The Forgotten Chinese Passengers of the Titanic Inspired This New Novel

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

In the fall of 2017, an email appeared in my inbox. It was one of those forwarded group emails my Chinese Canadian mother-in-law enjoys sending me of interesting articles she’s come across, the kind I usually hold off on reading until...well, later. As a writer of historical fiction often centered around Asian Americans, I have become a repository of news clippings for family, friends, and complete strangers. But this one caught my eye. Fwd: NEW FILM REVEALS FATE OF CHINESE SURVIVORS OF TITANIC. I squinted hard, wondering how the words “Chinese” and “Titanic” might belong in the same sentence.

Surely, I hadn’t read that right. I had never heard of any Chinese people sailing on the Titanic, let alone survivors. And judging by all the emphatic responses to my mother-in-law’s email from her family and her friends—senior citizens like herself—no one else had either, even the ones who had visited Titanic museums like the ones in Belfast and Pigeon Forge, TN.

The article informed me that there were actually eight Chinese passengers sailing on this ill-fated ship, seamen bound for a new route in the Caribbean. They were the largest group of non-European or North American passengers sailing on the ocean liner—and a remarkable six of them survived.

Why had I never heard of these passengers? And how did the 75% of them survive, when the survival rate for the third-class passengers was more like 25%?

These questions bothered me. But I was in the throes of writing The Downstairs Girl, a YA book centered in a different part of the world and a different century—Atlanta, 1890—and I didn’t have space in my brain to nurture a story set in the cold waters of the Atlantic. In fact, I didn’t think I could write a story about the Titanic at all, even once I finished the current book. I didn’t know much about the Titanic beyond what I remembered from the movie (specifically: not enough lifeboats, major classicism, and the outrage of throwing a perfectly good diamond necklace into the sea). And though I loved a good ocean-faring story, I felt ill-equipped to write one, given my propensity for seasickness and general lack of knowledge as to how ships work.

But as much as I tried to elbow away thoughts of the Chinese on the Titanic, the idea had already begun to take hold. Here was an opportunity to bring attention to a story that had not yet been told. Here was a chance to show others the far-reaching effects of the Chinese Exclusion Act, an act that from 1882-1943, prohibited Chinese from coming to the United States.

For that is the reason you have likely never heard about these men. Every Titanic survivor—705 in all—was allowed entry into the United States without question and given aid and medical relief. After all, all papers and money had been lost in the catastrophe. But not the Chinese. They were sent away within 24 hours of arriving in New York, simply on the basis of race.

They were sent away within 24 hours of arriving in New York simply on the basis of race.

Worse, they were shamed for surviving. Newspapers vilified them as "cowards" who had hidden under seats to survive. For Chinese people, being shamed is often considered a fate worse than death, so many of these survivors did not tell their stories to their families—another reason so little is known about these men.

Researching this book wasn’t easy. There was lots of information on the Titanic—but not so much on the Chinese passengers. The film The Six had not yet been released, and the British documentarians did not respond to my requests for information. With so little to go on, I focused my efforts on learning about the Chinese sailors working in England during this time. Many of them came from Hong Kong and Guangdong. They probably spoke little English. After the iceberg hit, they probably hadn’t understood the emergency orders from the crew, and with chaos swirling around them, they likely tried to do what they could to survive: get themselves on a lifeboat.

Actually, the last person recovered from the Titanic was a Chinese man. He was found floating on a door. In fact, his plight inspired the scene in James Cameron’s movie, in which Rose survives by clinging to a door (and infamously not sharing said door with Jack). The crew was reluctant to pick up this last Chinese man because they thought he was a “Jap.” But it’s a good thing they did, as he ended up rowing the lifeboat to safety.

By showing the people who don’t get the spotlight, I can make you wonder about them.

Readers ask me, "Why do you choose to write about these stories that have fallen into the cracks?" Because by showing the people who don’t get the spotlight, I can make you wonder about them. Maybe even care about them. And if I can do that, maybe you’ll start looking for them yourself in those cracks, in those dark corners, in those hidden places.

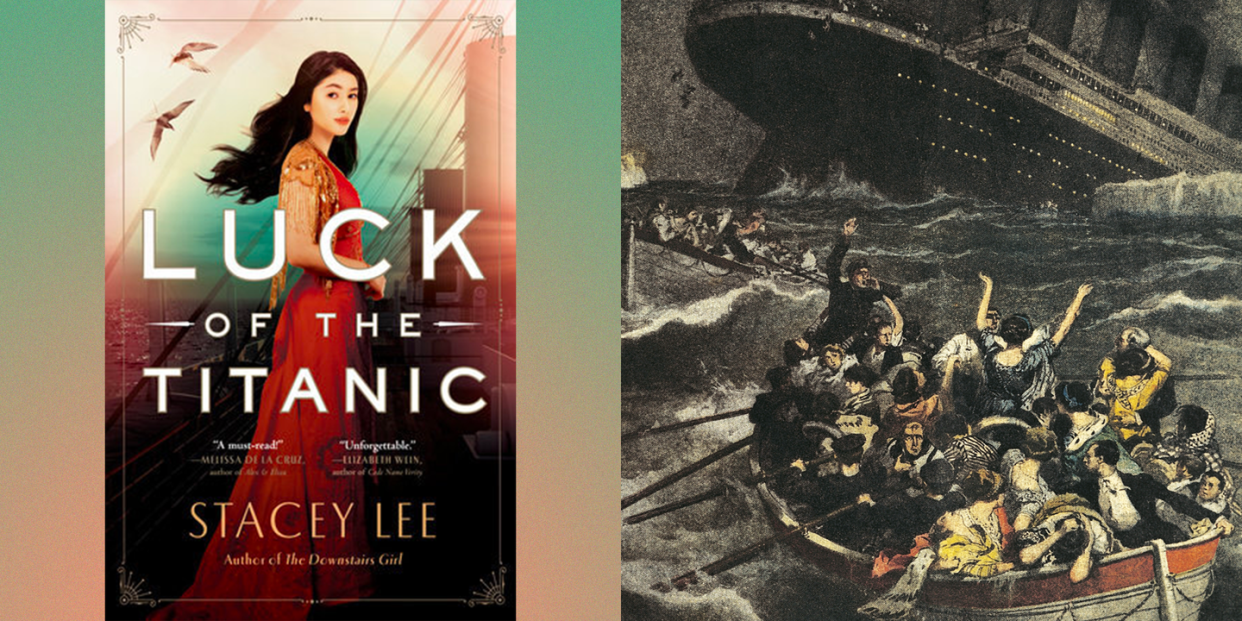

My novel Luck of the Titanic is not the true story of the Chinese passengers on the Titanic. It is the story of the acrobat Valora, a British Chinese girl who boards the Titanic hoping to convince her twin brother, a sailor traveling with his company of Chinese seamen, to audition for the Ringling Brothers Circus and go with her to America. I am a novelist, a literary entertainer, after all, and the true story of the Chinese passengers is not known. But even if what happened to them is never known, hopefully Luck of the Titanic will give them a permanent place on the ship of dreams.

Stacey Lee is the New York Times bestselling author of the novels The Downstairs Girl, Luck of the Titanic, Under a Painted Sky and Outrun the Moon, the winner of the PEN Center USA Literary Award for Young Adult Fiction. She is a fourth-generation Chinese American and a founding member of We Need Diverse Books. Born in Southern California, she graduated from UCLA and then got her law degree at UC Davis King Hall. She lives with her family outside San Francisco. You can visit Stacey at staceyhlee.com or follow her on Twitter @staceyleeauthor.

You Might Also Like