Vogue Got an Exclusive Tour of Chanel’s Ateliers While Tonight’s Métiers d’Art Collection Was Being Made

Chanel Metiers d’Art Behind-The-Scenes Pre-Fall 2019

As the models of Chanel’s Métiers d’Art show filed around the Temple of Dendur attired in looks encoded with colorful graphic symbols, their silhouettes radiating glints of gold from all angles, it was clear that this was no ordinary ode to Egypt.

Such a cool, contemporary display of splendor could only have been dreamed up and executed by Karl Lagerfeld and the maison’s masterful ateliers. From scarab beetles to Ettore Sottsass; Memphis the ancient city to Memphis the design movement; hieroglyphs to graffiti; camellias to lotus flowers—all these cleverly related references were scattered across intricate embroideries on jackets, leather paneling, plissé soleil (literally, “sun-pleated”) skirts, belt buckles, jewelry, and heels encrusted with pearls. The gods are in the details, indeed.

After the 2017 show in Hamburg, where Lagerfeld grew up, finding a destination that would offer meaningful inspiration must have been a challenge. But the Metropolitan Museum of Art proved a fitting backdrop for someone who recently commented that “nothing is more modern than antiquity.” Whether personal, historical, or cultural, Lagerfeld’s exploration of the past inevitably yields fertile ideas for these collections. And year after year, the artisans that occupy the workshops continue to translate each point of departure with creativity and savoir faire.

Lagerfeld began the Métiers d’Art concept in 2002 as a way to recognize the efforts of the ateliers acquired by Chanel through its Paraffection subsidiary. When founded in 1997, Paraffection had already acquired three artisanal maisons, starting with Desrues, their longtime button supplier, in 1985. Today, there are 26 maisons representing every conceivable fashion expertise, including gloves (Causse), millinery (Maison Michel), goldsmiths (Goossens), and cashmere (Barrie). Paraffection is an elision of par affection, or “with love,” and it’s clear this applies as much to the preservation of such rarefied know-how as to the workmanship itself. But the support also comes with commercial objectives, as several of the ateliers have an expanded retail presence independent of their contributions to Chanel. Earlier this year, construction began on a site in the Parisian suburb of Aubervilliers that, at nearly 275,000 square feet, will be large enough to house the entire Paraffection family. Designed by award-winning architect Rudy Ricciotti, the buildings will feature a striated concrete casing inspired by woven fabric.

In the meantime, many of the ateliers are divided between two main complexes, one that is also in Aubervilliers, the other in Pantin—both roughly a half-hour drive from Chanel’s famous address of Rue Cambon. Exactly two weeks ago, with most of the collection in various stages of production, photographer Alice Gao and I were guided through four of the ateliers where we observed how much handcraft goes into the embroidery of Adesuwa’s blush pink dress or the construction of Pharrell’s lustrous gold boots.

At the heart of Maison Lesage is an archive room where upwards of 75,000 samples are catalogued in wooden drawers that resemble library filing cabinets. In 1924, Marie-Louise and Albert Lesage took over the Michonet embroidery maison that had been in existence since 1858 and the beautifully stitched specimens date back that far. Until his death in 2011, their son François Lesage spent decades fostering collaborations with all the big fashion houses in Paris, most notably Yves Saint Laurent. Elsa Schiaparelli had also been a client and in light of the rivalry with Gabrielle Chanel, it wasn’t until Lagerfeld’s arrival in 1983 that the Lesage began contributing the embroidery and tweeds that are now so fundamental to the Métiers d’Art show (the tweeds are woven in the South of France by Act 3, a specialty workshop that belongs to the maison).

