Frank Sinatra Was My Enemy Who Called Me "Fat, Old and Ugly." Then, We Had Dinner One Night.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

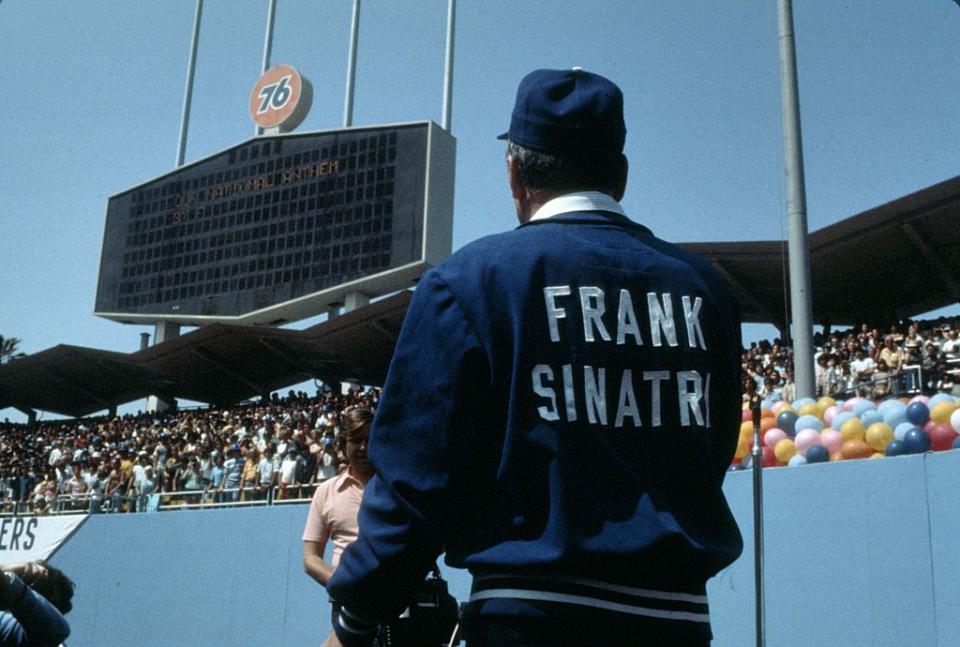

Frank Sinatra was one of the most influential music artists of the 20th century. His career took him from a skinny matinee idol during World War II, to the consummate interpreter of the American songbook. He never took his movie career too seriously but left behind a string of memorable performances (From Here to Eternity, The Manchurian Candidate). He was also one of the most sought-after celebrities of his time. As the leader of the so-called “Rat Pack” Sinatra also rubbed elbows with the mob and could be a vindictive bully. It is this Sinatra that gossip columnist Liz Smith took exception. She was unafraid to call Sinatra out in print, and then she became the target of his rage ... that is, until they sat down for a meal and everything changed. From the August 1988 issue of Good Housekeeping, here is Liz's recollection of her dinner with Sinatra. — Alex Belth, Hearst archivist

