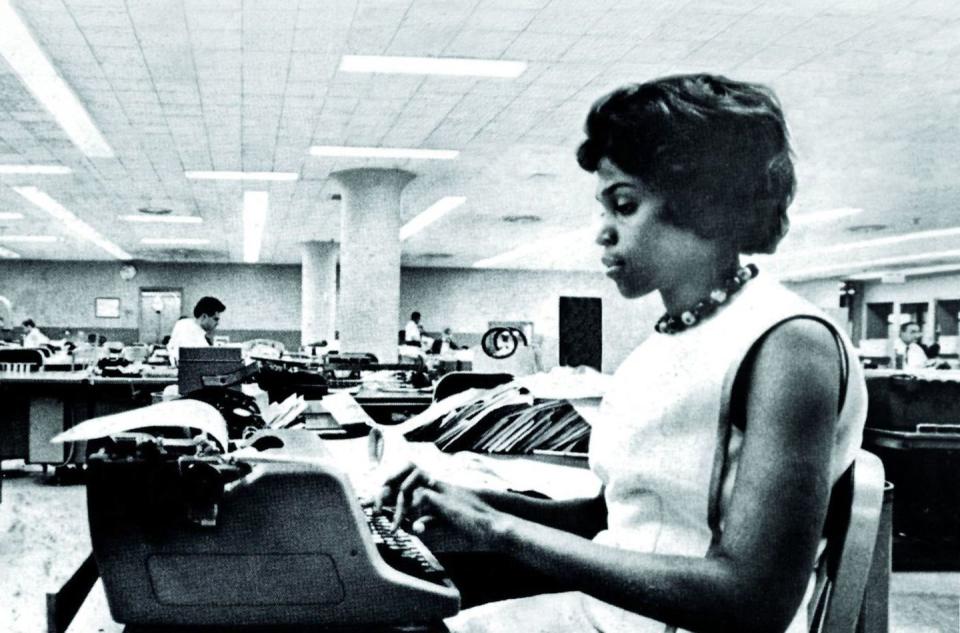

Dorothy Butler Gilliam, Pioneering Black Reporter, on Racism in the Newsroom and the Power of Stories

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

Interview by Kenia Mazariegos/

Photograph by Michael A. McCoy

In 1961, Dorothy Butler Gilliam became the first Black female reporter at The Washington Post, where she went on to become a legendary writer, editor, and columnist.

Kenia Mazariegos: An ice-breaker: What is your biggest pet peeve?

Dorothy Gilliam: One pet peeve would be people who only talk about themselves. Somehow, when people talk about themselves it just feels…small.

KM: You were in your late twenties when Jim Crow ended, so you experienced it firsthand—the depression, the discrimination, the unfairness of treatment. What was it like growing up around that time?

DG: I am who I am because somebody loved me. People in my family, my church, my community. And even though Jim Crow had all hell breaking around us, because of our love and care for each other and the way we conducted our lives—which is very much in the Black tradition—we were able to live a life that gave us strength, that gave us meaning, that gave us a way to be helpful to others. A way to really know that we were not what white people in the Jim Crow South—I guess we’d have to say white supremacist South, even then—we weren’t who they said we were.

KM: Is there a moment in time during your childhood that you realized that you needed to be tough, that this wasn’t going to be easy for you or your family?

DG: As young people, we would be walking to school and white kids would throw rocks at us. Our teachers and our families said, “Don’t fight back, we will not be the kind of people they are.” Not fighting back was tough. But in the end, we feel very much that it was the right way to go because with all that happened, we still just never became haters, even though we knew that our schools were getting the used books and the white kids were getting the new books, and there were just so many obvious discrepancies.

We had a sense of dignity and purpose. My father was a minister. He was a leader in our community. My mother had trained as a teacher but when they moved from the country, where she could teach, to the city, she did not have the credentials that were required. So she worked as a domestic. And as much as I resented that she had to do that, and as much as I’m sure it was difficult for her to be trained as a teacher but to have the only job open to her be a domestic, she was a person who would never let anything destroy her dignity.

