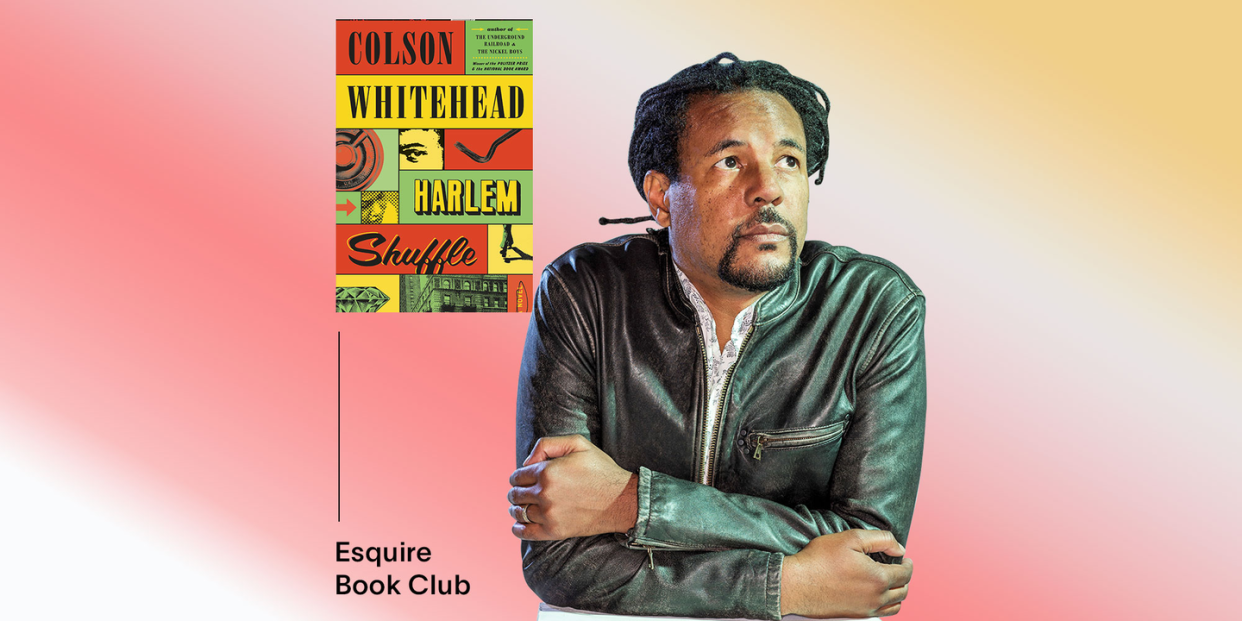

In 'Harlem Shuffle,' Colson Whitehead Masters a New Genre: The Crime Caper

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“It was a beautiful night to be out in the city and up to no good," writes Colson Whitehead in Harlem Shuffle, transporting us to an electric New York City night of bad deeds and big payouts.

These wayward nights are the bread and butter of Harlem Shuffle, a dazzling trip back in time from a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner who never stops reinventing himself. In this noirish crime caper, it’s 1959, and used furniture salesman Ray Carney is expecting a second child with his wife. The son of a notorious small-time crook, Carney has worked hard to become an upstanding member of his Harlem community, but despite his best efforts, Carney is still "slightly bent" when it comes to being "crooked." Carney's upwardly mobile dream of moving to Riverside Drive is expensive, so when his ne'er-do-well cousin Freddie slips him a necklace or ring of questionable provenance, he doesn't ask questions—he just fences the goods through a discreet downtown jeweler. Before too long, Carney is wrapped up in Freddie's risky caper to rob the Hotel Theresa, also known as “the Waldorf of Harlem," but the heist doesn't go as planned. The fallout sends Carney spiraling through Harlem's criminal underworld, where he learns just who pulls the levers of power in New York City, and comes to a reckoning with his double life as a striver and a crook.

Whitehead’s Harlem—“that rustling, keening thing of people and concrete”—pulses with a vibrant heartbeat, evoked through dive bars and greasy spoons and storied Strivers’ Row townhomes. As Harlem Shuffle progresses, Whitehead's lens expands to New York City writ large: an ever-changing metropolis stratified by inequities of race and power, rocked by the protests of the early civil rights movement. In this page-turning novel about how good people come to justify lives of crime, a master storyteller delivers beautifully rendered people and places. Whitehead spoke with Esquire by Zoom to discuss masterminding his own heist, researching a bygone era of Harlem, and how he expects the pandemic will change New York City.

Esquire: Where did this novel begin for you, and how did it take shape over time?

