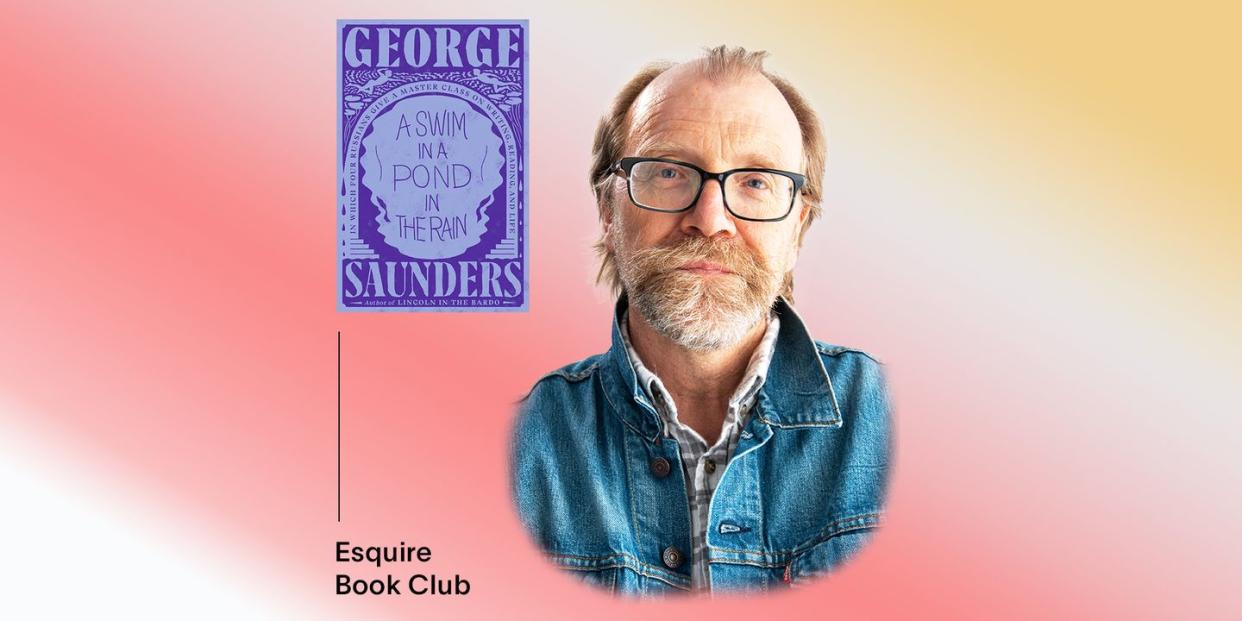

How George Saunders Is Making Sense of the World Right Now

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"The part of the mind that reads a story is also the part that reads the world," George Saunders writes in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. It's perhaps the truest distillation of Saunders' visionary life and work, encapsulating the characteristic generosity and humanity of his artistic outlook. Saunders—the Booker Prize-winning author of numerous works of fiction, including Lincoln in the Bardo and Tenth of December—has spent over two decades teaching creative writing in Syracuse University’s MFA program, where his most beloved class explores the 19th-century Russian short story in translation. In A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, Saunders has distilled decades of coursework into a lively and profound master class, exploring the mechanics of fiction through seven memorable stories by Chekhov, Tolstoy, Turgenev, and Gogol. In these warm, sublimely specific essays, Saunders’ astounding powers of analysis come into full view, as does his gift for linking art with life. By becoming better readers, Saunders argues, we can become better citizens of the world.

On the day after a violent mob stormed the U.S. Capitol Building, Saunders Zoomed with Esquire from his home in upstate New York. What followed was a far-ranging discussion about how to write, how to read, and why both matter, even—and perhaps especially—during such a tumultuous time in human history.

Esquire: George, I've got to tell you—I loved this book so much. It's going to live on that special shelf of my bookshelf reserved for books that get me unstuck when I feel stuck in my writing.

George Saunders: I'm so glad to hear that. I'm at the early stage where not that many people have read the book, so it's always interesting to hear how people react to it. I’ve never written a book like this before. For me, as you get older in this world, it's interesting how you're always fighting your habits. Now, with each book, I ask myself, "Can I find some weird corner to get into and some new thing to try?" I'm going to be starting my career as a ballet dancer soon. That's my next thing.

ESQ: You've been teaching this class for over two decades, but at what point did you decide that the wisdom of the class should become a book?

