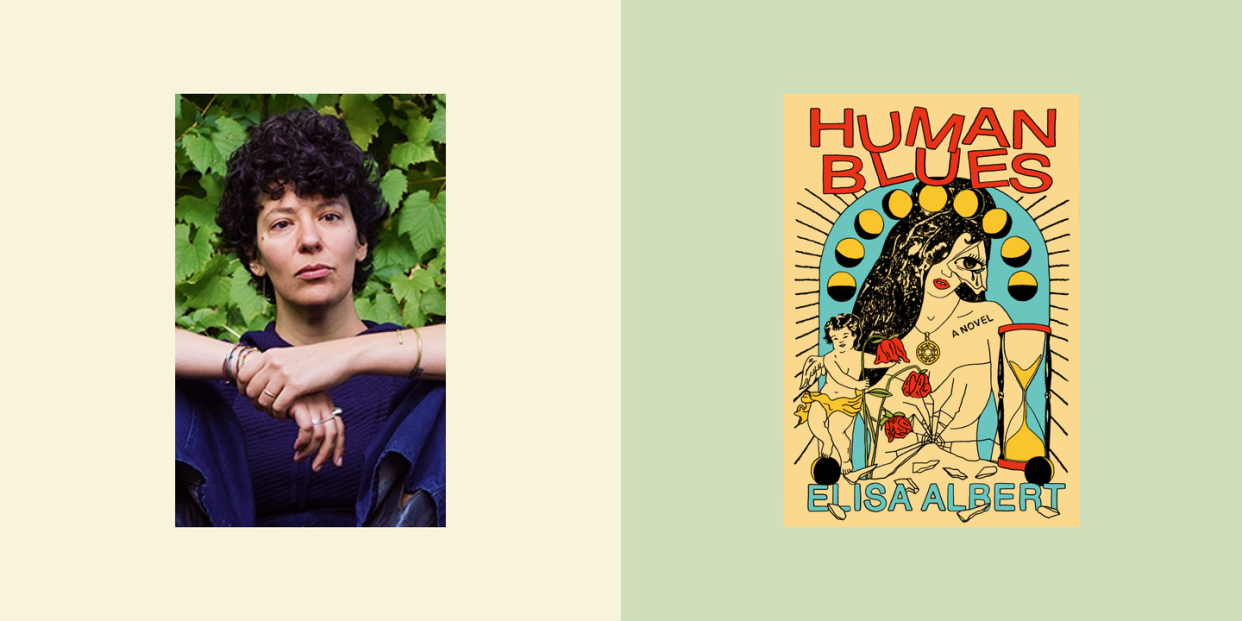

Elisa Albert’s “Human Blues” Is a Crackling and Bighearted Novel

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Motherhood is an awe-inspiring rite of passage in which no two experiences are alike. Few writers have captured its radical challenges better than the novelist Elisa Albert. Her expansive novel Human Blues follows nine menstrual cycles in the life of Aviva Rosner, an iconoclastic singer-songwriter (think Ani DiFranco in her prime rather than Brandi Carlile) in her late 30s. Through this ingenious literary structure, Aviva’s hopes and frustrations both ebb and flow over the course of the novel. She’s been trying for three years, without any medical intervention, to have a baby. No luck. Her kind husband, an Albany high school teacher, is patient and understanding, but Aviva is hitting a wall. Something has to give.

It’s at this point that Aviva is poised to launch a solo tour (just her voice and guitar) for her fourth album, Womb Service, a cheeky tribute to a woman’s “getting to know her body, welcoming the age of embodied womanhood in its prime, leaving the past behind once and for all…creation, nurturance, stability, balance.” Aviva’s gnawing ache to be a mother looms over her tour dates, creating tension with others who tell her to simply “hurry up,” see a specialist, or just take fertility drugs already. Facing another cycle without pregnancy, Aviva considers, “There was no going back; only forward. Rites must be had! If not the rite of pregnancy and birth, well. We don’t always get to choose our passages.… We can only go through doors that are open to us.” Whether it’s parenthood, art, or both, what Aviva is searching for is a sense of belonging.

This equipoise is hard fought—yet she isn’t entirely willing to give up hope that pregnancy will come on its own accord. Aviva’s philosophy boils down to “You yearned for babies, but you weren’t interested in forcing the issue…because only an entitled twat thinks life is about getting exactly what you want exactly when you want it.” Questioned by a journalist about her resistance to fertility treatments, Aviva responds, “I’m anti-selling motherhood, I guess. I’m anti-buying motherhood. I’m anti-capitalist motherhood. I’m anti-technocratic motherhood,” to which the journalist observes, “It just seems you’re pretty hostile to procreation.” Aviva can’t deny it.

