Decades Later, the World Is Catching Up to Elaine May

Elaine May does not do press.

It’s a quirk for which the elusive writer, director, and actor has become notorious; fans can count the number of interviews she’s given over her six-decade-plus career—including satirical ones she wrote herself—on two hands. She eschews publicists, offering instead the formulaic response to inquiring outlets that she “hasn’t had an interview since 1967!” She also routinely takes her own phone off the line and avoids most public events.

But the spotlight grows ever harder to sidestep. This week L.A. Film Critics announced that May would receive its annual Career Achievement Award. And a few months ago, at 87, she won her first Tony Award for her role as a family matriarch slipping into dementia in The Waverly Gallery (her first Broadway appearance in 50 years). At the ceremony she delivered a characteristically witty speech in which she managed to both spoil the play’s ending and stan Lucas Hedges in one breath. (“My death was described on stage by Lucas Hedges so brilliantly. [...] He described it so heartbreakingly, he was so touching, that watching from the wings, I thought, ‘I’m gonna win this guy’s Tony.’”)

After, she skipped the traditional visit to the press room and returned to her seat to spend the rest of the evening looking…unimpressed. Or was she tired? Or bored? Or just acting for the cameras? With her track record, it’s impossible to tell.

"The Waverly Gallery" Broadway Opening Night

On even the most minor details, May is hard to pin down. Reportedly born to Yiddish vaudeville actors in 1932—she once claimed that reported biographical details about her aren’t 100% true—she spent her childhood touring and performing with her parents. But her father died when she was 12, and life happened fast after that. She quit school at 14, married at 16, and had a daughter at 18—actor Jeannie Berlin. The marriage ended soon after, and May headed off to hitchhike to the University of Chicago—she had heard they’d accept students even without a high school degree—in 1952 in pursuit of something more. She never officially enrolled but fell in with off-beat theater kids who made up the bubbling improv group the Compass Players. (Their founders went on to create famed improv enterprise Second City, a breeding ground for future Saturday Night Live talent.) It was there that May met Mike Nichols, another Chicago transplant.

The pair teamed up on sketches that satirized modern men and women, emphasizing their neuroses. May, in particular, broke new ground: “Women of the ’50s shied away from the aggressive choices required of improvisation,” Janet Coleman writes in her in-depth history of the Compass Theatre. But May dove in. “She was not an ingenue.… She played challenging, sophisticated, worldly women. She was the doctor, the psychiatrist, the employer, the wicked witch.”

And that worked, for a while. May and Nichols soon outgrew the New York nightclub scene, catapulting into the national consciousness. But after May and Nichols split in 1961, their paths diverged. Both went on to direct films. Nichols became famous for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, The Graduate, Silkwood, and Working Girl, helming 21 films in his career. May directed just five, to decidedly lukewarm critical reception.

Elaine May;Mike Nichols

Nightclub comedians Mike Nichols and Elaine May do

Alfred Eisenstaedt/Getty ImagesSince then it has been “close to impossible to see her movies,” as the critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, who coedited the recent ReFocus: The Films of Elaine May, puts it. But even so, May has not faded.

Quite the opposite; she’s resurgent.

In 2013, President Barack Obama awarded May a National Medal of Arts. In 2016 the Writers Guild of America honored her with a lifetime achievement award. A few months later she returned to acting for the first time in 16 years in the Amazon series Crisis in Six Scenes. She has no social media presence, but on Twitter, fandom for May is a constant, whether it’s writer Rachel Syme proposing an “anthology series, but every season is Elaine May” or viral appreciations of her Playbill headshot—a grainy, low-res iPhone selfie. The actor and author Marlo Thomas, who’s known May for decades, notes, “It’s no accident that Elaine was name-checked several times on the first season of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. That’s the kind of historical and cultural impact she’s had.”

If May commented on such matters (and she turned down a request to comment for this article), she might have noted that she achieved all that despite the media, not because of it.