GS: These days, I’m actually teaching less. I got a reduced load a couple years ago. When that happened, there was a moment where I realized I might not teach the class again. That thought made me sad, and it made me think fondly on all those beautiful mornings in different classrooms around the campus. I had the feeling of, "If I don't write it down now, I'll forget it with each passing year." At this stage of life, you look back at all the stuff you've done with an almost scientific clarity. You say, "This part of my life was stupid. I shouldn't have done that.” Or, “This part of my life was a blessing. I'm so glad that happened." Teaching fell into that latter category. It's been such a privilege to have such brilliant young minds to interact with all these years. They've taught me so much. Writing the book was a way of taking a breath and saying, "Let's get back in touch with teaching, and let's get back in touch with the short story form by going back to the woodshed.”

This is an interesting book, because when you write fiction, you have a little bit of a conquistador attitude in your mind, saying, "You're going to love my stories." With this one, it's more like I'm trying to throw a little party. I’m saying, “Let's get together, and all of our better natures will gather around these Russians, and we'll have a little fun." I feel somehow like a party host for these four friends that I really love.

ESQ: What were your early experiences with the Russian greats? How did you come to their work, and how did it resonate with you in those first encounters?

GS: When I was in college, I was an engineering student. I wasn't doing any literature reading at all, except for fun. One summer, my dad got a job in New Mexico, running a gas station for drill rigs out in the middle of nowhere—a place called Rosebud, New Mexico. I was out there for the summer helping him, and there was nobody my age around. So I did a lot of reading; I remember reading Dostoevsky at that point and thinking, "Wow, this guy is really a philosopher," which, at that age, was very appealing to me—somebody who would give me all the answers to my little male head. I also saw Doctor Zhivago during that time; I found it so romantic and big-spirited. It was those corny things that added up to an interest in the Russians. Then, years later, I heard Tobias Wolff, my teacher, read Chekhov. That's where it really clicked for me. I wanted to somehow be part of that lineage. I’m a working class person who was trained as an engineer, so I always assumed that the point of someone telling you a story was to help you live better. Those were the kind of stories we got in the neighborhood: "Hey, don't go up by that house. That guy's crazy. He'll kill you." I always understood stories to be primarily didactic—to give you some kind of life lesson. The Russians came right in through that doorway, for me.

ESQ: What does the Russian short story offer that’s unique to itself—that perhaps the prototypical American short story doesn’t offer?

GS: I saw this demonstrated when I tried to teach a parallel course in the American short story. It wasn't as good a class; somehow those stories just didn't spark for me the way the Russian stories do. I always say that the Russians come directly at what I'd consider to be the big questions of life. So do Americans, but there’s something to the simplicity of the Russian approach. You get the sense that they weren't afraid someone might think they weren't edgy enough. “The Death of Ivan Ilych,” that great Tolstoy story, is just about a guy dying. It's so bold. It's as simple as, "You're going to die. I'm going to die. Let's look at it." As a working class kid, I read writers like Kahlil Gibran and Robert Pirsig; Pirsig wrote a book called Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which was very philosophical in a light way. I always assumed that's what literature was about, and the Russians seemed to agree with that.

ESQ: There's a great matter-of-factness to the Russians that I just don't find in American writing. It's not that they have all the mysteries of life figured out, but they’re so convincing and assured, even in their questioning.

GS: At least they’re asking the right questions. They're asking the questions that you're going to be asking someday when the wolf comes through the door. I love that about them. American writers sometimes have to dress those questions up in something else. I come back to the Russians over and over again. I taught these stories for twenty years, but then to be able to come back to them… I basically didn't read anything but these seven stories for a year and a half. It was amazing to see how they just kept opening up. Every reading, you'd notice something you didn't see before.

ESQ: In the introduction, you write that you’re seeking to help your students achieve “their iconic space—the place from which they write stories only they could write, using what makes them uniquely themselves.” What was your own process of identifying and achieving your iconic space?

GS: Early on, I told myself, "Anything that's working class or funny, strike it out, because that's not high class. That’s not literature." Of course, because that's so much of who I was as a person, omitting that led to some really stilted, false writing. There came a point where I was so tired of not feeling like myself on the page. There comes a frustration when you know you're a unique human being who knows some things about the world, but somehow the writing isn't showing that. That's the most maddening thing. That’s the gateway to style, really—to say, "I'm going to accept all those things about me that I normally deny." The way to do that is to see when the prose lights up. If you're writing in a certain mode and the prose is boring, that means you're keeping yourself out of it somehow, whereas when the prose lights up and even you can't help but read your own prose, that means you're letting yourself in.

