For Grady Hendrix, There's No Place Like a Haunted Home

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

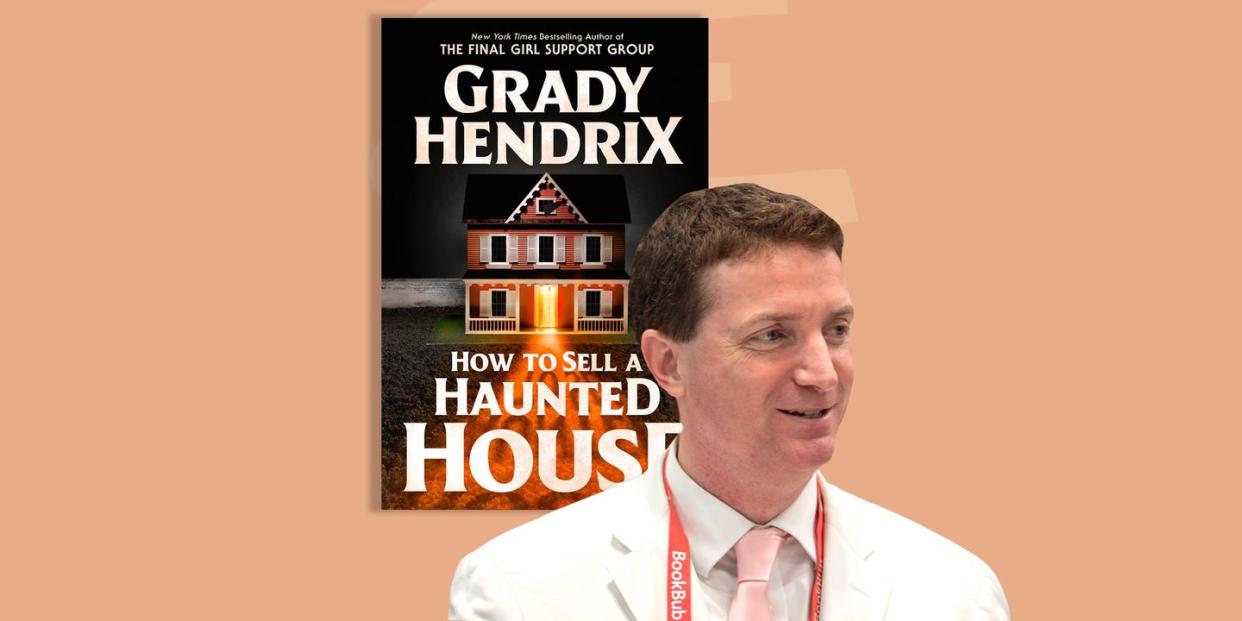

Grady Hendrix is a skilled performer.

Before you even read a word of his fiction, flip to the back cover and check out the author photo. In a blinding-white suit, holding a (presumably?) fake human skull, Hendrix gives off strong Southern-undertaker-doing-community-theater-Hamlet vibes. It’s an eerie and disarming aesthetic. You are drawn to this man, amused even, but there’s something sinister around the edges…

Hendrix plays the role of horror’s clown-prince, and he does it with style. He has replaced ‘boring’ book readings with an immersive one man show. And when he speaks to interviewers, it’s with a soft, excited voice, completely at odds with the turns that the conversation often takes. Talking with Hendrix, it’s easy to wander deep into discussions of conspiracy theories or serial killers, without realizing how macabre the conversation has become.

His books lull you in much the same way. He has a penchant for the quirky title and a creative spin on classic tropes. In a decade of writing, Hendrix has toyed with haunted homeware stores (Horrorstör), demonic possession (My Best Friend’s Exorcism), satanic pacts (We Sold Our Souls), vampires (The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires) and the slasher movie (The Final Girl Support Group). Each may sound like satire, but the irreverence—like the white suit and skull combo—is camouflage for a deeper interest in human drama. “I really like people,” Hendrix says, “and I like horror, because it’s not boring. Horror can say directly what mainstream culture tries to say obliquely.”

Now, in How to Sell A Haunted House, he’s taking on perhaps the most fundamental horror tradition of all. The novel follows Louise and Mark, estranged adult siblings forced to work together to sell their childhood home following their parents’ sudden death. When clearing out the house, however, they find that some things do not want to leave. What follows is classic Grady Hendrix: an authentically frightening, genuinely funny reconfiguration of what a haunted house can be. It features demonic puppets, invisible dogs, and good old skeletons in the closet. At its core, though, it’s about hearts. Broken ones.

When Hendrix joins me via Zoom from his home in New York City, he’s as ebullient as ever. We talk about performances and masks of many kinds. There is a sense, though, that Hendrix is ready to wear his own heart a little more visibly.

