It’s Time for Eternal-Girl Summer

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Last summer, I was completing edits on my first book—a thing that had, for years, existed as only a loose collection of drafts scattered across my desktop. These drafts were teeming with potential and could maybe even be perfect, so long as I could work on them forever (which I, contractually, could not). At the same time, I was weeks away from getting married, a famous marker of adulthood that would catapult me out of the paradise of perpetual becoming into a fixed state of being: wifedom! It wasn’t marriage that scared me; it was being a wife. Wives are serious. Wives are boring. Wives die—as in “My wife passed away five years ago” or “My wife, she fell down the stairs! Hurry!” I preferred being a girlfriend. Girlfriends have their whole lives ahead of them. Girlfriends get presents on their actual birthdays. Girlfriends write books that they will definitely, one day, let other people read … when they’re ready!

Instead of feeling the alleged joy that comes from good things happening to you, I was feeling a constant low-level dread and spending a lot of time looking up things like “Victoria Beckham kids how many” and watching Marianne Williamson YouTube clips on how to become a spiritual beacon. I was standing (okay, lying down) on the precipice of what Jungian psychology refers to as “threshold experiences”: the archetype of new beginnings, an initiation into a new phase of existence where the old self must die to be reborn. Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz identifies this resistance in her book called Puer Aeternus, Latin for “eternal boy,” better known as Peter Pan Syndrome, the pathological arrested development that plagues some men well into old age. The book only briefly mentions his female counterpart, the puella aeterna, but upon reading about her, I felt a small pang of recognition. It me! I had spent so many years psychoanalyzing Peter Pans/ex-boyfriends who referred to yearlong relationships as “hanging out” that I had failed to recognize my own puella nature.

I went in search of more information, but the puella literature online is surprisingly limited; all I could find was a Reddit thread and a handful of academic PDFs. Meanwhile, Peter Pan got an entire Disney franchise and his very own cool slang term, fuccboi. Our closest equivalent was the manic pixie dream girl, who entered our cultural imagination in the early aughts with characters like Summer in 500 Days of Summer and Clementine in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. They personified the male fantasy of the eternal girl: always free-spirited, whimsical women with cutesy names and weird haircuts. But these portrayals failed to recognize the full humanity of the puella, flattening her into a trope: an eccentric, noncommittal love interest who seemingly existed only to ruin the male protagonist’s life.

A true puella refuses such categorization, believing herself to be too special for that. She is a paradox, unknowable even to herself. She prefers to remain elusive, desiring to be seen but not to be known intimately. She performs confidence to compensate for an inner emptiness and lives in a fantasy of her own making, believing that her real life is always just about to begin. She feels disconnected from her body and especially fears being reduced to her earthbound, corporeal form through childbirth and motherhood: the ultimate puella death.

