David Bowie Knew I Wasn't Happy. Then He Made Me a Guitar Player Again.

I had just finished touring, opening for Stevie Nicks, when Dave called. It had been a great tour, my first since 1982, and now I was getting songs ready to do When All the Pieces Fit. But I put all that on hold, even though I couldn’t wait to get back to it. Now Dave and I were actually going to play together; we hadn’t done that since the art block stairs in ’62.

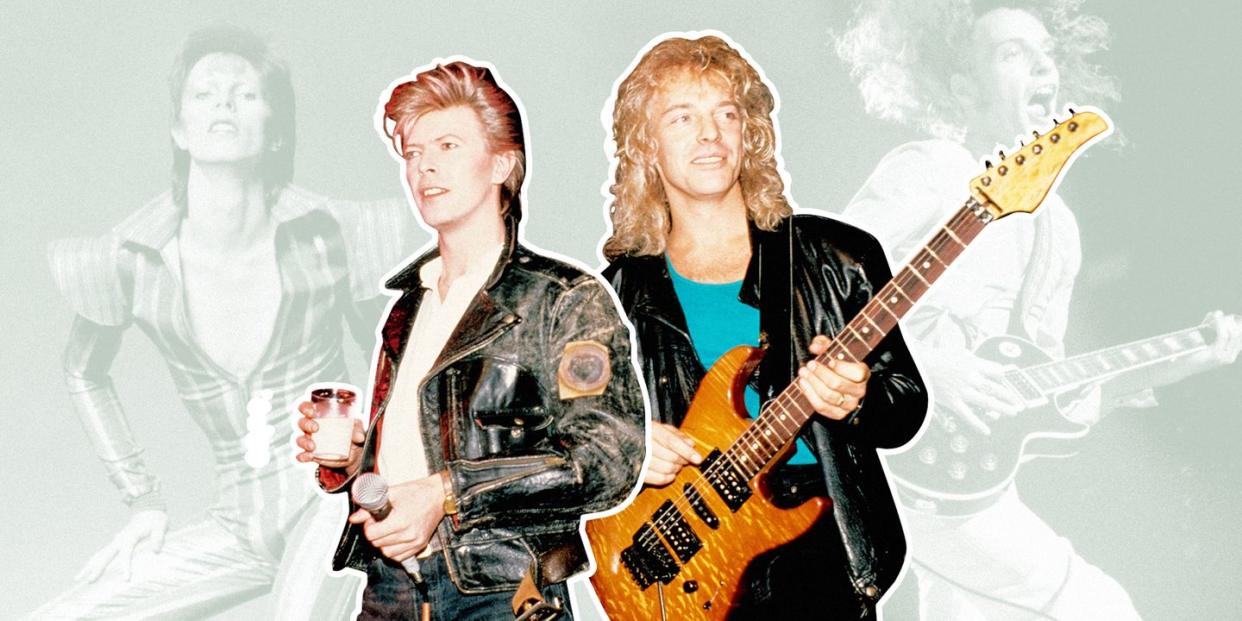

The fact was that he could have any guitar player in the world come out and play with him and he chose me. He knew that the world was confused as to what I was—I’d first arrived in the US as this guitar player with Humble Pie, but then I had this huge record where, yes, there is great guitar playing on it, but there was this perception out there due to my looks and choice of wardrobe that I had slipped back into the teenybopper mode.

Dave saw how the perception of who I really was had changed and knew I wasn’t happy. He gave me a huge gift by taking me around the world, and reintroducing me as the guitar player. I could not and can never thank him enough. That was a huge leg up he gave me, and from that moment on, I started to get my confidence back, and it made a huge difference to me and what was to come.

I went to his house when I arrived in Switzerland and the next day I went to the studio with the engineer. Dave came down and gave me all the lyrics, and we played through the tracks on what would become Never Let Me Down. He said, “See what you can do here and here,” and then he basically left me alone to do whatever I thought would work.

He seemed like he was really into the album. He’d come down to the studio every day after he’d gone to the gym and have a listen, and he was excited. I thought the whole album was great. After Never Let Me Down came out, I now understand, he felt the album should have been different. His next project was Tin Machine, so he certainly did change it up after that—and then many years later, they remixed and redid the whole album!

