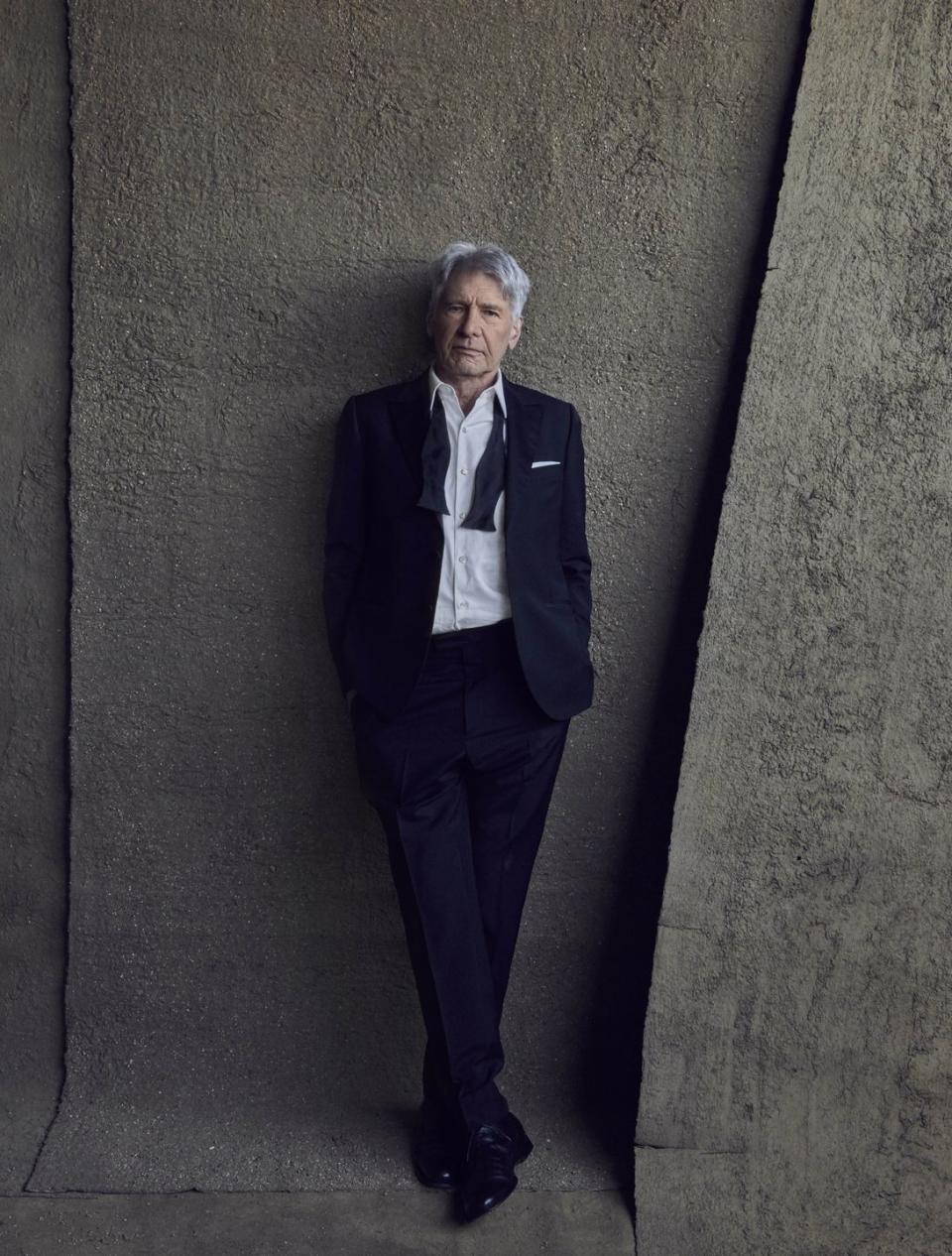

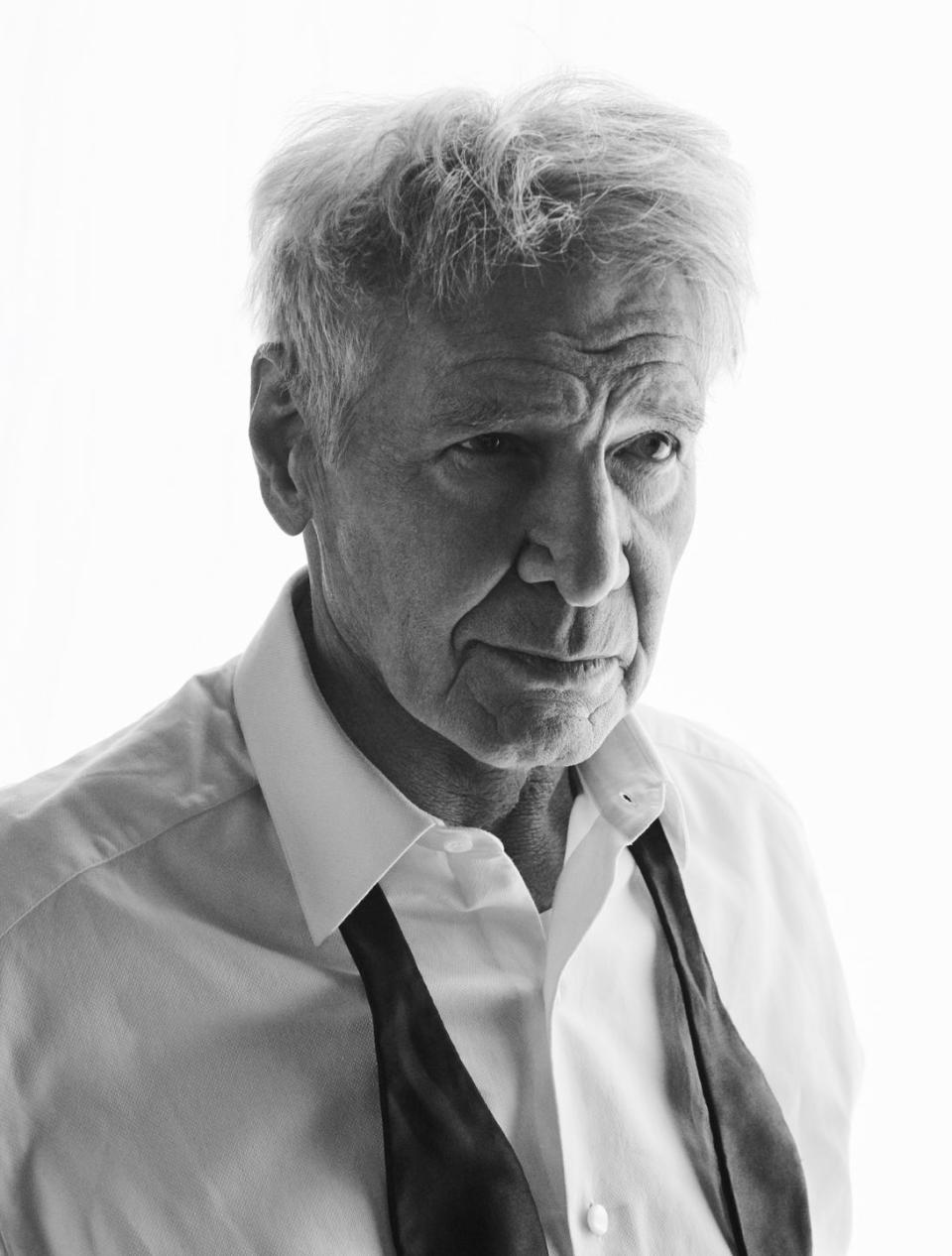

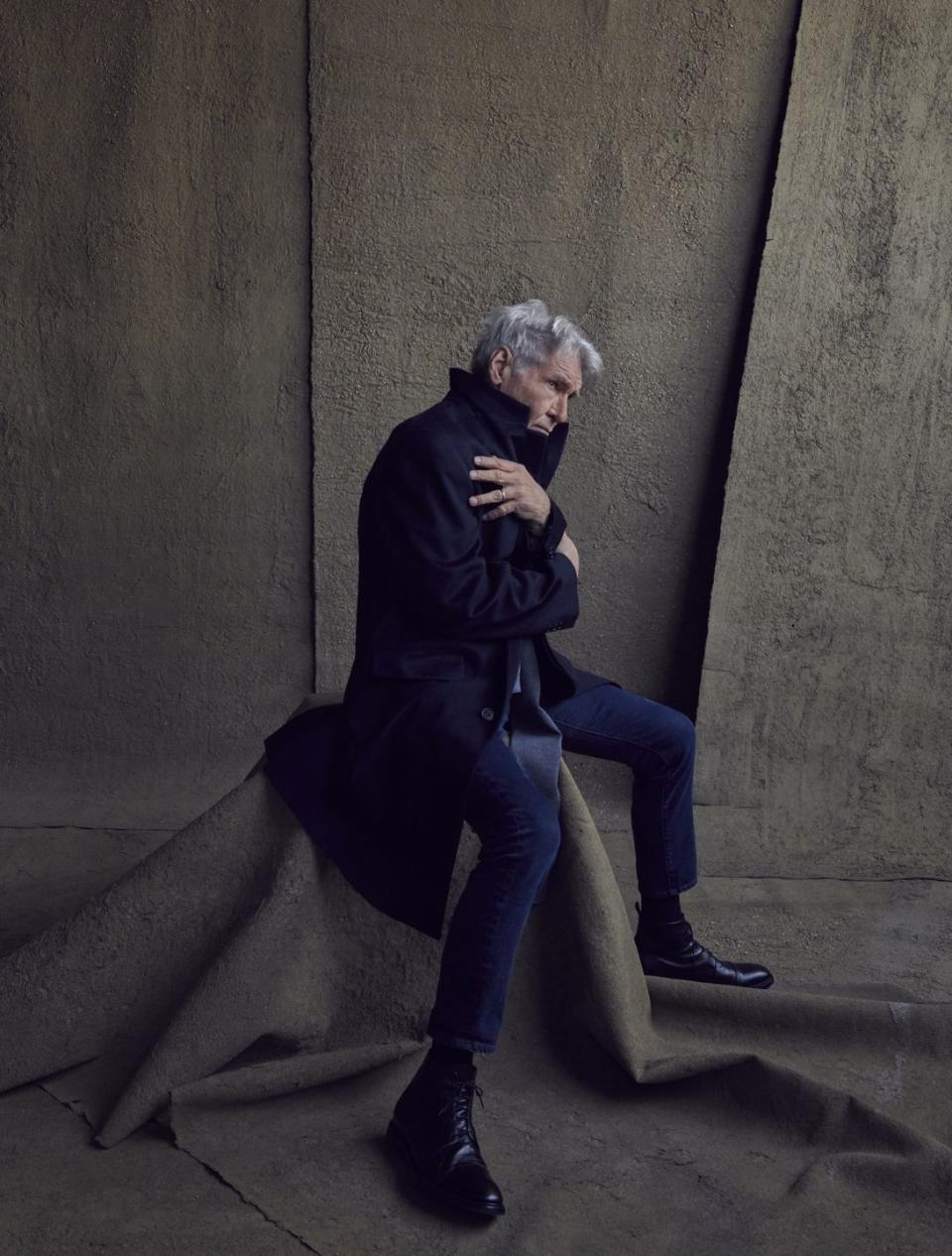

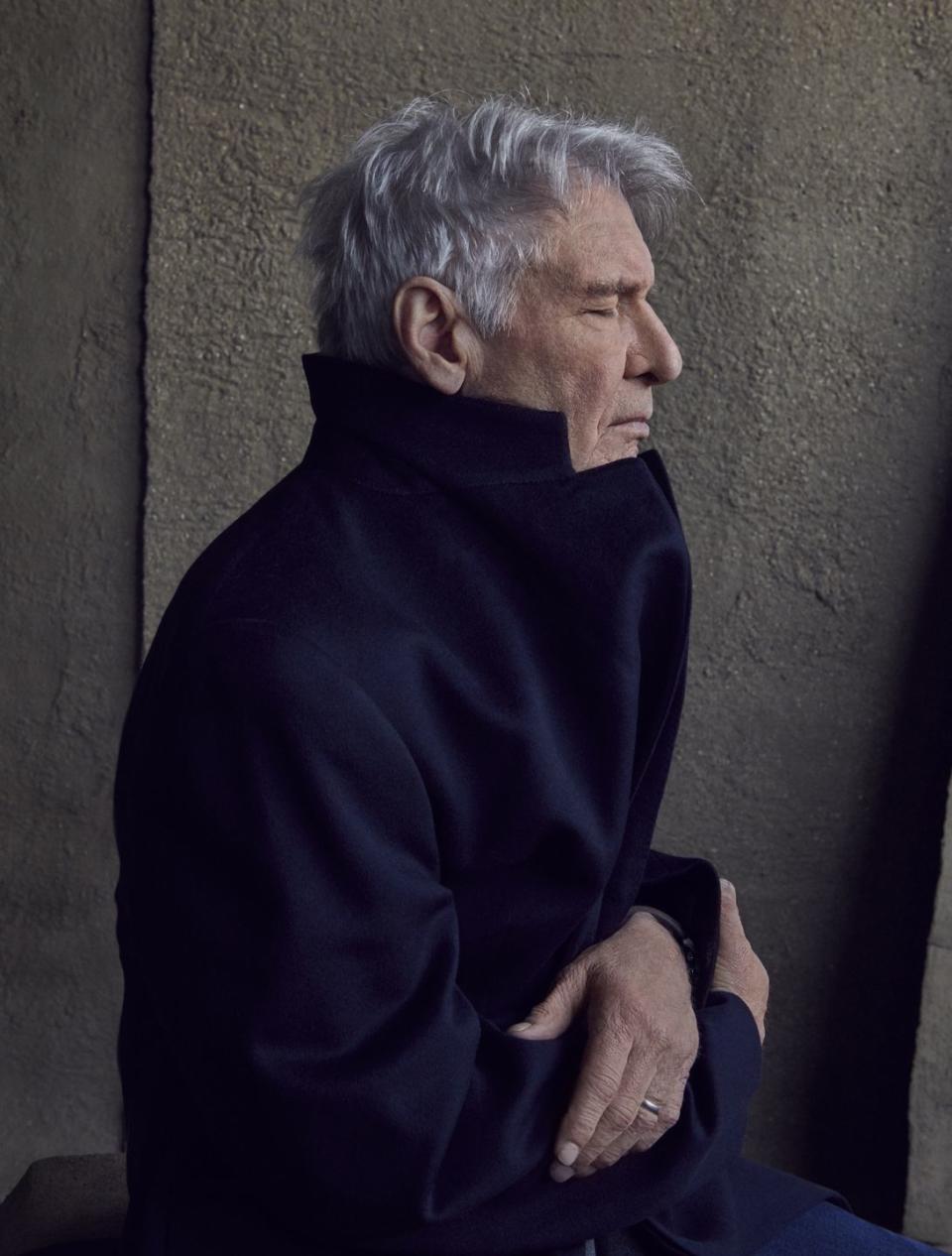

Harrison Ford Has Stories to Tell

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

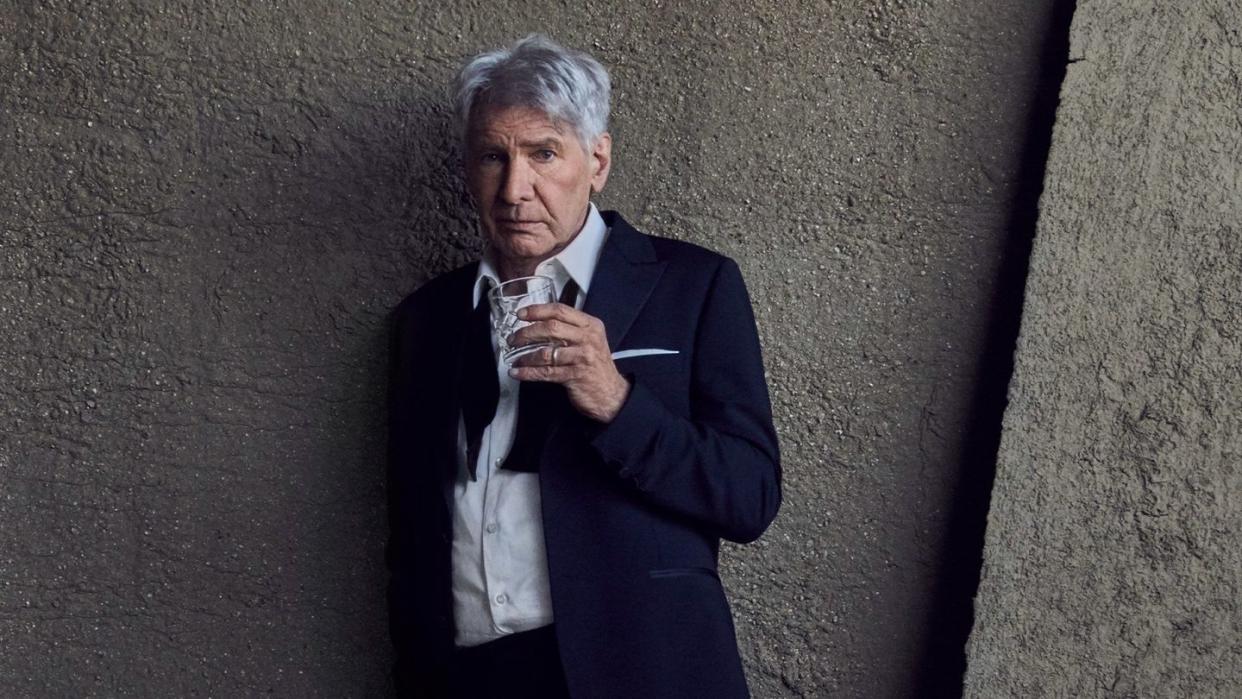

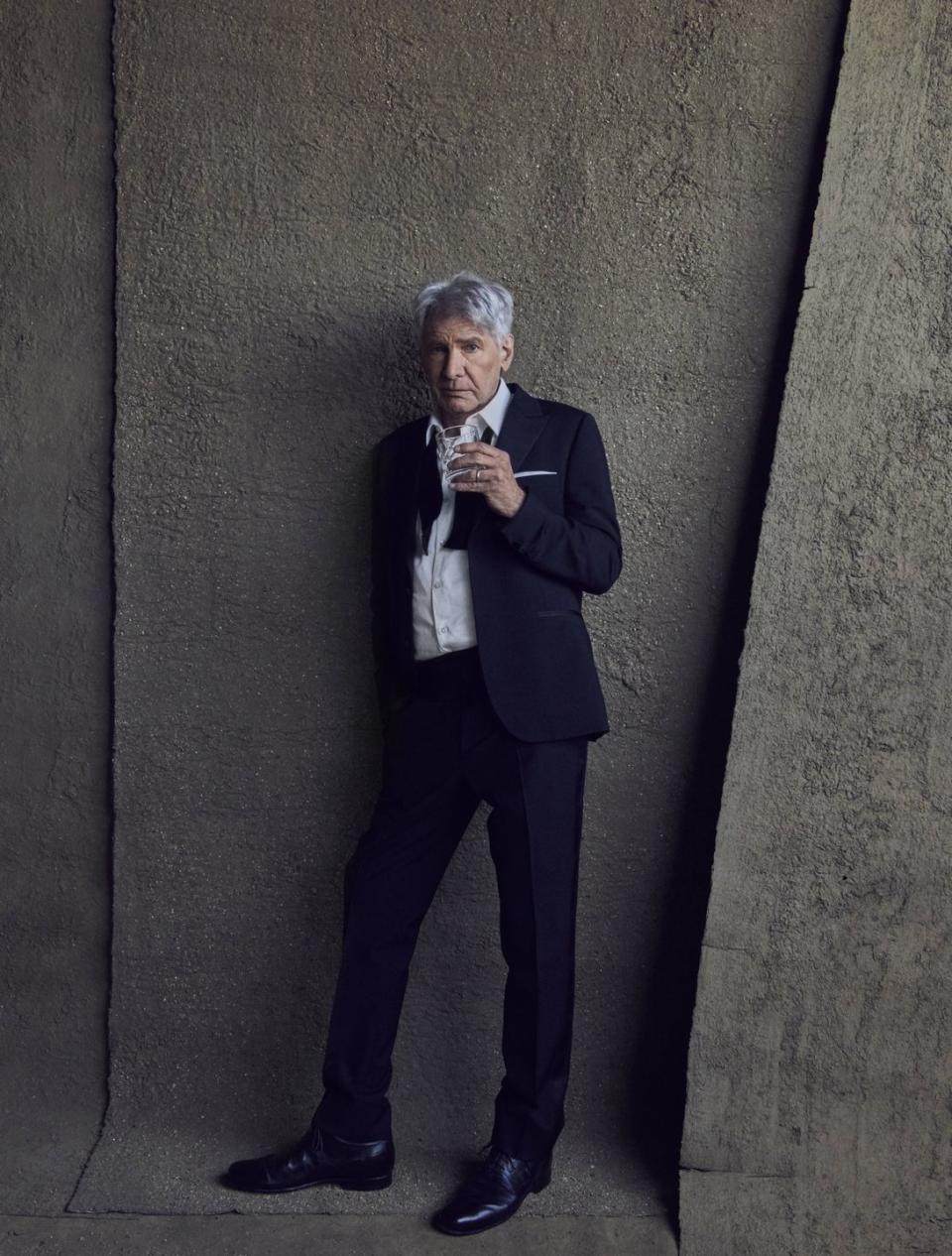

The last time I spoke with him was on the phone, three weeks after we drank bourbon at his house. We sat at the bar in what I’ll call the family room, a gleaming wooden bar with the bottles lined up behind, organized in neat rows by type of liquor. We ate Emmentaler cheese that Harrison Ford had sliced in the kitchen with a silver cheese knife and arranged on a plate with a handful of wheat crackers. That was in Los Angeles, where he lives when he’s not at his most-of-the-time home, the ranch in Wyoming that he bought in the eighties.

He was now in Atlanta. His voice, the unmistakable rich, low grumble, came through the phone obscured by some shuffling in the background.

“How you doing?” he asked.