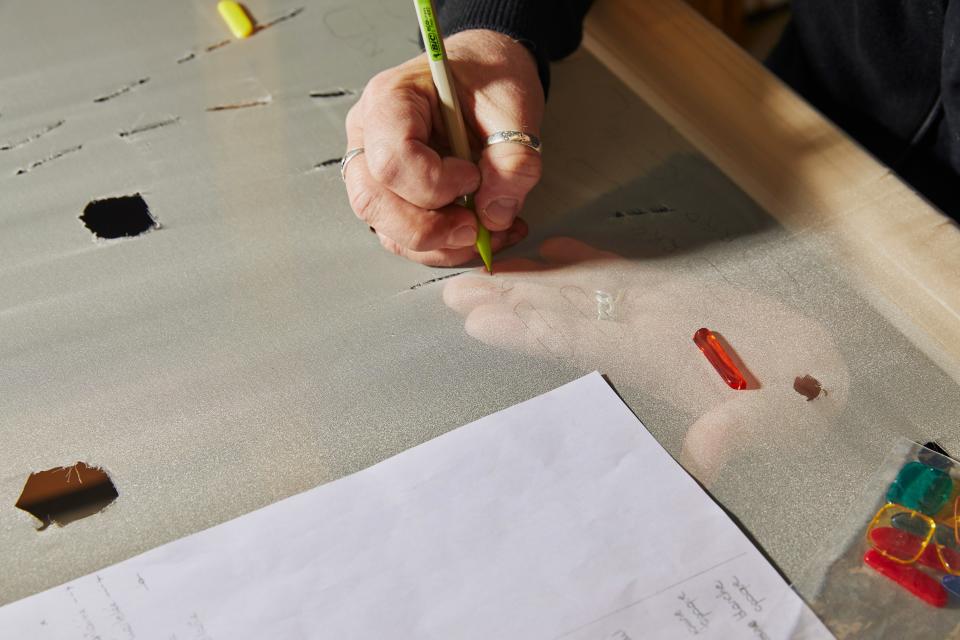

Hubert Barrère, a longtime embroidery expert, has been artistic director of Maison Lesage since 2011. On his desk in Pantin are a row of Chanel nail lacquers (“the most perfect product design”), a tray of slender crayons which he uses to sketch designs, and a stack of books on Ettore Sottsass. (Fun fact: Lagerfeld was once an avid collector of Memphis furniture, which he kept at his former apartment in Monaco.) After receiving sketches from Lagerfeld—many of these are tacked to his wall and I do my best not to stare—he and Virginie Viard, Chanel’s fashion studio director, will usually engage in a free association of references that ultimately inform the embroidery. “Virginie is very in tune with his creativity,” Barrère says, while tracing over one of his designs with a pencil. “Here, we have a liberty of interpretation and what is important is that Chanel says yes or no . . . . We have all known each other for many years, we can anticipate what Karl wants. And moreover, we just want to make him happy.”