All my life, I've always tried to be funny. My first girlfriend broke up with me, and she said, "I just can't stand that you're always joking." Then I made a joke, of course. At some point, you have to say, "Look, I am what I am." We can't do much about our essential nature, but we can accept it, and then we can somehow make it a quality of our writing. It was also about admitting that money was an issue in my life. I thought, "I'm reading a lot of stories about trout fishing in Spain. But I'm not doing that. I'm working every day, and the work that I'm doing is affecting my energy and my good nature." That should be literature. There should be some room in literature for that.

ESQ: I completely agree. I often feel like the literature of work is so undervalued. It's a huge dimension of our lives that sometimes feels absent from the page.

GS: In America, it's so dominant. The working world expects so much of your soul. That’s where our lives are taking place, actually, in the pressure cooker that work makes on our grace.

ESQ: Elsewhere in the book, you write about your decision to stop imitating other writers, and to embrace what made “Saunders Mountain” unique to “Hemingway Mountain.” For many writers, especially young writers, the path to discovering their own mountain can be long and winding. What advice do you have about discovering that ineffable thing about your own work? Are there exercises people can use?

GS: I'll tell you one that we do. It's very simple, and it seems kind of stupid. I'll bring in five opening paragraphs from short stories that I find in any literary magazine. I take the authors' names off, and I have the class read those five paragraphs. I'll say, "I'm going to leave the room. When I come back in, have them ranked from best to worst, favorite to least favorite." I go out. I don't say anything about the criterion. I just say, "Rank them." Because they're writers, they have no problem preferring. Then I say, "Read me your order," and they do. Of course, no one ever agrees, which is the best. But the important part is when you start saying to them, "I want you to recreate your reading experience. When did you start to love or hate this piece of writing? Go down to the phrase level.” That's actually how it works. If you pick up a book in a bookstore, a book that's gotten a lot of great reviews, written by someone who's one year younger than you, god forbid—you read it, and instantly you're opining about it. That's a really valuable thing for a young writer: what do you really love about prose, and what do you hate about it? It’s maybe the one part of our lives where we get to be so opinionated without being obnoxious.

That’s a pretty good exercise to make ourselves aware that we have that little needle in our heads. We have crazily refined micro-opinions about things. That, I think, is the hidden superpower. The pathway to the uniqueness we're talking about is turning down your inner nice guy who’s always trying to like everything. Turn that down, and when you read a bit of prose, watch that little needle flicker. That's where a person's uniqueness lies. If you then make a career of radically honoring those little preferences with every sentence, pretty soon the whole book has your stamp on it, which is ultimately what we're looking for. When I pick up your book, I want you to be there. I want you specifically to be there. And the way you get yourself in there is by those 10,000 micro-choices.

ESQ: Something that strikes me about this book is its sense of altruism and generosity. For so many people, a formal training in creative writing is inaccessible, yet you’re sharing that wisdom for the price of a hardcover. Was that part of your ambition here, to reach people who are not in the ivory tower receiving a creative writing education?

GS: Yes. This whole process of reading and writing, and that holy process of two people talking about a story together... I think it makes everyone's life better. Everyone should be able to do that. Somehow, in my lifetime, storytelling has gotten downgraded. Science and technology are understood to be great because they get you a job, but this very essential human thing of asking, "What are we doing here, and how should I behave?"—that has somehow become considered a bit of an indulgence. And it isn't. In the last ten or fifteen years, there's been this assumption on the part of aspiring writers that to be a writer, you must have an MFA, and that if you have an MFA, you'll automatically be a writer. Both of those assumptions are false. An MFA is nice, and for certain people at certain times in their trajectory, it's helpful. But I've seen other people ruined by it. I think we want to be a little bit playful and say, "Well, if someone gives you a bunch of money to come write for three years, that's good. But if you have to go $80,000 into debt to get very little attention for your work, that's not so good." Even though my whole life is MFA stuff, I'm a big fan of debunking the primacy of the MFA degree. You don't need it. But if you’re a writer, you need to think deeply about stories in the way that I try to model in the book—not necessarily in my exact way, though.