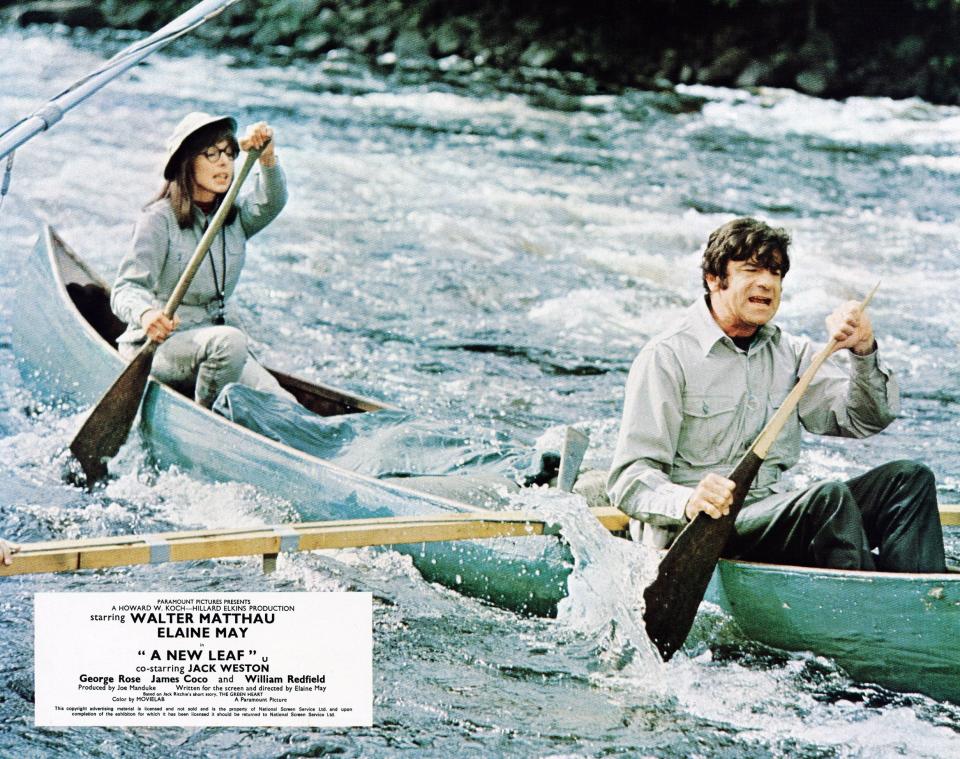

A New Leaf

In 1968, May secured a landmark deal to write, star in, and direct A New Leaf—a film in which Walter Matthau plays a man who plots to marry a bookish, socially awkward heiress, kill her, then inherit her wealth. With that movie, May became only the third woman ever in the Directors Guild of America. But reports piled up about her decision to take Paramount to court over A New Leaf—the studio had wanted something shorter and cheerier than her murder-filled three hour-long cut. She lost.

In 1972 she released her second film, The Heartbreak Kid, to greater acclaim, but critics seemed to attribute its positive reception to the strength of writer Neil Simon’s script. In a review for The New Yorker, film critic Pauline Kael said the film was “in a different league from her first wobbly movie,” suggesting May was better at interpreting others’ work than executing her own.

In 1976 she released Mikey and Nicky, a gritty John Cassavettes–style crime drama that followed two low-ranking mob men double-crossing each other over the course of one long night. But the press had spent the previous months focused on the production’s ballooning budget. (May shot 1.4 million feet of film—more than Gone With the Wind.) The three-year-long editing process became such a battle that May resorted to hiding reels of film in her garage and sued the studio (again) in an attempt to remove herself from the project. Paramount released its own cut, dumping it in theaters over Christmas with next to no promotion aside from an ominous tagline “Don’t expect to like ’em.”

May would not direct another film for 11 years. Her attempted comeback, Ishtar, released in 1987, was an action movie that starred Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman as two bumbling, mediocre middle-age performers who chase dreams of stardom to a gig in Morocco only to inadvertently become entangled in a Middle Eastern political revolution. It was framed from the start as something made solely because its stars owed May favors. (May had made contributions to the scripts for Beatty’s 1981 Reds and Hoffman’s 1982 Tootsie that, though formally uncredited, were so substantial, she was the third person Beatty thanked when he won an Oscar for best director, while Hoffman said that May was “the one who made [Tootsie] work.”) Even the then chairman of Columbia Pictures said he greenlit the film only after receiving assurances from May that she wouldn’t “misbehave” on set. (The same was not asked of Beatty, also a producer on the film and also a notorious perfectionist.) Still, a New York Magazine exposé was riddled with claims about May’s conduct, including rumors that she’d demanded the sand dunes in Morocco be flattened and had trouble directing “boss,” Beatty.

Since then the truth of these stories has been disputed, with some claiming that a studio executive planted them. But at the time, the gossip stuck. Ishtar was dead on arrival. It seemed audacious; a female comic attempting to direct a big budget action movie: “As a writer, May has an extraordinarily weird turn of mind, and on the face of it, she might have been the perfect person to make an updated road picture. But the suggestion that May would be the right director for a picture on this scale has always sounded like a kind of perverse joke,” the Washington Post wrote, with the Daily News simply calling the film “a runaway ego trip.” Costing a reported $40 million—the most expensive comedy to date—and earning only $12.7 million at the box office, Ishtar became synonymous in Hollywood with disaster. It was a career death blow.

