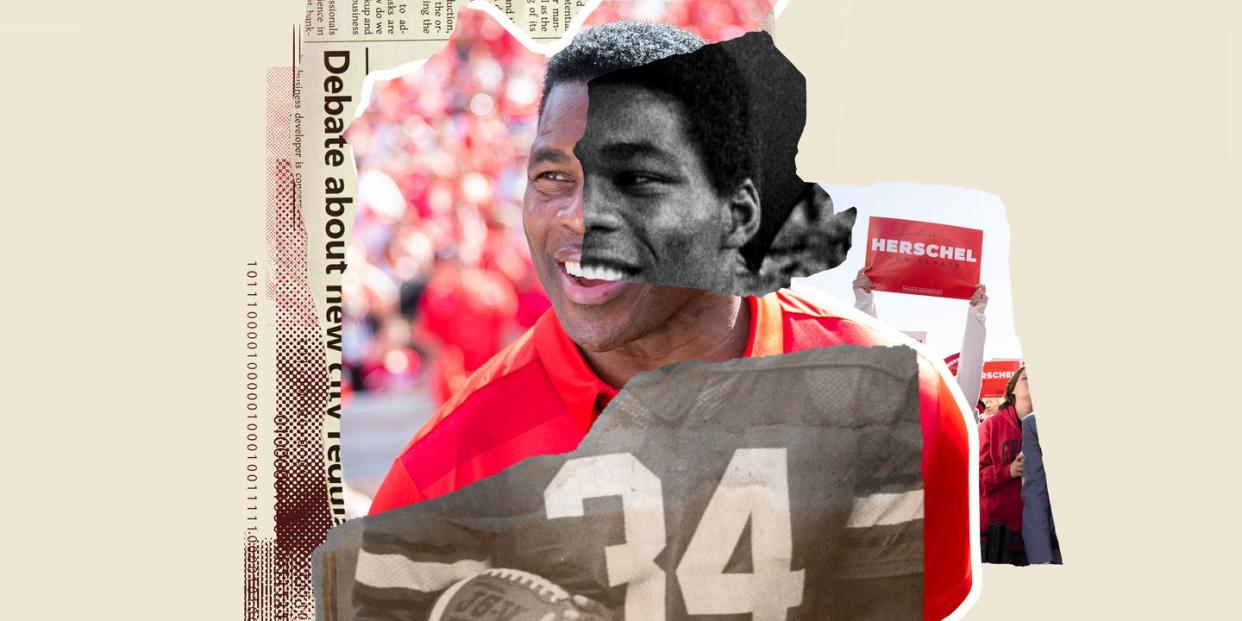

My God, Herschel Walker, What Have You Become?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Is Herschel perfect?” the man in an American-flag suit and long white hair asks.

We gather together this Election Night, November 8, 2022, on the ballroom floor of the Omni Hotel, in Cobb County, outside Atlanta, to await the results: Senator Raphael Warnock versus Herschel Walker. The country keeps one eye on Georgia tonight. I’m anchored near the podium, next to the roped-off VIPs and Don Knobler in his red, white, and blue. Everybody wants pictures with Don. The VIP of the VIPs. The VIP for the People. Imagine if Santa collided midair with Evel Knievel and from the smoke and wreckage emerged a gregarious Dallas real-estate mogul.

Don says he and Herschel ride motorcycles together back in Texas.

“Am I perfect?” Don says and laughs wistfully.

Don was once ejected courtside from a Mavs game for telling Patrick Beverly to go fuck his mother.

“Are you perfect?” he asks and puts a hand on my shoulder.

Don squeezes my shoulder and raises a finger to his lips.

“But Jesus?” Don says and arches his eyebrows over his star-spangled glasses. “Jesus is good.”

No argument here, but I did want to hear more about those motorcycles as Don is whisked back to the podium, where a portly couple patiently wait.

I am the only one here with a tattered copy of Herschel Walker: From the Georgia Backwoods and the Heisman Trophy to the Pros, by Jeff Prugh. It is a child’s book. I did untold book reports on it at DeKalb Christian Academy (the Crusaders), an extinct evangelical private school in Atlanta.

My lifelong Herschel fandom is not enough to bring me to the podium tonight. When Walker was thirty-nine, he received a diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder and spent three weeks at Del Amo psychiatric hospital in Torrance, California. In 2016, I spent three days at Wesley Woods Hospital at Emory University for depression and suicidality. I was thirty-nine years old.

I wanted to hang with Herschel today, as improbable as it might seem. A long shot. Miracle required. But Herschel Junior Walker is a long shot, a miracle, too. I want to talk about mental health and profile this historic night. I’ve called, emailed, and texted Walker’s Deputy Campaign Manager, using the name of this magazine, but no luck. (Mallory, your voice-mailbox is full.)

Near the podium, I’m asked by families, groups of friends to take pictures. I oblige. No prompting required. Everyone smiles big. Thumbs up. The podium bears the sign: HERSCHEL.

Herschel Walker is a pioneer in American politics. He is the first Senate candidate to admit to a mental illness and provide a narrative of his own cognitive chaos. In his 2008 book, Breaking Free, Walker describes his use of twelve different alters to deal with trauma from youth. Chubby, stuttering, he was picked on. The dark scared him and trees in the night.

The two huge ballroom TVs flash HERSCHEL and the DJ cues the Who’s “Who Are You?”

Who…who…who...who?

I do the tight-smile thing and look around, but folks just jam along. It’s 8:04. Polls have been closed for an hour. Don poses with three radiant and robust senior ladies.

In Breaking Free, Walker opens by nearly pulling a gun on a car salesman. Toward the end, he puts a gun to his own head. Russian Roulette. On your Chekhov Loaded Firearm Scorecard, that’s two.

I take a picture for newlyweds. They’re University of Georgia grads. (Me too! Go Dawgs!)

During the campaign, more guns to more heads emerged. On September 23, 2001, Walker threatened his wife, Cindy, with a gun and spoke of a shootout with police before his therapist, Dr. Jerry Mugazdae, intervened. Police seized a SIG Sauer 9mm and placed his address on a caution list because of his “violent tendencies.” Months later, a former Dallas Cowboys cheerleader reported Walker lurking outside her apartment. As part of a 2005 protective order, Cindy reported Walker holding a gun to her head and threatening “to blow your fucking brains out.” In an affidavit signed by Cindy’s sister, Walker also told Cindy’s boyfriend he wanted to “blow their fucking heads off.” According to a 2012 police report, when Myka Dean wanted to end their twenty-year “on off” relationship, Walker threatened to wait outside her apartment and “blow her head off” and then his own. Mallory has told the press of Dean’s allegations that Walker “emphatically denies these false claims.”

