Feeling Like A Literary Imposter, or How I Accidentally Became An Author

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

This is like one of those moments in a movie–the frame freezes and a record scratch sounds. Then the voice of the narrator comes in, "That's me, and I guess I'm here to explain how I got here, how this story happened.” Well, that's me and I guess I'm here to explain how I got here, how this story happened.

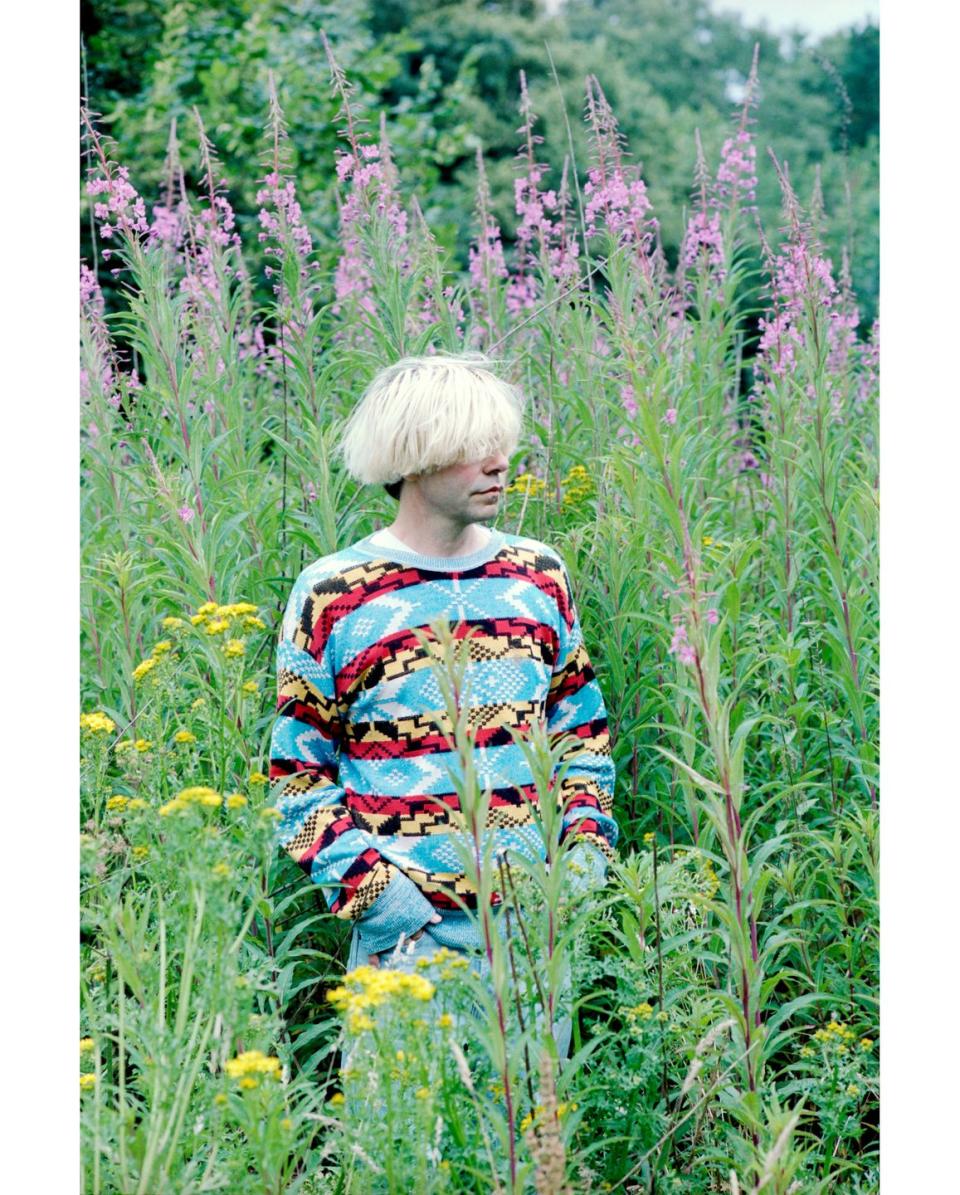

I accidentally became a singer. Of course, it was something I did and that I enjoyed but had I told my career officer at school that I would work professionally as a vocalist for upwards of 30 years, I’m not sure whether it would have been deafening silence or gales of laughter that would have greeted the statement.