I recall where people would call her to come and work for them and they would say, “May I speak to Jesse?” And I would say, “Do you mean Mrs. Butler?” And my mother would say, “Give me the phone Dorothy!” And then, “Hello, this is Jesse.” That always hurt me, but her sense of self and her dignity was much more than what was required.

KM: It must have been easy for some people, during that time, to give up—to not achieve. At what point did you know that you weren’t going to stick to societal norms and that you would pursue journalism?

DG: I was about 17. I was a freshman at Ursuline College, a Catholic women’s college. I got a job at the Black newspaper in Louisville, the Defender, as a secretary. I had been learning to type, and take shorthand, and all those things. And one day the editor came in and he said, “I’m going to send you out to cover a society story because the society editor is sick.”

I was surprised and, certainly, I had never been introduced or exposed to Louisville Black society, but when I began doing that I was able to see that there were so many different worlds. This was a different world—the Black middle class, who had Waterford china, and beautiful dishes, and things that my family didn’t have. It was my ability to see that journalism could open and expose me to new and different worlds that really pushed me into the profession.

I decided I really wanted to train to be a journalist, and I was able, after the first two years, to go to Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri—but at each step, the white supremacy was just always pushing hard against us and all of us. For example, the school I wanted to go to at first was the University of Missouri at Columbia, Missouri, and it turned out that every time a Black woman tried to get into that school, they would find a way to push and not let her enter the school. I ended up saying, I will go where I know I’m wanted! And that was Lincoln University.

I wanted to be able to write stories for the mainstream press that would really show the diversity among the Black community and to show who we were. I mean, when I first arrived at The Washington Post, I overheard one of the old-time editors say, “We don’t even cover Black deaths because they’re just cheap deaths.” To hear that kind of horrible statement coming from a newspaper editor is a good example of how deep this whole system was in American society.

KM: What was happening at the moment you first stepped into The Washington Post as the first Black reporter?

DG: I felt fear and apprehension. When I first walked in that newsroom, I recalled one of my professors at Columbia, where I had finished graduate school, saying, “You have a double whammy. You are going to have a tougher time both for your race and for your gender.” So, that’s saying that my personhood—you know, separate from what I could do, just my very personhood—was going to be challenging in this industry. Yeah, emotions were—as I said in my book, Trailblazer, I felt like I was jumping into a rapidly moving ocean, and I had to jump in with a lot of white men who were seriously anxious to hold on to their power.

KM: You covered the racial integration at the University of Mississippi, where James Meredith was denied admission for being Black. What was that like?

DG: It was frightening. Mississippi’s segregation was so deep. It was a lynching state. I mean, it was a state where Blacks were routinely strung up in trees, and wherein they’d have a lynching and people would come from all over to see it. They’d show the hanging Black body to children. So Mississippi was very angry that James Meredith had the great will to integrate the University of Mississippi because it was a bastion of white supremacy.

I ended up sleeping in a funeral home because there were no hotels for Black people to sleep in. Sleeping with the dead was not an experience that I remember cheerfully, but I was glad to have a place to sleep—and, certainly, nobody bothered me.

The other thing I remember is just the bravery of the people, the courage of the people. I interviewed so many people in the community, and they were filled with fear, yes, but with hope. “My goodness,” they said. “It actually happened! Somebody actually integrated that University of Mississippi.” But then when I went to interview Medgar Evers, it was just startling, his courage, because he said—despite all that was going on, when I left Oxford with the troops, with the Ku Klux Klan walking around with guns being displayed, with all these fanatics from all over the country who came to protest that, you know, the federals were taking over. It happened. Medgar Evers at that point was the NAACP field secretary and when I interviewed him, he said, “Oh, we’re not finished.” He said, “This is just a first step. We’re going to be integrating, you know, all the state colleges.” Blacks were paying taxes that helped to support these institutions, they just were unable to enter them. So, he said, “Our goal is to integrate all of these schools,” and when I heard him say that I thought, What courage!

