What Donald Trump Can Learn From History’s Biggest Losers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“I concede nothing.”

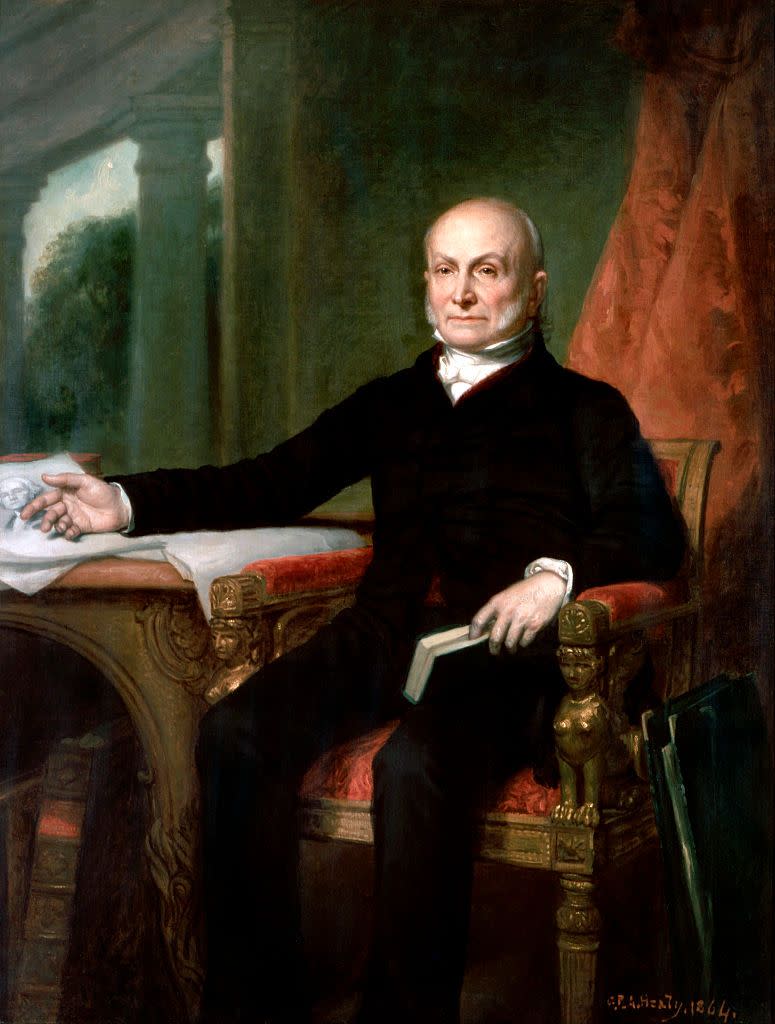

With those three words, tweeted out nearly two weeks after the 2020 U.S. presidential election, which handed him a decisive electoral and popular defeat, Donald Trump took his place in one of the longest and most distinguished traditions that history offers: the sore loser. Nobody, of course, likes to lose, and the temptation to cry foul—or, in this case, “rigged”—when we lose can be irresistible. (Or just to cry anything. On losing to his friend Thomas Jefferson in the election of 1800, John Adams yelled, “You have put me out!”) Just as irresistible is the impulse to dismiss the legitimacy of any competition in which our personal favorites fail to win. How seriously can you take the Oscars, really, when you find out that Hitchcock never won Best Director?

But if history and literature have anything to tell us, it’s that the figures who have earned the greatest admiration are often not the ones who won the battle or the election or the girl/boy, or whatever, but those who knew how to lose gracefully. In our everyday lives, after all, most of us are at least as familiar with defeat as with victory. Virtually every person alive knows what it feels like to miss out on something we yearn for, whether it’s a raise, a promotion, or the cutie at the other end of the bar. For this reason, it’s the stories of perseverance or bravado in adversity or outright defeat that touch us most—that somehow strike us as more movingly human than tales of the greatest triumphs.

This sense that defeat is somehow more revealing of our innermost selves—more, as today’s students like to put it, relatable—is a tradition that goes back nearly 3,000 years, to Homer’s Iliad, in which by far the most sympathetic character isn’t the glittering, half-divine Greek warrior Achilles but the noble, doomed, and all-too-human Trojan leader, Hector, prince of a city that is fated from the start for destruction.