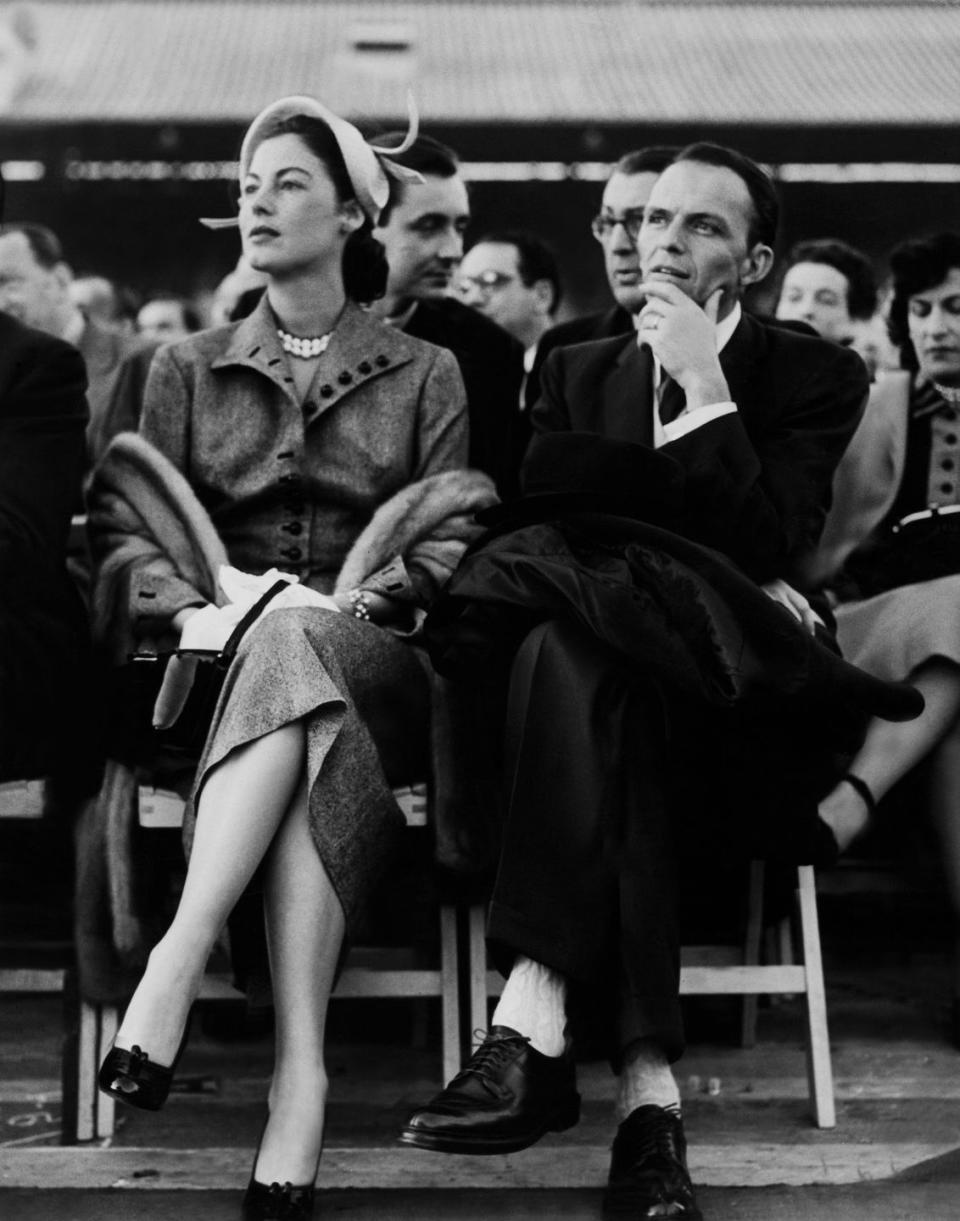

I had been in love with Frank Sinatra since I danced to the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra at the Lake Worth Casino back in the early ’40s. Those were my high school years in Forth Worth, TX, and Sinatra was Dorsey’s vocalist. On those memorable nights when the band came through town, our boyfriends would grow livid when we looked over their shoulders longingly, failed to hear what they were saying, and edged ever closer to the bandstand. So far, so normal. I was just another of the budding bobby-soxers who wanted to scream when Sinatra sang. I didn’t, though. I was determined not to be one of the crowd. I wanted Frank to recognize my sophistication and to understand my appreciation for his very great talent. I looked up at him, skinny and big-eared, standing before Tommy’s trombone, and sighed.

Then came the movie years when my friends and I would sit in the dark to our hearts’ content, memorizing his every look and action and inflection. I never sang a Sinatra song after that — even under my breath — without trying to employ Frank’s phrasing. My later appearances as an amateur singer with the Skitch Henderson Orchestra in New York City happened only because I was still imitating my idol. Skitch would say, “You know, Lizard, you can sing just like Sinatra. Too bad you don’t have any voice or range.”

So, my life went on, and I fell into journalism, writing and editing for magazines, and then becoming an entertainment columnist. By now we knew a lot more about Sinatra — what a leader he was, pal of presidents, chief of the Rat Pack, serious ladies’ man. We had devoured the drama of the Lana Turner and Ava Gardner years; now we devoured the stories about Juliet Prowse and Lauren Bacall. At this point, I was a relatively anonymous writer. But by 1975, I was a gossip columnist for the widely read New York Daily News, and a new responsibility developed upon me. Certain things were a must if you had the byline. I learned I was expected to take sides, take stands, make enemies, be brace and fearless, take my knocks and raps, and never wince or cry aloud. As a devout coward, this was the hardest part of the job for me, but I tried.