In movies, Ford’s voice can tremble and quiver at low volume, just enough to communicate a terrifying degree of urgency, like if you don’t do what he says right now, people could die.It can jump to a sharp holler when things get even worse. His voice can be tender. It can be funny and biting.

On the phone, he just sounded like a guy on a Sunday afternoon. The background shuffling quieted.

“I’m learning a bunch of lines for tomorrow,” he said, exhaling.

He was in Atlanta filming Captain America: New World Order, the fourth film in that franchise, in which he will play the president of the United States for the second time in his career.

I apologized for needing this additional time on the phone after he had been so generous in Los Angeles—breakfast, airplane hangar, driving around in his Tesla, the drinks at his home—but he said, “Don’t be silly.”

This would be our final interaction before I had to write this story. So, under pressure, I had to ask all lingering questions while approximating the kind of breezy conversation that tends to yield good article fodder. (He knew all of this, because we had talked about what exactly I was trying to accomplish, and what exactly he was trying to accomplish, with this article.)

“Is it fun, making a Marvel movie?” I asked, this being his first.

“Uh,” he said. “Yeah. I mean, there are tough days and easy days and fun days and all kinds of days. It’s a tough schedule and, yeah, it’s fun. But it’s not a walk in the park. It’s not fun fun. It’s work.”

This was work, too—taking my call on a Sunday afternoon—which I knew because we had also talked about that. Almost every profile I had read of Harrison Ford had been pretty much a story about what it’s like to write a profile of Harrison Ford, and how he’s grouchy, difficult, impatient, or unwilling to talk about himself, and whether the writer can get him to talk about himself—can get him to finally, in this story, reveal the real Harrison Ford. He let me know early on that he doesn’t think that’s the point of these stories at all—the interviewer asking cleverly worded questions designed to lull the actor into revealing his demons and secrets and things he’s never told anyone, and the actor just trying to promote a movie.

As we talk on the phone on a Sunday afternoon, I think about the first morning we met, for breakfast. I told him that, with every assignment, I always try to write the greatest magazine profile ever written. (Silly, and true.)

And he said, “Well, that’s fine, but you’ve got to have material to work with.” He stopped cutting his chicken sausage for a second and pointed his knife and fork right at me, his eyebrows up.

“I’ve got to participate.”

He called my cell as I was pulling out of LAX in my rental car. Our first interaction.

“Hi, it’s Harrison Ford,” he said.

He was wanting to know what I might wish to do the next morning, when we would meet. This was unusual—the celebrity-profile subject calling to make the arrangements. He said he had some errands to do but that we could meet after. I said that might actually be kind of funny and interesting: Harrison Ford doing errands.

“Well, what I mean is I’m getting my hair cut,” he said. “The guy is coming here to the house to cut my hair for this Marvel movie. You want to come and see me get my hair cut?”

“Yeah, that would be great!” As I said it, too excitedly, I realized how weird it sounded. “I just mean...”

“Okay,” he said, giving me the address and the instructions for the gate. “See you tomorrow.”

About four hours later, he called me back. The haircut guy wasn’t coming after all, so why don’t we just meet for breakfast at nine?

“Sorry about all this,” he said.

