‘It Felt Like Pure Love’: A Firsthand Look at Heroin’s Insidious Grip on Small Town U.S.A.

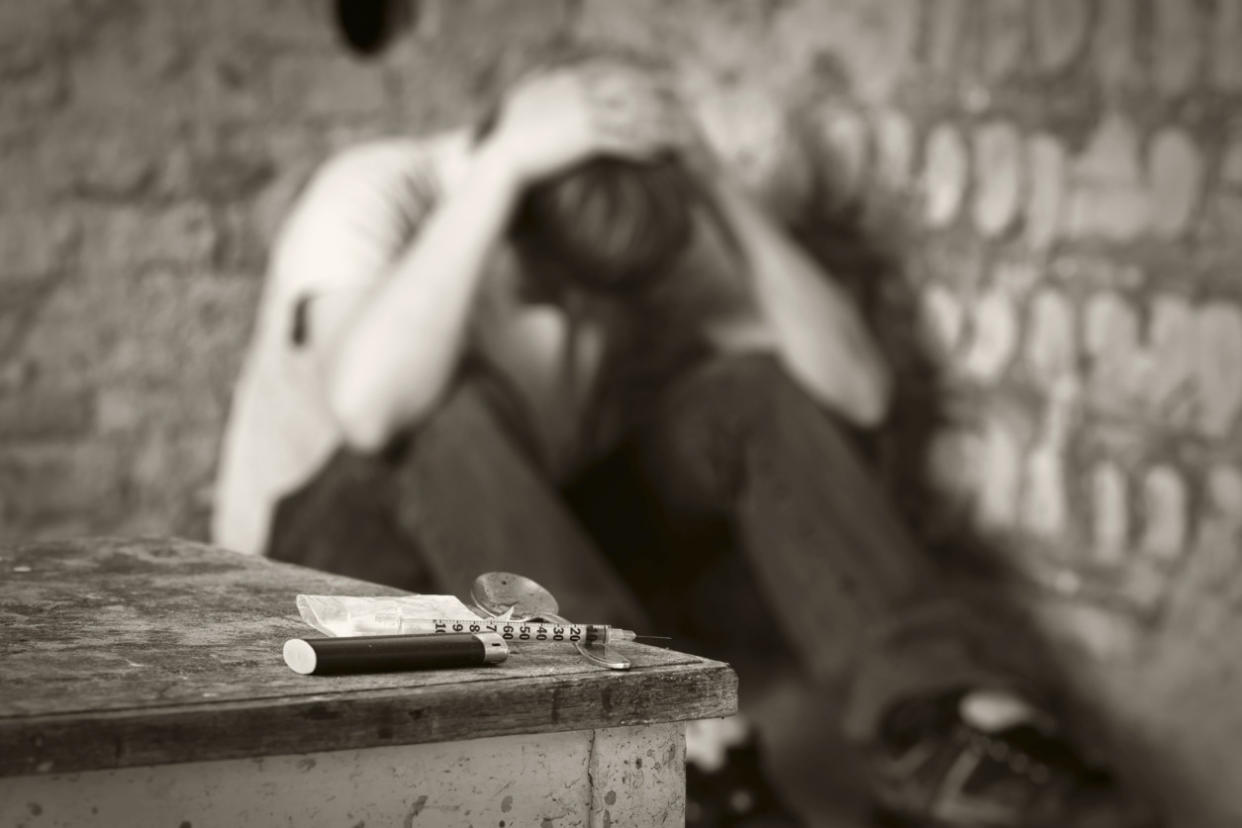

In the past, experts would hear prescription drug abusers say, “At least I’m not using heroin.” But not anymore. Once a drug mostly reserved for low-income inner-city men, heroin has now rapidly descended into suburbia and rural settings, supplementing — or replacing — pill abuse all together. (Photo: Getty Images)

He was in someone’s basement.

There was a dirt floor. A washer and dryer hummed nearby.

