Eric Bogosian Is as Good as New York Gets

Eric Bogosian had written and acted in a number of the one-man shows for which he was becoming increasingly famous when he tried to pull rank on Robert Altman, only one of the most important directors in film history. It was 1987 or so. Bogosian had been cast in The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, a TV movie, and thought he’d help the director out. “My first day on set with Altman, I said, ‘I have a good side and a bad side,’” he says.

Robert Altman was unmoved. “He said, ‘Oh, really? Which side is your bad side?’ He only shot from that side for the rest of the thing. I don't even know what I was fucking talking about, good side, bad side. I was so new to the whole frigging thing,” Bogosian says, bashfully.

More than 30 years later, Bogosian had accumulated the capital—over a career spanning theater, film, television, and publishing—to make a more successful request. He’d been sent the script for Uncut Gems, the Jewish fever dream from the Safdie brothers. After lobbying phone calls from pal Natasha Lyonne and co-director Josh Safdie, along with a screening of the Safdies’ previous film Good Time, he was intrigued, though not without reservation.

Bogosian was up for the part of Arno, the brother-in-law foolish enough to lend a hundred grand to Sandler’s gambling-addicted Howard Ratner, and vengeful enough to employ a couple of pipe-hitters to claw it back. Arno spends the final act of the film stuck, along with his two heavies, between the double-locked “mantrap” doors in Ratner’s Diamond District shop. In the finished film, it’s a teeth-grinding piece of cinema, Arno settling in and lighting up a cigarette while he waits for Howard’s climactic bet to pay off. Reading the screenplay, Bogosian was concerned.

“I saw that script,” he says, “and I'm like, Yeah, you're going to keep me in a plastic box. And how long is that going to go for? Because I just didn't imagine being in there with two guys I don't know, and Adam's outside going, ‘What's my motivation?’” (He’s quick to clarify that “it wasn't like that at all. I mean, he was absolutely so much fun to watch from inside.”)

So he hit on a novel solution. “I told my manager to tell them that I was claustrophobic, and that I could never be in there for longer than a half hour at a time.” It worked: what Altman had scoffed at, the Safdies were willing to accommodate.