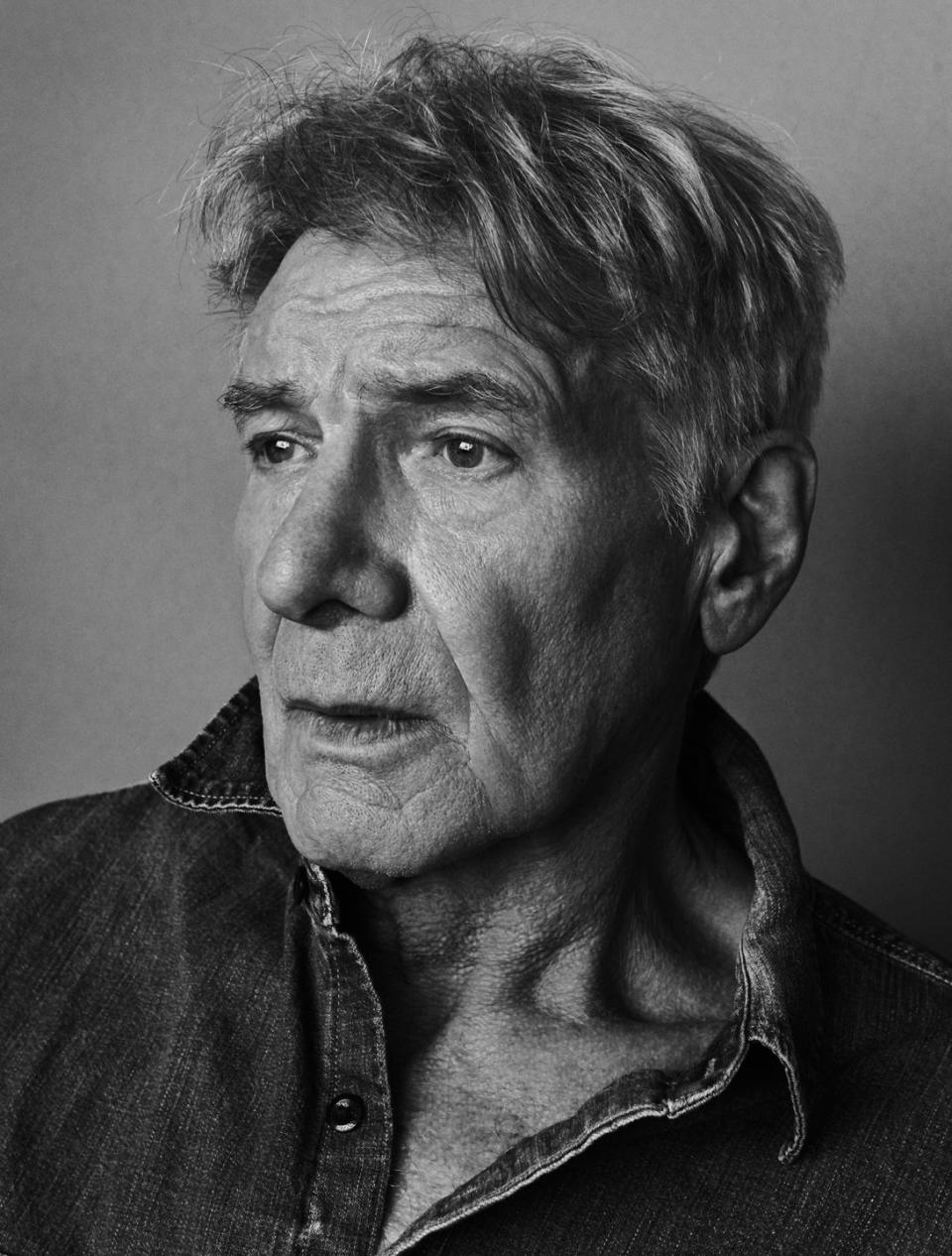

He arrives at the fancy, market-driven place in Brentwood one minute early and quickly gets to the business of finding a good table. There’s a skylight, and a square of sunlight frames him as he stands in the middle of the restaurant, pointing this way and that with the hostess, smiling a thanks when they settle on a two-top near the kitchen.

He tells me he just ran into Bob Iger, the CEO of Disney, the company that will release Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny on June 30. It’s that kind of joint. Barely beyond pleasantries, Ford is now talking about airplanes. He’s been flying for twenty-eight years. “I will not be buried under a stone that says actor,” he says. “For me, flying is as important a part of my life as my business. It’s not like playing golf.” He gets to talking about an organization called Young Eagles, which holds events at local airports on Saturday afternoons where pilots take kids for half-hour flights to pique their interest. Ford was president of the group for five years and took up dozens of kids himself.

This article appeared in the Summer 2023 issue of Esquire

subscribe

“Here’s the thing,” he says. “When we take a kid up, we’re actually investing his voting mother and father in general aviation, which is different from commercial aviation. People don’t understand both the value and the contribution to the economy, and the community, that general aviation provides. General aviation—that’s the farmer who’s flying his produce to a farmers market, that’s the mechanic with his tools who’s flying out to fix another airplane, that’s a doctor in Montana who’s flying himself from clinic to clinic. It’s me when I go to fuckin’ Haiti to drop off supplies and doctors when there’s an earthquake. It’s a whole community of people who contribute to the economy who are getting squeezed out because the government would rather concentrate on commercial aviation. And we have been beset by losing airports for the economic opportunity that they present in another form.”

He starts grabbing silverware and arranging it on the table.

“So look. Here’s Santa Monica Airport. Here’s the runway. [Bangs fork down.] Here’s the beach. [Knife, perpendicular, a few inches away.] And between the airport and the beach? [Slaps napkin down, indicating the city.] The height of buildings is limited by the FAA because of plane traffic taking off. So they took fifteen hundred feet off a five-thousand-foot runway to squeeze people out—airplanes—so they could build higher buildings over here. [Bangs the napkin.] Of course then they do a survey among Santa Monica voters. ‘What are the ten things that most need to be done?’ Number ten on their list is to get rid of the airport. But number one on their list is traffic congestion. [Lowers chin, raises eyebrows, points at me.] I rest my case.”

“So that’s why Young Eagles is about the parents, too,” I say.

“Fuckin’ A,” he says a little too loud, drumming his fingers on the table, which he does sometimes when he gets going on a topic. He smiles: “Hey, if you don’t mind, leave the ‘fuckin’ A’ out. My wife is still giving me shit about that Hollywood Reporter thing, and I’m trying not to say that too much.” Earlier this year, that magazine printed an interview with him, which he will bring up several times during our conversations. “Me and the writer were sitting on folding chairs in a horse stall. It didn’t feel like a formal enough atmosphere to have to clean up my language,” he says. “And they printed every single fuck.”

In a career full of moments, Ford is having yet another. That Reporter interview was to promote Shrinking, the Apple TV+ comedy on which he costars as a psychiatrist. It could just as well have been for 1923, the Paramount Plus western that is a part of Taylor Sheridan’s Yellowstone TV colossus.

I tell him I rewatched the previous four Indiana Jones movies with my son last week.

He points a bony, roughened finger at me. “Advantage: you,” he says.

“Do you watch your movies?”

“Fuck yeah—until I can’t do anything about it.”

“So you watch it only while it’s getting made.”

“Yeah. When it’s done, it’s done. I’m making something else. Fucker’s on his own.” He grimaces at his persistent profanity.

“This is why I get in trouble,” he says.

“Okay, but can I put that one in?”

He shrugs and then nods, seeing the narrative value of that particular fuck.

“Yeah, that one works.”

He laughs. (Ford is very funny, in movies and in conversation. Karen Allen, his costar in Raiders of the Lost Ark, calls it “that wonderful, dry humor that comes at you sideways.”) The waiter comes to take our order. You get to pick how you want your eggs with the Farmer’s Breakfast, and Ford says, “Poached, please—and runny.” And here he turns his gaze from the menu up to the waiter, looks deep into his eyes with a sudden ferocity, curls his lips around his teeth, and says, “And when I say runny, I mean run-nee!” as if he’s in The Fugitive saying, “I didn’t kill my wife!”

The waiter does a small bow, manages a smile, and whispers, “Okay.”

Most people know a good deal about Harrison Ford. His path to becoming an actor was methodical and uneventful: going out for parts, landing small roles. He figured he could be a character actor. “Anyone but the leading man” is how he describes it. A working actor. Getting paid and going home at night.

