GameStop Showed Wall Street Wins Even When It Loses

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s a tale as old as time in business: One group of aggressive interlopers targets another group, and they fight it out. One comes out ahead; the other gets run over. Historically, however, one of the groups isn’t a loose amalgamation of strangers on the internet, nor is it led into battle in part by a pied piper who calls himself Roaring Kitty and streams investment hot takes from his basement.

“We’re being shown the tendies by Mr. Market,” said Roaring Kitty, whose real name is Keith Gill, on YouTube while celebrating GameStop, the video game retailer, reaching a market cap of $2 billion in mid-January. “Tendies” is internet-speak for market winnings worth savoring, like chicken tenders, which Gill just happened to have on hand to land his joke. He pulled a tender into the frame, staring almost earnestly into the camera, brandished the morsel, and asked his anonymous audience, “Can you dip it in champagne?”

The young troublemaker, who bears an uncanny resemblance to Cousin Greg on Succession, was one of the supporting players in a saga that took Wall Street by storm at the start of 2021. He was among the horde of traders, many of whom organized on the WallStreetBets forum of the social media platform Reddit, who helped drive a spectacular—albeit fleeting—rise in the price of so-called meme stocks, companies like the now infamous GameStop, BlackBerry, and others considered by most investors to be on the decline.

In the process they cost some big names big dollars, like New York Mets owner Steve Cohen and his hedge fund, Point72; Cohen’s former acolyte Gabe Plotkin, of the hedge fund Melvin Capital; and Daniel Sundheim, whose D1 Capital Partners was one of the top performers of 2020. They had been short-selling GameStop stock, and they were down billions of dollars by the end of January, victims of a short squeeze that forced them to participate in their own unraveling, largely at the hands of people in tax brackets far below theirs.

Wall Street’s potentates are used to going after one another—or being insurrectionists themselves. The savvier ones are students of history, and they remember that market manias, speculative bubbles, and short squeezes have been around for centuries. But every now and then even captains of industry get taken by surprise, and lately they’ve been kept on their toes by a barrage of novel financial vehicles and the arriviste investors driving up their value.

Between cryptocurrencies, special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), and non-fungible tokens (NFTs)—Christie’s sold a piece of digital art for $69.3 million in March—crazy money has entered an unprecedented phase. This has unnerved many veteran corporate raiders and ancien régime high rollers, some of whom recall earlier periods of upheaval but can’t recognize the current cohort of underground instigators, who do most of their plotting online. One thing is undeniable: The Davids have figured out how to rig parts of the game in their favor, and the Goliaths have to learn some of the new rules.

“These guys thought that retail was stupid, and they were happy to be on the other side of retail, and, actually, they got smoked,” says Benn Eifert, chief investment officer of QVR Advisors, a boutique hedge fund.

HISTORY’S FIRST BUBBLE

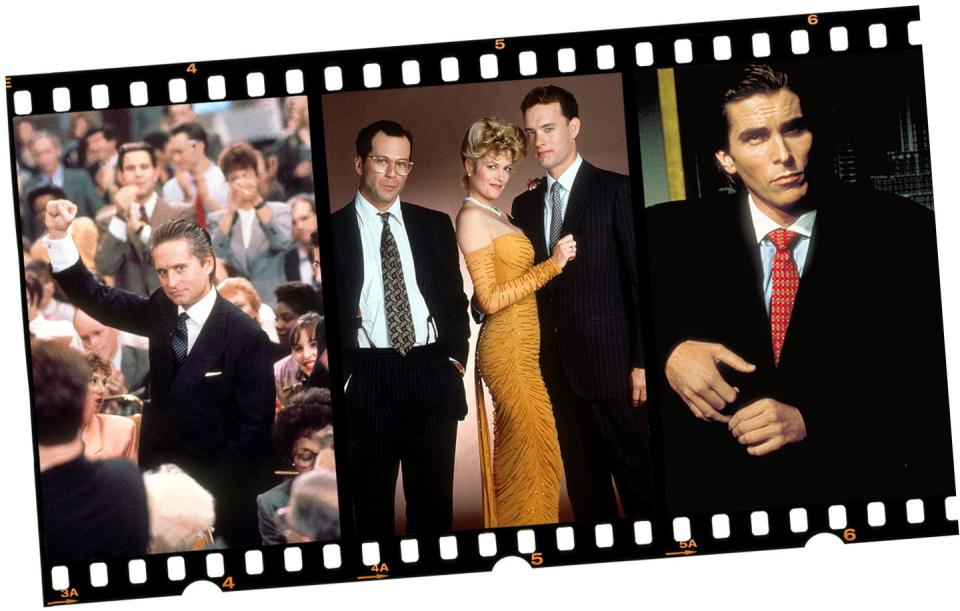

During the 17th century, the Dutch economy—one of the most complex in the world at the time—was so consumed with tulip fever that the Flemish artist Jan Brueghel the Younger portrayed traders as avaricious monkeys in a famous satiric painting. That was one of the first overheated markets, but it wouldn’t be the last. Centuries later would come the Roaring ’20s, the 1980s Wall Street boom, the dot-com bubble of the 1990s, and the financial crash of the late aughts.