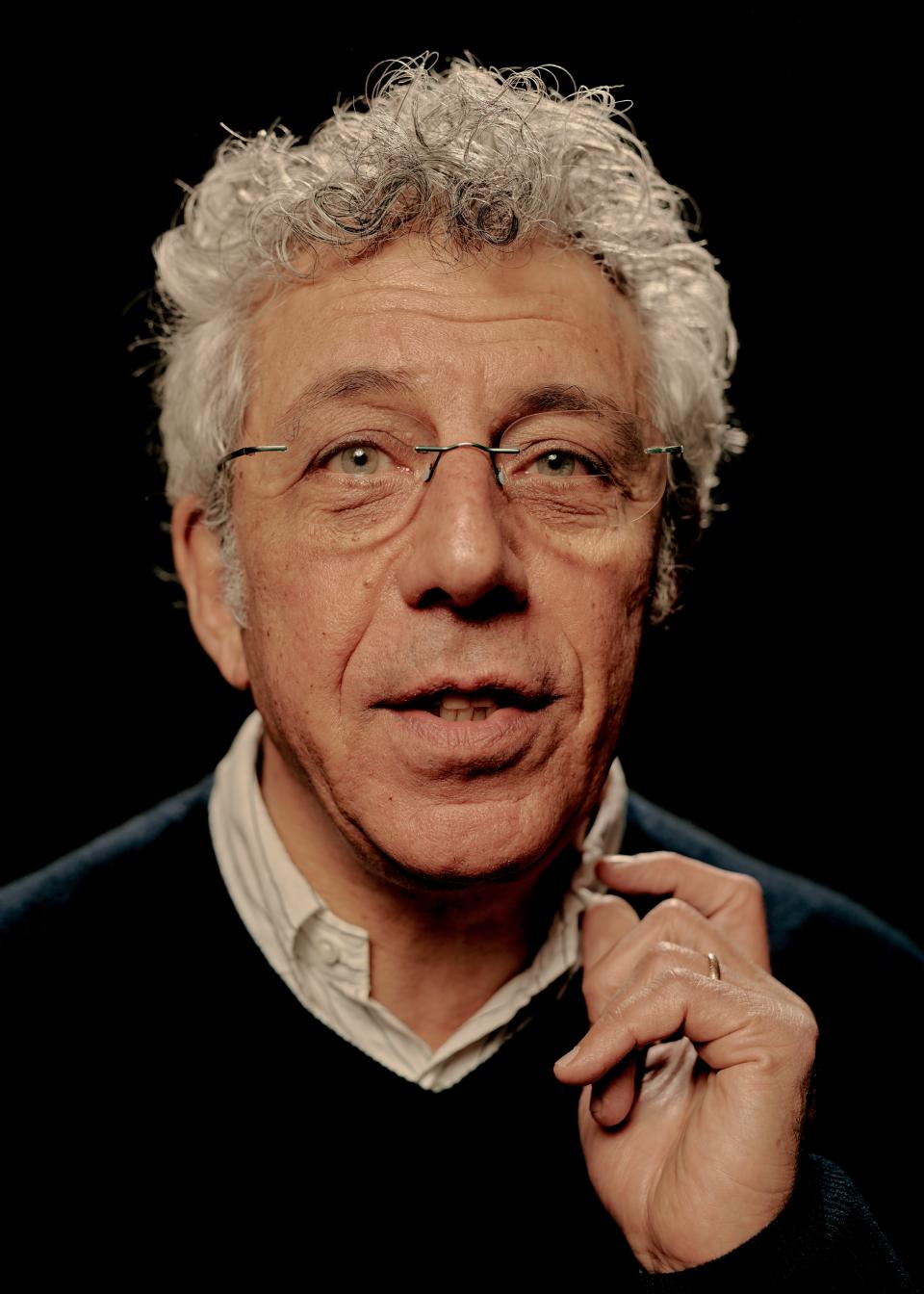

Because while in 1987 Bogosian was an upstart, a punk with roots deeper into the downtown art scene than the theater, he has since joined a kind of New York royalty. We’re in Bogosian’s office, a small apartment downstairs from the one he shares with his wife, the theater director Jo Bonney, in Tribeca. He’s having his photo taken—both sides, this time. He’s got a head of silvery ringlets, rimless glasses, and a honeyed, nasal voice so regionally specific you can probably chart it to a single downtown Manhattan block.

He has not really stopped working in those three decades, shifting from early, aggressive theater work into Hollywood screenwriting, and then to writing novels and a work of nonfiction about the Armenian genocide, then into a steady gig as a cop on Law and Order. But over the past few years, Bogosian has returned to acting with a series of scene-owning supporting turns, typically as the kind of guy who has opinions about both your investment strategy and your order at Katz’s. (Bogosian, 66, is Armenian, but recently explained that nearly every one of his later-period roles—save for Arno—is as a Jew.) First was Lawrence Boyd, the slippery banker on Showtime’s high-octane finance drama Billions. Then Gil Eavis, the hilariously dead-on Bernie Sanders stand-in on HBO’s Succession. And then, finally, Arno in Uncut Gems. Sandler is that film’s alpha and omega, its reason for being. But Bogosian helps bind the thing together. He is the one who gets to accuse Howie of resurfacing his fucking swimming pool.

These days, the old solo artist doesn’t mind a little recognition. “Now, in the case of me playing these guys, people are telling me that I'm really good or great in these roles and I can tell the difference between people kind of saying that and when they mean it. And I'm of course very happy about that.”