I snap two shots (vertical, landscape) of a family of four. The youngest wears a UGA cheerleader outfit.

In the early 2000s, Herschel was not the only ex-footballer handling loaded guns. Mike Webster kept guns. Justin Strzelczyk pulled a loaded gun at a bar in 2000 while talking politics. Andre Waters, Dave Duerson. Ray Easterling, Junior Seau. All used handguns to end their lives. Javon Belcher shot his girlfriend and himself in the Chiefs parking lot. A few miles from this podium, former UGA defensive back Paul Oliver put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger. Aaron Hernandez was found guilty of murder. In Rock Hill, South Carolina, Phillip Adams shot six, including two children, before killing himself.

Each player had brain damage. Each had CTE. The disease can only be diagnosed postmortem.

A father and son pose with Don, who is joined by his lovely wife, Damaris.

“I’m still struggling with the knowledge that I have a mental illness,” Walker says in the author’s note to the book, “and making sense of my life knowing what I know now remains a real challenge for me.”

A group of four Chinese ladies pose in front of the podium. The tallest, whom the camera loves most, wears designer jeans and a red LETS GO BRANDON T-shirt that really pops with her long hair and candy-apple lips.

I prefer this side of the camera. At DeKalb Christian Academy, GOP advance teams used to stage our classrooms for campaign photo ops. In 1988, Fourth District incumbent Pat Swindall, who’d been found guilty of perjury in a home-loan, Colombian-drug-money-laundering scandal, shook our hands and tousled our hair. News cameras filmed our field trips to the state capitol each January at the Right to Life march. We walked beside nuns and priests who held plastic fetuses in jars. Parents hoisted posters with images that proved a real bummer to our paper-bag lunches of PBJ and Cool Ranch Doritos.

Newt Gingrich, son of Georgia’s Sixth District, put it this way about Walker on Fox News: “He’s the most important Senate candidate…because he’ll do more to change the Senate just by the sheer presence, by his confidence, by his deep commitment to Christ, by the degree to which he has—you know, he’s been through a long, tough period. He had a lot of concussions coming out of football. He suffered PTSD.”

What would the presence of Herschel Walker represent in the U.S. Senate?

A potential voice for those facing or recovering from mental-health issues?

A painful symbol to victims of domestic abuse?

A reflection on the permanent woozy state of our body politic?

I’m not sure. But here in the ballroom and back at the bar, only one soul recalls what I can’t forget.

Under the moonlight, my father split wood as Georgia trailed Tennessee 15–2. September 6, 1980. My dad, a Hoosier from southern Indiana, had cleared pines for a backyard basketball court along the woods of the South Fork Peachtree Creek. Larry Munson’s voice crackled on the radio. A voice of cigar smoke, fishing cabins, World War II dispatches. Third quarter. Getting late. Sixteen yards to the goal, Georgia turned to a freshman.

We hand it off to Herschel and there’s a hole…5, 10…12…he’s running over people. Oh you Herschel Walker. My God almighty he ran right through two men. Herschel ran right over two men.…My God, a freshman.

My father kept that last pine stump in the ground. A marker. The revelation. Walker catapulted Georgia to a comeback, an undefeated season, and a national title over Notre Dame in the Sugar Bowl. Watching Walker soar over that Sugar Bowl pile for a touchdown is my first memory. A memory that merged with the pine stump and sixteen improbable yards. We took the mythic where we could find it. And every day I took a Nerf football and leapt over the back of our sofa in tribute to Herschel. The landing was soft, but if I needed harder proof, there was the spot out back where lightning struck. My God, Herschel Walker.

Georgia attorney general Chris Carr remembers. He recounts Herschel’s run in Knoxville and the Over-the-Top Sugar Bowl TD in his opening speech. Before the ballroom opened, I polled GOP state senators and politicos at the bar to see who could accurately recall Herschel’s two most famous TDs. (Few, few.) But Carr remembers. He admits to getting in trouble for excessive sofa TDs. A true believer. AG Carr! My man.

Carr takes a seat near the VIPs. I introduce myself as a writer working on a Herschel Walker story and fellow sofa hurdler. Carr laughs and we shake hands. He smiles like a man who has won a hard victory. We’re UGA grads. (Go Dawgs!) I tell him of my polling research. Carr chuckles and says he actually grew up a Notre Dame fan. He was born in Michigan and his family is Catholic. I laugh and compliment his good sense in tailoring a speech and share my own Yankee roots. Our banter alerts a member of his party who makes introductions and our talk flattens.

The election results play on Fox News. Carr’s wife served as the former chief of staff for Kelly Loeffler, who lost to Senator Warnock after being investigated for insider trading during the early stages of the pandemic. (The U.S. Department of Justice and the Senate Ethics Committee later cleared Loeffler.)

Carr navigated his own political obstacles as AG. He renounced the Texas AG’s lawsuit against Georgia that sought to throw out votes and help swing the 2020 election to Trump. Carr’s office claimed the lawsuit was “constitutionally, legally, and factually wrong.” Trump endorsed Carr’s primary opponent. Carr prevailed.

His role as chairman of the Republican Attorneys General Association (RAGA) received scrutiny. The fundraising arm of RAGA, the Rule of Law Defense Fund (RLDF), sent robocalls in early January 2021 to supporters of President Trump to march on the Capitol to “Stop the Steal.” Before resigning from RAGA, Carr denied knowledge of the calls and condemned the riot, and Georgia certified the election results.

Rosanne Boyland answered the call. The thirty-four-year-old woman from nearby Kennesaw followed the theories of QAnon. (President Trump was set to stop a satanic cabal of child traffickers run by Wayfair, Dems, and Hollywood stars.) She traveled to D.C. and stormed the Capitol. Repelled by tear gas, she was killed in the retreat. The official cause was amphetamine intoxication. (This active ingredient was also in her ADHD medication.) But witnesses and video suggest she was swept up by the crowd and caught under the tangle of bodies.

Carr takes his seat and I go back in front of the podium, wishing I could’ve heard more about his transition from Notre Dame fandom to the Dawgs. Was it post-1988 with Notre Dame winning it all in the Fiesta Bowl? Those were dark days for Georgia football. A tough time to transition.

The mood in the ballroom sours. Warnock leads early.

A GOP volunteer says it’s easy for the Democrats to win when they cheat. Her tone has the sigh of a fan fuming about the refs. In Georgia, Governor Kemp, Carr, and Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger all refused Trump’s demands to monkey with the 2020 results. Trump endorsed each of their primary opponents. Each went down to defeat. Only Herschel wears Trump’s crown.

