Fariha Róisín on the Healing Power of Poetry

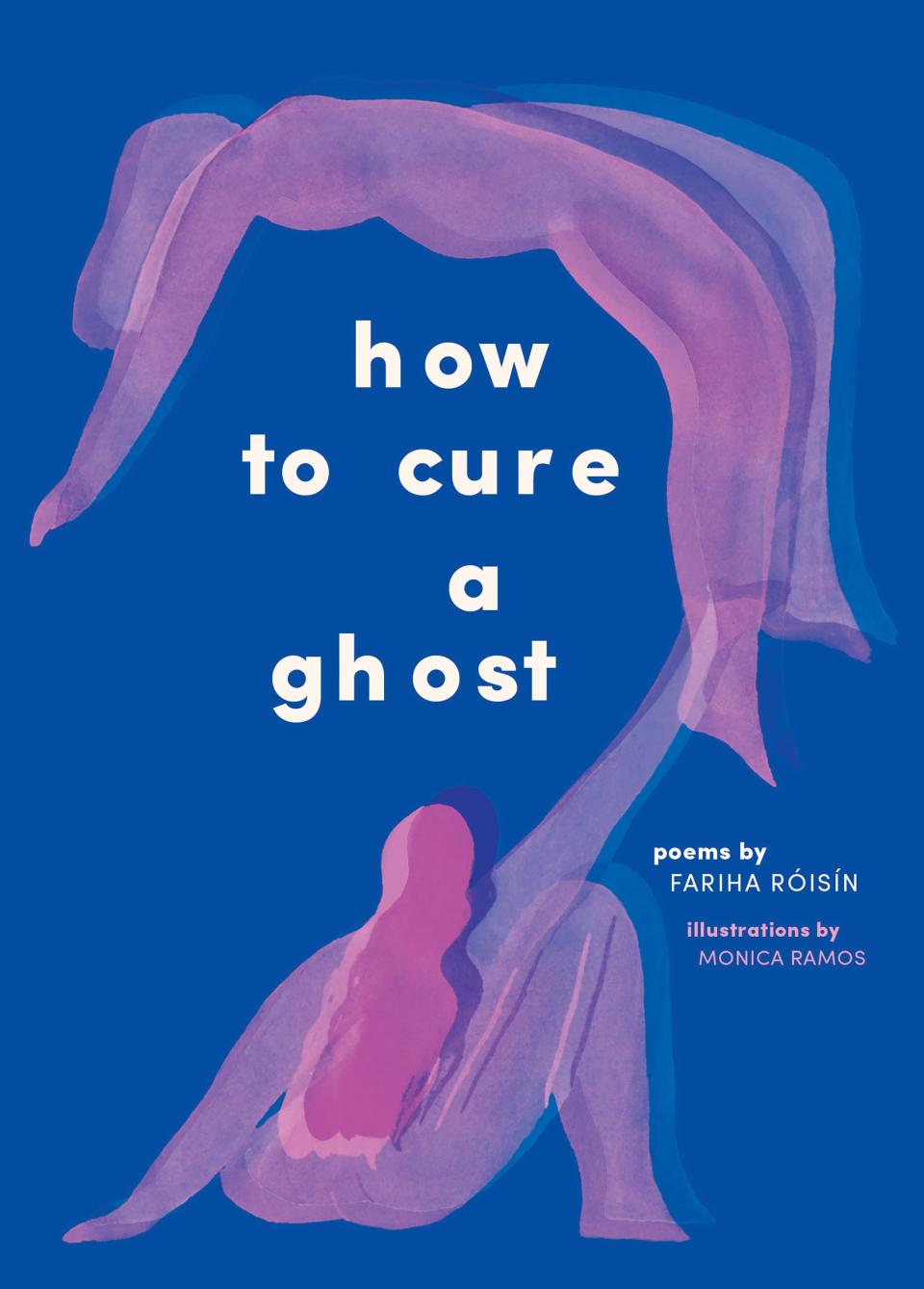

Fariha Róisín’s piquant essays explore racism, faith, queer identity, and misogyny. Now the Brooklyn-based writer is diving back into these ideas via a brand-new medium: poetry. On September 24, she releases How to Cure a Ghost, a collection of poems that aims to heal—both herself, from the traumas she’s experienced as a queer Muslim woman, and readers who have experienced similar types of oppression, whether sexually, physically, or emotionally. She calls it a book for survivors. “The ‘ghost’ is so much,” Róisín tells Vogue of the title’s meaning. “The ghost is colonization, my mother, white supremacy, abuse, ancestral trauma. Even though all of these themes are broad, they really come back to human pain. We’re all suffering in a way, so how do we heal? We heal by naming the ghost.”