There have always been those who were able to take advantage of such moments of turmoil. The ’80s saw the rise of corporate sharks such as Carl Icahn and T. Boone Pickens and the proliferation of hostile takeovers and displays of ruthless capitalism, such as Henry Kravis’s epic battle for control of RJR Nabisco. Hedge fund manager Michael Burry foresaw the subprime mortgage crisis before it happened and profited handsomely. (Incidentally, he invested in and made money on the GameStop craze as well.) Indeed, much of what’s happening today is reminiscent of the 1990s: Reddit is the new chat board, free trading is the new cheap trading, and investment ideas are equally risky—even reckless. “Everything old is new again,” says Barry Ritholtz, CIO of Ritholtz Wealth Management and a well-known Wall Street pundit.

Recent circumstances have exacerbated matters. Robinhood, the seven-year-old startup whose 13 million day traders turbocharged the GameStop frenzy, isn’t just free, it’s like Candy Crush: It makes investing feel like gaming. Locked down in their homes due to the pandemic, bored people were playing stocks, and thanks to stimulus checks some had more money to do it with. Analysts estimate that billions of dollars from stimulus checks (“stimmies,” as the online crowd calls them) flowed into the market. Technology made it easy for all this money to move fast, and traders were hungry for ideas, the kind that weren’t being shared at two-martini lunches at the Capital Grille or happy hour at the 21 Club, but instead by strangers gathering critical mass on Reddit, Twitter, and TikTok.

Investors have always sought information, says Divya Narendra, the founder and CEO of SumZero, a closed social network for investors. What’s notable is where many of them are now looking. “They all value the wisdom of crowds,” Narendra says, “so the question then becomes, which crowd do you value, or do you just value any crowd?”

Wall Street paid attention to this growing crop of small-time day traders but considered their activities little more than a bit of noise from the wildlings beyond the Wall. That may still be true, but in the words of one insider at a major hedge fund, the “obnoxious” noise has proven worth listening to a bit more closely.

On the surface it’s hard to take a forum like WallStreetBets seriously. Its users call themselves “degenerates” and use crude and often homophobic terms. They post strings of rocket emojis signaling that they want to send a stock “to the moon” and talk about “YOLO-ing” into positions when they go all in. They are mostly young and male, and they’re at war with the so-called suits: the Wall Street Brahmins they believe have been shilling them bad investment products for years and manipulating the markets against them. And even though not all of them know what they’re doing, it appears enough of them may.

“Pretty smart people were behind the short squeeze, and they may not wear a suit and tie to work every day and have Goldman Sachs on their résumés, but they were no market idiots,” says David Bahnsen, managing partner and CIO of the Bahnsen Group, a private wealth management firm.

In one video Roaring Kitty laid out part of his investment thesis for GameStop: “Many think it’s a foolish investment. But everyone’s wrong. It’s like the big short again, or more like the big short squeeze this time, right?”

That video was posted back in August 2020. Gill is no dummy; the thirtysomething father, who posts as DeepFuckingValue on Reddit, was a registered broker and used to work for a Boston-based insurance company.

LET THEM EAT “TENDIES”

When a hedge fund shorts a stock, it’s betting that the price will go down. It borrows shares of the stock, sells those shares, and, if all goes well, buys them back when the price plummets. Then it returns them and pockets the difference. If the price goes up, cue the red siren emoji. At some point the hedge fund has to buy the shares back to return them, and doing that drives the price up more—hence the squeeze. The potential losses are essentially infinite.

“What we saw with GameStop is simply what every short seller has to deal with,” says Fahmi Quadir, chief investment officer at Safkhet Capital, a short-only fund. “Positions go against you. Most of the time the market is going up; most securities are always going up. Why this became such a widely discussed phenomenon has to do with the wrong people being on the other side of the trade.” In other words, the suits would prefer to keep the right to be ruthless to themselves.

GameStop’s stock closed the first trading day of 2021 at $17.25 per share. During the third week of January, at its peak, the company traded as high as $483, its price vacillating so dramatically that the New York Stock Exchange had to pause trading on it multiple times on two consecutive days. Redditors were egged on by Tesla CEO Elon Musk, Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, and Social Capital CEO Chamath Palihapitiya. There were rich-guy agitators, but there were also plenty of rich guys agitated.