I ask the volunteer if she thinks everyone gets home before midnight. It’s 8:27 P.M. She shakes her head.

Democrats cheat. Stop the Steal. Children trafficked in furniture boxes.

Rosanne Boyland’s political enemy was Satan. Her rapid radicalization mirrored our slow boil at DCA, where we decoded current events with the Horses of the Apocalypse (White Horse, Red Horse, Black Horse, Pale Horse). But here, under the chandeliers, the Buckhead Young Republicans, Young Bucks, preside. Spiffy plaid blazers. Red cocktail dresses. Rosanne Boyland would struggle here.

No horses ride the wind of these speeches. No children packed into boxes. The target is not Satan but Nancy Pelosi. Her California home. Her indifference to crime. Her boutique ice cream. Biden’s sweet tooth for ice cream is called out. Big laughs. In the red notebook: a hastily drawn ice cream cone, circled by question marks.

Nostalgia buoys us mostly as it propels Walker entirely. We won’t apologize for America. We stand for the pledge. We protect our children (from thugs at the border, abortionists, reckless D.C. spending, drug dealers). Shards of Wallace. Shades of Nixon. The endless creak of Reagan’s rocking chair at the Neshoba County Fair. Some Palin dust. We nod before the lines land; we laugh before the joke.

This DJ, a diviner, reads the room: “Son, can you play me a memory? I’m not really sure how it goes.”

In the red notebook are questions I’ve wanted to ask Herschel my whole life. As a boy, I used to look for him at D’Lites, a short-lived Atlanta area based health-food restaurant, where Herschel was a franchisee. Much later, I passed him on the sidewalk coming out of a restaurant in Athens and was struck silent.

But Mallory is a ghost. And Mallory’s assistant Ashley says she’s sorry, she can’t help.

In the ballroom, Fox News cycles updates on DeSantis, JD Vance, and Walker.

In the red notebook, a date: May 5, 1991?

On May 5, 1991, Herschel Walker was hospitalized at Irving Community Hospital for carbon monoxide poisoning. His wife, Cindy, found him at 3:00 A.M. unconscious in his car (running) inside the garage.

Walker told reporters he was tired. Under stress. A long weekend of travel. His grandparents were ailing. Embroiled in a contract dispute with the Vikings over an insurance clause, the two sides were a million dollars apart. Reports suggested Walker was homesick for Dallas, too. Perhaps. The trade that made the Cowboys ’90s dynasty, with Walker at the center, left him in Minnesota.

Walker said he was listening to a favorite song on tape in the car and fell asleep.

When asked where he was going so late at night, he couldn’t say.

Reporter Jim Souhan of the Minneapolis Star Tribune looked at the pieces and called Walker. He said the story begged the question of suicide.

“It wasn’t anything like that,” Walker said. “It was just a really good tape.”

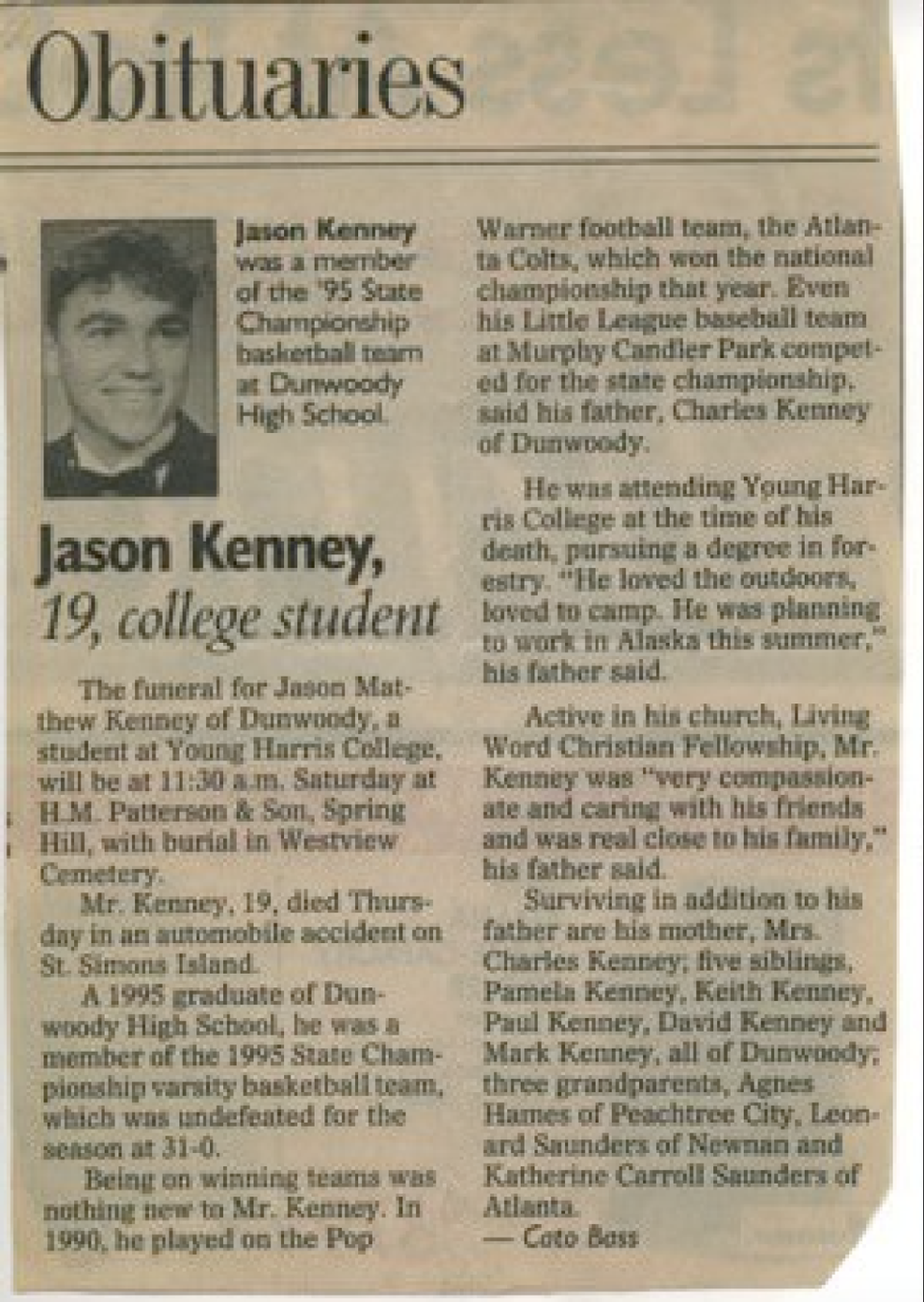

When I had my two distinct periods of suicidal ideation—following the death of my best friend (1996) and moving back to Atlanta (2016)—there was not a plan or even a conscious thought. A vision arrived in a flash, from somewhere else, wanting to pull me along.