Perhaps, the only thing to elicit a bigger reaction would have been a conversation with my old headmaster outlining the fact I’d also carve out a career as an author, with five books published and another one on the way–in that case, I’m not sure who would be more taken aback at the thought, him or me.

When I was growing up, singers lit up our TV screens like beautiful butterflies–our family would gather around the television and marvel at Bowie, Bolan, Dusty, and Elvis—they were otherworldly; it wasn't a career to aspire to for a kid from the uneventful village of Moulton in Cheshire. But my eyes were opened to a magical world. Punk came along when I was 10 years old, and those far-flung planets were brought closer to earth. Music was suddenly somehow more democratized, an actual possibility. And then a band came along that changed everything for me–two members were from Salford, where I was born, and two from Macclesfield, a slightly less sleepy town, near enough to Moulton to make me dream. That band was New Order and I studied their every move, hoping and wishing that I could work out the secret formula that would transport me, Alice-like, into Wonderland.

I formed a band then another, I grew sideburns, got rid of them, sported a quiff, tried to write songs, tried to record songs, hung round a record shop, played a few shows. Then my band supported an up-and-coming outfit called The Charlatans at a small venue. Their singer was having doubts and the rest, as they say, is history. We saw success and tragedy, we traveled the world and our adventures became mythical–mostly through our own retelling of them.

This piece isn’t about all that. This piece is about how I stepped out from that world and into another. In my romantic worldview, it started with how I imagine the recruitment process works in the world of international spy rings. I was minding my own business while DJing, and I was aware of a shadowy figure, we'll call him 'Red Squirrel'–not for anonymity or protecting his identity, just for the upbeat, entertaining purposes of this feature.

"Hello Tim," said Red Squirrel. "You don't know me, but I work for Penguin."

So far, so MI5.

But Penguin was no codename–there was no veiled secrecy. He was literally from Penguin, the giant book publishing house. I was taken aback when he said he'd like to speak to me about me becoming an author, writing my memoir. It was like being stopped in the supermarket by someone from the Human Resources department at NASA, telling you they’d like you to consider being an astronaut.

These were the people who published The Catcher In The Rye and To Kill A Mockingbird. Was I fit to be added to their list of alumni? Doubtful. Was I going to give it a go? Definitely.

I'd spent more than 25 years making records and partaking in many of the pastimes on the rock star to-do list. My world was recording albums for labels, so I just had to skew that view–the label was now Penguin and the album was my life story, no music, just the words. A daunting task before you even consider whether people would want me to include them in tales from the high seas of the music world–or whether my memory was up to the task.

First, I needed a system. With the band, we’d write together, share ideas, and have a producer to bring everything together. This time I was on my own. In my mind, the likes of Hemingway would get up in the afternoon, take on board a few cocktails, head into the yard to shoot bottles from a fence post, drink more cocktails, then spend an evening hammering away on a vintage typewriter while inspiration swirled around him like a swarm of mosquitoes. I was more of an early riser; I’d recently given up drinking and my access to firearms was limited.

Time passed, an advance was paid, and inspiration and motivation were far-off lands I couldn’t quite acquaint myself with. I wrote songs, we toured, life came and went, and the pages remained blank. Meetings were attended, Red Squirrel would arrange a rendezvous in a coffee shop and I’d excitedly regale him with my endeavors of the written word. But I was kidding myself, and I’m not sure he was as easy to convince.

