George Carlin’s Bittersweet Melody

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

My father’s first serious girlfriend after he and my mother broke-up was a dream for my twin sister, younger brother, and me. Kaye lived just down the block from my grandparents on the Upper West Side, a genial, welcoming woman, and possessor of that enviable 1983 daily double: a VHS machine and cable TV (we didn’t get either at my mom’s house for at least three more years). My sister Sam and I turned twelve the summer Dad lived with Kaye, a cushy, temporary stop for him. Their relationship didn’t survive the year, yet was full of pleasure for us kids: Eddie Murphy’s Delirious (HBO); Young Frankenstein (VHS); and a Marilyn Monroe documentary (VHS) that launched Sam’s abiding fascination with the actress.

It’s also where we first encountered George Carlin. The one-two punch of seeing his HBO special, Carlin at Carnegie (filmed in ’82, aired in ’83), and listening to his 1972 Grammy-winning album, FM & AM, arrived at a crucial moment. Staying up late to hear cursing was more than a titillating novelty. It was passage into a secret society. As the co-eldest, I didn’t have the benefit of an older sibling or cousin or friend to introduce me to cool bands, movies, magazines, attitudes, and ideas. With one step into an adult world I didn’t understand, hungry to develop my bullshit detector, Carlin provided a reassuring, avuncular presence. He was the bridge between Bill Cosby and Richard Pryor (never mind Lenny Bruce and Lord Buckley)—the known and the forbidden.

My father, born a few months after Carlin and raised fifty blocks north, stuck to booze and never got into drugs. But he liked the comedian and I watched closely when he listened to the album with us, studying what made him laugh hardest. Divided into two-parts, FM & AM was Carlin’s breakout solo record. “He de-transformed into who he actually was,” says Patton Oswalt in George Carlin’s American Dream, the stellar new two-part HBO documentary directed by Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio. (Part One begins streaming tonight, May 20.) “It’s that great moment that every comedian wants to get to … where the person you are off-stage is the person who you are onstage.”