The taste on the part of artists and writers for noble losers has made itself felt ever since, from Shakespeare’s Cleopatra, who at the moment of her fatal defeat dons her royal robes to meet death (“Give me my robe. Put on my crown. I have immortal longings in me”) to the Marschallin in Richard Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier, the middle-aged woman who, bowing to the inevitable, freely gives up her boyish lover to a younger woman.

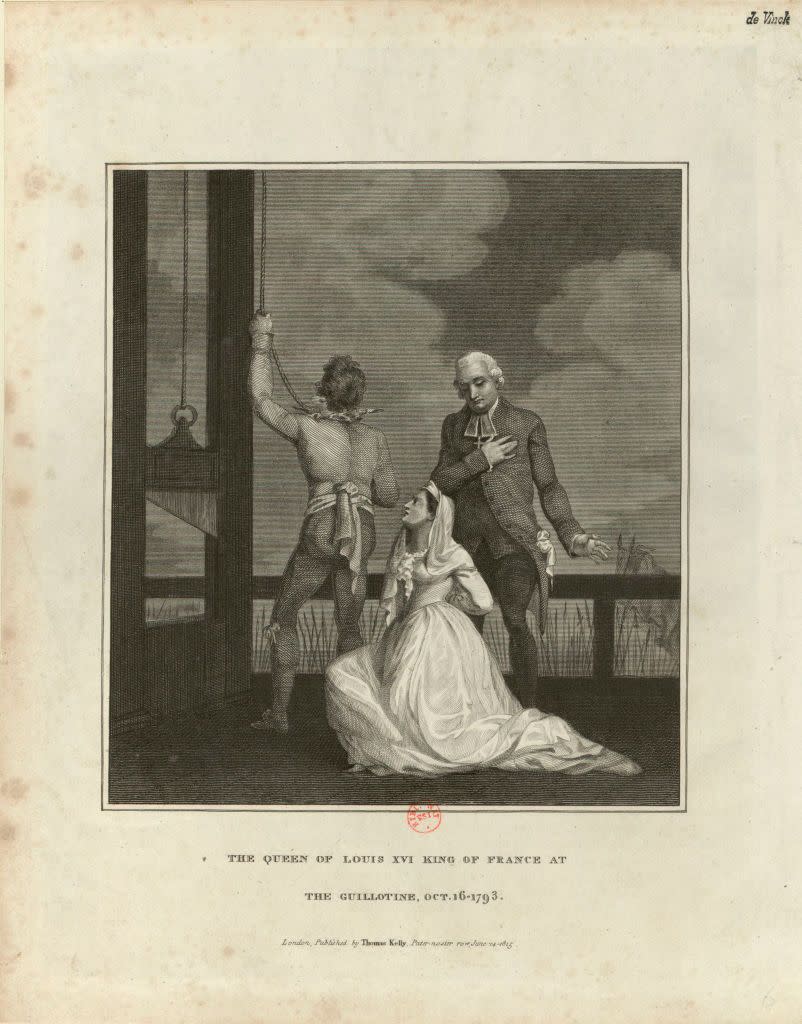

And if the fictional characters we love best are those who yield to life’s harshness while preserving an inner, inviolable aplomb, so too with history’s characters. Even the most ardent revolutionary was likely to be touched by the last moments of Marie Antoinette, who apologized to the executioner who was about to cut her head off after she accidentally stepped on his toe on her way to the guillotine: “Pardon me, sir, I meant not to do it.” (Then again, the French Revolution inspired an unusually high number of classy adieux. “I see you have made three spelling mistakes,” one aristocrat disdainfully noted as he read his death warrant.)

