A Fantastical World of Art and Hospitality in the Heart of Tulum’s Jungle

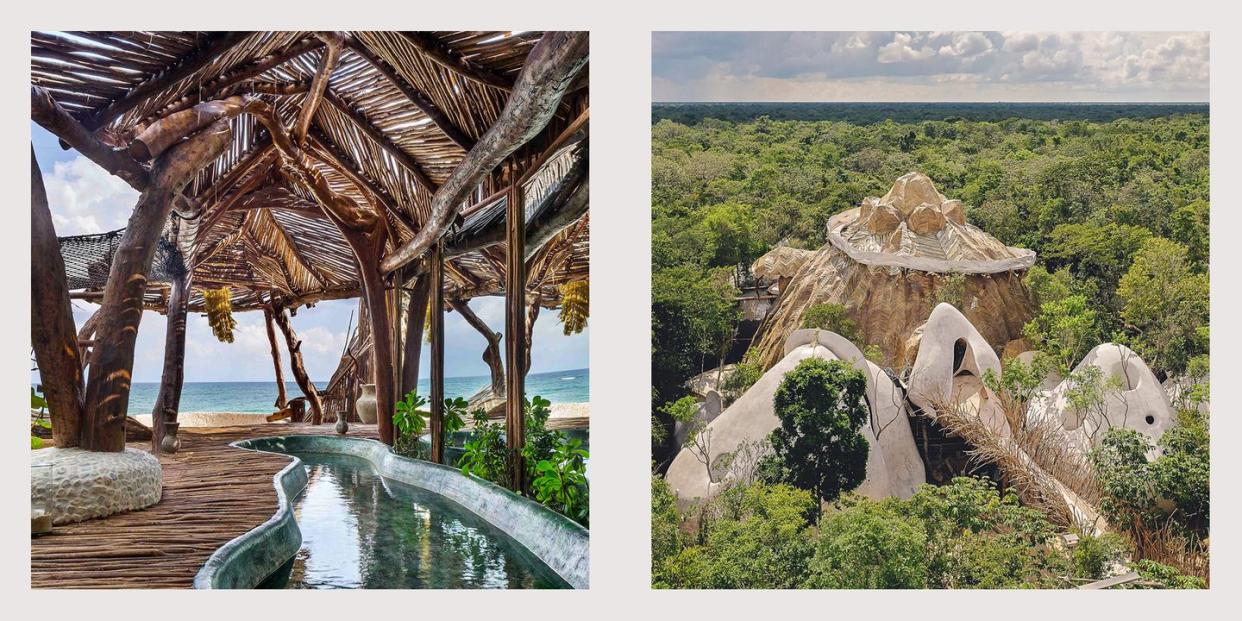

From above, it looks like a giant’s game of pickup sticks, with its explosion of vines, branches, and straw. At ground level, it soon becomes evident that this is a visionary’s kaleidoscopic creation, and a luxury one at that. Among its offerings are spiritual cleansings, gourmet dining, full spa services, luxury shopping. Hop over to the beach for a Mayan rebirth ceremony by day; indulge in a five-course chef’s menu from a floating nest by night.

AZULIK is full of surprises. The resort compound—founded by visual artist Eduardo “Roth” Neira—is situated on Tulum’s popular hotel strip along the Yucatan Peninsula, where many of the town’s international visitors convene to enjoy quaint-yet-lavish vacations just far enough away from Cancun mania and spring breaker chaos. While many things have changed in Tulum over the past two decades, Roth has been pushing his mission from the start. When AZULIK was originally built, the surrounding area was still a hidden piece of paradise and one of the country’s best kept secrets. With its easy access to archeological sites and pristine, white sand beaches, Tulum has since become one of Mexico’s most popular destinations, each year raking in more visitors than the one before.

But like many beach towns that make their way into the mainstream orbit, Tulum’s fragile ecosystems have, over the years, been pushed to their limits by mega resorts and luxury hotels that sit upon the delicate shorelines, causing all sorts of environmental damage. Unlike the new slew of ecological pseudo-saviors, however, Roth and his team have been pursuing a mission of preservation and harmony for the past 20 years. Though not formally trained in architecture, Roth grew up in Argentina with two architect parents, and after moving to Tulum, teamed up with the indigenous Mayan communities who have been building on the jungle’s dense landscape for centuries.

Without blueprints, Roth and his team worked—and continue to work—with sketches that are then translated onto the natural landscape. Unlike traditional building, which requires tearing down the landscape and creating a stable, artificial surface from which to build upon, AZULIK sits atop stilts, allowing for nature to remain alive beneath it. “When you flatten and level the land, you end up building on a cemetery,” Roth tells us. Without straight lines or flat surfaces, AZULIK was built. Polished concrete, twisted bejuco vines, and thatched roofs make up the majority of the hotel’s architecture, with winding paths designed to relate to the curvature of the earth. While the original structures at AZULIK were considered to be direct replicas of the Mayan palapa (the traditional style of roofing), the techniques have changed over time to allow for more creativity in its construction. Now, by adapting to the landscape as they go, Roth and his team rely on trial-and-error to intuitively build every inch of the property.