Then there’s the famous thing that happened, a story of which there are many versions, but this is the right one: Ford had got a small part in the second feature film by a young director named George Lucas, 1973’s American Graffiti. But he had a young family and wasn’t making enough to live on, so he worked as a carpenter. A friend who had designed the millwork for the entrance to Francis Ford Coppola’s offices couldn’t find a carpenter to install it. “He appealed to me,” Ford says. “I said I would do it but only at night, when no one was around, because I didn’t want to be that guy—I wanted them to think of me as an actor, which I was. I did the job. While I’m finishing up, first thing in the morning in walked George Lucas and Richard Dreyfuss to begin the process of meeting people for Star Wars. George had told our agents he wanted new faces, not the same people from American Graffiti. I was there with my tool belt on, sweeping up, said hello, chatted, and that was it.

“Later, I was asked by the producer to help them read lines with candidates for all the parts. Don’t know whether I read with people who were reading for Han Solo—can’t remember. I read with quite a few princesses. But there was no indication or forewarning that I might be considered for this part. It was just a favor. And then of course they offered me the part.”

Han Solo was Ford’s first role of significance—and yet even then, according to his similarly amateur costar Mark Hamill, Ford already had a world-weary way about him. “I was wide-eyed and inexperienced, and Harrison arrives, and I’m telling you—from day one—just like Luke did, I looked up to him as someone who had a firmer grasp of all the elements than I did,” Hamill says. “I thought, This guy’s like... Steve McQueen? Gary Cooper? John Wayne? He was instantly iconic, and yet the world at large didn’t know who he was. I just thought, This guy’s major.”

Star Wars led to all kinds of things, including Indiana Jones, a character Lucas developed for a movie that would be directed by his friend Steven Spielberg, 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. (This is skipping a lot, but that’s the general timeline.)

For a few overlapping years in the 1980s, Ford’s likeness was on not one but two lunch boxes, one of the surest measures of superstardom in that decade. Non-lunch-box landmarks included Blade Runner (1982), Witness (1985), The Mosquito Coast (1986), and Working Girl (1988). The nineties brought Presumed Innocent (1990), Patriot Games (1992), The Fugitive (1993), Clear and Present Danger (1994), and Air Force One (1997). You know all of this.

What you don’t know is what happens when they mess up Harrison Ford’s eggs. The plates come, two Farmer’s Breakfasts. Mine’s good: over easy. As Ford cuts into his first poached egg, I’m asking, “So would you say the character of Indiana Jones has some of your own boyhood—”

He lays down his fork and knife. His shoulders droop in defeat.

The egg white is rubbery, the yolk chalky. He looks up at me.

“You couldn’t have been clearer,” I say.

The waiter, seeing a problem, scurries over, eager and recoiling at the same time. Ford just looks up at the poor guy, not with anger but with something worse: disappointment. It’s not a mean look. It’s a look that says, “We can do better, friend.”

The waiter is smiling and trying to speak, and he looks as if he might cry. “Are they... not soft?” He slinks away. Ford tries to refocus.

A waitress returns with two beautiful jiggling poached eggs on a plate.

“Sorry to be so awkward,” he says, smiling at her. “Thanks.”

And now that he has two runny poached eggs, he clicks back on and looks up at me like “Okay, what now?”

“I guess the point is, these stories we see—movies, novels—we look for ourselves in these characters and these stories,” I say, rebooting.

He nods. “We look for ourselves, and we look for useful information to help us navigate our fucking lives and the world that we’re living in,” he says. “We don’t realize we’re looking for that. But we’re looking to pull out of a fantasy something that’s useful to us. And what’s useful to us is to emotionally participate in things outside of our own lives.”

Why make another Indiana Jones movie, filmed when he was pushing eighty? “I wanted an ambitious movie to be the last one,” he says. “And I don’t mean that we didn’t make ambitious movies before—they were ambitious in many different ways. But not necessarily as ambitious with the character as I wanted the last one to be.”

Early in The Dial of Destiny, there’s a scene in which Jones is riding a horse on a subway platform in Manhattan. As Ford finished the scene, he felt hands all over his legs and, he says, “I thought, What the fuck? Like I was being attacked by gropers. I look down and there’s three stunt guys there making sure I didn’t fall off the stirrup. They said, Oh, we were just afraid because we thought, you know, and bah bah bah bah. And I said, Leave me the fuck alone, I’m an old man—”

He’s raising his voice now.

“Sorry.” He lowers his voice, but his fingers are drumming like mad. “Leave me alone, I’m an old man getting off a horse and”—loud voice again, he can’t help it—“I want it to look like that!”

There’s another moment in The Dial of Destiny: Indiana Jones is in hand-to-hand combat with the villain on a speeding train, and he holds his famous hat over the villain’s face before punching him, as if to take him by surprise. It’s a brilliant bit of Jonesian theatrics, and it was Ford’s idea—the kind of thing only he would think of, having inhabited Jones for so long.

Over a fifty-year career and an eight-decade life, Ford had banged himself up from time to time—snowboards, horses, stunts. Something must have weakened his shoulder, because when he held his hat in the face of actor Mads Mikkelsen and pulled his hand back to demonstrate the punch—someone was in the way and he had to adjust mid-strike—Ford pulled the subscapularis muscle off his right shoulder. Production shut down for two weeks, and Ford had to sit out an extra six weeks after that.

“Well,” I offer, “you’ve always been known for doing so many of your own action scenes.”

“Yeah, well, I’m also known for shutting movies down because I get hurt, which is not something you want to be known for. But hey, shit happens.”

He inhales, exhales, drums the table, and raises his eyebrows: Okay, next?

We are sitting in his airplane hangar. That is a sentence his wife, Calista Flockhart, would rather not see in this story, he tells me, because it just makes him look like a rich guy with planes. Which he is. He left Santa Monica because he was pissed about the shortened runway, and he built a hangar of his own at another airport. There’s a nice living room and office, with a kitchen and wood paneling and sofas.

Yes, in the twenty-eight years he’s been flying, there was a crash—the result of mechanical failure. The week before we met, he had completed his annual recurrent training, required of all pilots with a certain rating.

“Flying is the tension between freedom and responsibility,” he says, “the obligation on every flight to ensure the safety of the people aboard. It’s serious. And I continually have to meet the standards.” He pauses, then smiles and holds a finger up. “And: It’s the third dimension! We’re living the two—dimensional life here on the ground. [Loud table drumming.] When you get up there and you see the third dimension—that’s what’s so exciting about these kids, the Young Eagles. You fly ’em over their house and it’s the first time they really know where they live.”

It’s interesting to hear Ford talk about kids, because while he has five children of his own, in movies he has rarely taken on the role of a family man. Even if one of his characters has kids, they’re not usually integral to the story. The Fugitive, Blade Runner, Witness, Working Girl, the Tom Clancy movies, Air Force One, The Devil’s Own—not a lot of parenting going on. The Mosquito Coast—very unusual parenting. Star Wars—kid kills him.

In Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Jones is something of a father figure to Short Round, played by Ke Huy Quan, who was twelve but looked about eight. “Every time the camera was just on me, Harrison would be right next to the camera, feeding me the lines and helping Steven [Spielberg] get that performance out of me,” Quan says. (“He was like a mouse,” Ford says, laughing, at the mention of Quan. “Such a baby! A lovely kid.”)

Paul, his character on Shrinking, is a divorced man living in California with a grown daughter in Connecticut. She tries to reconnect with him, in part because she has a child whom Paul barely knows. For most of her life, she says, his work came first. Even now he won’t move east to be closer to her.

He’s sitting at a table in the hangar office, facing giant windows that look out on the runway. I ask him whether, in that fraught relationship on Shrinking, there’s anything he’s drawing on from his own life.

“Um. Yes and no. It is a bit of a shock to discover that there are things that a writer can bring to a script that you recognize as a shadow of your own experience. You don’t necessarily actively draw on some specific thing that happened to you—but it’s in the bank, and you want to spend it.” His voice intensifies, and he’s drumming now. “I mean, you don’t want to take your kid’s life and make that the currency, so you try and separate that. But I’ve got a daughter in Shrinking whose mother said I had spent all my time working, and then when the daughter says she’s going to split for the East Coast, my character says, ‘Well, I’ve got responsibilities here. I have a life!’ And I don’t go with her. That’s the shit that happens, and somewhere there’s a reference in my life and I think, Are they stealing, fucking, my life here? But you discover that you’ve had these experiences, but someone else has, too.”

There’s no point, he says, in going any deeper than that. No point in talking about some specific experience he might have had. “It’s no advantage to having people involved in your everyday life and the nuts and bolts of who you are. Because I’ve never played Harrison Ford in a movie.”

Jessica Williams, his costar on Shrinking, can find herself staring at Ford. “Sometimes watching him do a take is like watching a sunrise,” she says. “It’s like watching Indiana Jones and Han Solo and everything all at once, and you watch it come together and it’s like, ‘Holy shit. He’s that dude. He’s him.’ ”

Ford didn’t grow up watching and loving movies, but he loves the process of making them. John Williams, the legendary composer of the Star Wars and Indiana Jones themes, tells me that Ford will often come sit on an auditorium stage while the orchestra is recording the score, just to listen—an unusual thing for an actor to do. (“A genuine joy,” Williams calls Ford.) I ask Ford whether he has become a film aficionado over time. A movie lover?

He pauses, a long pause. Takes a few deep breaths.

“In a word: no,” he says, then smiles. “It’s not about the movies; it’s about my personal experience. I’m fascinated by how much talent there is out there in all aspects of this business, but I just can’t keep up with the amount of product. I find myself not sitting down to watch a movie every night. We love when we do it, but we do it as a family, so we’re as likely to be watching Poirot the detective as we are to be watching Everything Everywhere All at Once. I’ve got big holes in the fabric, and I don’t consider that to be a positive. I should be watching more, just out of respect for what the business has given me. I love being transported by a movie. A great story. [Drums.] But I do other stuff. I do the dishes instead of watching the movie.”

“You do the dishes?”

“Who the hell else is gonna do it? I gotta live.”

He’s slicing slabs of Emmentaler with the silver cheese knife, and he grabs some wheat crackers from a box on the island. He’s wearing dark jeans, a blue sweater, and slippers. The jeans are crisp but not new, and his shoulders, still broad, stretch the sweater snug. He leads me to the bar in the family room. I ask him (dumbly) if he’s handy around the house.

He looks at me. “I’m a fuckin’ finish carpenter,” he says.

When he bought the house, he says, the doors were cheap, hollow doors and the cabinetry faces were not solid wood, so he assembled and oversaw a crew to fix all that, schooling them on how he wanted everything done.

He pours the bourbon. He sits. The man has some stories.

There was the time he lived on a boat offshore in Belize for the entire four-month shoot of The Mosquito Coast, around 1985. “The hotel in Belize City was super funky and had a very active bar, but no room service. And the bar was nothing but drug dealers and DEA guys,” he says. “So I had this idea that maybe I could live on a boat. A friend of mine helped me find a boat that he’d worked on as a kid, and I lived about a quarter mile offshore. I went to work each day in a Boston Whaler, gave some guy five bucks to make sure it was still there at the end of the day, and then Double Man would drive me to work.”

Double Man?

“Yeah, we used to call him Double Man. I thought it was because he was twice as big as anybody you’ve ever fuckin’ seen. But the real reason was that he was working with DEA but was also available to negotiate product deliveries in... other areas, you know? It was kind of a weird world. But anyway, fishermen would bring me lobsters and fish from the day, and I’d come back to the boat and sit out there and watch the moonlight. It was a hoot. It was just me and a cook, and I had two deckhands, both named Bubba. They both came out of Biloxi. My friend who told me about the boat—it was Jimmy Buffett—he had crewed on it as a kid out of Biloxi.”

Drums his fingers, buh-da-bump, buh-da-bump. Sips bourbon. Story over.

Then there was the time he went to see the Dalai Lama. His second wife, Melissa Mathison, had written the screenplay for Kundun, the Martin Scorsese movie, and they were invited to India. Long story. Couldn’t find the airport... guys with guns... strange hotel. Buh-da-bump. Bourbon.

A Brad Pitt story: Ford had said vaguely in previous interviews that The Devil’s Own was a difficult movie to make. I ask him if he remembers why. “Heh. Yeah, I remember why,” he says, taking a sip, staring down. “Brad developed the script. Then they offered me the part. I saved my comments about the character and the construction of the thing—I admired Brad. [Drumming.] First of all, I admire Brad. I think he’s a wonderful actor. [Thump.] He’s a really decent guy. But we couldn’t agree on a director until we came to Alan Pakula, who I had worked with before but Brad had not. Brad had this complicated character, and I wanted a complication on my side so that it wasn’t just a good-and-evil battle. And that’s when I came up with the bad-shooting thing.”

Ford’s character, a cop, witnesses an illegal shooting by his partner and must decide whether to report it. “I worked with a writer—but then all the sudden we’re shooting and we didn’t have a script that Brad and I agreed on. Each of us had different ideas about it. I understand why he wanted to stay with his point of view, and I wanted to stay with my point of view—or I was imposing my point of view, and it’s fair to say that that’s what Brad felt. It was complicated. I like the movie very much. Very much.”

All these stories. I ask him if he’s ever thought about writing his autobiography. “So.” He swirls the ice in his glass, pours another splash of bourbon for both of us, and tells me that he was once going to but then didn’t. This was just a few years ago. Later, he ran into Elton John at Stella McCartney’s fiftieth-birthday party, and John—who famously wrote an autobiography of his own, Me—asked Ford why he hadn’t gotten around to it. “I said, ‘I thought about it, but I decided I’m not going to do it, because I didn’t want to tell the truth,’ ” Ford says. “And I saw the disappointment on his face—Elton’s a pretty genuine guy, you know. I wanted to mollify him, so I said, ‘But I didn’t want to lie, either.’ So that’s the reason I’m not writing a book: because I don’t want to tell the truth, and I don’t want to lie.”