One fund shorting GameStop, Plotkin’s Melvin Capital, found its investments down by more than 50 percent at the end of January, according to the Wall Street Journal. Cohen’s Point72 and Kenneth Griffin’s hedge fund, Citadel, stepped in to provide $2.75 billion in emergency funds to Melvin amid the chaos. After getting trolled online over the bailout, including by some Mets fans, Cohen announced he was taking a break from Twitter. A couple of days after changing his Twitter bio to #bitcoin, Musk said he would take a hiatus from the platform too. Citron Research, run by famous short-seller Andrew Left, said it would stop publishing research reports about its short corporate targets, bringing to an end a practice it has undertaken for two decades. “The environment is aggressive and angry right now,” Left says, noting that some traders targeted him and his family. “What I don’t like about it is the meanness of it all. If this is the new way, let them have it.”

REVENGE OF THE REDDITORS

The funds that were betting big parts of their portfolios against GameStop were out on a limb—a limb many on Wall Street acknowledge, privately and publicly, they weren’t wise to be on. They were used to being a one-man mob going after companies, and they missed the smaller guys coming after them.

“These people were hoisted on their own petard,” Ritholtz says. “The Redditors basically said, ‘Oh, so you think you can go on TV and push a narrative and a meme and drive this down? Well, let us show you how the meme game is played.’ ”

Though retail traders aren’t a monolith, it’s fair to say that the GameStop boom wasn’t based on the stock’s fundamentals. It was spun from a more visceral place, a collision of emotions and egos, technology and culture, nostalgia and anger, all magnified in a place prone to hyperbole: the internet. Many of the names investors favored are relics of the recent past, like the retailer Express and AMC theaters. For the little guys it felt good to try to stick it to the honchos actively rooting against the mall store they remember going to as teenagers, or the movie theater under siege during the pandemic. The Reddit crowd favors overblown responses that can prove nihilistic at times.

On January 31 the moderators of WallStreetBets posted a “State of the Union” message, since removed, that marveled at what had transpired. “Could you imagine two weeks ago a crusade was brewing, that several million traders would soon band together to fire one big shot across the bow of some the most powerful entities in the world. How could you have?” they wrote.

The emotions go both ways. Some on Wall Street bristle at the idea of this pesky, chaotic group of anonymous hooligans pushing stocks around. “There’s nothing very serious people dislike more than the unwashed masses getting rich, and doing it for lesser intellectual reasons,” one trader says.

APRES LE MEME STOCK, LE DELUGE

This story is not a linear one. The New York–based hedge fund Senvest Management, which bought into GameStop last September, made $700 million off the January brouhaha. The hedge fund Citadel reportedly lost a smidgen of its $2 billion investment in Melvin Capital in January, but Citadel Securities, which processes trades for Robinhood, profited nicely off the day-trading boom. The two Citadels are managed separately, but they are majority-owned by Griffin, who is worth more than $20 billion. Even when Wall Street loses, it wins.

Meanwhile, many Redditors who piled into GameStop—especially when it was trading high—lost money. “The foolishness always comes to an end, and it almost always ends badly for a majority of the retail investors who believe the bullshit,” says Doug Kass, president of Seabreeze Partners Management and former senior portfolio manager at Omega Advisors. “It’s not rich versus poor. It’s smart versus dumb.”

Or maybe it’s just greed versus greed.

“They want Gabe Plotkin’s money, they want my money, they want Steve Cohen’s money. It’s a simple financial thing,” Left says. He acknowledges that we are in “the era of the retail investor,” and he hopes those investors will tread carefully, though it’s doubtful they’re listening to him.

“If one group of speculators wants to have a battle of wills with another group of speculators over an individual stock, god bless them,” said Neel Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, during a town hall event in February. “That’s for them to do, and if they make money, fine. And if they lose money, that’s on them.”

It’s an investing lesson learned over and over again—by high-rolling stock pickers with Bloomberg Terminals and by novices trading “stonks” from their couches.

Melvin Capital rebounded and posted a gain of more than 20 percent in February, though it reportedly ended the first quarter with steep losses. Cohen is back on Twitter, as is, inevitably, Musk. GameStop’s stock can still swing wildly on investor whims, and the company is making an effort to turn its business around. Just this week Redditors continued their battle with short-sellers, costing them some $848 million by driving up the price of GameStop and AMC again; losses stemming from the squeeze have now mushroomed to about $9.25 billion. Still, Left is determined to stay in the short game, albeit perhaps more quietly for a while. “You can’t tell a bird not to fly,” he said in a video posted online in March.

As for Roaring Kitty, well, he still believes in GameStop and thinks the suits betting against it are wrong, which he told lawmakers at a congressional hearing in February.

“In short,” he said, “I like the stock.”

This story appears in the Summer 2021 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like