Through the years I had learned about a different Sinatra from the one I had originally worshipped, about a tough-talking and tough-acting guy who called women “broads” and “hookers,” who hated the press in general, and who often meted out revenge.

My column was not very critical of celebrities. I tried to give everyone a break. But when a celebrity phenomenon rose on the horizon, a person with real power, I would occasionally tilt at windmills. What’s more, I had come to feel that the Federal government, the Pentagon, politicians, televangelists, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time, Newsweek, and Frank Sinatra were all big enough not to be destroyed by my criticism. They seemed able to take care of themselves. And I began to be offended by Frank Sintara’s chutzpah, his hubris, his attitude toward women, his laxity in regard to the Mob. His volatile temper reminded me of my own feisty little father, and it wasn’t something I liked being reminded of.

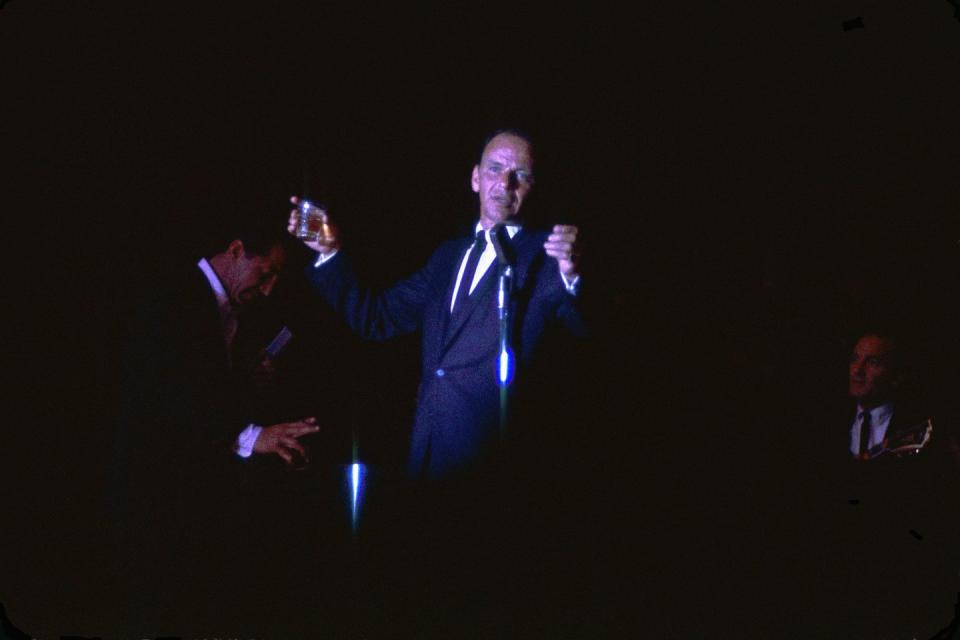

And so I defended Jonathan Schwartz when Sinatra had the deejay fired for criticizing his album Trilogy. I defended Barbara Howar, then a reporter for Entertainment Tonight, after she tried to ask him a simple, charming question at the Reagan inauguration, and he lashed out at her, saying, “You’re all dead, every one of you.” Then, when he began maligning Barbara Walters, saying she should turn in her press card, I called him a “bully” in print and inquired why he so often put down women. Sinatra immediately began attacking me with great gusts of venom from concert stages, even from Carnegie Hall.

I was, in his words, “a dog; all you had to do was hang a pork chop out the window” and I’d chase it. I was invariably described by him as “fat, old and ugly.” He said I preferred Debbie Reynolds to Burt Reynolds. I thought the Debbie/Burt wisecrack was pretty funny. I did like pork chops. But I was hurt by “fat, old and ugly.” I knew Frank was seven years my senior, and I didn’t figure I was any older, heavier or uglier than he was. (Neither of us was in the raving-beauty class any longer.)

I knew lots of people who loved Sinatra. Arlene Francis and her husband, Martin Gabel, were forever urging him to “let up on Liz.” One night Martin stood with him in the wings of Carnegie Hall and coaxed him to give it up. “Frank, you are a gentleman, and you are making a big mistake. Liz is a wonderful girl. If you only knew her…” Sinatra went onstage with smoke coming out of his ears and did 15 minutes on me, until a lady in the audience yelled, “Shut up and sing!”