Her deep-seated skepticism toward the commercial trappings of medical interventions puts Aviva’s longtime desire for children to the test. Fiercely independent and devoted to her husband—a man game enough to visit an absurd sex therapist-cum-witch with an office “decked out in swaths of cheap black velvet bunting and smelled of mildew”—she pushes onward. Her performances become fraught by desire. The increasingly sexy, powerful shows attract more devoted fans.

The late British singer Amy Winehouse enthralls Aviva, who sings covers at shows and her dirges at karaoke; Aviva’s obsessed. Watching interview clips and concert footage isn’t enough; she even connects with Winehouse’s mum in London. In Amy, Aviva sees a girl whose celebrity runs a distant second to the desire to be seen and nurtured within a family. Winehouse’s spirit and legacy buoys Aviva as she negotiates well-meaning hospital chaplains, chaotic international psychedelic retreats, tony fertility appointments, lonely hotel rooms, and horny fellow musicians at festivals, chasing a dream that may not be hers to achieve. Human Blues is a crackling and bighearted novel that doesn’t shy away from hard conversations. These concerns are not just literary themes for Albert; they’re personal, too.

Albert’s 2015 novel After Birth eviscerated taboos surrounding postpartum care and mental health, centering on a friendship between two lonely new mothers. Yet even prior to its publication, Albert responded to what she saw as an urgent need for direct maternal care. In 2012, she trained to become a doula, work she continues to do. In conversation, she relates, “I had to vote with my feet and get my hands dirty, so to speak. I had to put my rage to work, be of practical use, not just spin my wheels intellectually. I love, love, love doing this work.” As a doula, “There’s no theoretical chit-chat. It’s very hands-on, it’s physical, it’s elemental, and it’s really one of the best ways I know of to spend time and energy.”

Albert’s immediate experience informed the writing of After Birth, but its publication didn’t close Albert’s examination of the swirling cultural mythologies surrounding motherhood. The character of Aviva surfaced from this continued engagement. Around the same time, Albert submitted a proposal to write a 33 ⅓ (the series of short nonfiction books that tackle the cultural history of individual music albums) book on Winehouse’s Back in Black. While the publishers didn’t select her contribution, Albert was already knee-deep into a book-length project on Winehouse.

Here, Albert found herself entwined in two projects driven by strong women: “This character [Human Blues' Aviva] had already arrived in this quandary of infertility, menstrual cycles, and the relationship between an individual body and this industrial medical science around fertility.” It was within that tension that Albert realized, “I could write a twinning book in which Amy Winehouse would play a part.” Instinctively, Albert felt this relationship click, but the question of how to reconcile the two forces within this rich context of authenticity, creativity, and fertility was a challenge. Human Blues took seven years to write.

In some respects, the cultural moment had to catch up with Albert’s interrogation of reproductive freedom, bodily autonomy, and perceptions of family. In 2016, Albert taught a seminar at Bennington College on 200 years of feminist literature related to the reproductive body. Her young students were hungry for alternative narratives to conventional motherhood. “It was awesome. Half the students signed up to be doulas by the end of it.” Beginning with Mary Wollstonecraft, the class culminated with the New Zealand writer Julia Leigh, whose 2016 memoir Avalanche tracks her circuitous quest for motherhood. Albert recalls that “Rachel Cusk wrote a review of Leigh’s memoir and Belle Boggs’ memoir The Art of Waiting in tandem in The New York Times Book Review that was such a lightning rod because [Cusk] dared to question assisted reproductive technology and its role in the emotional cultural landscape.” Simultaneously, Albert wrapped her head around Aviva, “who really wants a child, but keeps bleeding, and that sort of clinched it for me. I thought, There is just nothing out there like this.”

As Albert then dove “headfirst” into the project, she reread one of her favorite Philip Roth novels, Sabbath's Theater. What struck Albert most was its “maximalist anti-hero.” To her, “that was the end.” She wanted to grant Aviva the space and time to be a larger-than-life character, to fully convey the vast complexity of a woman whose gifts reside in work that both isolates and floods her with people.

Above all, Aviva’s searching soul cries out to be heard. Her skepticism and passion propel her to speak out, “‘Because whatever gets normalized for women, whatever gets taken from us and repackaged and sold back to us, up and down and round and round, back and forth, wherever, whenever, it’s all so that we keep having to mess with ourselves, while everything else stays exactly the same. So to whatever’s normative, whatever’s expected, we must say…’ She sung it, deep and slow: ‘No, no no.’” Guided by Aviva’s ecstatic, exuberant voice, Human Blues is a powerhouse. The novel carries a bittersweet awareness that while motherhood may be one path to belonging, it doesn’t absolve you of loneliness. While Aviva’s beloved audiences cry out for encores, Human Blues echoes with the truth that we find harmony when we listen first to ourselves.

Lauren LeBlanc is a writer and editor who has been published in The New York Times Book Review, The Atlantic, and Vanity Fair, among others. A native New Orleanian, she lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

You Might Also Like