It’s been more than 30 years, but her fans are still outraged. Among them is the actor, writer, and director Natasha Lyonne, who became “so obsessed” with May after seeing A New Leaf in the late-’90s. “To look at that body of work and a giant of that magnitude and from there decide that over one movie it should be done? I mean, they certainly let Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman keep making movies,” she says. “I don’t know why [Ishtar] was Elaine May’s problem.”

Her vision of equality wasn’t just getting what the men had; it was being able to act as they did to get it too.

After, May retreated to a life of uncredited script doctoring and playwriting, reappearing briefly in the late 1990s with acclaimed screenplays for The Birdcage and Primary Colors. Though not her final screenplays, they are the last ones that have been made into movies. She never directed a feature film again. “The idea that we, as a society, are robbed of three decades of potentially really beautiful films is the heartbreak,” Lyonne says.

The double standard at work is obvious, though no less infuriating. While such acclaimed male directors as Peter Jackson, Richard Linklater, and the Coen Brothers bounce back over and over from box office failures, women struggle to get a second chance after even the slightest disappointment. And the “artistic genius” that’s tolerated from men—hundreds of takes, abusive behavior, obscene budgets, unfinished films—can cost “difficult” women their careers. Indeed, May might have had more success had she kowtowed to the men in charge. But she didn’t want to be their poster “nice girl.” Her vision of equality wasn’t just getting what the men had; it was being able to act as they did to get it too.

President Obama Awards 2012 National Medal of Arts and National Humanities Medals

In a rare public appearance with Nichols in 2006, May speculated that she encountered obstacles not simply because she was a woman, but because “as a woman, they think I want to show that I’m a nice person. I’m no one to be feared.” At the start of her career, studio heads expected her to bend to their creative wishes behind the scenes while serving as their token woman at the height of second-wave feminism. May wasn’t interested. “When it comes down to it in the end, you’re just as rotten as any guy,” May said. “You’ll fight just as hard to get your way.”

For a new generation of women, it’s precisely that swagger that makes May an example, not a cautionary tale. Lyonne—who regularly retweets anything Mikey and Nicky related—breaks into her signature cackle when citing her respect for May’s “legendary punk move” of holding the film hostage to ensure creative control. And Joan Allen, May’s costar in The Waverly Gallery, insists her commitment to excellence is just as fierce onstage as it is behind the camera. “She’s incredibly detailed and she really, as natural and as off-the-cuff as it seems, she really needs to understand, logically, what is going on in the scene,” she says. “She will not let go until she understands, and she will ask questions and ponder [every detail of a scene] as she’s working on it, and it was very inspiring to me.”

Lyonne takes it one step further: “Genius is a word that’s so deeply overused that it, over time, becomes meaningless, so it becomes a tragedy in the case of Elaine May where you actually want to use it appropriately.”

In an email to Glamour, May’s daughter, actor Jeannie Berlin (who starred in The Heartbreak Kid), echoes Lyonne. “Professionally speaking, I’m one of her biggest fans, and out of all the theatre and movies I’ve done, she is my favorite director,” Berlin writes. “As a mother, she’s totally competent, a good sport, and my big thing is to work up to doing as many chin-ups as she can do.”

“Genius is a word that’s so deeply overused that it, over time, becomes meaningless, so it becomes a tragedy in the case of Elaine May where you actually want to use it appropriately.”

Being a pioneer often requires an eventual sacrifice of oneself for the greater good. Perhaps May knew others would continue on the trail she began to beat down. The world now for female auteurs isn’t a cakewalk, but it has improved some. Look no further than Phoebe Waller-Bridge—who similarly paints unflinchingly truthful portraits of life in Fleabag and Killing Eve—and who has won Emmys for it. “It’s just really wonderful to know…that a dirty, pervy, angry, messed-up woman can make it to the Emmys,” she said as she accepted one.

At her peak, May dealt in similar truths. Her humor isn’t the stuff of feel-good rom-coms; her lightest film is about matricide. Rather, as she herself put it in a rare 1961 New Yorker profile, “[T]he nice thing is to make an audience laugh and laugh and laugh and shudder later.”

Carrie Courogen is a New York–based culture writer whose work has been published by NPR, Pitchfork, Vice, Paper Magazine, and more. Follow her on Twitter @carriecourogen.

Originally Appeared on Glamour