In the ballroom, a woman spills red wine on her husband’s white-and-blue-checkered shirt. I catch a few strays. Merlot. She laughs and dabs his shirt. He mouths, “Sorry.”

The red notebook names: Bill Stanfill? Jake Scott?

Stanfill and Scott stalked the fields of the SEC for Georgia in the late ’60s. The Outland Trophy–winning Stanfill hounded Heisman winner Steve Spurrier to secure victory against Florida in ’66. Jake Scott played a wildman, All-SEC safety in ’68. Coach Vince Dooley called Scott the single greatest athlete he ever coached.

Stanfill and Scott were roommates at Georgia. Bill named a dog after Jake. And then a son. They were both Miami Dolphins, both multiple All-Pro selections, and both immortalized on the Perfect ’72 Super Bowl Champs. Both also shared the progressive disease of neurofibrillary atrophy, CTE, caused by repetitive head trauma. “I can deal with the pain,” Stanfill told his son in 2016. “But this losing your mind, I can’t handle that.”

After he retired, Stanfill spoke of football nearly breaking every bone in his body. He estimated he had more than 150 concussions. After he died in 2016, he was diagnosed with advanced stage CTE.

Jake Scott’s sister Rita is grateful dementia missed Jake, the free spirit, who was still able to travel between Hawaii and Colorado and Georgia until the end. He suffered ringing headaches, tremors, memory loss, imbalance, and black-out falls. He fell to his death in 2020. Scott was diagnosed with stage-four CTE.

In the VIP section, a cry and a gasp. A woman in a Sunday dress has fainted and collapsed against the VIP rope. On the floor, she’s out. Someone calls for a doctor and Mallory (!), who is not a doctor, appears and barks at the press to get back. Police arrive. Slowly, the woman regains consciousness. While it’s not the best timing, I look for Mallory, but she’s gone. Backstage? A police officer wheels the woman, head down, away.

In 2017, Dr. Ann McKee published a report in The Journal of the American Medical Association. In the study, 111 brain samples of former NFL players revealed 110 had CTE.

Herschel Walker, in discussing his own mental condition, says there are whole blocks of time and swaths of memories lost to him. Events—the 1982 Heisman Trophy Ceremony—he simply does not remember.

The symptoms of CTE include: memory loss, loss of concentration, personality alteration, mood swings, aggressive and often violent behavior, dementia, and suicidality.

According to a 2017 study at Stanford’s CamLab, the average Division I football player in a single game experiences blows to the head equivalent to sixty-two car crashes at thirty miles per hour. Every collision a crash.

On the same practice field of Stanfill and Scott, Herschel got his first handoff in 1980. Struck in the head by Eddie “Meat Cleaver” Weaver, Herschel went down, fumbled, and staggered up. Walker got the ball on the next play and was nailed a yard behind the line of scrimmage. Again, he fumbled.

A 2019 study from Boston University found that for every five years of a professional career, players doubled their risk of developing the worst cases of CTE. A career lasting 14.5 seasons was ten times as likely to develop CTE.

“I never been hit harder,” Walker told Memphis Press-Scimitar reporter George Lapides after that first practice: “I don’t know if I’ll get to play all that much this season. I’d just like to make a contribution.”

Herschel Walker contributed. His first season was his finest. His tolerance for pain legendary. When asked if it was hard to carry the ball so much, he smiled and said no, the ball wasn’t that heavy. The average career for a running back is less than three seasons. For fourteen professional seasons after UGA, Walker amassed 4,091 total carries, 668 catches, 232 kicks returned. Or: roughly 16,560 car wrecks. The cognitive toll can’t be measured. The memory fogs. A garage door closes. Probability is our only guide.

The ballroom erupts. Fox News has the update. All knotted up. Herschel has closed the gap. High fives! Don throws his fists in the air! We call out: “WOOF WOOOF WOOOF!”

At Georgia games, for kickoffs, we rumble GOOOOOOOOO and hold it until the kick and then: DAWGS! SIC ’EM! WOOF WOOF WOOF WOOF!

Mock it? That’s fine. Have you ever barked like a dog under a November moon with ninety thousand friends as Auburn, decked in all white, waits for the ball turning end over end, and the Dawgs come flying down the field in a blur of red tops and silver britches? You’d WOOF too. I’ve traded WOOFs at LaGuardia. I’ve WOOFED at Glacier National Park. Once at a bar in Santa Fe, New Mexico, when the Dawgs scored a strip sack TD, I went a-WOOFING as a pilgrim across the bar WOOFED too. Brother Dawg, he called. Brother Dawg, I called back.

This WOOF rises and rises and I can’t tell you the song as the WOOFING in the ballroom shook and shook.

Like Herschel, I was a chubby sixth grader. If it is the worst fate to befall youth, how blessed is life? At DeKalb Christian Academy, I was cut from the junior-high basketball team. Three sixth graders made it. That night, I realized there would be a seventh-grade tryout. A picture of Herschel catapulting himself into the end zone against Florida his sophomore year hung by my bed. In my head played the trumpet from Rocky. I knew the numbers. Herschel’s daily twenty-five hundred situps and fifteen hundred pushups. I could wake up and do thirty-four pushups and thirty-four situps. Herschel’s number. I could do the same after school. Before bed I could, too.

Out back, beside the stump, I no longer lazily daydreamed while shooting hoops. I put myself through drills. Timed layups. Defensive slides. Backyard sprints for every free throw missed. Pullups on the swing-set monkey bars. At night, sore, I stared at the picture of 34 soaring through space. The purity of the motion, the white jersey against the night sky, allowed the image to vibrate at the edges.

…from all the borders of itself, Rilke writes,

burst like a star: for here there is no place that does not see you.

You must change your life.