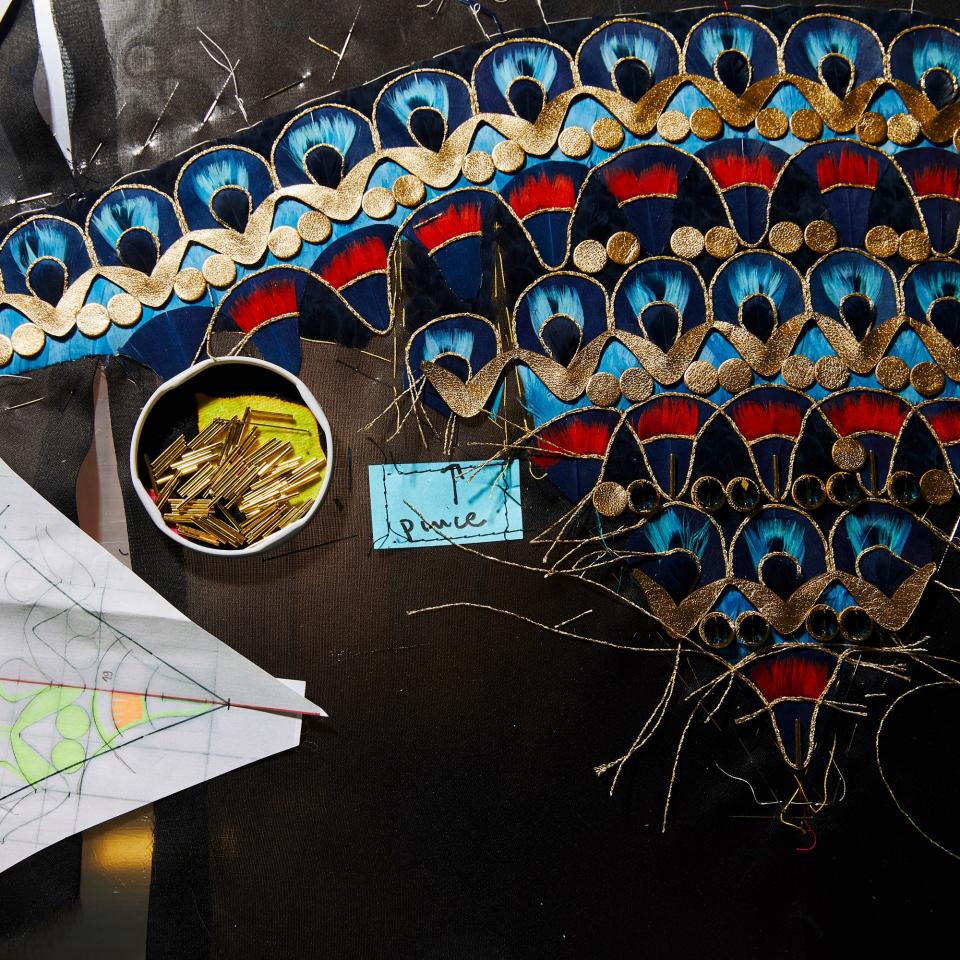

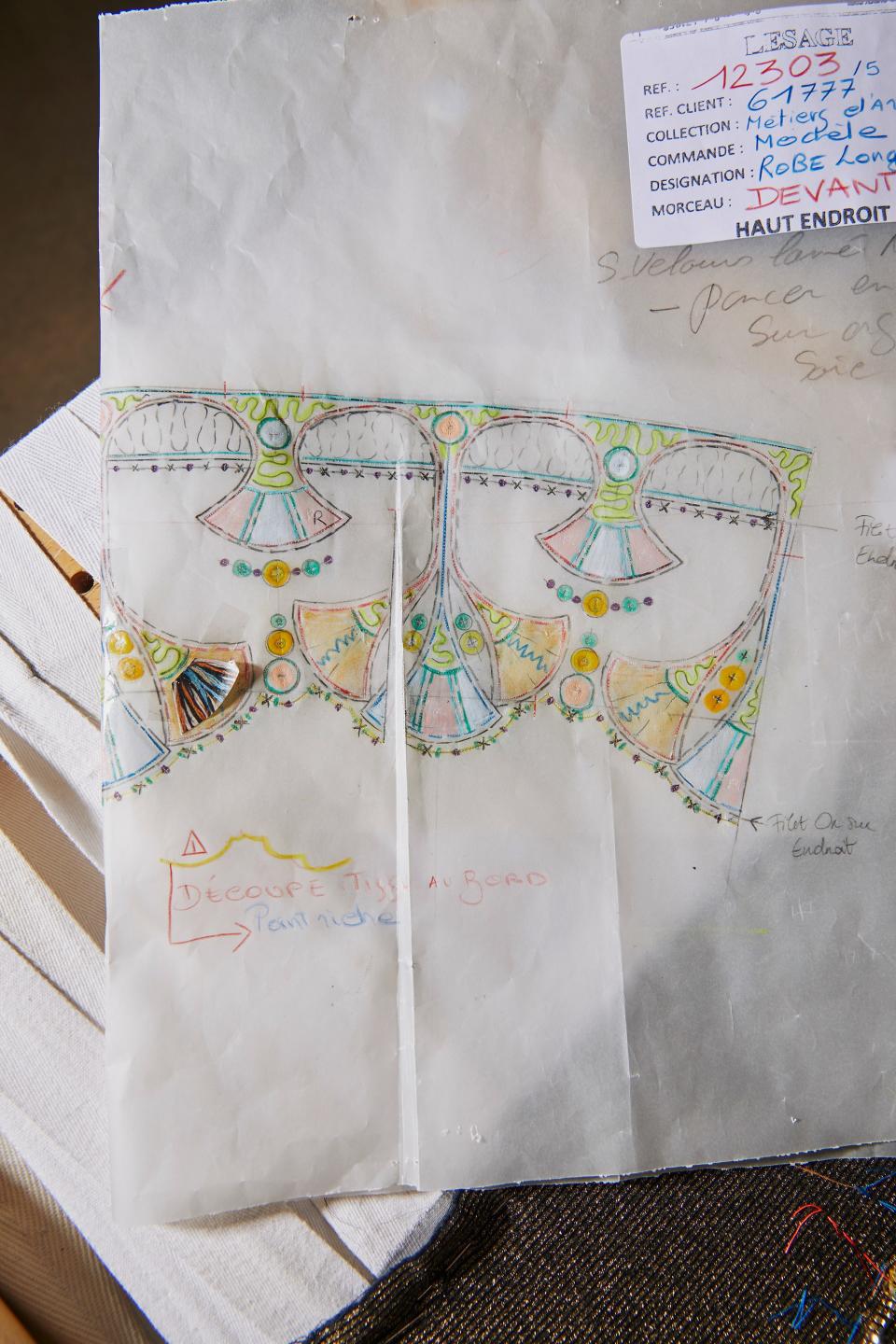

One floor up in the workshop, a group of women—roughly 80 percent of the embroiderers are female—have been spending days doing exactly that. I’m simplifying the process somewhat, but essentially, they use tracing paper, a punching machine, and a felt pad powdered in chalk to make an impression on the fabric, which is supplied by Chanel. Then, with their needle and a variety of threads, strass, and beading, they follow a well annotated drawing stitch by stitch, most often using the Lunéville technique (apparently, it is the fastest but most complicated to learn). One of the artisans, Caroline, is realizing a tassel-like pattern interspersed with pastel stones and fine gold chain. She has already spent 17 hours on just a small portion of the front.

It seems hard to believe that the atelier is only afforded three weeks to complete all the embroideries for the Métiers d’Art show. Nonetheless, Barrère points out that spending this amount of time on the pieces is partly what makes a luxury. “Time is money—and if you have 50 or 100 hours minimum of embroidery, the price is colossal. But Chanel will do this. And it is received well and it sells well,” he says. “If Chanel had not involved itself in the métiers d’art by purchasing them, today, there would likely no longer be any métiers d’art.”