ESQUIRE: Hi Grady, congratulations on How to Sell a Haunted House. That’s a very Grady Hendrix title.

Grady Hendrix: You mean ridiculously long and no one will remember it? I agree. It’s on brand.

Compared to The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, it slips off the tongue. But, speaking of your brand, How to Sell a Haunted House is another book in which you tackle an existing horror formula either through parody, deconstruction, or redeployment. Are you intentionally trying to work through and rewrite the entire horror canon?

Well, yes and no. What I’m intentionally trying to do is pay my mortgage. But I really enjoy taking something that has become familiar and a little shop-worn, and trying to rediscover what was scary about it in the first place.

amazon.com

$19.60

amazon.comA lot of it goes back to Alan Moore. I was a huge fan of his Swamp Thing comic books, particularly the American Gothic run, which is where he takes Swamp Thing on this road-trip across the US. In each issue, he encounters another classic American horror trope, but in a different guise. Vampires, but they are underwater sex vampires. Werewolves, sure, but Moore makes an early connection between lycanthropy and menstruation cycles and looks at how women were treated in that era. I think those comics are what first showed me that there is still a lot of power in these old ideas. If you can just bang off the rust, you can find something powerful and souped-up under the hood.

One of the ways that you “bang off the rust” in How to Sell a Haunted House is by putting the financial implications of a haunting front and center. It’s something that often gets overlooked in these types of stories. Why did you choose to confront it?

I’ve been playing with haunted houses for book and movie ideas for a long time, and the response I always get from editors and producers is that key question: “Why don’t people leave?” In classic William Castle movies, it used to be that the door was locked so no one could get out, or there was a prize of one million dollars if someone could last the night. I would always argue that it was much simpler in reality: you can’t afford to leave.

A book I wrote but never published was all about a family who make an aspirational house move and when they discover their house is haunted, their only solution is to ignore every single hell-mouth thing that is going on. But every time the pushback I get is that no one will buy that response. So even though I think the money is a factor, and I’ve heard from people that it’s a factor in their lives, no gatekeeper will let you use that financial angle. With this book, I finally found the thing that flipped it. There is something about fighting over a will that people understand, even when they can’t comprehend not being able to afford to move house.

You could argue that the pushback says more about media executives’ salaries and bonus structures…

True, but I know a lot of people who… okay, maybe they aren’t living a marginal existence, but they don’t have a lot of money, and they would also say, “That’s garbage, I would leave right away.” It’s very hard to live that reality in the abstract, to face that money would keep you in place, even if your family was in danger. I can’t wait for Mike Leigh to make a haunted house movie and answer this question.

This book is so thematically centered on grief and loss, and I know you wrote it during Covid lockdown. Is there some interplay there, between your writing and the surrounding events?

Oh absolutely, and there is a good side and a bad side. The good side is that I wanted to write about an imaginary family because I missed my own. The darker side is that my mom had a health scare during Covid, and I went down to South Carolina to stay with her while she got back on her feet. I remember going out to her garage and seeing all this stuff. I thought “Oh God, if she dies, I’m gonna have to clean out all of this crap!”

When someone dies, there is so much stuff. It’s such a kick in the teeth to go through this enormous loss and then have to clean out a house. Those objects may mean nothing to you, but they did to the person who has gone. They feel like the last fingernails digging into this physical plane. As you throw them out, you’re prying away that person’s presence. It feels like you are erasing them. After all, what is a ghost but something left behind? Often it’s a house you grew up in too, which is an added emotional weight. Sometimes the world just asks too much of people.

Am I correct that the book is inspired by your own family home?

Absolutely, but not in fear, in comfort. One of the luxuries of writing a book is that you get to hang out somewhere imaginary for the best part of a year. I sometimes indulge a little and choose to set my book somewhere I find comfortable. My aunt’s house, which this is based on, was a place we spent a lot of time growing up. We had all our family get-togethers there. It was so comforting to me. Spending some imaginative time in that house was a comfort blanket for me during the pandemic.

That perhaps explains your comment in the foreword that “nothing is more comforting than a haunted house story.” Whereas I can’t think of anything more discomfiting.

Well, haunted house stories go all the way back to ancient Athens. They are at the core of the human experience. They are central to our identity and our sense of safety. So, the fact that they are the site of hauntings makes total sense to me, because what’s the difference between a ghost and a memory and dream? These are slippery categories that slide over each other, and houses contain each of those things.

That’s a very Freudian approach. I’m sure that Freud would have a number of things to say about the other elements of the novel, especially the dolls and puppets.

It is all very Freudian. You start with Freud’s theory of The Uncanny, which is at the basis of hauntings and ghosts, and that takes you straight into the concept of the Uncanny Valley. It’s a place where automatonophobia dwells, that fear of something that looks human, but isn’t quite human. Houses and dolls live very close together. We all grew up with stuffed animals, dolls, action figures. Those are the things that surrounded us growing up… in our homes.

amazon.com

$12.99

amazon.comBut these are especially creepy puppets and dolls. One in particular, an heirloom of sorts called Pupkin, is an agent of absolute chaos.