Colson Whitehead: It was about seven years ago. I was thinking, “Maybe I'll rent a heist movie tonight. Heist movies are so fun. Could I write a heist book?” I gave myself permission to do that. But I was about to start writing The Underground Railroad, so I put it off. When my schedule clear again, The Nickel Boys seemed more compelling, given where we were after Trump was elected. Should I be hopeful or pessimistic about where the country was headed? So The Nickel Boys seemed the more compelling project to pick up in 2017. But when I finished that book, I had all these notes for Harlem Shuffle that I’d tucked away, so I got started really quickly. It’s a very different book than the last two. It was sort of a relief, considering how grim some of the material in The Underground Railroad and The Nickel Boys was.

ESQ: What’s your personal attachment to the heist genre? Are there any heist movies or books that were lodestars for you as you wrote Harlem Shuffle?

CW: I grew up watching a lot of TV—I loved Saturday afternoon matinees of like The Taking of Pelham One Two Three and Dog Day Afternoon. As I got older, I saw earlier classics like Rififi, Asphalt Jungle, and The Killing. Those are all very low technology heist movies as opposed to, say, Heat or Ocean's 11. These guys are not renting million-dollar electromagnetic pulse machines to knock out the casino security cameras. These are guys who are really getting sweaty trying to pull it off. I read a book about poker a couple of years ago; I learned about how there's an attitude of gamblers where the next hand will change their lives. If they just get this full house or royal flush, they'll transcend their grubby, mediocre existences. When you plan a big heist, you have this similar hope that if you can pull it off, just bring all the elements together and plot and plan, you can escape your mediocre existence. Something about that was appealing to explore.

ESQ: That's such a great point about the technology. In a movie like Ocean's 11, it's so much less character-driven in that the million-dollar technology is what rules the day. Whereas in a book like Harlem Shuffle, characters have to rely on their smarts and interpersonal skills to get the job done.

CW: Also, a heist movie is generally full of incompetence. In Ocean's 11, everyone is really good at their job. In a more classic heist movie, the viewer knows that the wheel man is getting high the day before, or the safecracker found out about his wife's affair and is really distracted. They’re good at their jobs, but something's going to go wrong. A plan is something that has to be executed by flawed human beings.

ESQ: The heist you create is so gripping. How did you game out the heist, and make sure it was plausible? Did you have to learn to think like a criminal?

CW: I outline my books, which is sort of the same thing—a lot of moving parts. I know what I'm trying to accomplish, so how do I get there? I knew that there would be readers looking at this heist and saying, “That doesn’t work. In 1964, hotels didn't have that kind of safe deposit box.” Because of that, I had to really do the research. I found a good model in the Hotel Pierre heist that happened in the early seventies. That's where I got the knowledge of how you break into the safe deposit boxes. You've got to take care of the elevator guy, the guests—all these different variables. My heist is a smaller scale, but you do the research in the hope that you don’t screw it up so much as to get angry letters.

ESQ: What drew you specifically to this setting, and how did you strive to evoke it authentically?

CW: I’m always committing to a time and place, and I have to make it real. Before I had characters, I knew I wanted my robbers to have their heist unfold at a time of city calamity, like the blackout of 1977, or the Harlem riots of the early 1940s. Ralph Ellison used the riots in Invisible Man, so he kind of owns that. But the 1964 Harlem riots, which I was aware of dimly, seemed like something my robbers could use to hide their crime. Then, I had to make it real.

With The Underground Railroad, I learned just how useful primary sources are. To write Harlem Shuffle, I turned to memoirs of gangsters or gangsters' wives. Bumpy Johnson was a famous Harlem criminal. I wanted to put him in the book, but he was actually in Alcatraz at the time the book was unfolding. His ex-wife has a memoir detailing how the whole operation worked. I got a lot of how these secret criminal organizations and rackets worked from memoirs. I went to the New York Times archives to find out what was happening in 1961 in the city. “Robert Wagner is getting reelected. Can I use that for something?” The newspapers also contained full-page ads for furniture, so I would steal the language of the furniture ads.

I don't like leaving the house for research, and luckily, I live in a time where I can get a lot done from home. If you go to YouTube and put in 1960s Harlem, you’ll find that amateur photographer from 1963 has uploaded his 8mm travelogue of 125th Street. From there, I can see how much a dozen eggs costed, what kind of hats were they wearing, what kind of cars were they driving, and other important details. It’s all about finding those primary sources, stealing what I can from them, and hopefully deploying those facts in an artistic way.

ESQ: That's something that stuck out to me about Harlem Shuffle. Its texture and vividness arises in part through how you evoke the characters’ material lives: what they're wearing, what they're eating, what the real estate looks like. We can practically see and feel the furniture in Carney’s showroom. You write, “There was a natural flow of goods in and out and through people's lives, from here to there, a churn of property.” That churn is so real in the novel.

