already appeared in more than a dozen often-uncredited, blink-and-you’ll-miss-them parts by 1959, Eastwood’s career was salvaged when he was cast that year as Rowdy Yates on the hit TV oater, Rawhide. And it was during the show’s hiatus toward the end of its run that he was offered the lead role in Sergio Leone’s 1964 spaghetti Western, A Fistful of Dollars. Eastwood knew nothing about Leone—and frankly, there wasn’t much to know yet. But he took a what-the-hell gamble and flew to Spain to shoot the first installment in what would become Leone’s stylish, international sensation Man With No Name trilogy (which would also include 1965’s For a Few Dollars More and 1966’s The Good, The Bad and The Ugly). When the movies exploded like TNT overseas, no one was more surprised than Eastwood to learn that he had transformed into a global superstar overnight. Eastwood could finally say goodbye to the small screen once and for all.

As a freshly minted red-hot commodity both at home and abroad, Eastwood quickly parlayed his new-found bankability into a handful of macho and muscular studio pictures like the fish-out-of-water cop thriller Coogan’s Bluff and the bloated WWII action-adventure Where Eagles Dare. But like a Broadway-trained thespian who periodically returns to the stage to keep his or her instincts honed, Eastwood would keep circling back to the genre that had first forged his mythology in a crucible of six-shooters and squinting glances, the Western.

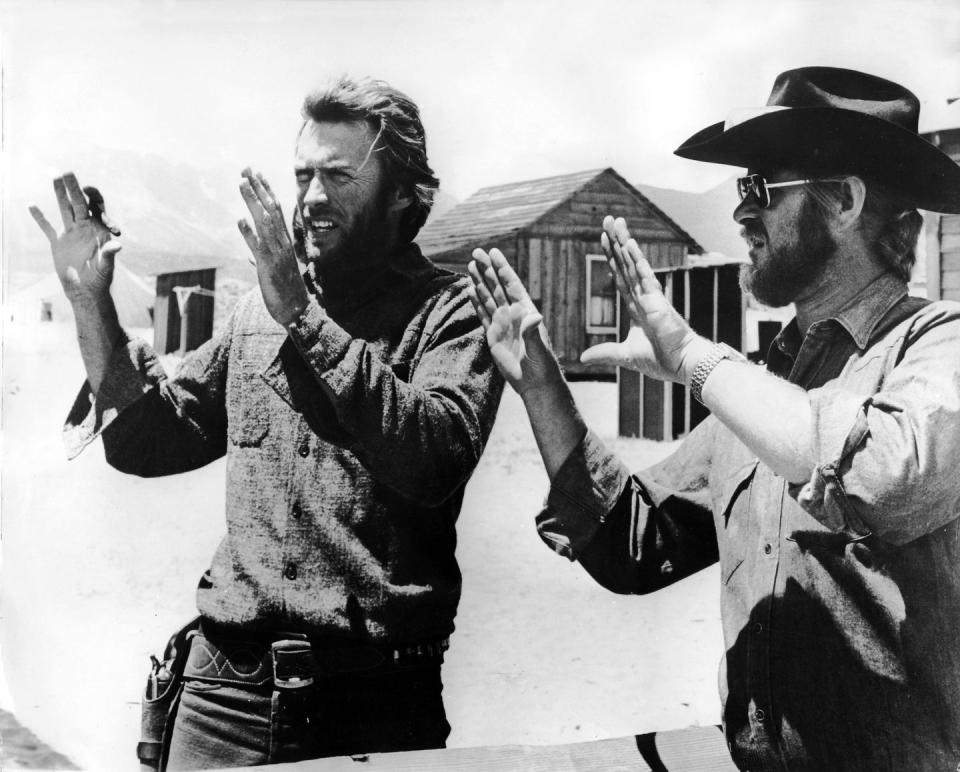

Eastwood proceeded to crank out a bunch of lean, economical Westerns—Hang ‘Em High, Two Mules for Sister Sara, The Beguiled—and was encouraged by his frequent director and most formidable mentor Don Siegel to try his hand behind the camera. And in 1971, he finally got his shot with the paranoia-drenched Fatal Attraction prototype Play Misty for Me. It was a hit. It turned out that Eastwood was a natural born director, albeit a different breed of one. In an era when New Hollywood movie-brat auteurs grasped for Art, Eastwood seemed to unconsciously position himself as their antithesis. He was mellow on the set, never asked for more than one or two takes, and made a habit of coming in both under-schedule and under-budget on his films—although he probably would have preferred to call them “movies” rather than “films”.

Which brings us to 1973’s High Plains Drifter, a movie that’s so frequently overlooked and uncharacteristically strange and surreal that it sticks out like a sore, red-painted thumb in the long sweep of Eastwood’s filmography. As stridently revisionist as any Western of the Vietnam era, High Plains Drifter is really only a Western on paper. I mean, there’s horses and saloons and tumbleweeds. But more than anything, it’s a ghost story (if you choose to see it that way…and I do) in frontier drag. It’s also a film that deserves to be seen by anyone who has a sweet tooth for the genre or thinks they have a bead on Eastwood as a filmmaker. It may also be the closest that he ever came to making an experimental, out-there movie.