Bogosian moved to New York from Boston in the ‘70s, and fell in with a group of artists—the photographers Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo, most notably. Sherman, who served as her own heavily costumed subject, was “probably the perfect embodiment of what we were thinking about then, which was that these archetypes live in us—and it's not pop art, it's not cliche, it's not camp.” That line of thinking applied itself perfectly to the theatrical work he was exploring. “I created these galleries of guys,” he says: a man reflecting on his enormous penis, a smarmy doctor, an overweening Hollywood type. He’d collect the guys in stage shows, group a dozen of them together and run through them like sweaty, beery lightning.

Bogosian’s guys are rude, louche, abject, off-color, almost defiantly unlikeable. It strikes me that he was interrogating and disassembling what we now call “toxic masculinity” decades before the term existed; it is almost impossible to imagine a contemporary celebrity becoming famous, which Bogosian did, pursuing the same line of work. The shows were funny, but the material was not light. “Playing these roles was definitely an exorcism for me,” Bogosian says, turning to another notable Tribeca resident by way of explanation. “De Niro didn't give a lot of interviews, and I would hang on any and every word he said. And he said, ‘I get to play these guys without the consequences.’” And that was it. “It’s the fantasy of I want to be that guy. I want to be the guy who beats me up.”

He picked up an agent, kept growing in popularity, lost a few years to what his dealer described as heroin, “but not like the heroin the junkies do.” After he got sober, he says, “Everything just switched gears so rapidly that it took my breath away. For the next few years, it was like dominoes hitting each other. I could do no wrong.” The biggest domino was Talk Radio, a play Bogosian wrote to accommodate a guy he’d been workshopping who demanded more than the solo-monologue treatment. Bogosian’s Barry Champlain is an early radio shock jock, a budding Imus or Stern, who seems to loathe his listeners and himself in equal measure. “When I found this character who was a talk jock, I just felt, This guy's too good. This guy has the possibility to be a kaleidoscope of many things that will allow me to go exploring in my own self. I knew I loved playing Barry, and I wanted to be Barry for longer than a four-minute bit.”

“I think that the history of humanity is the history of technology,” Bogosian says. “We're basically always really the same bloodthirsty, horrible people to each other, but we get different ways to do it with each other.”

The play was a finalist for the Pulitzer in 1987, and Bogosian worked with Oliver Stone to turn it into a movie the following year. It is scarily prescient, with waves of racism, anti-semitism, and pure American hate soaking Barry’s nightly interactions with his listeners. It’s resonant in 2020 for the obvious reason—“We now have this man who has an incredible sense of what works and doesn't work in front of an audience as our president”—but it is less about a specific moment in talk-radio history than the way people have always found novel ways to be dicks to each other.

“I think that the history of humanity is the history of technology,” Bogosian says. “We're basically always really the same bloodthirsty, horrible people to each other, but we get different ways to do it with each other. And we're in a period of intense change right now.” This, I point out, is awfully close to Champlain’s riveting monologue at the end of Talk Radio. Bogosian smiles. “I just keep saying the same things over and over again. I’m never going to stop saying these things.”

In Bogosian’s telling, the New York theater scene and Law and Order are intimately connected, two moons locked in orbit. In 2006, he landed a gig as Captain Danny Ross, doing some 60 episodes of Criminal Intent. (“My role was to walk in with a coffee cup and review the exposition,” he says.) Series creator Dick Wolf, Bogosian paraphrases, called Law and Order a writer’s show. “Which,” he concedes, “to some degree it is. But the thing that Dick and his cohorts knew was that New York was filled with all these great character actors, and the lowliest role on the show would be played by somebody who's brilliant at counteracting and giving you this little nuance.”

Bogosian credits Law and Order with getting him comfortable with acting for a camera, and his theatrical peers with elevating his craft. “This is not the way it was in 1985,” he says. “In 1985, everybody's coked out and kind of just”—he blows a raspberry—“laying up. But now we've got all these craftsmen.” He credits the shift to Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s deep investment in their world: “It can't just be him, but Phil Hoffman was a saint in the Church of Let's Be Serious,” Bogosian explains. “Because prior to Phil really entering in a big way, young men who started to make it in this business would basically migrate to LA, start living the life, and get a lot of blowjobs.” Hoffman directed him once—he played Satan opposite Sam Rockwell’s Judas—and the experience left a mark. And not just on him. Now, Bogosian sees what he calls "serious actors" all around: “Adam Driver, Michael Shannon, Michael Stuhlbarg, Marin Ireland, Jessica Hecht.”