Those are the things Colby Henderson remembers about the first time he tried heroin. That and the feeling the drug gave him moments after the needle sank into his vein and the opioid rushed into his bloodstream.

“It felt like pure love,” Henderson, now 28 of New Hampshire, told Yahoo Health.

Having drunk alcohol and smoked pot since he was 13, Henderson had tried it all by the time he was 23. Except heroin. It was the one drug that always felt off limits, but that night, high on cocaine and pills and “who knows what else,” a friend of a friend, “some guy, really,” shot him up.

The chaos in Henderson’s life rolled out like a red carpet after that: Overdoses in cheap motels, stealing from friends and family, seizures, ER visits, homelessness, rehab and relapses, chasing the high, detoxing from the high, spending the next several years trying to get that feeling of pure love back.

He never could. He never would.

Colby Henderson. (Photo: Courtesy of Colby Henderson)

“My life became heroin. I’d be running back and forth trying to get heroin, trying to get away from heroin, detoxing from heroin, going back to heroin,” said Henderson. “It becomes maintenance. You stop getting that rush and then you just don’t want to get dope sick. It feels like there’s no way out.”

The use of heroin, one of the most addictive drugs in the world, rose by 63 percent between 2002 and 2013 in the U.S., according to the CDC.

In that same time frame, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled. More than 8,200 Americans died in 2013 from the drug.

With tighter regulations on opioids and crackdowns on “pill mills,” along with lower street prices of heroin, the drug is reaching demographics that it typically hadn’t in the past – women, those who hold private insurance, and the high-income sector.

And now new research from the Washington University at St. Louis School of Medicine is explaining those demographics even further. Most heroin users aren’t abandoning pills all together. The study, which surveyed 15,000 patients at drug-treatment centers in 49 states, showed that heroin, much cheaper and more widely available, is sometimes seen as a last resort when money is too tight or pills aren’t as readily available.

Lead author of the study Theodore J. Cicero, who has been studying heroin use since the 1970s, said in the past he’d often hear prescription drug abusers say, “At least I’m not using heroin.”

But not anymore.

Once a drug mostly reserved for low-income inner-city men, heroin has now rapidly descended into suburbia and rural settings.

The spike in usage shows a “shadow effect,” Cicero told Yahoo Health. Those who stuck to pills in the past, typically people who had more disposable income, are reporting a more difficult time getting their hands on pills and have turned to heroin to get a similar, albeit more potent and dangerous, high.

“Doctors, lawyers, students, I see it all in here,” said Dr. Kenneth Brown, a staff physician at Hampstead Hospital in Hampstead, NH, which specializes in treatment for chemical dependency. “This drug doesn’t discriminate.”

Costs of street drugs vary throughout the country. A single dose of a prescription painkiller runs around $30 in New Hampshire. A single dose of heroin can go for as little as $6.

The study, which was published in New England Journal of Medicine, also revealed the regional variations of the opiate use.

“On the East and West coasts, combined heroin and prescription drug use has surpassed the exclusive use of prescription opioids,” said Cicero.

With a backdrop of an idyllic Norman Rockwell-like scene, northern New England is one of hardest hit areas of heroin addiction.

New Hampshire, in particular, has some of the highest per capita rates of heroin in the country.

Lt. Kevin Duffy of the New Hampshire State Police said his unit now deals with heroin in some capacity nearly every day. The state saw 328 heroin-related deaths in 2014, up exponentially from 36 in 2011. “We’re on track to supersede last year’s number,” Duffy said.

Because of the explosive rate of addictions and deaths, law enforcement, rehabilitation centers and policymakers are looking to “start thinking out of the box,” with a unified approach to tackle the epidemic.

“It can’t be an us-versus-them thing anymore,” said Duffy. “That’s not going to stop this situation.”

