Here's What to Expect When 'Speed Climbing' Makes Its Olympic Debut in 2021

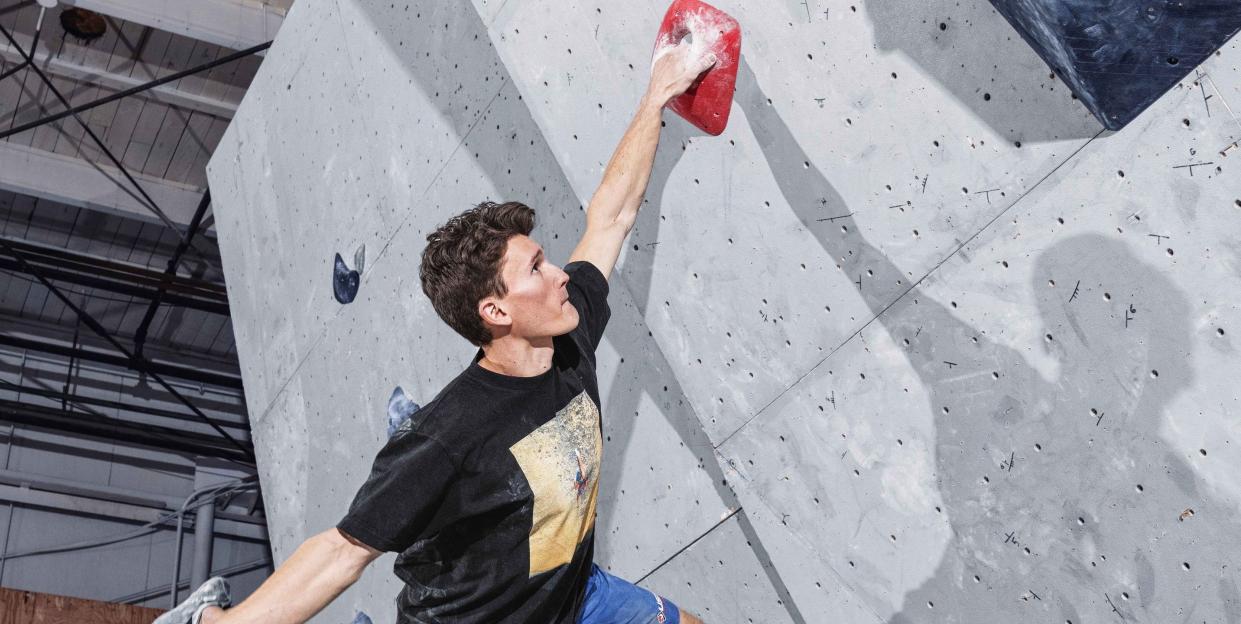

You may have been rock climbing before, but you’ve never done it the way Nathaniel Coleman is doing it right now at the Momentum Indoor Climbing gym in Salt Lake City. Coleman isn’t climbing so much as Spider-Manning his way up a 15-meter wall, all instinct and quick reflexes, just a few feet from the top in under six seconds. That’s where he coils his legs and leaps (yes, really), smacking the buzzer before falling backward to swing from his safety harness.

