New Exhibition Spotlights the Woman Behind the Schiaparelli Label

PARIS — Schiaparelli, the historic Paris couture house enjoying a revival under creative director Daniel Roseberry, wants you to know more about the woman who founded the brand almost a century ago.

The house, now owned by Italian entrepreneur Diego Della Valle, has partnered with the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris on an exhibition titled “Shocking! The surreal world of Elsa Schiaparelli,” the most significant retrospective dedicated to the Italian couturier in nearly two decades.

More from WWD

To illustrate her creative influence, the show features works by renowned artists who collaborated with Schiaparelli, including Salvador Dalí, Leonor Fini, Man Ray and Jean Cocteau, as well as outfits by the many designers she’s influenced, such as Azzedine Alaïa, Yves Saint Laurent, John Galliano and Roseberry himself.

To many visitors, Schiaparelli is best known as the brand that dressed Lady Gaga at the inauguration of U.S. President Joe Biden, Beyoncé on the night she set a record for most Grammys won by a singer, and Bella Hadid at last year’s Cannes Film Festival. The Lady Gaga and Bella Hadid dresses are featured in the exhibit, alongside a gold sequined jacket worn by Beyoncé for a shoot in British Vogue.

“It’s a rare case where a house is very well known for what’s happening today, and not what happened a century ago, at a time when a lot of houses are talking about events from 50 years ago in order to legitimize the fashion of today,” said Olivier Gabet, director of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

He noted that 46 percent of the museum’s visitors are under 26, so it made sense to reflect the house’s place in pop culture today. The challenge was how to communicate how modern the original designer was for her era.

Born into an aristocratic family, raised in the luxurious confines of Palazzo Corsini in Rome, and separated from her husband by the time she arrived in Paris from the U.S. in 1922, she was an artist, an entrepreneur and a single mother — a trajectory that Delphine Bellini, chief executive officer of Schiaparelli, believes will resonate with a broad audience.

“The story of Elsa Schiaparelli is really the story of a woman of today, who lived yesterday,” she said. “She was a woman of influence with a capital ‘i.’”

© RMN – Gestion droit d’auteur François Kollar, Charenton-le-Pont, Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie © Ministère de la Culture - Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / François Kollar

Founded in 1927, the business was shuttered in 1954 after accruing large debts. Since its relaunch by Della Valle in 2012, the house has spread the word about the history of its founder, starting with the publication of a book titled “Schiaparelli and the Artists,” published in 2017 to mark the 90th anniversary of the brand.

“For 60 years, the house lay dormant, so there was nobody left to burnish the legacy and tell this story,” Bellini said. “She was forgotten and it’s quite sad, because she’s extremely inspiring for the women of today.”

Gabet said the exhibition, due to open on Wednesday and run until Jan. 22, was part of a collective reappraisal of women artists who did not always receive due recognition during their lifetime. “Elsa Schiaparelli was a fashion designer who was considered an equal by the leading artists of her time,” he said.

“But Dalí and Man Ray don’t mention her in their memoirs, even though she mentions them in hers. Female creators were invisible, in a way, and she’s not the only one who was treated that way. It was the same for Meret Oppenheim and Leonor Fini. For a very long time, the history of art was very masculine,” he noted.

In a sign of change, Oppenheim will be the subject of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City next October, while a leading museum in Paris is said to be preparing a retrospective on Fini, who created the bottle for Schiaparelli’s signature fragrance Shocking.

A pioneer of the art collaborations rampant in fashion today, Schiaparelli was generous in sharing credit for her creations, as evidenced by a jacket in the exhibition that featured an embroidered face designed by Cocteau with the signature “Jean” prominently featured beneath.

“As a designer, she had a very different relationship to art that some of her contemporaries, like Jeanne Lanvin and Coco Chanel. They were survivors. They fought to get where they were,” Gabet said. “When you grow up in a Baroque palace, surrounded by Italian Renaissance and Classical Antiquity, intellectually, it’s reflected in the collections.”

Schiaparelli’s father was an academic specialized in the Islamic world and the Middle Ages, while her uncle was a renowned astronomer. “Her contemporaries were tapping artists to design their stores or create graphic design, but certainly not to be invited into the space of fashion design itself,” Gabet noted.

Marie-Sophie Carron de la Carrière, who curated the exhibition with Gabet, said Schiaparelli’s relationship with artists provided the gateway to her future clientele. She dressed Gala Dalí, who is shown in a photograph wearing her infamous shoe hat, and Nusch Éluard, the wife of poet Paul Éluard, one of the founders of the Surrealist movement.

A portrait by Pablo Picasso, featured in the exhibition, shows Nusch dressed in Schiaparelli, with jewels by Jean Schlumberger, who began his career at the house before gaining fame for his designs at Tiffany & Co. Alongside it hangs a jacket designed by Saint Laurent, inspired by the painting.

© Estate of George Platt Lynes/Courtesy of Musée des Arts Décoratifs

The exhibition is full of such cross-references. It shows how Schiaparelli and Dalí originated the newspaper print that later would inspire Galliano’s signature gazette motif. The Surrealist painter collaborated with Schiaparelli on her most famous dress, featuring a hand-painted lobster, famously worn by Wallis Simpson.