CW: That’s the energy of the city. The churn of envelopes in and out of corrupt people's hands. The flow of home goods, or used and stolen jewelry. There’s also the ebb and flow of neighborhoods. Harlem was German, Irish, Jewish, and Italian. These folks came to America, lived there first, then became middle-class and moved on. A new wave of immigrants from the South, the West Indies, and the Caribbean came in to replace them. That’s the energy of the city, this constant churn and renewal.

ESQ: Your fiction is often populated by people with unusual jobs, esoteric jobs. Elevator operators, nomenclature consultants—now, you’ve turned to low-ranking criminals. What about these sorts of jobs is intriguing or narratively fruitful for you?

CW: I'll come across an article about, say, corporate namers, and think, “That’s an interesting job. What do they do?” Then it stays with me. With The Intuitionist, I saw a Dateline NBC report on escalator inspectors. I thought, “Who is that guy?” In fiction, it became elevator inspectors. I get ideas from magazine articles, TV shows, and just walking down the street. I love to find something I never thought about. A fence, in the case of Ray Carney. Even the cleanup crews in Zone One: the zombie janitors. If there's apocalypse, and the apocalypse ends, who cleans up? Who are those people? I find these weird jobs to be very fruitful avenues of investigation. If it's the right thing, if it stays with me, and I keep coming up with more details or speculation I want to pursue, it can become a story idea.

ESQ: Harlem Shuffle is the latest entry in this groove you've gotten into of writing fiction set in the past. What draws you to writing about the past?

CW: My first couple of books were very contemporary. John Henry Days is about internet culture in 1996; Apex Hides the Hurt is about corporate naming. Zone One is very much about living in New York right now in our contemporary consumer society. I really felt that I’d said my piece. I don't have anything more to say about Information Age culture and how we live now. Going back to the past, I've found different stories to tell. I get to use different muscles in research, but also in recreating the psychology of the characters of that specific period. Also, there are stories that have not been told. Have there been a lot of stories about fences? I have no idea. Not when I started looking six years ago. But has there ever been a story about a Black fence? I'm pretty sure not. With The Nickel Boys, the story of those terrible reform schools was unknown. With stories about the past, I get to have something that has not been explored before in fiction. In the case of The Nickel Boys, I get to pay tribute to the survivors and those who died there. It’s different than writing about web 2.0 or web 3.0.

ESQ: One of the most fascinating things about Harlem Shuffle is the novel’s interest in the divided self, or the compartmentalized self—the ways we cordon off parts of our personality and our identity. You write of Carney, "He'd spent so much time trying to keep one half of himself separate from the other half, and now they were set to collide. But then—they already shared an office, didn't they? He'd been running a con on himself." How accurately does Carney see himself?

CW: He's running a con on himself. He deceives himself about how much he likes the crooked lifestyle. People tell him he’s a fence, and he says, “No, I just sell gently used goods sometimes.” When really, he’s just selling stolen goods. Part of the arc of the book is him accepting, rejecting, and ultimately embracing his criminal side, which is his natural inclination. He does know who he is. But he's not going to say it out loud.

ESQ: Is that fun, writing a character with a disconnect between the stories he tells himself and the stories he tells publicly?

CW: It's a shade of an unreliable narrator, where the story he's telling the reader isn't necessarily the truthful one. He knows where he's dealing in falsehoods. It’s definitely fun. When I was doing research, I learned about how a fence is this conduit between the straight world and the crooked world. The job is mediating between two different worlds, and so that sort of bled into his divided psychology.

ESQ: Harlem Shuffle has a lot to say about how people come to be involved in crime, and how they justify that lifestyle to themselves. Why does Carney keep getting sucked back in, almost but not quite against his will?

CW: He would very much not like to live in the house he grew up in. He doesn't want to be a criminal. He doesn't want to live like his father, who was a petty thief. He wants a wife and kids and all those middle-class trappings that were denied him. But he is who he is. For me, that's very interesting and dynamic: following who you want to be versus who you actually are. Eventually, his eyes are opened to how things actually work in Harlem and in the city. Everyone's crooked. Everyone's trading envelopes. You pass all these storefronts every day and don't know that there's a craps game in the back. Everybody's cooking, except for his wife and kids. So why not? There are so many different degrees of how bad you can be. To him, he’s nowhere near as bad as someone like Miami Joe.

ESQ: What was it like creating a small-time villain like Miami Joe, coming off of creating some toweringly evil villains in your previous novels?

CW: I see Harlem Shuffle as three novellas that come together to make one novel, so each one has its own villain. None of them are as fearsome as the slave catcher in The Underground Railroad, but I wanted to have fun with the genre, and have these colorful villains who are great foils for Carney, but also formidable antagonists in their own right. Whether it's Miami Joe or the banker or the villains in the third section, finding people who could test Carney was important, but they also had to fit into the colorful menagerie I was creating.