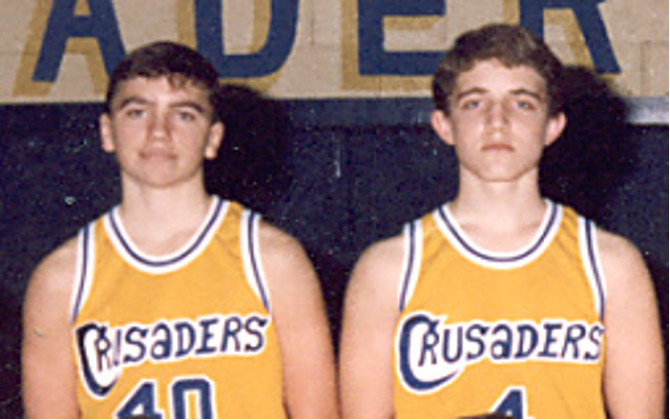

In the summer, I ran miles each morning as Herschel ran over a trail his father plowed. I skipped Six Flags and skipped rope instead. I ran sprints in the shade of the pine trees and birch trees and the pine stump took on a new hold. I kept an image of Jason, the best player in our class. Cocky Jason. Quiet Jason. Georgia Tech fan Jason. The sweat poured off me. I hit a growth spurt. I shed twenty pounds. I discovered muscle. For breakfast, fruit. A chalky protein drink for lunch. After dinner, if I got hungry, I chewed ice. I knew hunger. I knew cold. And when tryouts rolled back around, Jason Kenney would know me.

When he got winded, I got stronger. When he went for a rebound, my forearm found his chest. When he rose for a shot, my hand was in his face. There was no place he could go. The thrill was electric. To act, to be, to will, like Herschel, who read Cowboy Sam and watched hours of Bruce Lee and ran miles in the Georgia clay. The sensation of that summer in the backyard holds me still. I’d found a Yes, a No, a straight line, a goal.

9:10: Crunch time in the ballroom. In the red notebook: Dr. Jerry Mungadze?

Mungadze, who is not a medical doctor, has been essential in Walker’s life. He intervened the night Walker threatened to have a shootout with the police. He called the police on Walker when he punched a hole in his office wall. He also wrote the foreword to Breaking Free.

I called Dr. Jerry’s office to speak with him, and his polite receptionist said he was not giving interviews. When I mentioned the name of this magazine and told her of my interest in the mental-health aspect of Herschel’s story, since I had battled depression, she encouraged me to tell Herschel’s people that. I said I had. Really? She said. Really, I confirmed. I described the Mallory voice-mail situation. She sighed. Well, she said, and sighed again before wishing me luck.

But my luck might be out here in the ballroom, save a Hail Mary from Mallory and Team Herschel.

I feel as if I’ve known Herschel’s friend Dr. Jerry my whole life. He could’ve been a speaker at any Wednesday chapel service at DeKalb Christian Academy.

Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, Dr. Jerry launched his career as a Specialist in the Occult, Occultic Abuse, Spiritual Warfare, and later a Multiple Personality Disorder Expert. In the Dallas Metroplex in the ’80s and early ’90s, Satan was busy. Dr. Jerry was on the case. He addressed Chambers of Commerce, Baptist churches, and public school employees on signs of the satanic.

Keep an eye on children, he said. Ages five through nine: Is the child kicking or mutilating dolls? Is the child eating their own feces? Does the child seem isolated or withdrawn?

Folks in rural areas? Beware. “It’s much bigger in small towns. There’s less police enforcement, more open fields, empty barns.”

Dr. Jerry noted that cannibalism was on the rise in America, but it was hard to prove.

9:25: The screen flashes: WALKER 50 WARNOCK 47 The magic number. 50! The WOOFs are shorter, stronger. The room feels it now. The goal line. The DJ spins: “We Are the Champions.”

Some Young Bucks begin to chant: “Red revolution! Red revolution! Red revolution!”

This chant sags.

The Young Bucks pivot and go with: “Red wave! Red wave! Red wave!”

This sticks, rises. And hey! there we are on TV in the ballroom seeing ourselves on TV in the ballroom.

9:41: Village People: YMCA…and Herschel dips to 49.1…the WOOFs less woofy.

One of Dr. Jerry’s clients is “Real Exorcist” Bob Larson. You can laugh at his Skype exorcisms or claims to have defeated the Pale Horse’s Rider. Call him a fraud. Not untrue. But imagine you are at DeKalb Christian Academy and this man’s disembodied voice on a tape recorder fills the room, asking demons for their names.

“It’s easy to trick a child,” Dr. Jerry warned in 1990. “Children are vulnerable.”

Dr. Jerry guest-stars on Larson’s YouTube programs. This past summer, they discussed the difference between Alter Personalities and Demons. The difference, Dr. Jerry says, is tricky.

Herschel Walker once asked, “Am I crazy?” and Jerry had an answer. A series of answers. Answers that validated psychotic visions and mental illness as harbingers of spiritual truths, Dr. Jerry does more than harm.

9:51: …Walker jumps to…49.6, and both TVs show an image of Stacey Abrams losing the governor’s race to the incumbent Republican, and a chant of NAH-NAH-NAH, HEY-HEY…breaks out.

Herschel’s diagnosis comes down to crayons. Dr. Jerry showed gold-plated televangelist Benny Hinn his method in May 2013. He detects demonization in people’s brains through coloring sheets. A patient chooses a crayon and colors parts of the brain. From the crayoned areas, Dr. Jerry identifies the spirit/alter.

At the episode’s end, Hinn closes his eyes and reveals that out there in the TV audience a shoulder is healed. Diabetes? Healed. Fibromyalgia? Rebuked. “Eileen,” Hinn soothes, “God has just healed you.” Pancreatic cancer? Rebuked. A lady with a growth on the back of her right ear? She’s healed.

In a December 2011 profile by Steve Oney (UGA alum, Go Dawgs!), Dr. Jerry insists that Herschel is healed, the alters have been integrated, and the odds of Herschel exploding in anger? “Practically zero.”

Weeks later, Myka Dean called police to report that Walker had threatened to blow her head off.

Breaking Free is a ghostwritten book that’s haunted on every page. The trauma Herschel Walker endured is not of Satan. It cannot be crayoned. Trace it as far as you can to Johnson County Middle School.

We saw the blunt-force trauma Herschel Walker endured. Every Sunday. At the Meadowlands. Soldier Field. Veterans Stadium. The Big Blue Wrecking Crew. Monsters of the Midway. Gang Green. Fearsome they were. Gods they were not. They were men. Cut them. They too will bleed.

“Please,” former Chicago Bear safety Dave Duerson wrote in his final note to his family, “see that my brain is given to the NFL’s brain bank.”

“In the Air Tonight” rips across the room. Dr. Jerry is crossed out of the red notebook.

After my backyard revelation in seventh grade, I harnessed my work ethic into an absolutely average and unspectacular high school athletic career. When it ended, I found myself still running.