The cheese is gone. The bourbon is going down smoothly, and it’s to the point where we’re pressing our fingers onto cracker crumbs on the plate.

Ford asks if I have dinner plans. No, I say.

“Okay, let’s finish this shit up and then let’s go out and have dinner.”

That sounds great, I say.

“Great. So where do we have a hole in this story?”

A hole in this story. It’s a thoughtful question and demonstrates a mastery not only of doing interviews but also—there’s no other way to say it—of managing his world. Harrison Ford knows how to get through this life with his self intact. And it’s not just because he’s eighty. He had it forty-six years ago. “We did publicity for the first Star Wars together—we traveled together,” Mark Hamill says. “Harrison was like the father figure. He would give us little report cards after an appearance. ‘You know, Mark, you were a little glib there.’ ‘Carrie, you’re so sarcastic all the time.’ Carrie [Fisher] and I called him the Publicity Sheriff. But more than that, I can’t tell you how many times in my life and my career when I’ve asked myself, WWHD?”

Holes in the story: For one thing, I’ve seen the movie by now—Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny—and it’s spectacular. Except perhaps early on, the first time we see Old Indy. He doesn’t look so good, and it made me a little sad, I tell him.

Ford smiles. “Not what you expected, right? But did you buy it?”

“Absolutely.”

“Yeah. That’s why I wanted to do the movie. I wanted to know what happened to him and how he handled it. [Director James] Mangold and I worked closely together, on that scene especially. Waking up in my underwear with the empty glass in my hand was my idea. I wanted to see Indiana Jones at a nadir point and rebuild him from the ground up.”

That kind of collaboration doesn’t always happen, he says. Now that he has reached legend status, directors listen to him—everyone listens to him, really. Mangold tells me that every morning on set, as the day’s filming began, Ford would rise out of his chair and say, “All right, let’s shoot this piece of shit.” And everyone would laugh.

But back in the day? There was one director, on a romantic war drama called Hanover Street in 1979, who wouldn’t let Ford cut his longish hair even though he was playing a World War II fighter pilot.

“I call us actors just a trick-talking piece of meat,” Ford says. “ ‘Stand there! Say this! Shut the fuck up! I’m the director!’ The guy who directed Force 10 from Navarone invited me to go to dinner the second night. I thought that was really nice. But the first thing he said was ‘If you don’t start doing something, I’m going to send you home. [Looks up at an imaginary waiter.] I’ll have the fish.’ I was a trick-talking piece of meat.”

He drums on the bar. “What else?” He’s hungry. I’m hungry, and feeling a little bourbony.

“I had a moment the other day at the hangar,” I tell him. “I’m sitting there thinking, I’m here with Harrison Ford. He’s being generous and open. Am I making the most of it? What am I not asking?”

He slaps the bar.

“Look, if I had cured cancer last week, we’d have fucking something to talk about. Which is not to say that I don’t—”

He stops, bunches his mouth almost into a smile, and motions his hand back and forth—him and me, there together. He says more quietly, “I mean, I actually love this. I hate it and I love it. Because I get a chance to meet people who do what you do. I have total respect for the process. I just don’t have that much respect for me when I’m doing it, because I’m editor-in-charge of my life. And there are things that are just dumb for me to talk about, that are going to make it less interesting to go see my new movie. Our new movie—Jim’s new movie, Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s new movie, Mads’s new movie, Disney’s new movie.”

“Well, it is called Indiana Jones.”

“Yeah, but I’m not Indiana Jones. I’m Harrison Ford—Harry Ford, in fact.”

“Is that what people call you?”

“No. Well, some people.”

“I’ll keep calling you Harrison.”

“Yeah, well, you fuckin’ better,” he says.

“What kinds of questions do Star Wars superfans ask you?”

“Well, they usually ask me, ‘If there was a fight between Han Solo and Indiana Jones, who would fuckin’ win?’ And I say [voice rising, fingers drumming], ‘Me, asshole! I don’t want to fucking make shit up like that. I mean, what are you asking me that crap for?’ ”

He takes a long sip, tells me to take my time, make sure I have everything I need. I think back to what he said in the hangar the other day, about his life experiences informing his acting and the fact that so rarely has he played a dad. I take a drink and say:

“I want to ask you not about your children specifically but how becoming a parent changes a person. A smart friend of mine once told me something about being a parent, and I think about it a lot: I like to think I’d take a bullet for my wife, but there are two people I can tell you without a doubt I’d take a bullet for.”

He looks right at me, says, “Your children.”

“Yeah. Talk about learning about people, and humanity—you learn how to be afraid. My son’s chronic illness—I bring it to everything I write.”

“Well, how can you not? And I think you can bring it without talking about it. You bring it in another form. You bring it chemically. I mean the—[Table rubbing.] [Long pause.] [Long breath.]—I can tell you this: If I’d been less successful, I’d probably be a better parent.”

He stares at me for a long time.

He has given me material. He knows this—it’s what he’s been trying to do all along. Once again he mentions that Hollywood Reporter interview, which got all kinds of attention because in it he said, “I know who the fuck I am,” which became a sensational headline.

When he speaks again, his voice is not raised, and there is no dramatic tremble, no bite. His voice is peaceful. He says, “I think that’s tantamount to ‘I know who the fuck I am.’ ”

He nods.

“Which I still get shit about from my wife, like I don’t take mental health seriously. I do take mental health seriously. I was trying to say, as I explained to her: It’s that I accommodate all of the flaws that people go to psychiatrists to accommodate, because I accept my flaws. [Drum, drum.] I accept my flaws and my failures—I don’t accept them, I own them. And certainly the more constant gardener is the better parent, and I’ve been out of town, up my own ass, for most of my life.”

We sit at his bar for another few minutes. Everything is still, and he is not rushed. His eyes search the corners of the room, the way I’ve seen them do a thousand times, going back to when I was six years old.

“Hungry?” he asks. He glances at the red light on my digital recorder. “The cost of dinner is to shut that fucking th—”

Story: Ryan D'Agostino

Photos: Ruvén Afanador

Styling: Alison Edmond

Production: Dana Brockman and Robbi Chong at Viewfinders

Set Design: Charlotte Malmlof

Grooming: Davy Newkirk at The Wall Group

Creative Direction: Nick Sullivan

Design Direction: Rockwell Harwood

Visuals Direction: Justin O’Neill

Executive Director, Entertainment: Randi Peck

Executive Producer, Video: Dorenna Newton

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this story misspelled Ke Huy Quan's last name.

You Might Also Like