People in bands often talk of the feeling of imposter syndrome—we get how other people got where they did but we just kind of hum melodies, write words that fit, and record them. Yes, we generally love the process and the results but it’s sometime hard to imagine that anyone else would. Still, it’s something you get used to when audiences buy tickets and albums. This wasn’t imposter syndrome—I was literally an imposter. The advance for a book had been sent over but there was no book. Not only had I never navigated those seas before, I hadn’t even left land. And, to overstretch an analogy, I had to weigh anchor and set sail.

A song has a form of completeness and parameters to follow. Four minutes, choruses, verses and a middle eight. Maybe a spoken word bit. I knew my way around but my survival skills in prose were unproven.

But nobody knew of the book outside of a select few people and that gave me hope. If it was terrible and unreleased, then we had an agreement that it never existed; we would speak no further of it. The advance would be returned and my life as an author would be over before it began. (I decided not to share this agreement with the publisher as confidence might plummet, but it gave me a jumping off point. Maybe that’s all I needed.)

I spent a few days talking over what would hopefully become the start of my magnum opus–I had in mind two films to set the tone to give myself a pointer in terms of atmosphere: Stand By Me for when I was describing growing up, literally becoming the Richard Dreyfuss of my own story, and then for the high-octane caper element of life in a band, the 1969 version of The Italian Job was my touchstone.

I had a few pages of notes, all in capital letters, no punctuation. Reading it was like being shouted at by someone who had been up all night. I had a thought to just get started, to address the reader, and to even reference that this wasn’t a book until they were holding it in their hands. If it was and there were multiple pages after the one they were reading then I’d done it, if not, it was no issue as they wouldn’t have it in their hands anyway. It was Shrödinger’s book—it existed but at the same time, it didn’t. So far, so meta.

I’d found my way in and was soon to establish my method. Recording studios are such that, despite the best efforts of procrastination, once inspiration hits, there is little inertia to stop it mid-stride; and we had such a studio, in Cheshire, not far from where my story started. The impetus was there; a lack of windows means time can become irrelevant, enough solitude to keep distractions at bay and the ever-increasing frequency of emails from Penguin, wondering whether the seed of their advance was ever going to bear fruit.

I’d start early morning, take a break for a walk and work late into the night, sometimes through to the next morning. Like a montage sequence in a film, I’d be typing while laying on the floor, ponderously staring into the middle distance, throwing screwed-up sheets of A4, basketball style into a wastepaper basket. Google was my companion, checking dates, looking at tour posters, piecing together 30 years of stories like a film noir gumshoe detective while never knowing if my endeavors would see the light of day. I’d arrive at the studio on a Thursday evening, fresh pack of coffee in hand, then work until Monday morning, filing my efforts over to a Penguin email address before heading back to my regular life. It was like sending a message in a bottle from a desert island—not quite knowing if the missive would ever make it across the ocean. No replies came back and I took this only to be bleak news, but I found out an extraordinary thing a year or so later on the launch night of my autobiography. *Spoiler Alert*: I actually finished it and it became a real-life book, a best-seller even.

Anyway, on the launch night, at a beautiful church near Piccadilly in London, the head of Penguin Books stood up and made a speech that alluded to the fact that after months and maybe even a year or two of nothing, emails would arrive from me, often on a Monday morning. And they became a highlight for the people who worked there. Even ensuring that normally haphazard punctuality was shoved aside just in case another few chapters had landed. It was the first I knew, and the decision had been taken, rather than give any guidance, just to wait for the next draft each Monday, without any interference from them. I was flabbergasted, relieved and proud all at the same time–having taken on something that was so far out of my comfort zone, sure that the efforts might have come to nothing in the end. The reviews came in, quotes were plucked from them and shared on billboards and the sales clocked up, and that chapter of my story literally came to a close.

In music, there is talk of the “difficult second album,” but it’s nothing compared to the “difficult second autobiography.” With Telling Stories, I’d written about 45 years of my life, arguably the most exciting years. If a second volume was to come out when I was 90, then I’m guessing that the pace would be a little slower.