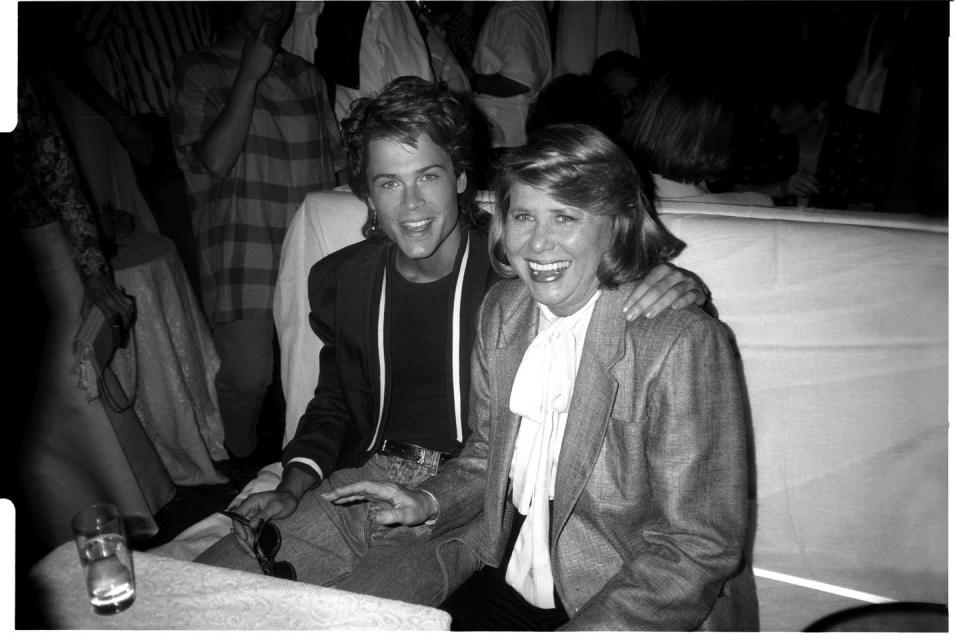

But it was my pal Sid Zion, the political columnist, who put the cherry on the sundae. He simply never let Sinatra alone about “the Liz biz.” He argued and cajoled. One day in the mid-’80s, Sid took me to Gallagher’s restaurant in Manhattan. As we examined the steaks hanging in the window like decorations, he said, “Liz, I think Sinatra’s softened up. He’s about to give in. He’s curious now. He can’t imagine how you can be as good as we all say you are, and he can’t believe he made a mistake in judgement.” I shrugged. By now, Sinatra was part of my fame. By becoming my sworn public enemy, he had made people interested in me, people who had never heard of me before.

I said to Sid, “Forget it. He’ll never like me. I worship his talent, but why would he care about that? It won’t happen.” Sid drew on his cigar and said, “Wanna bet?” Sure enough, three months later Sid called to say, “Sinatra’s coming to town. He wants a meeting with you.” I snorted. “No kidding,” said Sid. “He thinks maybe he done you wrong, and anyway, I think he admires you as a stand-up girl who wouldn’t be bullied or intimidated by him.”

The day came when Sid whispered into the phone, “Put on something pretty and be ready for me to pick you up at five-thirty. We’re going to Jimmy Weston’s to meet Frank.” I dressed seven times that afternoon. I threw my clothes around like a demented debutante. I was a girl on a first date. I didn’t know what to think. I was scared to death. Finally, I managed some demure outfit and climbed into the limo with Sid, who said, “You look nice. He’s going to love you!”

We stumbled into Jimmy Weston’s on East 54th Street. It was a throwback to the grand old crummy bars of the ’50s when men were men and women were glad of it. It smelled of stale beer and fried food. It wasn’t a grand place, in fact, it was tawdry and rundown. The choice signaled Sinatra’s loyalty to Weston, the proprietor. We approached one of the “rooms”— a small banquette walled off for privacy — and out shot Sinatra with his hand extended. “I’m so glad to meet you. Thank you for coming!”

“I am so thrilled to meet you, Mr. Sinatra,” I said, stuttering. He turned around, taking my arm and guiding me to the banquette. “Francis,” he said emphatically. “Call me Francis.” Under my breath, I think, I muttered, “Thank you, Mr. Sinatra.” We sat and made small talk with Sid beaming.

