Garth Brooks and the Art of Arena-Sized Humility

In the summer of 1997, Garth Brooks played a free concert in Central Park, and because free was right in my mid-20s entertainment budget, I rounded up some friends and went. None of us was a country fan in general, or into Brooks in particular, but it was a hot August night, so we staked out some space in the North Meadow, just to see what was up. Roughly 980,000 other people decided to meet us there. It was a night I have never forgotten.

Last night, we watched Brooks receive the Kennedy Center Honors, alongside new honorees Debbie Allen, Dick Van Dyke, Joan Baez, and Midori. The Kennedy Center Honors are given to performing artists for their lifetime contributions to American culture, and for his music, his record sales, the way he modernized country and pushed it into the mainstream, Garth Brooks deserves his. But he's entered my personal pantheon for something else, something even more American.

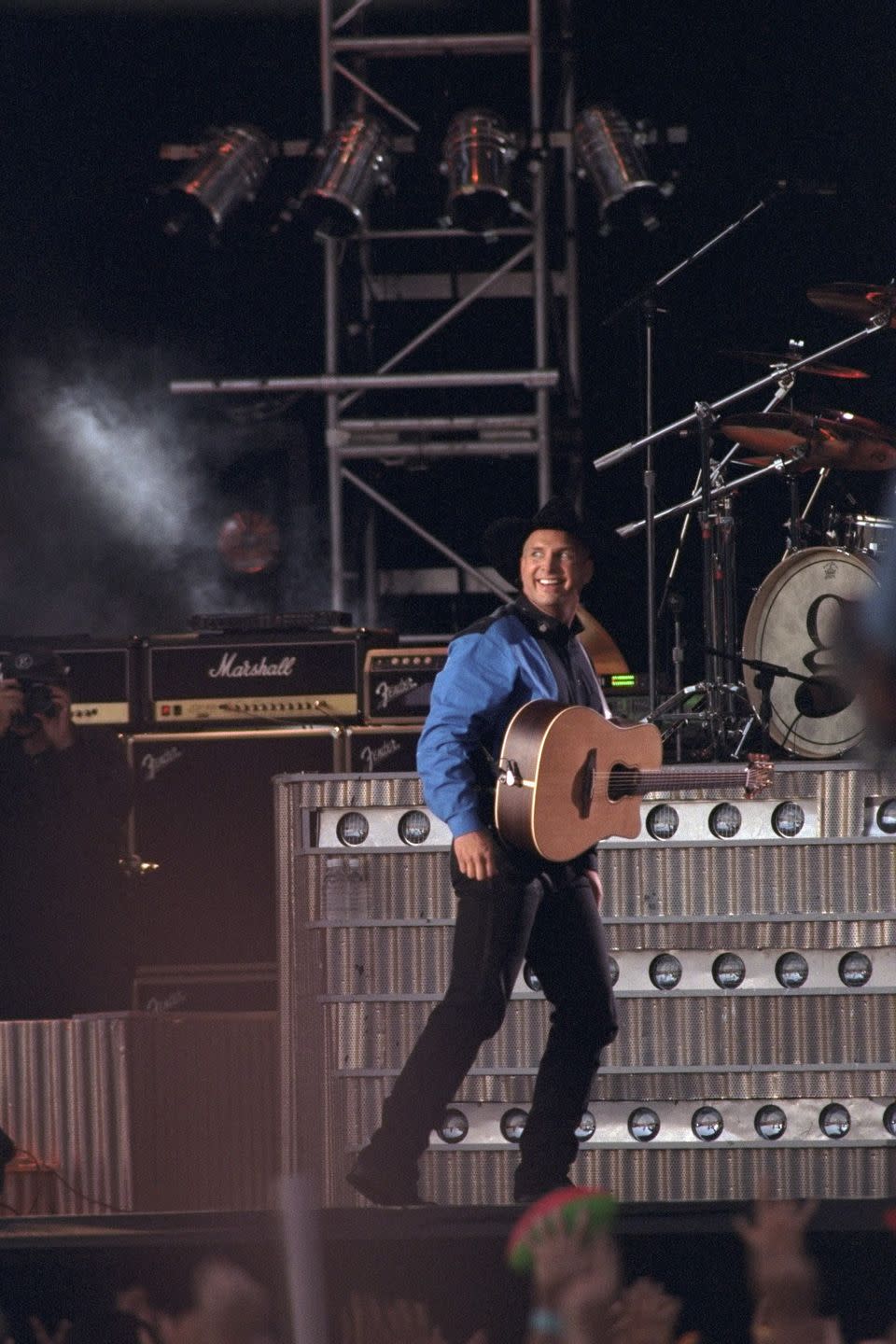

What I remember from that night in Central Park isn’t the music, not really. There were guest appearances by Billy Joel, which made sense given the location, and Don McLean, which made sense given that “American Pie” feels like the correct name for the genre Garth Brooks works within. By 1997, the songs he was selling on that stage were mass-market rock with a handful of country signifiers: a slide guitar here, a Stetson and a color-block button-down there. Country in exactly the way Def Leppard was metal.

The way jazz people tell you—before you walk away from them—that it’s the notes musicians don’t play that matter, that night in Central Park I learned the real magic of Garth Brooks is what happens between the songs. Each one of his songs was amped up to arena level, each one ended on a POW! on which he could strike a pose: a fist in the air, his back to the crowd. And so he did, pretty much every time. When the crowd roared, which we did every time, he turned around slowly and looked out at us in a pantomime of disbelief.