Seven or eight months after I interviewed Medgar Evers, he was assassinated outside of his house, and what they would say is that this is the price our people had to pay for freedom. And part of it comes from, in the case of Medgar Evers, his love for Black people, his knowledge that things had to change, and his willingness to do what had to be done. He was not naïve thinking that perhaps nothing might happen to him. He knew that, you know, he was being constantly hunted down.

KM: Did his death contribute to your work in activism?

DG: I don’t think it directly did, but I do know that part of my deep desire was to try to make journalism a profession—and I’m talking about daily newspapers then, of course, you know, things have changed tremendously now—but to try to make journalism a place where we could talk about the reality of America. Where there’d be enough people of color to share honestly and to write the stories that displayed the reality of what was going on. One of the things that kept me at the Post for so long was that I was able to begin writing a column in which I could really share my opinion of what was going on, and then I worked as an editor where I could hire reporters who could come in and could write articles about what was happening in the communities from a deep and informed perspective.

KM: Are you happy with what’s going on in the newsroom now, that there’s more diversity, that Black women are able to wear their natural hair on camera?

DG: Yes, even the changes that have happened in the last year, especially after the death of George Floyd and the pandemic, Black Lives Matter—those changes have been very positive. I also want to acknowledge the changes that have been made. I’m happy, for example, that The Washington Post has hired an African American woman as the managing editor for diversity. But I still feel that there’s so much work to be done.

KM: What would you tell a new journalist who’s trying to break into the journalism field, someone who just graduated from school?

DG: Well, I do still mentor people, and there’s a young man I mentor who is not just breaking in, he’s been in a while, but it’s still important to bring all of the necessary skills, and it’s important to bring a level of courage, in terms of writing about subjects that may not feel so comfortable in the newsroom. You’ve got to really understand how to do your work, to do it well, to do it quickly, but you also have to be willing to take some chances and push to do some articles that may not be popular.

I remember when I was writing columns, it got very uncomfortable because I was saying things that they didn’t want to hear, or they didn’t want to print, but they did print them. As a matter of fact, I’m currently compiling a book of columns that I wrote in the '80s and '90s, and part of my wish is to show their relevance to today.

One of the things I did when I was president of the National Association of Black Journalists, I interviewed a lot of the journalists to see how they were feeling, and they were stating that the white editors were very resistant to a lot of their story ideas. I’ve seen the same thing on college campuses. When I was working at George Washington University—I started a program for young people called Prime Movers’ Media—the GW students would come to me and they’d say, “I don’t want to work on the college newspaper because these white editors continue to say ‘That’s not a good story, nobody cares about that." So, it’s really important for editors to have a more open mind, and to understand the importance of diversity, and to write stories about what’s really happening.

I think the media failed terribly during the Trump-era when they gave so much attention to Trump when there were so many other stories that needed to be written, and I hope that there will continue to be a more open-minded attitude on the part of media. People are going to have to change their way of thinking.

About the Journalist and Photographer

Turn Inspiration to Action

Consider donating to the National Association of Black Journalists (https://nabjonline.org). You can direct your dollars to scholarships and fellowships that support the educational and professional development of aspiring young journalists.

Support The National Caucus & Center on Black Aging (https://ncba-aging.org/). Dedicated to improving the quality of life of older African Americans, NCCBA's educational programs arm them with the tools they need to advocate for themselves.

This story was created as part of Lift Every Voice, in partnership with Lexus. Lift Every Voice records the wisdom and life experiences of the oldest generation of Black Americans by connecting them with a new generation of Black journalists. The oral history series is running across Hearst magazine, newspaper, and television websites around Juneteenth 2021. Go to oprahdaily.com/lifteveryvoice for the complete portfolio.

You Might Also Like