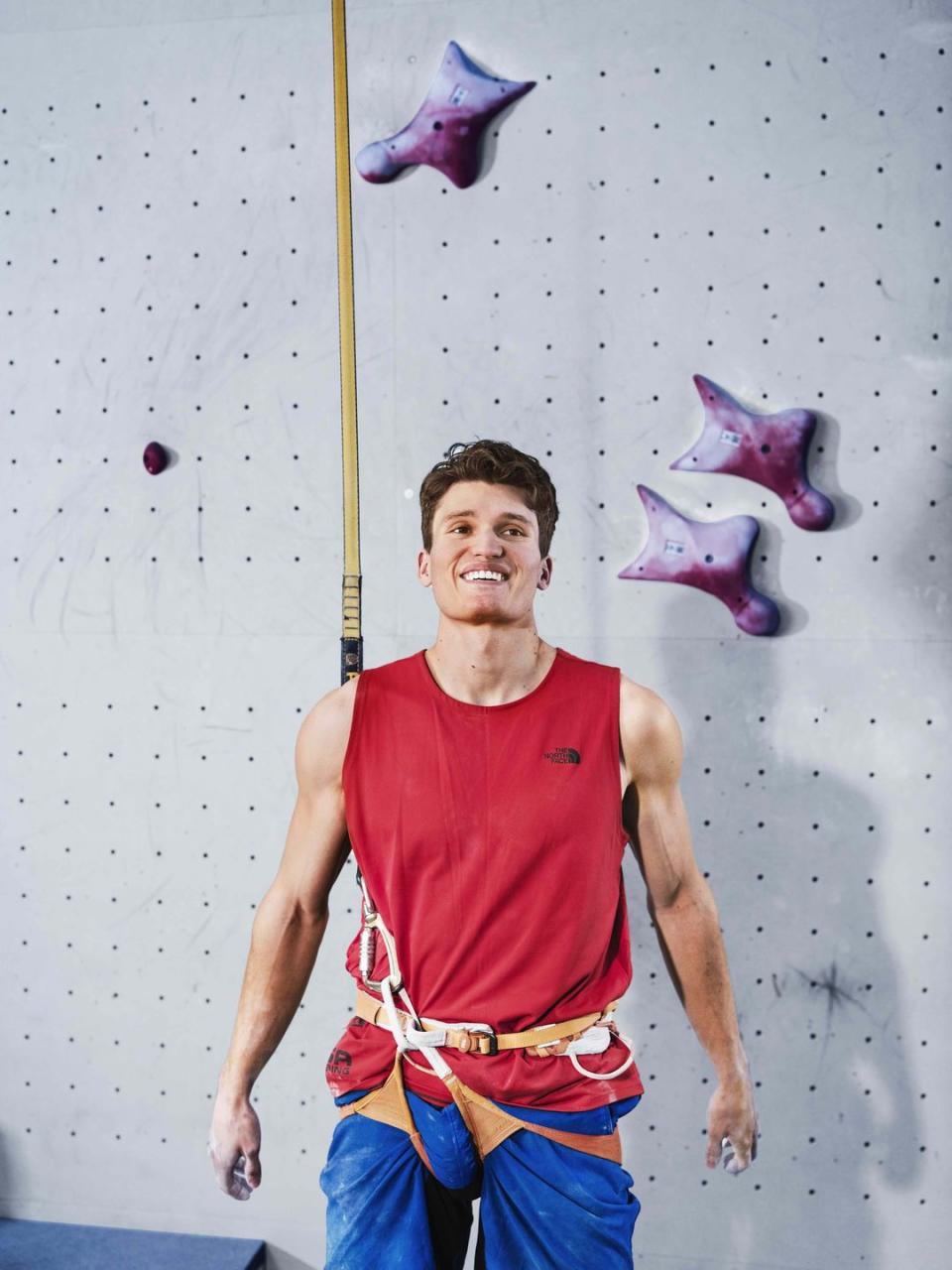

Electric, right? Except Coleman, one of the United States’ finest competitive climbers, can’t stand it. “Speed climbing is something I don’t like,” the 23-year-old says. “But sometimes you’ve got to do stuff that you don’t like.” Especially if that something can get you to Tokyo.

Top climbers worldwide are learning to embrace the same attitude. Competitive climbing was originally set to make its Olympic debut this summer in Tokyo, with a format that combined three different disciplines into a single event. (As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Olympic games are now scheduled to take place in July 2021.)

There are no medals for individual disciplines, though; athletes must compete in all three to have a shot at the combined climbing medal. Two of the disciplines are well-known. Lead climbing is what you’re most familiar with: You’re in a harness attached to a lead rope, attempting to scale a high wall filled with a challenging blend of holds. Then there’s bouldering, which involves climbing without ropes or a harness on a shorter wall, with blends of holds called “problems.”

The wild card for nearly everyone will be the third discipline, speed climbing, which is basically a vertical track meet. Two climbers line up in separate lanes, American Gladiator–style, then race 15 meters upward on a 5 percent inverted-grade wall, trying to reach the stop-clock at the top first. Some athletes love the playground-style face-off. “It’s the most natural thing you can think of: Who gets to the top of the wall the fastest?” says six-time U. S. national speed-climbing medalist John Brosler, 22.

Technically, all three disciplines have you racing the clock. In the first two, you’re trying to climb as high as you can (lead climbing) or solve as many “problems” in the fewest moves (bouldering) before time expires. But depending on whom you ask, speed climbing’s emphasis on, well, speed (over tactics) is either a spectator-friendly evolution of climbing—or a bastardization of the sport.

Blame Russia. In the 1940s, the Soviet Union prioritized speed in climbing competitions, and eventually the event joined the climbing World Cup circuit. In 2007, the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) established a standard for the speed-climbing course. The sport has grown in popularity since. It’s now contested in the U.S., too.

Around the globe, many competitive climbers, like Coleman, aren’t hyped to race up walls on autopilot. Lead climb-ing and bouldering are arguably more popular with climbers because the routes always change, and they more closely mimic the feel of an outdoor climb. But speed climbing also “lacks the critical problem-solving element that makes rock climbing so special,” says Coleman.

The best male speed climbers finish in less than seven seconds, and when the Olympic format was announced in 2016, Coleman’s performance in competition was nowhere near that. It wasn’t until he placed 31st in the speed portion of the combined format at the 2018 IFSC World Championships that he started focusing on speed. It takes “hundreds” of runs up the speed wall—memorizing footholds and handholds—before you get a feel for the wall, Coleman says.

While most climbing emphasizes grip strength, speed climbing pushes you to develop leg strength. Brosler, a vert-racing specialist who just missed the overall Olympic cut, likens the training to soccer drills, which focus on footwork and athleticism. He regularly does 100-meter sprints and barbell squats. “Your legs are where all the power comes from,” Brosler says. “At the elite level, your arms just kind of steer you on your way up, and your legs are like the motor providing all the power and momentum.”

In November, Coleman became the only U.S. male competitor to qualify for Tokyo, in part because he’d grown comfortable on the speed-climbing wall. Still tall and lean, he’s added the power and dexterity necessary to scale the course in 6.728 seconds, 1.25 seconds off the world record. “I realized—I think everybody realized," Coleman says, "that speed climbing is going to be a different beast."

You Might Also Like