Girls are affected by stereotypes by age 6, new study shows

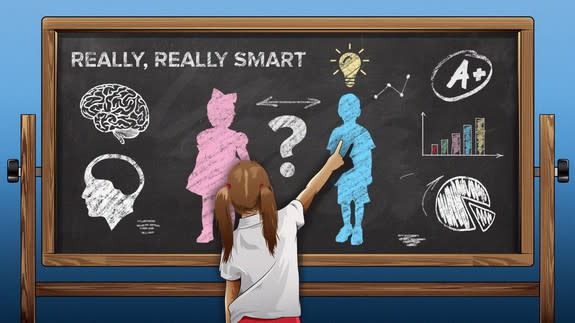

Who is "really, really smart?" Boys or girls?

A new study found that young U.S. girls are less likely than boys to believe their own gender is the most brilliant.

While all 5-year-olds tended to believe that members of their own gender were geniuses, by age 6 that preference had diminished for girls — a difference the researchers attributed to the influence of gender stereotypes.

SEE ALSO: 7 strategies for raising confident girls in the Trump era

"We found it surprising, and also very heartbreaking, that even kids at such a young age have learned these stereotypes," said Lin Bian, the study's co-author and a doctoral candidate at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Image: Vladimir Trefilov/Sputnik via AP

"It's possible that in the long run, the stereotypes will push young women away from the jobs that are perceived as requiring brilliance, like being a scientist or an engineer," she told Mashable.

A growing field

The study, published Thursday in the journal Science, builds on a growing body of research that suggests gender stereotypes can shape children's interest and career ambitions at a young age.

A global study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found that girls "lack self-confidence" in their ability to solve math and science problems and thus score worse than they would otherwise, which discourages them from pursuing science, engineering, technology and mathematics (STEM) fields.

A 2016 study suggested a "masculine culture" in computer science and engineering makes girls feel like they don't belong.

Image: AP Photo/The Christian Science Monitor, Ann Hermes

Thursday's research looks not at specific skills but at the broader concept of high-level intellectual abilities. In short, can girls be geniuses, too?

Sapna Cheryan, a psychology professor at the University of Washington who was not involved in the study, said the results were "super important" because they're among the first to show us how young children — not adults or high-schoolers — respond to gender stereotypes.

But she said the findings are just as revealing for young boys as for girls.

"It's not that girls are underestimating their own gender — it's that boys are overestimating themselves," she told Mashable. Cheryan was the lead author of last year's masculine culture study.

"What we want as a society is for people to say boys and girls are equal," she added.

Stereotyping starts early

Andrei Cimpian, a co-author of Thursday's study, said his earlier research with adults showed that the fields people associate with requiring a high level of smarts also tend to be overwhelmingly represented by men.

"Across the board, the more that people in a field believe you need to be brilliant, the fewer women you see in the field," Cimpian, an associate professor of psychology at New York University, told Mashable.

This same idea burrows itself into our brains as children, the study suggests.

Researchers worked with 400 children ages 5, 6 and 7 in a series of four experiments for the new study. (Not every child participated in every experiment for the study.)

In the first experiment, the psychologists wanted to see whether children associate being "really, really smart" with men more than with women.

To answer that question, a researcher told each child an elaborate story about a person who was brilliant and quick to solve problems, without hinting at all at the person's gender. Next, the children looked at a series of pictures of men and women and were asked to guess who from the line-up was the character in the story.

During a series of similar questions, researchers kept track of how often children chose members of their own gender as being brilliant.

Among 5-year-olds, boys picked boys a majority of the time, while girls picked girls.

"This is the heyday of the 'cooties' stage," Cimpian said. "It's consistent with what we know about in-group biases in this young age group."

But among 6- and 7-year-olds, a divide emerged. Girls were significantly less likely to rate women as super smart than boys were to pick members of their own gender.

The age groups were similarly split in a second prompt. Researchers asked kids to pick from activities described as either suited for brilliant kids, or kids who try really hard.

Five-year-old boys and girls both showed interest in the smart-kid activities. But by age 6, girls expressed more interest in the games for hard workers, while boys kept on with the "brilliant" games.

Why is this happening?

Researchers said it's not entirely clear how these stereotypes form. Certainly marketing towards children — lab sets are for boys, dollhouses are for girls — plays a role.

And history books are filled with the achievements of white men who, generally speaking, did not face the same systemic discrimination that kept women and people of color out of classrooms and laboratories.

Cimpian and Bian said they are planning a larger, longer-term study to explore how these stereotypes form and stick, and how we can correct them.

In the meantime, they suggested a few ways that parents and teachers of young children could work to dispel the biased idea that men are inherently more prone to brilliance than women.

Bian noted that previous research has shown that girls respond better to what psychologists call a "growth mindset" — the idea that studying, learning and making an effort are the key ingredients for success, not a stroke of genetic luck.

"We should recommend the importance of hard work, as opposed to brilliance," she said.

Image: Joseph Rodriguez /News & Record via AP

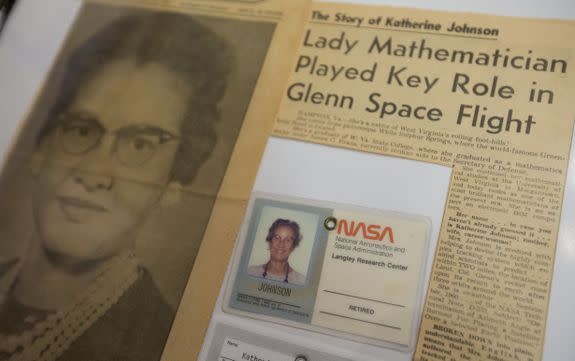

Sharing and touting the achievements of women can also help counter the stereotypes that genius is reserved for men. Cimpian cited the book and movie Hidden Figures, about the women scientists who helped NASA astronauts get to space for the first time, as a prime example.

Cheryan, the UW psychologist, said including young boys in such efforts is critical.

"There's a societal message that if there's a gender gap, it's the girls we need to fix," she said. "We have to be careful with that message, because it just reinforces the similar hierarchy that the boys are always doing the right thing. In reality, there's probably things that could happen on both sides."