ESQ: Carney wants to leave his dubious past behind, but as the novel progresses, it becomes clear that the respectable world is governed by some of the same principles as the crooked world. You write, "Plenty of crooks were strivers, and plenty of strivers bent the law." The back cover describes the novel as a morality play, yet in some ways, with the bent world and the straight worlds overlapping, the novel is almost morally neutral. Can you expand on how you see the novel as a morality play?

CW: I'm pretty neutral on all these different characters, and I think the narrator is too. Carney judges the people he meets, for his part. What I like about the three-part structure is that in the first part, I can introduce the players and the rules of the world in Harlem in the late fifties. In the second part, I can pull back and look at this other dynamic in terms of class and corruption. In the third part, I can pull back again to bring in Wall Street and Park Avenue—to really see how the city actually works, not just the corner of 125th Street. Different people are in their own grooves in terms of where they fall on the moral-immoral spectrum. I think the narrator has a neutral stance.

ESQ: You finished this novel during the beginning of the pandemic. What was it like to write a story featuring a robust, lively New York City during a time when the city was so hollowed out?

CW: I finished the novel in May 2020. When lockdown happened in March, I was already on the final descent, so I was really bringing it in for a landing. Often, what I'm writing has nothing to do with what's happening in my life. I have to get in the character and that's just the way it is. It was odd, finishing the book and the George Floyd protests happening the next day. I had just wrapped this description of the aftermath of a big protest, and then we were back in the same discussion about police brutality. That was weird.

Zone One is about a pandemic and an emptied-out New York. It felt more eerie being the author of a zombie apocalypse novel than the author of Harlem Shuffle. I didn't realize how important toilet paper would be in the apocalypse. My imagination failed there. I could never foresee that some people would be like, "The zombie virus! It’s just like the flu. You get over it.” Or, “I’m not taking any zombie vaccine!” Lockdown was weird because I'd written an apocalyptic New York novel, more so than Harlem Shuffle.

ESQ: So many writers have reported that these past eighteen months have been very challenging for them creatively. How has this time affected your creativity?

CW: In terms of writing, I’ve been more productive. I was able to finish the book once I figured out getting the kids on internet classes, and then when I finished the book, I started writing more Carney stories set in the 1970s. I just kept going. it's been really productive, and a great thing to have in my life. However, my leisure reading has gone down to nothing. I can only read crime stories, memoirs, or nonfiction about New York City. My attention span has taken a real hit. I can either watch TV or read stuff for work, but I can't read for fun. Hopefully now that we're inching closer to normality, I can get back to that.

ESQ: The ending of the novel is so gorgeous and poignant. You pan out to capture the constant change, churn, and reconstruction of New York City. It reminds me of the essay you wrote in the New York Times almost twenty years ago, two months after 9/11, about your private New York. That essay and the ending of Harlem Shuffle seem to share some thematic DNA. Post-pandemic, is your private New York changing once again? How do you anticipate that the city might change more broadly?

CW: To me, that essay is about superimposing your idea of the city on the city itself, but also looking back at your previous selves, and all the things that have occupied the same space. That’s definitely how I relate to the city. Downtown New York is Cortlandt and Greenwich and Radio Row, and then it's a crater. Then it's the World Trade Center. Then it's a crater, and then it's the Freedom Tower. All those lost histories of New York, and we're making new histories at the same time. How I perceive myself and my past is tied up in how I perceive the city.

I did a lot of location scouting for this book, and then for the second Carney book. I never really knew Upper Manhattan. My first house growing up was at 139th and Riverside, but I never knew Washington Heights. I never knew East Harlem. As I find places for Carney to have adventures, I’m getting this new New York, and it's been great. When I couldn’t go to stores and restaurants, all I could do was be outside on the sidewalk. Being outside was part of what kept us human. It allowed me to rediscover the city.

I don't know what kind of art will come out this. There’s a new sincerity, like Ted Lasso—everyone's sincere now. That's what they said after 9/11. But I remember being outside last year thinking about how the streets are empty. There are more people on the street who have mental illnesses. The city is dirtier. It reminded me of the anxious New York of the 1970s. Out of that terrible time when the city was bankrupt and crime was at an all-time high, we got disco, punk, and New York salsa. It was a time where the city was a terrible place to be, but the writers and artists and musicians found a way to use that and make something new. I don’t know how we can characterize post-pandemic art, but New York is always coming back and bouncing back. That’s because of the people. Whether it's the teachers or doctors, bus drivers or artists, we’re all forced to confront what's happened to the city, then dig deep and rebuild in our various ways.

You Might Also Like