In my freshman year of college at Young Harris College, I reunited with my former teammate, Jason Kenney. As roommates, we stayed up too late and laughed too hard at DCA stories. Our two-year college sat in the foothills of the Appalachians. Some mornings, we ran along the Blue Ridge trails. Some nights we sipped moonshine from a mason jar chilling by twine in Corn Creek. We shot baskets and got rebounds and moved around the key like hands on a clock.

On March 21, 1996, during spring break, Jason died in a single-car drunk-driving accident in St. Simons, Georgia. He was driving. I was his passenger. They found our bodies in a traffic circle near two massive oaks with hanging Spanish moss. Jason severed his spine. His death immediate. I suffered a concussion, a broken foot, and road rash. In the hospital, I dreamed of running.

After Young Harris, I enrolled at the University of Georgia and kept running. I ran the track Herschel ran with his sister Veronica. I ran to Normaltown and the Naval Supply School under a long line of oaks. I ran past the library where on the sixth floor I had my view of the stadium from the stacks. I ran down Milledge to Dearing and past the Tree that Owns Itself. Each Wednesday morning, the grounds crew left Gate 10 on the south entrance to Sanford Stadium open. I ran the stadium stairs. Running countered atrophy. Running honored Jason. Running up the concrete aisles I counted to 34. Right foot, 34. Left foot, 34. Both feet, 34. Skip a step, 34. Skip a step with both feet, 34. The whole lower bowl of the stadium. In the summer, afterward, I’d walk over to Legion Pool and swim. 34 laps makes one mile.

10:15 Where’s 34? goes the red notebook. Restless is the room. I look up and my throat constricts.

Karl Rove bloviates on TV. They allow him on air? I see my students. The veterans I taught in my adjunct years who wrote essays of lost friends, limbs, lives. The dual-enrolled high schoolers on a military base who wrote about the dissolution of their parents’ marriages. My refugee students from Afghanistan and Iraq and Syria whose families were torn to the wind. Rove, war’s cheerleader. Rove, who was behind the Senate ads here in ’02 juxtaposing Vietnam vet and triple amputee Senator Max Cleland with Osama Bin Laden. America decides. Yes. Yes, we do. And the results are in. Depraved. We are a people most depraved.

The heart rate on my watch reads 108. I try Loving Kindness Meditation. Picture Karl Rove as a baby. Bald, fat, in a diaper. But he’s animated. He’s Boss Baby. No, I go with the basics. I follow my breath. Inhale, hold, exhale. Repeat. Go to ten. Start again. I stand there still.

Depraved? Sick? Suffering?

We are a nation concussed. The collision came on a Tuesday morning in September. One blow, then another. Secondary Impact Syndrome. The patient may become emotional.

“Bomb the hell out of them,” Georgia senator Zell Miller cries. “If there’s collateral damage, so be it.”

Pat Tillman watches fire and smoke billow over the skies of southern Iraq.

“This war,” Tillman says, “is so fucking illegal.”

A politician promises Hope and Change and pivots to drones.

The patient is confused about an assignment or position or is unsure of the game, score, or opponent.

A celebrity from reality TV, a caricature of ’80s excess, promises to build a wall.

A pandemic sweeps the land.

The patient may experience difficulty thinking, feeling slow, confusion, or forgetfulness.

Another old man is elected. He says the fever will break. The fever does not break.

The chaos at the empire’s edges comes home, the tip of the spear poisoned.

Ashli Babbitt, a fourteen-year Air Force veteran who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, uses her training in civil disturbance countermeasures to breach the Capitol. She, too, is a believer in Q. and seeks children in the furniture boxes. The shot is to her head. Blood runs from her mouth.

The patient may experience double vision.

In Afghanistan, the final shot in our longest war is a drone strike that kills a refugee aid worker and slaughters seven children, decapitating a two-year old.

So be it, the senator from Georgia said.

The patient can’t recall events prior.

David DePape, a Q. believer, shatters a glass door to Nancy Pelosi’s exclusive Pacific Heights home which she shares with her husband, Paul, a venture capitalist. DePape enters. He wants to kidnap Pelosi, break her kneecaps, and wheel her in front of Congress to answer for the satanic cabal.

He calls for Nancy. She is not home. He encounters Paul.

The weapon is a hammer.

The blow is to the head.

10:20: And here comes Herschel Walker. I am standing right in front by the podium. But wait. Doug Flutie! Multiple images are crossing—Orange Bowl, Sugar Bowl—as Flutie introduces Herschel. USFL teammates: Jersey Generals. Now Herschel comes into focus. No multiplicity here. Black suit. Dark red tie. There is only Herschel.

His accent, Georgian to the core, disarms you. I feel the old feeling and want to get him out of this place and far away from these people. But who are Herschel’s people? He hasn’t lived here in decades. Where are his brothers and sisters? Veronica, the track star? Herschel makes a Ricky Bobby reference. Big laughs.

He speaks for a minute and twelve seconds. His left eye is bloodshot, but he is comfortable. Trump’s shadow is up there too. Both hinted at political office long before they ran. Both mentioned being Democrat or Republican. Fame trumps coherence. Celebrity conquers all.

But Herschel sounds like the kid who wanted to be a Marine or FBI. Trump? Trump dances. Dances with a gleeful nihilism. Will he make fun of a disabled journalist? He will. Did he call Ted Cruz’s wife ugly? He did. Can he talk hair spray to coal miners? He can. A showman’s craft. A scent for cruelty.

Herschel is…earnest, simple…brain-damaged?

“We are here to win this election, are we not?” he says.

(We answer in the affirmative.)

“I’m gonna tell you this story. I’ve been talking about these two little boys."

“And one of these boys was always positive in life. No matter whatever happened to that kid, he was positive about it."

(“DO IT HERSCHEL!” the old boy next to me yells.)

“But this other little kid was always negative. No matter whatever was going on with this kid, he was negative about everything.

(Some low-key boos for this kid. We know him.)

“And the father didn’t know what was going on with these kids because they were twins, but they were so opposite."

(Plot twist: These boys are brothers? Not only brothers but twins!)

“So around Christmastime, he tried a little experiment. He put this negative kid in this room with nothing but brand-new toys. But he put this positive kid in a room with nothing but horse manure."

(Whoa, we say, and a few of us question the method of this perhaps-gaslighting dad.)

“And after an hour or so, he looked in on this negative little kid who was complaining and he was like, ‘I don’t want this, I want that. I don’t want this, I want this.'"

(We nod, not to each other, all eyes on Herschel.)

“And the father knew this kid would never amount to anything, because nothing ever makes him happy."