Another way of saying this is that while victory is a showcase for talent, defeat is a showcase for character. As anyone who had to sit through that middle school gym class lecture about ice skaters knows, one way to deal with disaster is to get back on your feet and keep going. In U.S. politics there’s an honorable tradition of electoral losers who have picked themselves up, dusted themselves off, and found ways to make themselves useful. Before the 2000 Bush-Gore contest, perhaps the most hotly contested presidential election in our country’s history was the 1828 race between John Quincy Adams—who, as the son of the second president, was the ultimate political royalty and Washington insider—and Andrew Jackson, who was viewed as an arriviste vulgarian. When the latter prevailed, Adams swallowed his pride and ran again—for Congress: the only ex-president to be elected as a representative, he served for nearly 20 years, until his death in 1848. (Among his other accomplishments, he successfully argued on behalf of enslaved Africans in the Amistad case.) A century and a half later, Al Gore—who owed his defeat to fewer than 1,000 ballots, despite a clear win in the popular vote—did the skater thing too. You could argue that his electoral defeat may have paved the way for other, possibly loftier victories: both an Oscar and a Nobel Prize recognizing his work as a climate activist.

If raw determination is one way to deal with defeat, so is humor. For those of us baby boomers who grew up watching Bob Newhart—the mild-mannered standup comedian and, later, TV genius who alchemized Midwestern affability into comedic gold (his 1960 album The Buttoned-Down Mind of Bob Newhart remains one of the best-selling albums of all time)—it’s shocking to learn that his long-running sitcom failed more than 25 times to win an Emmy: a record. How did he respond? During one Emmy ceremony, Newhart allowed himself to be locked in a box with precisely three hours’ worth of air.

The humorous implication was that the notoriously long-winded affair could be fatal, but the gag also reminded viewers that the Emmys had, indeed, hurt Newhart in the past. Having the last laugh, as we know, is one of the most satisfying kinds of victory. (In politics, too: Adlai Stevenson, who was as famous for his quick wit as for the three times he didn’t make it to the U.S. presidency, once quipped that he would “make a bargain with the Republicans. If they will stop telling lies about the Democrats, I will stop telling the truth about them.”)

Politics and show biz come together in my personal favorite among stories of people who knew how to bow out graciously. In his Lives of the Famous Greeks and Romans, the historian Plutarch tells the story of the Greek conqueror Demetrius “Poliorcetes,” a leader who, during the period of political upheaval and power-grabbing that followed the death of Alexander the Great, distinguished himself for his persistence in bringing down enemy cities (his nickname means “the besieger”) and, even more, for his grandiose ambitions and lavish tastes.

But eventually his pretensions and penchant for luxury exhausted even his own soldiers, who went over to the side of his rival, Pyrrhus. (The latter was the general whose name became synonymous with the worst kind of victory, one in which you win the battle but lose so many of your men that you might as well have lost: a “Pyrrhic victory.”) Acknowledging the inevitable, Demetrius changed out of his royal getup, put on street clothes, and sneaked out of his tent. Describing Demetrius’s greatest moment, Plutarch can’t resist a theatrical metaphor: “Not like a king, but like an actor,” he mused, “he exchanged his showy robe of state for a dark cloak, and in secret stole away.”

Two millennia later, that scene inspired a poem by the Alexandrian Greek poet Constantine Cavafy—a connoisseur, you might say, of history’s greatest losers. Perhaps because he lived in Alexandria, Egypt (a city that itself knew a thing or two about defeat—the greatest cultural center of the Mediterranean world in ancient times, it had become a provincial backwater by the time Cavafy was born there in 1863), Cavafy, a student of both classical and medieval Greek history, based many of his poems on the stories of men and women who made their defeats into vehicles for scoring moral triumphs. One was the Byzantine emperor John Cantacuzene, whose treasury was so depleted by his rapacious predecessor that he had to wear fake jewels to his own coronation—a humiliation that the poet finds impressive rather than “abject.” Another was Marc Antony, the love-besotted Roman general who lost half the Western world when he bet his political and military fortunes on an alliance with the aforementioned Cleopatra; Cavafy urges Marc Antony not to “uselessly mourn” his defeat but to celebrate it with “a final entertainment.” These and so many other great losers in history are reimagined as winners, in the end.

But to be that kind of winner—the winner in the very long run, the kind of person who excites the imaginations of great artists and the admiration of ordinary people, too—you have to be a good loser first. Will some poet be writing admiring verses about the 45th president one day? Something tells me we won’t have to wait for the year 4020 to find out.

You Might Also Like