Róisín is the definition of a multihyphenate; she writes fiction, does astrology readings, models, and is dabbling in upcoming TV and film projects as well. But she felt the new lane of poetry was an illuminating fit for the subject matter she wished to touch on. “In a weird way, poetry is a canvas that allows you to be hyperreal,” she says. “Because it is so beautiful, people are much more willing to accept it. There’s a digestibleness to poetry that creates a trust with the reader.”

Over the course of five years, she delved into a variety of personal experiences for these poems, from being objectified for her race—“Or when they tell you you’re pretty/for an Indian girl,” she writes in “The Many Descriptions of Being Brown”—to being mansplained to by white men. The resulting poems are certainly beautiful, but the topics at the heart of the book are, as Róisín says, heavy. In “What 9/11 Did to Us,” she recalls her experiences with Islamophobia as a Muslim woman: “Do you know how many times/My friends have said offensive things to me?/Asked me questions that have made my skin scream.” It’s a tension she has been dealing with for a while, she says: “For the longest time, I don’t think I even felt comfortable declaring that I was Muslim. That was so hidden; it was such an embarrassing thing. In my early 20s, I really had to reconcile that and say, ‘No, this is my identity.’ I had to learn to feel good in it.”

Róisín also approaches many of the darker themes in the book with humor—something that, like poetry, can be an effective way to grapple with emotions that might otherwise be too daunting. “Humor is such a fantastic tool to get under people’s skin in a way that they didn’t even expect,” she says. “Great comedy just hits you in the gut.” In “All the Things We’re Actually Thinking When Men Think We’re Staring,” she turns the tables on objectification courtesy of acute observations like, “Definitely a serial killer” or “Lol that guy looks like an ugly Adam Driver?” In her one-sentence poem “To the Aunties,” she also takes aim at toxic family members, writing, “Watch your own children first, innit.” (She tells me the original poem was just going to read “Fuck you.”)

Ahead of the release of How to Cure a Ghost, Róisín shared an exclusive new poem with Vogue, titled “Bad Men Keep Bad Men Keep Bad Men Cool.” Her exploration of men not always being who they seem is a perennial one, but lands amid the #MeToo era: “We live in such a society of rampant misogyny,” she says. “We see this everywhere; with trans women and aboriginal women in Canada being the most murdered group of people. Women are victims of incredible violence in this world and it’s just accepted.”

Below, read her poem in full.

“Bad Men Keep Bad Men Keep Bad Men Cool”

i thought bad men

hid in woods,

disguised in wolf costumes

bloodthirsty

strangers with candy

hollering like dogs

outside schools

slipping hands up

short dresses

watching asses

rumble as they shake

up stairs

using handycams to

capture a cheek

all bravado,

cum-stained car seats.

i thought bad men were

senators, politicians

trump and fox news

“reporters,”

anti-Semites, neo-Nazis,

punch him in the face,

richard spencer,

religious zealots, zionists

trans-misogynists, homophobes

mansplainers—

i heard egon schiele was abusive,

and l. frank baum and

h. p. lovecraft hated

black people

and, oh, don’t even get me started on

“male novelists.”

heathcliff and rochester

both had rage issues—

the brontës knew.

i thought bad men

looked like willem dafoe

or crispin glover

in charlie’s angels;

the dark-haired bad boys

who do backflips.

motorcycle jackets,

badlands killing sprees

across, and down

all manner of highways

gilded with angled noses,

flared nostrils

lips that would embrace

you, as if swallowing

you whole,

exterminating

your existence

through a kiss;

a dementor draped in flesh.

i didn’t think bad men

would mask themselves

as good men.

that they would

never announce themselves

as bad, or merely

present themselves

as good—until

it no longer served them.

pathetic until the end,

i didn’t think a bad man

would take away my virginity

with a throbbing blunt thud

never call,

or get me pregnant,

or tell me that i’m a dramatic cunt

that all kinds of women

get abortions, “it’s not a big deal.”

bad men do what bad men did

for centuries

because that’s what bad men

like bad men do.

they walk away from the

dangerous swamps of indignation

they create,

the cuts, broken kneecaps,

the crazy they mythologized,

then nurtured, gaslighting

slow death, the ugly

self-hate they weave

into bodies, they deem

weak. belonging to no one.

and once you learn

what bad men do

you carry that uncertainty

along with

all your other baggage,

looking for a sign

like a flashing neon light bulb

this man is bad

and even then you only barely

begin to understand

even though you find

you almost always

knew. all along

goddamn:

just trust your gut, bitch.

When you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Originally Appeared on Vogue