And now, serious actors with unique and craggy faces are no longer confined to Law and Order. Thanks to the streaming boom, Bogosian says, studios have “discovered they don't necessarily have to have a person in the lead that anybody's ever heard of before. And as a result, there's all these actors who are flourishing.” He cites his Succession castmates Sarah Snook and Brian Cox as examples, but he might as well be talking about himself.

But the shift is not without cost. Television means more good work emerges, but it can’t deliver the same charge that theater does. One elbows the other out. “Theater costs so much fucking money,” Bogosian says. “I saw a play—a very, very, off-off-Broadway play—the other day. It was absolutely terrific. And it was $120 a ticket.” As a result, “the community cannot go and see each other's stuff. They can't afford it. I mean, even well-known actors who do very well, they can't afford it.”

In his 40-odd years here, Bogosian’s Manhattan—of the Mudd Club and Tier 3, of off-off-Broadway and cheap artists’ lofts—has become overrun with Chase branches and 7/11s. Something equivalent, it seems, has happened to the city’s arts and artists. It’s a strange irony: the streaming deluge means an expert character actor like Bogosian can transmute his sharp-elbowed, scene-elevating downtown sensibility to far larger audiences than he did as a one-man operation. But it also makes it that much more unlikely that the New York theater scene will produce another Bogosian.

But then Bogosian tells me a story that underscores the strange interplay of art, commerce, and luck in the creation of a career, and I’m reminded that it has always felt like this: that the craft and the business have always shaped each other. In the ‘90s, Bogosian turned Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll into a kind of concert film. At the time, HBO, which had an option on his next project, let him take it to a different company, shifting its option to his next production. “Had I appeared on HBO at that time,” Bogosian says, “my life would've been completely different. Instead, the movie was made by Avenue Pictures, who went out of business the day that they released the film. The film went immediately into receivership, bombed at the box office, and didn't exist on DVD forever.”

And then another, simultaneous catastrophe. A record label was set to issue a CD version of the show, but “when they found out there was a movie being made, the movie company and the record company butted heads. I was told by my lawyer I had to choose which one I would side with. I didn't know the movie company was going to go out of business.” He sided with the movie company. As a result, the label—SBK—promptly destroyed the 30,000 CDs it had produced.

Here is where it gets good, where the casual viewer is reminded that acting is not a job for the faint of heart, that attempts to win will be laughed at, that moments of abject humility sometimes lead to small joys. Because one of SBK’s founders, Charlie Koppelman, had a son, Brian, who served as a kind of informal A&R for the company. Brian had been at Tufts when Tracy Chapman was there, saw her perform, and encouraged his father to sign her to a deal. Brian had also gotten wind of a downtown punk making waves in the theater world, and brought his father to see a young Eric Bogosian—leading to a deal, and then to the junking of 30,000 CDs.

Years later, Bogosian says he wound up in a poker game with the younger Koppelman. (Bogosian is an avid player.) “I said, ‘Koppelman: that name is really familiar.’ He goes ‘Yeah, Charlie Koppelman. I'm his son. I brought him to your show 19 fucking million years ago.’” They got to talking. Koppelman had become a screenwriter, was putting together a new show at Showtime. It was all coming back around. New York still retains some of that magic.

“He's like, ‘I'm going to be doing this TV show, Billions,’” Bogosian says. “‘Maybe you want to do it?’"

Nicholas Braun, Succession’s endlessly amusing Cousin Greg, takes GQ for a cruise around Coney Island.

Originally Appeared on GQ