High Plains Drifter was released in theaters on this day in 1973. And two decades before Eastwood would win Best Picture and Best Director Oscars for his return to the genre with the twilight apologia Unforgiven, he still hadn’t begun to grapple with the regrets and ramifications of shoot-first-ask-questions-later Old West violence. It wasn’t a hell of a thing killing a man yet. And High Plains Drifter is wall to wall with killing (not to mention some pretty un-P.C. rape and sadism). Not for nothing did it earn a controversial ‘X’ rating in the U.K. when it opened there.

Nowadays, we tend to think of Eastwood as a pretty conservative filmmaker. Not just politically, but also stylistically. He’s never been as thematically oblique or stylistically flashy (unless you consider his lack of flash to be flashy). He keeps things lean and simple. But High Plains Drifter is daring, weird and wonderful. Maybe that’s because back in 1973, working as a director for only the second time, Eastwood was still figuring out what kind of director he wanted to be. Did he want to be a stripped-down bareknuckle filmmaker like Siegel, or a baroque allegorist like Leone? For the first and last time in his career, High Plains Drifter would prove that he might just want to be both.

Written by Ernest Tidyman, who was a bit of an uncategorizable genre schizophrenic himself having already written both the Blaxploitation classic Shaft and earned a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for The French Connection, High Plains Drifter is a haunting and haunted supernatural revenge story about a mysterious, cigarillo-chewing man with no name (guess who?) who rides into the small mining town of Lago and immediately begins to toy with the locals, playing judge, jury, and executioner for their sins. You see, Lago is a town with a past. As we slowly learn in an onion-peel haze of almost-psychedelic flashbacks and dream sequences, the townsfolk silently watched as three of its scuzziest citizens brutally whipped Lago’s marshal, Jim Duncan, to death. Now, with those murderers just released from prison, they want Eastwood’s Stranger to defend them. But he has a score of his own to settle.

Tidyman said that his script for High Plains Drifter was inspired by the infamous 1964 Kitty Genovese case, where a 28-year-old Queens woman was stabbed and murdered as her terrified neighbors reportedly stared out their apartment windows and watched without calling for help. And Eastwood takes that Old Testament theme of payback for cowardice, hypocrisy, and inaction and grafts it onto the genre that he knew in his marrow. Over the course of the movie, Eastwood’s Stranger acts as if he’s Lago’s savior, but he’s not interested in protecting them, he wants them to pay for Duncan’s murder. Maybe…and this is where the movie gets really interesting…because he is Duncan. Or the ghost of Duncan, hanging in a tortured purgatorial limbo, until he can get a proper burial, a shred of justice, and some overdue payback.

The most eye-catching and best-known sequence in the film occurs when Eastwood tells the cowering citizens of Lago to paint every building in the town red as they await the three murderers’ return. Meanwhile, he picks up a brush to drip the letters H-E-L-L in crimson on a signpost at Lago’s border. These people want protection, but there’s no salvation for them. They’re already in hell for their sins (at least everyone other than Verna Bloom, who was the only person who tried to help Duncan). Still, it’s Eastwood’s flashbacks to Duncan’s murder-by-bullwhip that are even more horrifying—and technically dazzling thanks to Bruce Surtees’ fever-dream cinematography, Dee Barton’s eerie score, and Eastwood’s decision to have his longtime stunt double, Buddy Van Horn, play Duncan, making the physical similarities between Duncan and the Stranger all the more creepy.

I’ve watched High Plains Drifter probably a half dozen times and every time I’m more and more convinced that the Stranger is the ghost of Duncan meting out punishment from the Great Beyond. But Eastwood has always been cagier about interpreting his film, saying that that interpretation might be true, but it’s also possible that the Stranger is Duncan’s avenging brother. I hope he’s wrong, or just being playfully cryptic. Because it’s a far more interesting movie the further you get away from its Western-ness and the more it steps into the realm of spectral, mystical Tales from the Crypt pulp.

There’s one last reason why I adore High Plains Drifter and it really has nothing to do with what happens on screen. After the film came out and wound up being a big box-office hit, Eastwood wrote a fannish letter to John Wayne, suggesting that they make a movie together. It was one generation’s Great Western Star reaching his hand out to the previous generation’s. Wayne, who it turns out wasn’t a fan of the film, wrote an angry letter back, saying that High Plains Drifter “isn’t what the West was all about” and that it “isn’t the American people who settled this country.” The Duke may have thought that he was putting the young Eastwood in his place. And maybe it stung the young director at the time. But looking back now, I’d say that Eastwood comes out of that exchange looking like the victor.

You Might Also Like