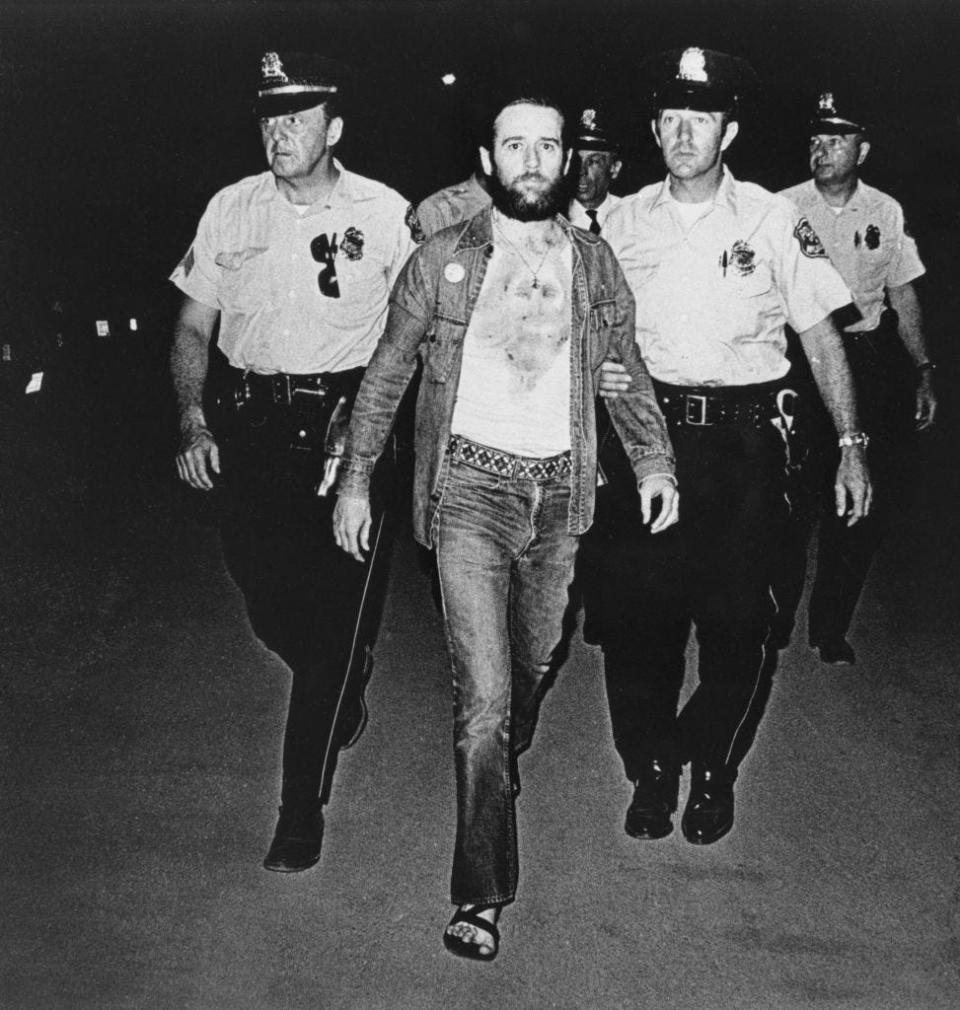

“He was a road comic ’til the day he died,” says his daughter, Kelly Carlin, elsewhere in the production. The many stops in Carlin’s fifty-plus-year career, including origins as class clown at a progressive Catholic school, stints as a radio DJ, coffee house comic, mainstream TV comedian, and longtime stand-up virtuoso, unfold in this candid, laudatory, and forceful documentary. It’s a sweeping tour of a comedian’s life and times. As Carlin said over and over again, he wasn’t on anyone’s side—left or right. Group of all kinds gave him the willies. But George Carlin’s American Dream is a corrective to any notion that he belongs to the right. It's also especially effective at detailing Carlin’s obscenity case in the early ’70s, and does a nice job of admiring its subject without turning him into a martyr—this isn’t Lenny.

The first side of FM & AM begins with a routine about the word “shit” and details Carlin’s fall from grace as a successful middle-class comedian. (“Bad breath, yeah ... ‘Anyone can have bad breath, Marge, but you could knock a buzzard off a shitwagon.’”) Tired of selling out for older Republican audiences, he grows his hair long and flourishes as a counter-culture comic performing in coffee houses and at colleges. His routines get longer and looser. This transformation, the call to be true to yourself—a lesson we’d learned on Sesame Street—rang true, even though by the time I heard FM & AM the counterculture was long over. That didn’t matter. Carlin’s unhurried delivery—droll, friendly, bust-out-loud-funny, and almost always melodic—seeped deep into my pores (to this day I imitate Carlin’s throwaway noises and sound effects). The second side, AM, didn’t have the allure of cursing, but was equally as funny and satirical just lighter and more revved-up, a greatest hits of Carlin’s work from the ’60s.

On FM & AM, Carlin questions conventional wisdom and mistrusts authority. He examines obscenity and language and drug culture—not just recreational drugs but mainstream drugs such as alcohol and caffeine. He probes about drug companies and how athletes use drugs. Also about sex, particularly sex in advertising. It didn’t matter that most of the cigarette brands he lampooned in 1971 no longer existed, the ironies held true. Here was someone who made me question everything from how a word sounds to how the government and big industry function. Carlin broke the news to us—the world is incorrigibly corrupt, stupid, and prone to evil—with indignation and compassion. We listened to the record over and over—as well as the ensuing masterpieces, Class Clown (1972) and Occupation: Foole (1973), which we memorized. He was indispensably good company.

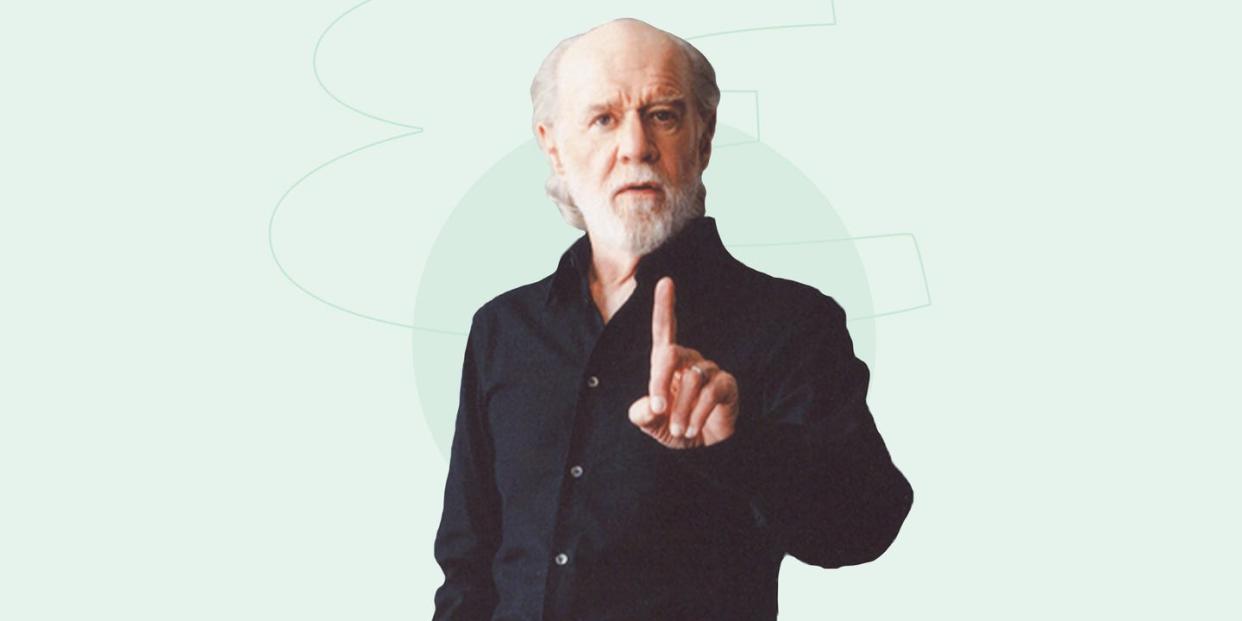

We also loved Carlin at Carnegie concert even though it was a departure from Carlin’s hippy-dippy persona. Hair cropped short, beard too, he looked leaner, energized—and cranky. The “Hey, whadda say?” mellowness replaced by a more agitated—sometimes really fucking pissed off—countenance. Carlin’s anger was funny and understandable. It was the Reagan era, after all: the bad guys had won. Mellow didn’t cut it anymore. Irritation and outrage were the order of the day, even in his observational, non-political routines.