With this statement fresh in my mind, the visit continues at Lemarié, where general manager Nadine Dufat qualifies that having expertise in feathers means more than assembling a fluffy ostrich jacket or marabou skirt. In this evening’s show, for instance, what might have looked like a printed interpretation of Egyptian tomb paintings was actually highly detailed feather marquetry—like inlaid puzzle pieces. Feathers obviously don’t come in such a brilliant shade of lapis lazuli; Dufat notes they absorb dyes particularly well.

Founded in 1880, the atelier is among those with which Gabrielle Chanel worked directly, for in addition to feathers, Lemarié’s other speciality is molded flowers—i.e., the iconic camellias. Dufat extends a drawer to display a plethora of specimens with their perfectly sculpted petals (classically, 16 per flower though there can be as few as 12 or upwards of 20). Each one results from tools that cut and heat an array of materials. For this collection, the artisans assembled micro-size flowers in raw-edged denim and gold leather that are bordered in beads. “It’s a very specific know-how,” she says. Lemarié’s artistic director is Christelle Kocher of Koché, who brings a sense of youthful, Parisian edge to the traditional workmanship, which also includes couture embellishments of textiles, from geometric origami folds to frilly ruffles. Here, too, time is the challenge; one dress could easily require 100 hours of manual labor. “The problem is to do that within a week,” she says. “In two weeks, we have to do everything.”