Now, again, the crowd was very large, and he is famously from a town that is very li’l, and I’m sure that’s a surreal experience. But this was deeper. This was, “You’re clapping your hands? For me?” It was not the humility that some artists across all genres work hard to project, not the award-show winnerface even Taylor Swift had to leave behind. It was him insisting, in the middle of this once-in-a-lifetime spectacle, that he was just a regular guy, which made the crowd react more, which made the spectacle bigger. Over and over, all night long, in a cleanly-mixed feedback loop. Arena-sized modesty.

It was very, very corny, and I loved it more each time he did it. By the end of the show, I swear I believed him.

For all the ways country does not look or sound anything like it did 10 or 60 years ago, the rules around it haven’t really changed:

• You must be affable 100 percent of the time. If you need proof, look back to 2017 when Taylor Swift– past country by then but forged in its traditions– made a concept album about sometimes not being in a great mood.

• You have to include references to drinking, and if that or any gerund is in the song title, the law requires replacin’ that final G with an apostrophe. A recent exception that proves the rule is a hit by Dustin Lynch and MacKenzie Porter called “Thinking ‘Bout You.” Do you see how they still managed to make it a technically perfect country song title?

• You should try to actually sing the word “country” as often as you can. Like America, country music seems like it will fall apart if it doesn’t tell itself about itself every five minutes.

• Most importantly, if you are praised in any way, be it by applause or awards, you must behave as though it is the first time such a thing has ever happened to you. It does not matter if you are the all-time best-selling solo albums artist in the United States, as Garth Brooks is; if an audience claps for you, you have to act like the whole thing is some big misunderstanding.

The audience has to, on some level, be aware of the artifice. One half-second of thought will remind you that your favorite country artist did this very thing the night before and will again the night after, and all the nights after that. Of course Garth Brooks knew you were going to clap and hoot at the end of the song, just like of course David Blaine can’t levitate. But as I learned that night in Central Park, there’s no joy in looking for the wires. Isn’t it fun just to believe? Doesn’t life on Earth require a conscious act of faith?

By and large, the rest of the world does not do country music, so they do not force their artists to behave this way. A thing we’ve been doing to get us through lockdown is projecting old concerts on a screen in our backyard and inviting friends over to watch, a necessary stopgap measure until live music comes back and an even necessary-er distraction in an uncertain time. Recently, we put on Robbie Williams’ 2003 set at the Knebworth Festival, a show with a smaller but still incomprehensibly large crowd of 100,000.

Williams acts as though he knows he’s supposed to be there. He behaves both like he deserves that crowd, and like he’d be enjoying himself just as much alone. Of course, his swagger and flash are just as much of a put-on as Garth’s humility, the flip side of the same counterfeit coin. (They are also, as Robbie has since acknowledged, the byproduct of lots of cocaine.) But America doesn’t allow its pop stars to act this way. If you’re self-important, it had better be toward a larger purpose than yourself. You better be out there saving the world. It’s why we’ll accept the sanctimony of a Chris Martin or a Bono, yet we are the only country on Earth where Robbie Williams wasn’t massive. It’s why he lives here now, in fact: because he’s actually plagued by self-doubt and would rather be in the one place he can be certain he’ll be left alone.

Brooks does this sort of calculated modesty in a very special way, in a manner that suggests he is extremely humble and an absolute goddamn lunatic. Please treat yourself to the first video he posted to Facebook some years back. If you have never seen it, it is a wild ride.

Brooks maintains his common-man demeanor while acting exactly like an alien in a skin suit. He keeps his strange, grandiose humility— a hotel room? Me?— at the end of his five-year Las Vegas residency and the start of his three-year world tour. He gives you wholesome root-beer dad energy, even as he delivers an “I like that,” which qualifies as assault in most of the United States. He plays the part of a regular guy, but also one who has just invented social media five minutes ago in November 2014.

In last night's broadcast of the Kennedy Center Honors, Brooks watched as his songs were performed by Kelly Clarkson, Jimmie Brown, James Taylor, and Gladys Knight. And as you would expect, he was overwhelmed. But so were all the night's other honorees, and so have they all been, forever; Behold Carole King watching Aretha Franklin plunk her purse down on a piano and slay "Natural Woman." This is the country's highest honor for an artist, the celebration of a lifetime of work, and the only context in which Garth Brooks reaction shots kind of just feel normal. (He did, however, give an interview to CBS This Morning on Friday in which he told Gayle King that his wife Trisha Yearwood "smells like nothin's impossible," so you'll want to sit with that for a moment.)

When Brooks is good, there are few who are better. He has earned his place in the American cultural canon. “The Dance” can reduce a grownup to tears, “We Shall Be Free” was legitimately controversial in 1992 for simply acknowledging homophobia and racism, and future Americans should have to know about Chris Gaines. Aw heck, he deserves the Kennedy Center Honors solely for 1990’s “Friends In Low Places” and its significance to the then-emerging practice of karaoke. He’s iconic.

It’s not a mistake that Garth Brooks’ music is hugely popular. But he deserves recognition for decades of walking this tightrope, for being the most popular artist in a genre that does not allow its artists to act like they know they're popular, for being a superstar who still has to talk to you like he's your Little League coach. The Kennedy Center Honors celebrate great artists and their lifetime contribution to American culture, and– I say this with awe and respect– Garth Brooks is a master of the greatest and most American of arts: pure, satisfying bullshit.

You Might Also Like