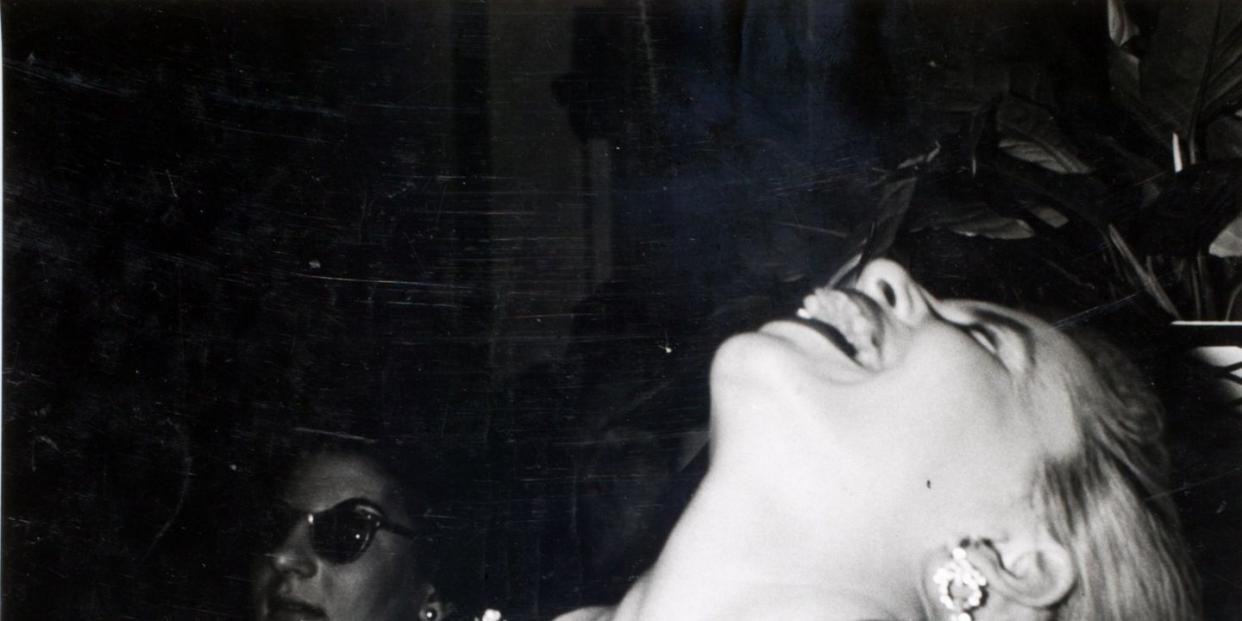

She’s an Eve Babitz in a world of Joan Didions. She’s the goddess Artemis roaming the forest with her squad of nymphs. She’s also every character in my book, Bad Thoughts, a satirical story collection about modern women, mostly artists or aspiring artists who are unwilling or afraid to advance to the next stage of life. Instead, they stagnate in place, act out, overthink, seek spiritual ascension through drugs, or give up entirely. They spend too much time online, while their future happens elsewhere or never arrives.

It never occurred to me to use an archetype as an organizing principle for my book, but once I made the connection, I couldn’t unsee it. It gave me a new framework for understanding my characters—and myself. I wrote many of the stories while feeling a restlessness and ennui that I largely attributed to L.A. smog and my all-microwave diet. There was something romantic about living alone in my tiny apartment, writing in bed until my wrists ached. I’d made a home for myself in the waiting room of life, watching a block of sun move across the floor like a perpetual summer afternoon. I was in no rush to “grow up.” A lot of my friends were also feeling this way. We all shared a uniquely modern predicament: namely, being one of the first generations of women to enjoy unprecedented levels of freedom for the first time in all of human history. (God, I hope this super-reductive statement ages well. Oh, it already hasn’t? Okay.) Compared with all of human history, it’s been like 12 minutes. So, yeah, maybe we were still finding our footing in this new paradigm. Maybe, on a subconscious level, we felt entitled to languish in an adolescent fugue state and waste time contemplating our seemingly infinite life choices, as men have done for eons!

The puella archetype dates back to Greek mythology, but she’s never felt more relevant than now. We’re more online than ever, between work, maintaining social connections, streaming TV, and Zoom therapy. The more tethered we are to the digital realm, the more our sense of time warps and the outside world feels less real. This really hit me the other day when I used my finger to scroll a piece of paper. Our increasingly atomized lives means less interactions with older generations and therefore fewer models for moving through thresholds. My mom was 23 when she had me, and now whenever I see a 30-year-old with a baby, I think, “Wow, a teen mom.” Not to mention our cultural obsession with preserving youth at all costs, which frames aging as a failure, or existential threats like climate change, which really mess with our capacity to imagine a future.

The puella isn’t just a symptom of neoliberalism; the roots of her psychic wound can be traced back to childhood, with her dad. From a Jungian perspective, the puella child internalizes her negative or absent father figure (usually a puer aeternus himself) by creating a dominant animus, the unconscious masculine, which cuts off her access to her inner feminine. When I think about my own childhood, I grew up around a lot of hypermasculinity and interpreted that as a form of power. I adopted these traits as a survival skill and taught myself to become disciplined, quick-witted, and confident; I perceived my emotions as inconvenient or unsafe. In a patriarchal culture, my confidence was encouraged and rewarded, but this kept me estranged from another untapped source of power: my vulnerability.

In many ways, writing has become an exercise in microdosing thresholds to build up my tolerance. The ideal of the perfect draft has to die in order for you to finish anything. Even writing this essay was a struggle; I stopped halfway and literally opened an online T-shirt store just to avoid finishing it. I come to you now as a recovering puella, as evidenced by the fact that my essay is here and I’m now officially a W-I-F-E! Healing my inner puella will probably be a lifelong project for me. But it’s less about denying the parts of myself that helped me survive and more about stepping out of the waiting room of life and trusting myself enough to surrender into the unknown, again and again and again.

You Might Also Like