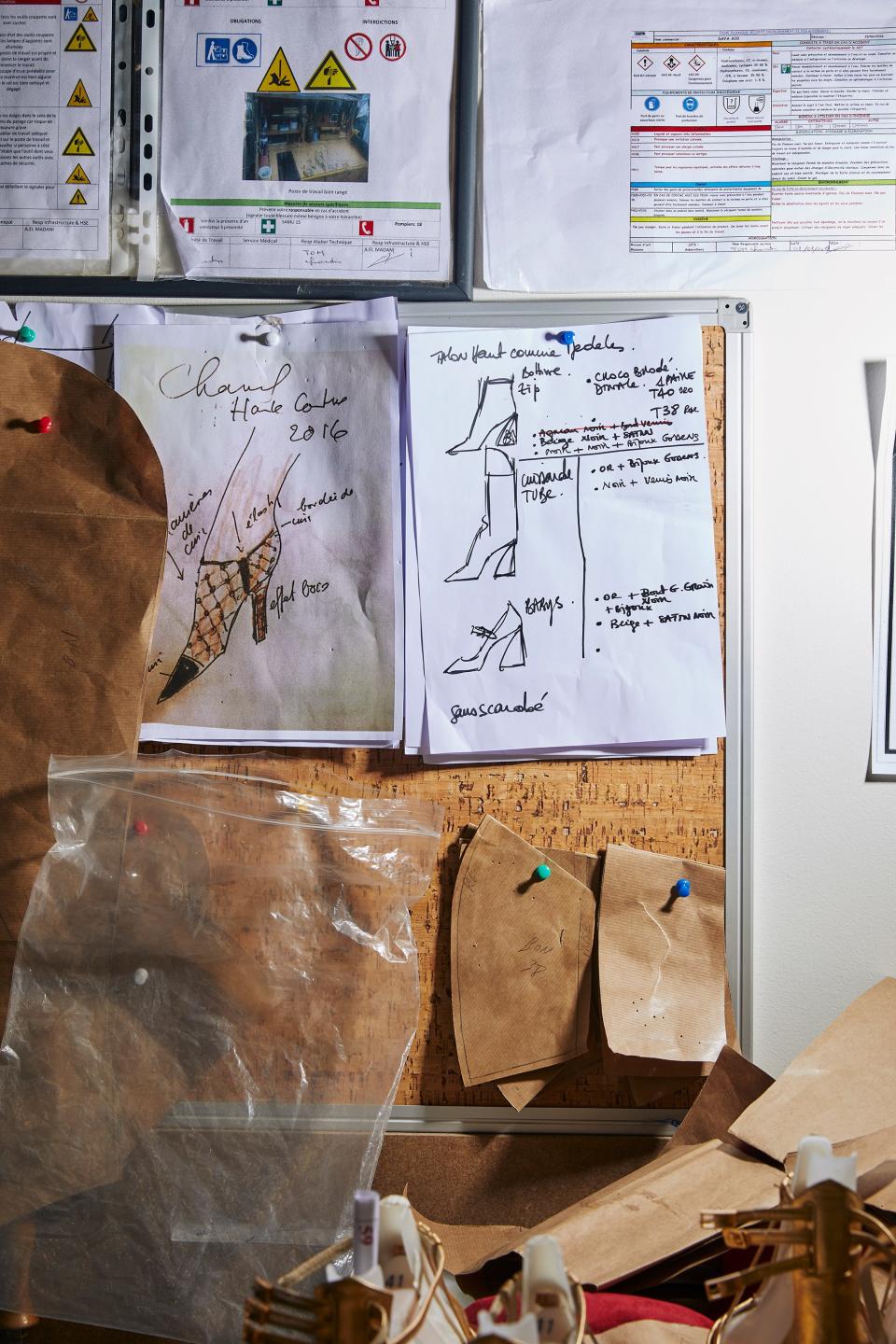

Over at Massaro, one of the ateliers located at the Aubervilliers site in an old matches factory, production is definitely in full swing. Here, the nose inhales whiffs of leather, wood, and polish, while the regular pounding of hammers serves as an audio accompaniment. Each artisan has his or her own work station replete with tools that have likely changed little since the bespoke shoemaker opened for business in 1894. In 1957, Massaro’s collaboration with Gabrielle Chanel resulted in the signature two-tone beige and black sandal with its civilized six-centimeter heel. Over the decades, the workshop has built up an impressive list of private clients, as well. The archive numbers some 45,000 lasts, all suspended in rows from floor to ceiling along a mobile shelving system. Artistic director Jean-Etienne Prach happens to choose an aisle where we spot shoe molds created for Oprah Winfrey, Keira Knightley, and André Leon Talley, plus a pair of ridiculously vertiginous platforms. You probably could have guessed: Lady Gaga. They make the Chanel shoes look conservative by comparison.

But in fact, Prach notes that Lagerfeld rarely diverges from a certain 1930s-inspired silhouette with a quasi-square toe (one obvious outlier: the haute couture sneakers from 2014, also produced by Massaro). In the weeks leading up to the Chanel shows, most personal orders get sidelined and all hands are on deck— including two otherwise-retired cobblers and a young apprentice. One member of the team is midway through Pharrell’s boots—he estimates this is a 60-hour job from start to finish—while others are completing approximately two dozen pairs of women’s sandals that boast golden lines extending along the feet. Prach also treats us to a sneak peek of black boots tagged with gold graffiti drawn by artist Cyril Kongo and shows off a heel that has been studded with stones and metalwork executed by Desrues and Goossens. “We’re one big team working for Mr. Lagerfeld,” he says, betraying a certain amount of pride. The fact that Lagerfeld’s own boots are Massaro is the ultimate vote of confidence.