More intriguing still is the Tears Dress, displayed alongside Dalí’s 1936 painting “Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in Their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra.” Printed with a trompe-l’oeil motif, it creates the illusion of strips of flesh, prefiguring the punk movement by several decades.

Carron de la Carrière said the designer’s recurring use of pink, including her signature Shocking Pink, was steeped in the provocative images of Surrealist art. “Everything is based on the color of skin,” she said. “The lobster dress is also about female flesh, the female genital organ. It’s a celebration of a femininity that is both hidden and alluring.”

The exhibition highlights Schiaparelli’s pioneering mix of high and low references, via objects like perfume bottles shaped like a pipe, or a bottle of Champagne. Aside from her last fragrance, Zut, all her perfumes had names beginning with the letter “S.”

“We wanted to show what a visual merchandising mastermind she was, before that notion even existed,” Bellini said. “She was the queen of the concept.”

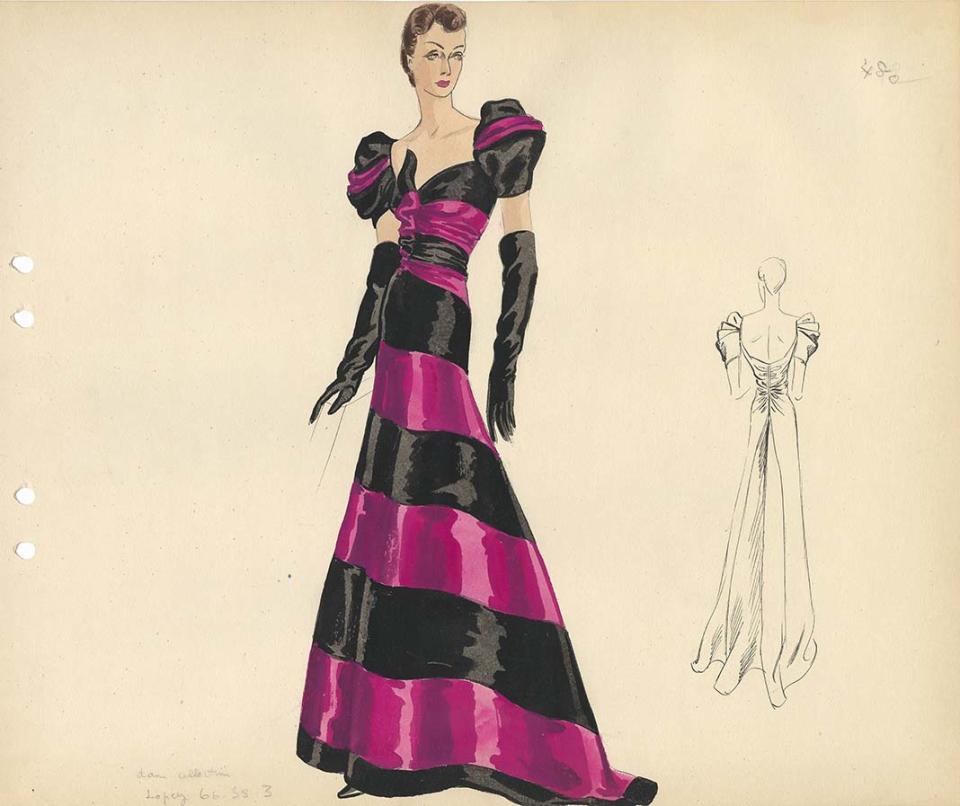

The large-scale show of Schiaparelli’s work is made possible by the fact that she donated her archives to the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the French Union of Costume Arts before she died. The latter collection, managed by the MAD, consists of 88 pieces of clothing and accessories, in addition to 6,387 drawings, some of which are on show for the first time.

Courtesy of Musée des Arts Décoratifs

With no clothing archive of its own, the house of Schiaparelli loaned Roseberry’s designs alongside elements of the original decor of its Place Vendôme salon designed by Jean-Michel Frank and Alberto Giacometti; drawings and collages by the likes of Marcel Vertès and Christian Bérard, and a host of photographs.

Gabet, who is overseeing his last exhibition at the museum before decamping to the Louvre, said the MAD’s fashion exhibitions compete against a plethora of high-quality shows in the French capital, and are aimed at attracting a diverse and demanding audience that goes beyond fashion aficionados.

“I sincerely think that when we show designs by Schiaparelli in the 1920s and 1930s, keeping everything in proportion, it’s the same thing as showing Michelangelo drawings in a big exhibition of classical art, because it’s fragile, it’s rare, you can’t loan it easily,” he said.

Bellini expects the exhibition to amplify conversation around Schiaparelli. “I think the halo effect is undeniable,” she said. “We hope it resonates across the world with a very large audience. That’s why we didn’t want the exhibition to be just about fashion, but also to have this big emphasis on artists and art.”

SEE ALSO:

Schiaparelli Comes Back to the Couture Runway With a New Look

A Year of Celebrities in Schiaparelli

Schiaparelli Designer Talks About Dressing Lady Gaga for the Inauguration

Launch Gallery: New Exhibition Spotlights the Woman Behind the Schiaparelli Label

Best of WWD

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.