(Hard, but true.)

“But then he looks in on the kid in the room with the horse manure, who is in his room and he got a shovel. And he is shoveling that horse manure and he is laughing and singing and having a good time."

(Our hero. A lad of song and mirth!)

“First thing the father thinks is this kid has got to be crazy."

(Not necessarily.)

“But he says, ‘Son, what is going on? What is going on, little buddy?’

(Open-ended questions. Good. No-judgment zone.)

“You know, Dad. As much horse manure as there is in this room, there must be a pony at the bottom of it.”

(“Amen!” The bespectacled man to my left yells. We clap and cheer.)

Herschel smiles. It’s a winning smile. This plays. This horsey-tale. We want to believe. God, we do. I wanted to believe I’d talk to Herschel tonight, but this is as close as we’ll get. And despite the stench of this breakneck, quarter-billion-dollar race, we’d all take a pony at the end.

I opened the curtains to Room 15 at Wesley Woods Psychiatric Hospital at Emory University in September 2016 to the sight of pines. Insomnia, depression, suicidal ideation. Since moving back to Georgia that summer, I’d been unable to sleep. Visiting had never been a problem. But the reality of being here, putting down roots, spun me around. On that first morning in Room 15, and for each that followed, I dropped to my knees, put both hands on the ground, and did 34 pushups.

Georgia. The song was old but not so sweet. I had lived for years in New Mexico and Colorado, and the West was home. All that wide-open space. You saw what was coming from miles away. The sunlit running trails stretched over vast spreads of silence. In Atlanta, the world sped headlong—filled with too many cars going too fast, too slow, coming, going and never arriving.

I understood the ideation came from a lack of sleep. Brief thoughts of crashing my truck. Taking a broken piece of glass to my throat. I understood the chemistry in my brain was off. I did not run. I was not moving. The blue light of my phone allowed me to be neither here nor there. To my family, I was a ghost.

Like Herschel says of his D.I.D.—my case, compared with the folks at Wesley Woods, was mild. Humbled and fortunate, I went through therapists. I went through medications. I went through running shoes and yoga mats and new tires on my road bike. Good and better days passed until I stopped keeping track.

One day, I went for a walk with my daughter Grace, age three. We gathered stones and feathers, crabapples and acorns, and returned to the oak in front of our house. Grace opened her tiny fistfuls at the base of the tree and arranged her collection. Taking my hand, she said, “Now this is our tree.”

And I still can’t stand the traffic. And I check in with my breath. And the lady at Kroger who asked me last week if my soul was ready for eternity puts me in a certain place. But that place is home.

I’m later told by folks from the ballroom and bar that Mallory and Team Herschel believe this will be a “bad story.” Maybe. But the true story of Herschel Walker is not mine or Mallory’s to tell. While I won’t talk with Herschel, there are people Herschel can talk to.

Chris Borland listens to the stories. Since he retired from the NFL in 2015, citing concern of traumatic brain injury, he estimates he’s taken hundreds, maybe a thousand calls from former football players. NFL vets from the ’60s. Guys from Herschel’s era. Some who played college ball. Current high school kids.

On the morning we spoke, he had already taken two calls.

Something, the voices say, is happening to my brain.

Former Georgia defensive back and NFL player Tra Battle knows the feeling. Tra, like Borland, was an undersized defender who packed a punch. He played with the Chargers and the Cowboys (2007–09), primarily on special teams. Now, back in Georgia, the father of four works as a pastor.

“It’s coming,” Tra tells me.

I ask what it is.

“The loss of my mental acuity.”

He’s felt shades of it for some time. Paul Oliver was Tra’s teammate and roommate at UGA. On the night of Oliver’s death in 2013, Tra drove late at night to the Bear Creek Reservoir and looked out over the water. He called Georgia head coach Mark Richt, who ensured Tra got the help he needed.

Like Jake Scott, Tra played fearless, even concussed. Like Scott, Tra would black out and collapse, randomly, at home. Now Tra drives to pick up his kids for volleyball practice or a soccer game and he asks himself where he is going and retraces the steps of how he got there.

The post-concussive world dulls. You are not yourself. But on most days, he feels good. He wants to “build gray matter through synaptic pruning.” Despite the shadows, Tra has clarity.

“I want to take ownership. I have it now. I will use it to the best of my ability.”

Tra puts listens to different perspectives and thinks critically. Whether it is in the study of scripture or a recent disagreement with his wife, Luisa, where she suggested they stop—not in front of the kids. Tra checked in. Took a breath. Paused. He asked her if they could try again. Maybe even show the kids how two loving adults can disagree, reconcile. So they did.

Today, Tra shares his story of depression and mental health with groups large and small throughout the state. He’s moved by the response and later when someone writes or whispers: That is my story too.

Now Tra considers it “our story.”

About Herschel Walker, Tra says amongst UGA lettermen, there is a triad structure. those who love him; those who are indifferent; those who loathe him. Tra is indifferent but mentions players struck by how Walker presents on the trail.

At a lettermen gathering this past year, he says the vibe was straight out of a high school cafeteria. Guys passing out campaign stickers. Guys complaining about the stickers. The triad structure.

“I just want to know his motivation. Why? Why now? Why this?”

That is Harry Carson’s question for Herschel, too.

The Hall of Fame linebacker and former New York Giant squared up against Herschel in Walker’s NFL debut. Monday Night Football. September 8, 1986. Cowboy Stadium. Herschel dazzled, two TDs, including his signature over-the-top score and a late ten-yard charge to secure a Cowboy victory.

“I’m really down,” Carson told reporters postgame. “There’s nothing to be happy about.”

Beyond the outcome of a single game, Carson grew aware of his own possible brain damage in 1981. Depression and suicidality struck. One day, Carson drove over the Tappan Zee Bridge in New York and resisted the urge to plunge into the Hudson. He noted a slower memory and delayed speech post-retirement and wondered, “Am I going crazy?”

A diagnosis of post-concussion syndrome followed.

Carson ties Herschel’s motivation back to Donald Trump. “The guy who used to be president wants a rubber stamp in the Senate. And I think he enjoys the potential symbolism of one Black man defeating another Black man.”

Carson grew up in a rural South Carolina town similar to Herschel’s home., , The longtime resident of Franklin Lakes, New Jersey has been approached previously to run in New Jersey’s Fifth Congressional District. “I declined then and would refuse now because I would not put my family through that.”

He never loved football, he tells me; he loved his teammates. Carson says he continues to have “clandestine conversations” with men whose brains have likely been damaged.

“What price do you put on a brain?” he asks. “There’s not a price I would put on my grandson’s brain.”