But I had been bitten by the writing bug.

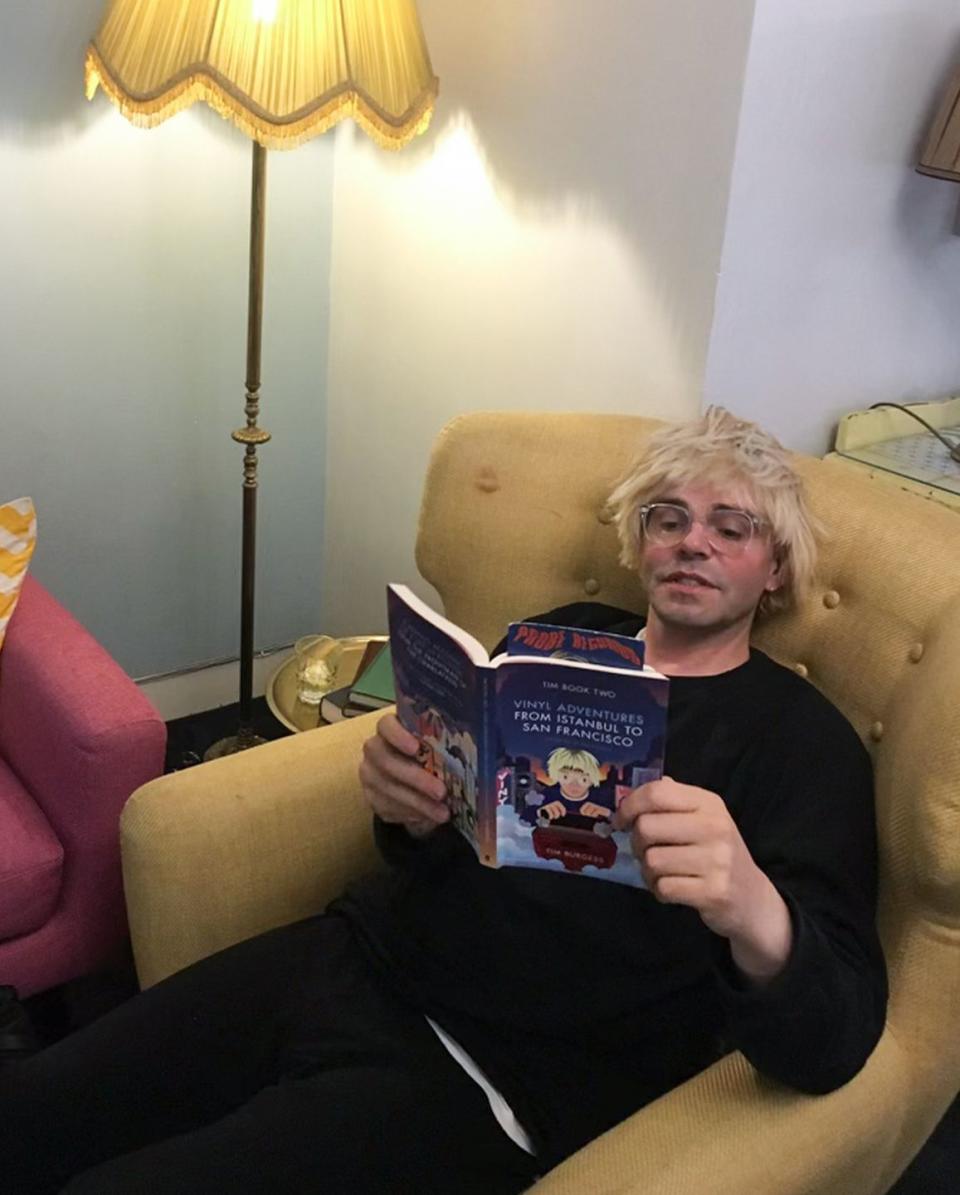

Then news came in that the people at Faber & Faber were fans of the first book and were interested to hear any ideas for a second. I had one idea, that it would be called Tim Book Two. This alone set social media alight for a day or so as I got my plan together.