I was face to face with Frank Sinatra, the man who had beaten up journalist Lee Mortimer, had been linked to assaults on Jackie Mason, had devastated columnist Dorothy Kilgallen by calling her “the chinless wonder,” and had made countless women cry with his cruelty. He just looked intensely at me with his soft blue eyes, ordered more gin and tonics, and began to ask me questions. I talked and talked. I told him of my lovestruck days when he was with Dorsey, how I had followed his career from afar, how much I loved him in movies, how he was the greatest singer of his time. I tried to stop myself, but couldn’t. Of course he was used to it all; all his fans did it.

He'd nod and ask me a question. Where had I come from? Why had I become a gossip columnist? What was it like to grow up in Texas? I told him about reading Milton Mezzrow, the musician who wrote the first enlightening words I’d ever read about jazz and the life of a musician. He knew all about Mezz. He told me about the long phone conversations he still had on a regular basis with Irving Berlin. I told him that Mr. Berlin had sent me a note reading, “I see your column every day, kid. Keep up the good work!” We talked about Elizabeth Taylor and Lana Turner. We talked about Ava Gardner and how my then-aide St. Clair Pugh had known her back in Smithfield, NC. I told him of my adventure with the famous bandleader Artie Shaw, when he tried to take me to bed, but I couldn’t because I was intimidated by the women of his past — Ava, Lana and Kathleen Windsor. Sinatra loved that.

“Why, that old lech!” he exclaimed. He didn’t care for Artie Shaw. We talked about philosophy, history, art, books, and our dogs. I admired the Alexander the Great seal on his ring and asked, “No more worlds to conquer?” He liked that and launched into his view of history. We had another drink.

He said, shyly: “I’d like to help you with your charity for literacy. I am impressed by that work. Just call me anytime … also, if anybody ever bothers you, just ask me and I’ll fix it for you.” For a moment, I had visions of sugarplums and literacy money dancing in my head before I snapped to and said, “Thanks, but…” He interrupted. I needn’t explain, he understood. I couldn’t take favors. But I wasn’t to consider anything a favor. He just liked to “fix” things for his pals. All of a sudden I was his “pal.” I almost fainted.

I loved him. I had a feeling for what it would be like to be in his strong and capable arms. (He wasn’t frail and skinny anymore.) And he was the most immaculate man I’d ever seen — beautiful French cuffs, a fantastic silk tie, wonderful hands with clean strong nails and sexy wrists. (I’d always been a sucker for wrists.) I loved his smell, the scar on his face. I imagined a headline or two: SINATRA ATTACKED BY OLD BROAD IN SALOON … SINATRA CHARGES GOSSIP MOLL WITH SEXUAL HARASSMENT.

After two hours we both knew we had to go. We ambled toward the door. On the street an old woman screamed and threw up her hands, yelling, “Frankie!” She moaned. He took her in his arms and kissed her. “Darling, you look wonderful!” he said. Then he had his chauffer take me home while he chatted all the way. We kissed good-bye.

As he drove away, I realized I had thrown all judgement to the wind. I was Sinatra’s slave. Co-opted by a couple of gin and tonics. His for the rest of my life. And neither of us had even mentioned our past differences. We were too genteel for words.

The next day, as I swooned about my office in a kind of trance, the most beautiful Phalaenopsis Moth orchids arrived with a handwritten note, signed “Francis Albert.” Then came a letter thanking me. I think that one was signed “Albert Francis.” In the years after, I received a number of fabulous notes from him, and occasionally, more orchids. I was invited to his 75th birthday party at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and seated only a stone’s throw from his old friend Claudette Colbert. I sent him stuff about his hobby, miniature trains. I sent his wife, Barbara, pins that read I AM MARRIED TO A TRAIN NUT. We became pen gals. Every day I prayed Frank Sinatra would never insult anybody else I loved or admired or do anything untoward that I would have to write about.

I was lucky. He didn’t. I saw one of his last concerts at Radio City Music Hall with four of the best seats in the house provided by him. I took his old enemy Barbara Walters. When I told him later, he just laughed and said, “That’s swell!”

So, I stopped being objective when it came to Frank Sinatra.

Love is funny that way.

You Might Also Like