Strangers approach Carson in line at Starbucks. They shake his hand in Home Depot. No longer do they belabor tales of Super Bowl glory and the Gatorade baths he gave Coach Bill Parcells. They thank him for speaking out on brain trauma and depression.

“There are so many people,” Carson says, “who are hurting.”

When the wounded call, Chris Borland picks up.

“You have to really empathize with their situation, treat them with love, respect, and care,” Borland tells me. “They may have varying degrees of baseline intellectual capacity, brain injury, and mental illness.”

He is not a licensed medical professional, but Borland now has years of experience as a player advocate and can connect players with resources. While there have been gains in treatment since his own retirement, Borland points out how gambling and fantasy football further distance fans from the humanity of players.

What does Borland make of the political rise of Herschel Walker?

“Walker is unique because he’s jockeying for a position that would have tremendous power and shape the lives of many Americans. It’s fair to try and better understand his capacity before getting into mental illness or brain injury. Is he a smart, effective, good decision maker?”

Borland has doubts, even absent potential brain trauma, about Walker’s fitness for the position.

“Then you add this associative disorder and likely significant brain injury over decades and I think those questions are fair to ask when someone enters the public arena and wants a position of power. It’s delicate, but can we have someone who’s unwell and probably lacks the ability to begin with to be in a position of power?”

Borland sees the jokes about Walker’s cognition and finds them crass and dismissive.

The pace and brevity and the emotional charge of our public discourse, he says, doesn’t allow for nuance or a lot of space for these conversations.

“What’s the quote?” Borland asks. “Justice and truth are too subtle of concepts for our blunt tools to touch accurately.”

Until justice or truth arrives, here’s a local offering.

The ritual of bedtime at the Battle house in Jefferson has stayed the same through the years.

Goodnight, Tra says to each child.

Goodnight, they follow.

I love you, he says.

I love you, they follow.

See you in the morning, he says.

See you in the morning, they follow.

Some nights, the Battle kids flip the script. As Tra approaches in socked feet down the hall, his oldest son calls out first. Tra follows. His daughter too lets him know. Those three words. Tra repeats and smiles. The words of the youngest boys travel through the dark. Tra says their names from a place beyond blood, beyond bone. For as the sun will rise, so too will the child who is loved.

Exiting the Omni ballroom, the star of this show sends us out with the Stones: You can’t always get what you want...yes, but who needs three more weeks of this? Runoff. In the lobby, it’s already tomorrow. 12:19 A.M. I spot Don Knobler. “How we doing, Don?” I ask. He sighs and tells me we are tired. We laugh and I wish him safe travels back to Dallas. He wishes me luck with the story.

Outside the hotel, the wind whips and the acre of plastic grass doesn’t move. Service workers heave bags of trash into a dumpster. The valet service rotates out a fleet of Teslas, a Lambo, a Porsche SUV.

Walking uphill to my car, I think of Jake Barnes, at the end of The Sun Also Rises. He’s been concussed at the fiesta, hit in the head. Blurry, he feels like he once did when coming back from an out-of-town football game.

Hemingway’s nine documented concussions ranged from the everyday to the geopolitical. While he played a lumbering, unspectacular guard in high school and boxed his whole life, he became our poet of the concussive with the Austrian mortar shell on the Italian front. That blast yielded A Farewell to Arms. Car crashes (Wyoming, London, Cuba, Chicago) followed. A skylight in France. A German shell in World War II, a motorcycle overturned. Two plane crashes, two concussions in Africa in 1954. To escape the fiery second crash, he rammed his concussed head into the jammed door. Cerebrospinal fluid leaked from his ears.

Toward the end of his life, Hemingway could not write. Irritable, forgetful, abusive, paranoid, brandishing guns, he withered. On a Sunday morning, up in Idaho, he ended the story. His grave in Ketchum sits under a big blue spruce; a cone from its branches rests on my desk under soft lamplight.

Herschel, like Hemingway, wrote bad poetry in high school. From Glory! Glory! Georgia's 1980 Championship Season: The Inside Story by Loran Smith we find:

I wish they could see

The real person in me

Someday I reckon they will know

I’m not only here for the show

The real Herschel animates from his brain. We mistake the thighs and shoulders and hands for essence. But like an oak in full canopy, what’s most essential is hidden. The root system, like dendrites, pulse with life, allow for life, are life itself. Dendron, from the Greek, meaning: tree. A damaged brain struggles to signal to itself. To others. Yet a tree, even without a brain, can assist another tree with nutrients, care.

Two Young Bucks carry a huge HERSCHEL sign overhead toward the parking deck. The wind catches the souvenir and spins the boys around. “Dude!” one yells. “DUDE!” his companion calls. Baby Bucks. A silver F-150 Raptor stops and the window lowers. Young Bucks and Baby Bucks. No memory here of My God a freshman or Herschel Over-the-Top. They missed the miracle.

I wish like hell Herschel had been stopped tonight by his lukewarm opponent, common sense, or himself. He doesn’t need this. In high school, he spoke of the Marine Corps. At UGA, he spoke of going back to Wrightsville to pump gas. In the NFL, he moonlighted as a bobsledder and a ballerina. Turn away, Herschel. Run.

Just like that Sunday morning back in Athens, a week after the Heisman. December 12, 1982. While jogging, Herschel came upon a crowd at East Campus Road and Milledge Avenue. A wreck. Two cars, one overturned. A sixty-seven-year-old woman was trapped inside the upended vehicle. Smoke poured from the hood. The door, stuck. No budge. Herschel stepped through the crowd, ripped off the door, pulled the woman to safety, and then jogged off.

“Off into the sunset,” one witness said, even though it was still morning.

He could do that now. Goodbye Trump. So long Young Bucks and Botoxed VIPs. Herschel could hit the old trails, running. The Oconee forest in Athens. The sliver of beach along Jekyll. The rolling hills of Blue Ridge. Go. Go make amends with his kids. Forget this show.

A nice thought. But tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, on stage after stage, throughout the state, Herschel Walker will tell us a tale. We’ll nod. Raise our hands. And in our opulence or boredom or rage, we’ll reach for the bluntest of 5G tools and post. Go Dawgs. God Bless. Woof…woof.

There is no red America, a senatorial candidate once mistakenly intoned, no blue America. Of red and blue, there can be no doubt. But the hour gets late. And the clock is ticking. You can hear it. Even here.

The powerstroke diesel pulls out of the lot and heads for the crowded four-way intersection below. The dual exhaust mufflers hum with the power of five hundred horses.

You Might Also Like