One of the first rules that gets mentioned is “write about what you know,” so that narrowed the field slightly. I decided to make a list:

Records

Record shops

I was about to head out on a European tour with The Charlatans, and a plan started to form. My suggestion was submitted: A “state of the nation” look at record shops around the world–vinyl was making a comeback and shops had started to open up rather than close down. And this would be done via a bit of an odyssey; I would ask people I knew from the music world and beyond, to choose an album, and I would track it down on vinyl to add to my collection.

An instant reply came back: We love it! Tim Book Two: Vinyl Adventures from Istanbul To San Francisco was the title of my next effort. My confidence had grown as the reviews of Telling Stories came in. Writing is literally about communication, and it doesn’t matter whether that form is song, poetry, or essays. So, Johnny Marr, Iggy Pop, Sharon Horgan, Ian Rankin, and a whole host of friends chose one record and I managed to find them all in various vinyl stores around the globe; only travelling while touring. (Budgets and carbon footprint had to be considered.) The book became a tour, a record fair, a turntable, and even a double album. I laid down my metaphorical pen and thought that would be that.

A third volume was to follow, One Two Another—I know! Pressure was on for these titles now, never mind the actual content. Sticking to the mantra of “write about what you know,” it was a collection of lyrics and an attempt to analyze my writing process. It was a more emotional experience than I thought, and by now it was approaching a decade since Telling Stories and some of the biggest events of my life had occurred–Jon Brookes, The Charlatans drummer had died, and my son had been born. They began to feel like a series of albums; a theme for each but nothing to really curtail any ideas. And as people discovered each one, they then skipped to the others in no particular order.

I genuinely was going to finish at three books. I’d played my part as an author and I was ready to leave that world behind. Then, along came a global event that would change everything. Nearly 10 years before the pandemic, I had an idea that would make use of my nascent Twitter account. While watching the movie Four Lions on TV, I saw a tweet from Riz Ahmed, one of the stars of the film. He explained the background to a scene which added another dimension to watching. It hit me like a bolt from the blue: What if we took that approach with an album?

A track-by-track commentary via Twitter as the audience listened to the album in question. This was before the advent of streaming, so anyone taking part had to have access to the record, but that was fine as our Listening Parties would feature my solo albums and those of The Charlatans.

Fast forward to March 23, 2020, and the announcement came that everyone had to stay home. Everything was canceled. The world came to an abrupt standstill—everyone searched for something to do. I tweeted that we could start The Listening Parties again, guessing we had a couple of weeks to fill. We started with The Charlatans' debut album, Some Friendly, that very night, and Alex Kapranos, from Franz Ferdinand, pointed out that he’d bought a copy of Some Friendly with his birthday money that year. A quick message to Alex, asking if he’d like to host a Listening Party, and we were away.

We’ve now done 1,211 albums—with hosts including Sir Paul McCartney, Run The Jewels, Kylie Minogue, Iron Maiden, and Duran Duran. They took on a life of their own and my fourth excursion as an author came via a message from Dorling Kindersley, offering to make The Listening Party into a book. Volume I came out last year, and Volume II is out now, with royalties supporting The Music Venue Trust. (Also out this year: Typical Music, my sixth solo album.)

So that is my story of going from accidental singer to fortuitous author, but like many of those movies with the record scratch moment, there’s a twist.

In July 2020, I wrote a fairly innocuous tweet:

Idea for book.

Closer.

A study of the final tracks on albums.

I’d deffo read it, maybe I should write it ; )

And within a couple of days, a publisher had sent an offer in for what’s going to be my sixth book. As with my first attempt, I’m just typing this on my laptop. Will it ever become a feature in Esquire or did they have reservations about their offer? If you’re reading this, then we can safely say that it did. And if you made it this far, may I be so bold as to suggest that you might enjoy any of the five books that are currently out there in the world.

You Might Also Like