ESQ: This book is so much about the building blocks of fiction. "Rules” is perhaps too strong a word for those building blocks, but I wonder: what are the rules of fiction that you find tiresome, or that you enjoy breaking?

GS: In my scientific background, we learned the distinction between rules and laws. Rules say: you must do this. A law says: things tend to happen in this way. The law of gravity is that gravity exists. We don't get to negotiate about that. There are things that, when you pick up a book, you expect to happen, which then create a series of laws. Specificity is one of them; cause and effect is another. What I object to is the idea that there are universal principles in writing. We know there aren't. A good MFA program is about one specific person, me, who has a very prejudicial idea of writing, meeting another person, you, who has an equally prejudicial sense of it. Then I have to find a way to tap that person lightly and help a little. Whenever I hear somebody say with confidence, "You have to show, don't tell," or, "Write what you know”... that’s all true to the extent it is until it isn't.

Part of my teaching practice is to be almost insanely New Age about that part of it. At the beginning of the semester, I say, "I'm going to act like I really know what I'm talking about. But believe me, every day when I go to write, I have to remind myself that I don't, because this is a particular story. It's not every story. It's this particular one." I say to this incredibly talented group of people, "Look, we're all in the same mess together, which is that we want to be writers, but it's hard. Nobody can give you a general answer." There's a lot that's wrong with the MFA model and the workshop model. What I try to do is keep undercutting it so that we're aware of the limits of the experiment.

ESQ: A lot of writers and creative types have felt paralyzed by the pandemic, and have reported that they’re struggling to create. How has the pandemic affected your creativity and your ability to write fiction?

GS: Honestly, I feel bad saying this, but I'm being mad productive. I'm having a great time. I finished this Russian book, and I finished four stories. I used to travel a lot for writing, but now I'm not, so that's really been good. Times like these, that are so sad and so charged; they remind me that fiction is supposed to somehow be a response to that. It's a moral, ethical tool. When I'm out here in the middle of nowhere and I'm sad about what happened yesterday, or about George Floyd, or about the way the election played out, I feel it percolating in my head. What it's telling me is, "This world matters." The only way I have to deal with those feelings is through my art form. At this advanced age of 62, I find that my artistic mechanism is pretty well-equipped to take that on and make it flow through. In a personal way, I haven't seen my parents in a year. We have a daughter we haven't seen in about eight months; she’s out in L.A. That's sad. But in terms of the writing, it's taken a lot of confusion away. I'm no longer traveling. I'm just at home, where it's me and my writing. So it's been okay.

I could imagine that this time might be hard for some people, because there's this huge thing happening in the world. The question is: do you write directly about that thing? For me, the answer is no. I can't. I don't think I'll have a pandemic story. But how do we take that huge thing happening and use it in such a way that fiction doesn't seem irrelevant? I remember, after 9/11, thinking, "What in the world could we write right now?" These Russians remind us that a really good story is eternal. That Tolstoy story in the book, “Master and Man,” is about power dynamics. You could easily make that story a commentary about racism, because whatever it is that's actually behind racism, which is power, is totally opened up in that story. I've been trying to think that whatever the pandemic is "teaching" me will come out eventually. It'll come out in some form. It won't be a story about face masks, but somehow it'll be there.

ESQ: What do you expect that the emerging fiction of this time will look like? Do you think this moment will change fiction, whether it be in its forms or in the actual bread and butter of the stories?

GS: It will because it always does. That's one of the real blessings of teaching—seeing that talent never ends. Every generation is equally talented. It’s a standard old person's stance to believe that it diminishes, but teaching teaches you that it doesn't, though it does reform itself. People have different things that are bothering them, and form is the way we accommodate that. There's a burning question for this generation. They find a new form to express it. This will definitely affect fiction; we don’t and can’t know how.

But here's what I hope. I hope that it will burn some of the self-indulgence out of our fiction. We're such lucky people. We have so much wealth and so much comfort relative to other times and places. Sometimes I think that can get into our fiction and make it self-obsessed. I think this whole time is a reminder that the wolf is also coming for us; that no human being can escape sickness, death, and sorrow. The pandemic is a force that makes us say, "I am subject to all those things. Fiction is there to help us, or at least to take into account all these scary things.” Maybe the prayer would be that it makes our fiction more intense. Then, in turn, fiction might again become a more central part of our culture—one that regular people turn to in times of need because it helps them.

ESQ: I’m curious what it's like to be a young person studying creative writing during these tumultuous times. What are your students writing about? What's on their minds, and what are their impressions of the way of the world, these days?