As we come to appreciate in George Carlin’s American Dream, here was an entertainer unafraid to tact with the times. A decade later, for instance, during the height of the first Iraq war, Carlin’s 1992 special, Jammin’ in New York, is a blunt, severe tour de force. Carlin, now slightly hunched, uncoils a storm of social commentary and jokes in a stripped-down style suited to the post-Andrew Dice Clay/Howard Stern/Bill Hicks comedy moment.

What remained constant for Carlin lay in the meticulousness of his routines, or as Jerry Seinfeld marvels in the new HBO work, “getting every word in the right spot.” Carlin, after all, is a writer who performed his material. The filmmakers make smart use of a trove of archival treasures, including home tape recordings (some melancholy, some batshit crazy yet still hilarious), video footage, and journal entries. Just as in Apatow’s absorbing 2018 documentary The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling, we get a vivid evocation of comic’s life and creative process. It never veers too inside baseball, though with Carlin the temptation is palpable; listen to this incredible 2002 interview with Larry Wilde to see how introspective, articulate, and smart Carlin was about his writing and performing.

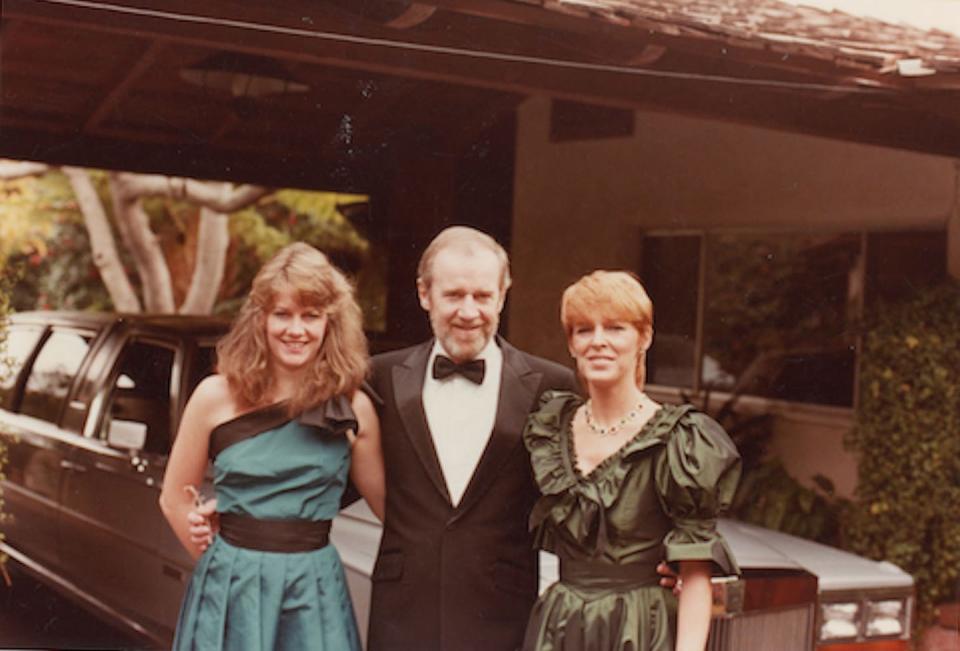

Carlin’s tenderness is revealed in love letters to his first wife, Belinda—their story is heartbreaking and poignant—and singing lullabies to his daughter, Kelly. They are especially touching considering the steady unrest in Carlin’s private life. Abandoned by an abusive father, who died when Carlin was young, raised by an overbearing, self-absorbed stage mother, Carlin struggled with addiction for years. He admitted to living life from the neck up, forever disconnected from his emotions, darkness never far from the surface. He once sent his older brother a small manilla envelope, on which he wrote: “For those days when everything has got you down.” Inside was a photograph of their father’s gravestone. Kelly Carlin, in fact, often seemed like the only adult in the room. And in her interviews, she is a forgiving though steeled-eyed observer, a realist—the heart and soul of the documentary.

In his later years, Carlin’s material was unsparing and bleak, his sense of betrayal and disappointment in the world complete (Carlin would have loved Franco-Belgian comic book artist Andre Franquin’s late-career strip, Idees Noire). Only a true believer would care so much. I watched Carlin from afar in his final decades, appreciated his evolution, stood in awe of his drive and discipline, and never begrudged his disappointment in humanity or his deep pessimism. If he didn’t make me laugh as much that was okay—didn’t mean he was any less funny. I’d grown up; didn’t need him in the same way I did as a kid. And when I do, he’s forever there waiting to replenish my faith in curiosity, observation, love, and what’s really fucking funny.

You Might Also Like