The final stop is Lognon, the pleating atelier that exists within the Lemarié maison. Here, the space is a veritable delight of unfamiliar forms. Hundreds of cardboard molds have been rolled up so that they resemble textured vessels whose purpose is unclear. Laid out flat, however, they become the template for transforming a flat piece of fabric into something with accordion dimensions. Claire Manceau, who is responsible for the operations, takes out one of the molds—incidentally, called a métier—and demonstrates how to properly place a large scrap of silk between the two cardboard panels, before scrunching them together and binding them tight. This roll joins others in a steam furnace where it cooks for a few hours. Then, right before the team of six leaves for the day, the furnace is emptied and the rolls are left to cool overnight. The next morning, the cardboard is unfurled and the fabric has retained its freshly pleated shape. Whether diaphanous mousseline or leather, the process is the same. Manceau says that while it’s hard to articulate, there is a “style Chanel” to the pleats they execute. “It’s their identity,” she says.

This calls to mind something that Hubert Barrère from Lesage said earlier in the visit. “Embroidery is like a language; there are letters, words, sentences. The point of departure is always the needle and the thread. And just with that, you can compose an extraordinary score—an entire book, you might say.”

By contrast, the nod to ancient Egypt reminds us that, while we communicate universally in emojis, we are illiterate in hieroglyphs (scholars notwithstanding). All we see are enigmatic graphics and beautiful ornamentation. Beyond the dreamlike destination aspect of the annual show, Métiers d’Art is a valuable exercise in deciphering and perpetuating workmanship as a language. Little do we realize that with every collection, we become more and more fluent in Chanel.