It’s an approach that might distress any traditional architect. Roth explains that this improvisational strategy is ingrained in indigenous craftsmanship, noting that the Mayans he works with “have the humility to see that these things aren’t complicated.” Unbound by the contemporary rules of architectural design, the resulting spaces align with nature’s existing structural logic. “I want to emphasize that my inspiration was and is the obstacles themselves," Roth says. “Since we use no tactual blueprints, we are free to think on our feet and incorporate new ideas as they present themselves. Sometimes, we end up with something quite different from what we envisioned at first, a new reality shaped by conceptions that are constantly evolving.”

The hotel’s villas—which range from the moderately priced Jungle Villa to the sprawling, butler-equipped Aqua Villa—are designed without lighting, showers, or air conditioning, and instead encourage guests to take baths, cool off by sea breeze, and power down along with the sunset. Bedding from the suites is recycled and used for Roth’s fashion line, which he sells on the property; food scraps from the hotel’s three restaurants are used to dye various textiles; fallen trees are recycled as repurposed for new structures throughout the two properties. Once guests leave their personal quarters, it can be easy to get lost, but with every wrong turn through the maze-like property, it is likely to stumble upon something worth stopping for. The spa, for instance, with its polished stepping stones, waterfalls, and cascading vines, leads to a spherical yoga dome where classes are regularly held. Cross one of the rope bridges and you’ll find restaurants serving an impressive array of delights. Other highlights include retail shops—IK_RAUM, ANIKENA, and most notably, ZAK IK—which currently serves as the boutique for the fashion house’s J’adior Tulum capsule collection.

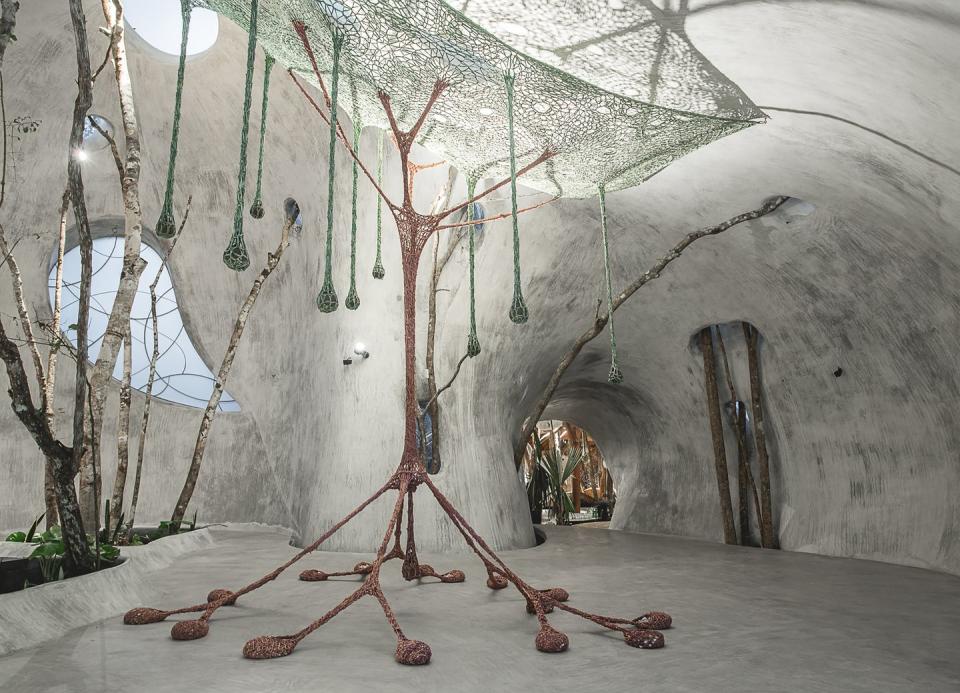

Though Roth is a successful hotelier, his ambition for building AZULIK has always been fueled by the wish to fund a range of artistic endeavors. At the center of this is Uh May, an “interdisciplinary creative sphere” located just 30 minutes from AZULIK in the nearby jungle. While its architectural style mimics that of the hotel, Uh May is also the grounds for a contemporary art museum, SFER IK, Roth’s own home, and a space to hold artisan workshops for Mayans and visitors alike. Spiraling paths and curvilinear walkways connect a series of cement domes, including the central structure that houses the museum’s exhibitions. According to Claudia Paetzold, SFER IK’s curator and artistic director, “People patronize museums because there are normally so many markers of authority when you enter.” At SFER IK, security checkpoints and ticket taking are exchanged for spiritual cleansing and the removal of your shoes, connecting visitors—quite literally—to the earth. The museum feels reminiscent of the Guggenheim on a psychedelic trip, and throughout the space, artwork comes in many forms. Unlike traditional institutions, which function as sterile white boxes upon which art is hung, the exhibitions at SFER IK are designed to interact with the dome’s curved interior structure. Trees protrude from the museum’s floor, where holes have been carved above and below to provide a steady supply of light and rain, and locally abundant and organic materials make up much of the interior structure. According to Paetzold, displaying art in this manner—and environment—makes everything “feel alive.” She continues: “Our senses are the most sophisticated tool, so to reinvolve them in the art is what’s really special.”

While many hotels started by hippies with design savvy and vivid dreams-turned-reality have failed under the new reign of hospitality’s grandeur, AZULIK’s evolving approach to architecture and design has kept the complex afloat. By relying less on rules and more on trial-and-error, the wheels keep turning, with no distinct end. As for the future, dozens of villas and a brand new temple are in the works. AZULIK may currently serve as one of Mexico’s most Instagram-worthy backdrops, but the entire complex warrants more than just a pause during your daily Instagram scroll.

You Might Also Like