Colby Henderson. (Photo: Courtesy of Colby Henderson)

Henderson had always liked to party. He was able to “skate by” in high school without too many consequences, despite drinking and smoking weed regularly. After being introduced to cocaine his first week of college, Henderson “fell in love with it immediately.”

He was suspended after his first college semester for poor grades. “Even then, I didn’t know I was an addict. I didn’t think drugs and alcohol were the problem. I thought they were the solution to take my problems, my fears, away.”

Only later did Henderson realize he was riddled with depression and anxiety, and he used the drugs and alcohol to alleviate the uncomfortable feelings.

“Most people who are using these drugs have low self-esteem, and we need to be able to treat the person before they find themselves in a horrible, life-changing situation when someone can truly lose everything,” said Cicero.

“A lot of addictions start as self-medicating,” said Brown, who treats heroin addicts every day at Hampstead Hospital.

Detox, in which patients experience painful muscle cramps, chills, hot flashes, nausea, vomiting, temperature instability, typically lasts about six days. That’s only the beginning of treatment, though. Brown says it’s important for those in recovery to seek out therapy to manage depression, anxiety and potential suicidal thoughts that can come from new sobriety.

Related: Heroin Use in US Reaches Epidemic Numbers

“Often times, coping skills are as mature as the age at which people pick up their first drug,” said Brown. “So there’s a lot of catch up work to learn new coping skills that don’t include drugs or alcohol. And that can be tough.”

Like many other states, Duffy said New Hampshire is looking to educate the public on heroin addiction. Kids should be learning about the debilitating effects of heroin as young as grammar school, Duffy said.

“Desperate times call for desperate measures, and the best way we can really stop this epidemic is to get to young people before they even think about picking up the drug,” he said.

Cicero agreed: “People say that it’s too big of a task to take on, but look at the tobacco campaigns. We’ve seen great success there. It’s a huge undertaking, but it’s possible. And we need to do it.”

Once a person is in the vortex of addiction, “delusion is strong,” Henderson said. It’s important to get to people before they’re in the midst of the chaos.

It was several years after that first heroin hit in the dirt-floored basement when Henderson had a moment of clarity.

Having been up all night doing drugs, mixing Xanax and heroin, “a super dangerous combination,” he was strung out. Homeless with no money, Henderson needed to fend off the dope sickness before it hit him at any moment.

“I had one of those pre-paid credit cards with no money on it. My plan was to go to a bar and open a tab with it, drink as much as I could and then leave the bar without signing the bill.

“I felt totally worthless,” he said. And in that moment as he parked the car in front of the bar, his mother drove up beside him.

Colby Henderson. (Photo: Courtesy of Colby Henderson)

“It was one of those crazy life moments. I didn’t know why or how she was there. But we looked at each other and she knew I was shattered.”

Overwhelmed and ashamed, Henderson drove away.

“I was so damn sick of myself, so disgusted with myself,” he said. A few hours later, he called his mother. She and his father helped get him into a rehab facility that day. It’s now been 15 months since Henderson has been off heroin.

Related: CVS Makes Big Move in Fight Against Heroin Deaths

“I can’t imagine what it was like for them to essentially have to watch me kill myself, to build up their hope and tear it down over and over again,” he said.

Henderson said he was lucky to have family to call. Not every addict has anyone left to answer the phone.

“I was given a gift,” said Henderson, who still says he has to take his sobriety day to day. “Now it’s all about consistency and staying focused.”

With his ability to empathize with other addicts while also being living proof that people can get clean, Henderson hopes to help others who are living similar lives that he once did. “A lot of my friends weren’t given that gift. A lot of my friends are dead.

“Heroin addicts need to know they’re good enough,” he continued. “That they’re good enough to be here, apart of society, that they deserve a good life.”

Let’s keep in touch! Follow Yahoo Health on Facebook,Twitter,Instagram, and Pinterest. Have a personal health story to share? We want to hear it. Tell us at YHTrueStories@yahoo.com.