I’m really glad you used that word, because in puppetry, there is a huge difference between hand-puppets and marionettes. Marionettes have a dignity and grace to them. Hand puppets are chaos and disorder. Mr. Punch is a hand-puppet, after all. They bring anarchy, that’s what they do. Puppets have the power of dolls times ten. Even if you just take your sock, pull it over your hand, draw a little face on it, and play around with it for five or ten minutes. Then ask yourself: where is the will coming from that moves my hand? You have split yourself into two beings and it’s a really weird state. I think as humans, we’re wary of things that bend our brain that way.

Is that why dolls are so regularly presented as fearful objects in horror stories?

Someone once said to me that dolls are the only inanimate objects that can make eye-contact. There is something very disturbing about that. I think it fires off a reptilian part of our brain—the part that looks for symbols and tries to make patterns in the dark. We invest dolls with power all the time, right? They are one of the few things that get their own entry in the ten commandments. No graven images. Sure, that’s about worshipping other gods, but I think it’s also a warning not to make a doll that you’ll get too into.

Masks are similar. All over the world, in different religions and cultures, people use masks to invoke some kind of trance state. The idea is that you put on a mask and you become open to possession by something else. Certainly, when I’ve done mask work in the past, it gets to the point where you wonder, “Am I wearing the mask, or is the mask wearing me?” Likewise, when I used to do drag clubs, I was more fearless, more liable to put myself into ridiculous situations, because you feel like it’s not you, it’s this persona, like a force-field protecting you from harm.

You include a lot of similar theories in this novel about puppetry, theater, and mask-work. Is that your invention, or is it rooted in existing culture?

The first sentence that Mark says in that section is, “I used to belong to a radical puppet collective.” For a while, I too belonged to a radical puppet collective in the nineties. We were very political. Similar to the scene in the book when Mark’s group puts on a 9/11 show for fourth graders, we had no business putting on a puppet show about the Pinochet regime to kids of a similar age. That’s the reason that a lot of authoritarian regimes in history, from Mexico’s socialist government to Nazi Germany, one of the first things they cracked down on were expressions of folk tradition, which tend to be subversive. Puppetry and puppet shows are usually one of the first to go.

That scene you mention, in the classroom, is one of a number of darkly funny moments. Though How to Sell a Haunted House is full of somber moments and scares, I also think it’s your funniest book.

Well good, because the book is looking back on the character’s early twenties, and that’s a time when you take yourself really seriously. But the thing is, with a little bit of perspective, so much of our lives are ridiculous. We spend so much time worrying about stuff and having these arguments, then five years later, we think, “What the hell was that about?” To an outside observer we all look like lunatics.

Although it’s funny, it also feels more heartfelt than your previous work. You’re still deconstructing tropes, but there’s real emotion at play. Is it fair to suggest that you’re moving away from your trademark irony?

With every book I write, there are two things going. One is a question I’m trying to answer—in this case, trying to figure out what happens to a family when our parents die, and our weird relationship with inanimate objects. But with every book. I’m also trying to set myself up with a technical challenge. I had never written first-person before The Final Girl Support Club; I’d never written lyrics before We Sold Our Souls. With this one, I was setting myself the challenge of trying to write convincingly about a family, rather than just one person. Families are hard, because everything is back-story and subtext.

amazon.com

$14.39

amazon.comThat’s a long way of saying that I’m always trying to get better. Because if you’re not, what’s the point? So it’s great to hear from you that you think the books are more heartfelt, because that means I’m moving in the right direction, and giving readers stuff they really want to read about. Irony is pretty cheap and it’s going out of style real fast.

You had some cinematic success this year with the adaptation of My Best Friend’s Exorcism, which is a book your fans love for its blending of the heartfelt with postmodern references. Are there more movies to come?

Great news. Charlize Theron is still involved in adapting The Final Girl Support Group for an HBO show. They’ve got a showrunner and a pilot script and they are in the final throes of thrashing out that script before moving forward. Andy and Barbara Muschietti, who adapted Stephen King’s IT, are onboard to produce and direct the pilot. The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires is also at HBO. I’m going to be involved in that one pretty deeply. And Horrorstör is going to be a feature film. I’m writing the screenplay and we have a director onboard, though I can’t say who it is yet. After twenty-two drafts, we finally have a finished script and we’re really hoping to make an announcement soon.

So, there’s lots of stuff going on, but it’s Hollywood, man. We’re like salmon spawning—only a few of us make it to the finish line. The rest of us get eaten by bears.

You Might Also Like