GS: I had a great group this year. I had a six-person workshop that we did on Zoom. It was really unusual because every single story they submitted had a lot of merit. There was nothing half-baked or unformed. In some ways, their stories are about the eternal big questions. I think I'm noticing a little more angst about the future, or a sense of, "Why are we living this way? Why am I, a young person, feeling so adrift? What is it about our culture that got us into this mess?" I’m seeing evidence of what I just hoped for: their stories are more urgent. The gaze in the story isn't coming back to them; it's going outward at the world. Maybe what I'm talking about is already happening.

It's so refreshing for an older person to see, well, people like you, who love reading and are bright and not beaten down by the world, and who are courageous in their artistic aspirations. To be put in touch with that every semester and in every interview is so nice. It allows me to say, “The world is not degrading. It's actually beautiful." Sometimes the observer degrades; a person gets cynical as they get older, but teaching is a way to keep your freshness of mind, because you walk into a class of six brilliant people. They happen to be 28 years old, but in a certain way, once you start talking or once you start reading these Russian stories, everybody's the same age, which is timeless.

ESQ: In this time marked by a pandemic, political turmoil, and this nasty strain of anti-intellectualism, what does fiction matter? Why is it still important to how we live?

GS: I think it's because it's not something apart from the way we live. When any person walks into a grocery store, they're basically writing a novel. They see a woman with two little kids, and they make a story up about her, even if they don't realize it. It's called projection. A novel or a short story is not something foreign to us. We do it all the time. We generalize without very much information, and we make assumptions about the world, about, "This is how we stay alive." If we're good at it, we not only stay alive, but we stay alive compassionately, and we become better at being patient with other people. By imagining their circumstances, we make a more spacious universe. That's a skill you have to practice.

As we're seeing now, if we don't practice it—if we practice the opposite of it, which I’d argue we practice every time we're on social media about politics—then what we're doing is short-circuiting the process of generous projection. We're projecting hateful caricatures of each other. Obviously that has an effect on our neurology. It makes us more anxious, more nervous, more accusatory, quicker to act. It would be great if everybody would read all the Russians, though I don't think that's going to happen in America. But I think those of us who love fiction can be a little more vocal in our defense of it. We can recognize that storytelling is something we’ve have been doing forever to make community. We've been doing that since we were cave people. And, as you correctly said, there's something about the anti-intellectual climate that I think is related to our materialist agenda and our pro-corporate mind, which says, stupidly, that only that which equals immediate value is valuable. We become very dopey linear thinkers, and we make the mistake of thinking that this apparatus in our heads is capable of understanding the universe. It's actually not. Your brain is just a survival tool.

Reading and writing have always been there to help us be more expansive and less deluded about reality. We think we're at the center of the world; that we're permanent and dominant. It's not true. Reading breaks down that delusion a little bit, but it's incremental. It's just like having good friends or having good food or being in love or having a nice place to live. It just helps. It doesn't solve the problem forever, but it might be part of the mix of things that makes this life worth living.

ESQ: This makes me think of something you’ve said in the past; you called good prose “empathy training wheels.”

GS: Here's another thing. I have to tell you a story. My wife had to have a medical procedure a couple years ago, right after Trump won. We went into the hospital, and there was another couple in this waiting area for the families of people who were having surgery. This couple came in. Now, this is me projecting, but I'm pretty sure they were strong Trump supporters. The four of us stood there a little bit nervously because it was a big day. My mind was going, "You idiots! How could you vote for that guy?” Then the husband went off, and my wife went off. Then the other wife and I joined the bigger waiting room. The hours went by. At one point, a doctor came out and stooped down and talked to this woman; you could see that the news was not good. At that moment, just because we'd spent that little time in that waiting room, my heart went out to her, and I went over. I said, "What's going on?" She said, "The cancer is back. This is it."

Now, that moment where I felt drawn to her was every bit as real as the moment where I felt aversion to her. That's a short story. That energy is short-story energy, which is, “I thought I knew her, and I thought I knew what I thought of her. But just by abiding there a little bit, I found out that I was capable of a little bit more.” That's essentially what reading is. It's not a complete antidote, but I think we all could all stand a little more of it. Sometimes you have to act. Sometimes you have to arrest people who go into the Capitol. That's a no-brainer. But even in that process, if you have some fellow feeling for them, you're going to do a better job.

You Might Also Like