While we were there, we would go out to dinner and one night Dave said, “I know you’re probably going to go back and do your own album now, but I’m doing this big tour, called the Glass Spider Tour—would you come and play guitar on the tour?” And I said yes in about a nanosecond. I said I would put everything else on hold; this is an opportunity that I can’t miss, it’s wonderful, thank you.

It was the biggest production I’ve ever toured with in my entire life. In Europe, the trucks are a little smaller, but I was told there were forty trucks, 240 people in the crew, and three giant spiders. You had to leapfrog two separate stages, because it took days to put one up. You would perform on one stage and the other would travel, so the next spider would be ready to go. We had yet another one in Australia, which was left there and burned—which is what you do to spiders, don’t you?

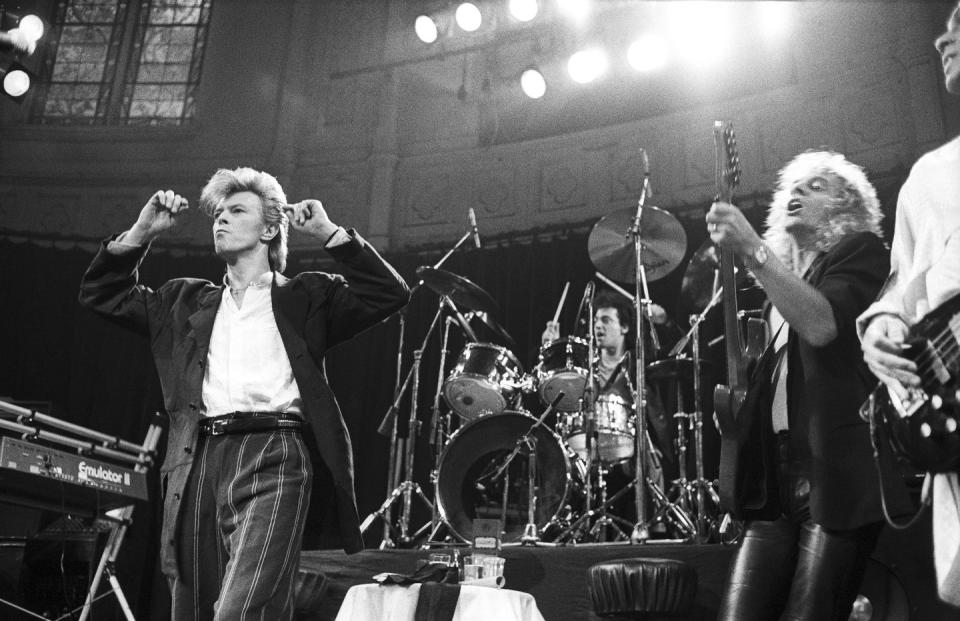

When we were in rehearsals, it was all choreographed and I’m not used to that. There was a stepladder to simulate my entrance at the beginning of the show because they didn’t have “Pete’s Plinth,” as it was called, made at that point. So instead I had to get up on the stepladder. I did it the first time and then said, “I’m not going to do that.” Dave said, “You didn’t get up on the stepladder!” I said, “Well, it’ll be all right on the night—I’ll wait for my plinth.”

Every part of the show had to be staged properly—because there was not only the band and Dave, we also had dancers. It was a great team, great people to work with, except they did sometimes get in the way on stage. At one point in “Let’s Dance,” the dancer, Melissa Hurley, walked backward and stepped on my pedal board and turned me off in the middle of the solo. Another time, during a quiet part my loud button got stepped on.

Dave couldn’t have given me a grander entrance. Carlos Alomar would do this great shredding guitar intro, and then there was all this taped stuff with controlled chaos going on. Then we start the opening song. Just before we got to the guitar solo, I went up these steps up on the back of this gold plinth with room on the top for me to stand. By the end of the number, the light’s off me and I climb back down and come down to the front.

As the tour went on, and people were relaxing a little bit more, they taped a couple of pages out of Playboy on the plinth first, and then it got more and more pornographic each show. Each night the crew were all snickering and pointing at me and I was laughing, too. Every day it’s just getting worse and worse; the last show was over-the-top disgusting, but still funny. When Dave was in The Elephant Man on Broadway, he invited me to see the show and I went backstage after and we were chatting about it. At one point in the show he was in a bath on stage, and he told me, “You wouldn’t believe what the production crew place in that bath some nights—rubber duckies, brushes . . .” Anything really uncomfortable to sit on, I guess.

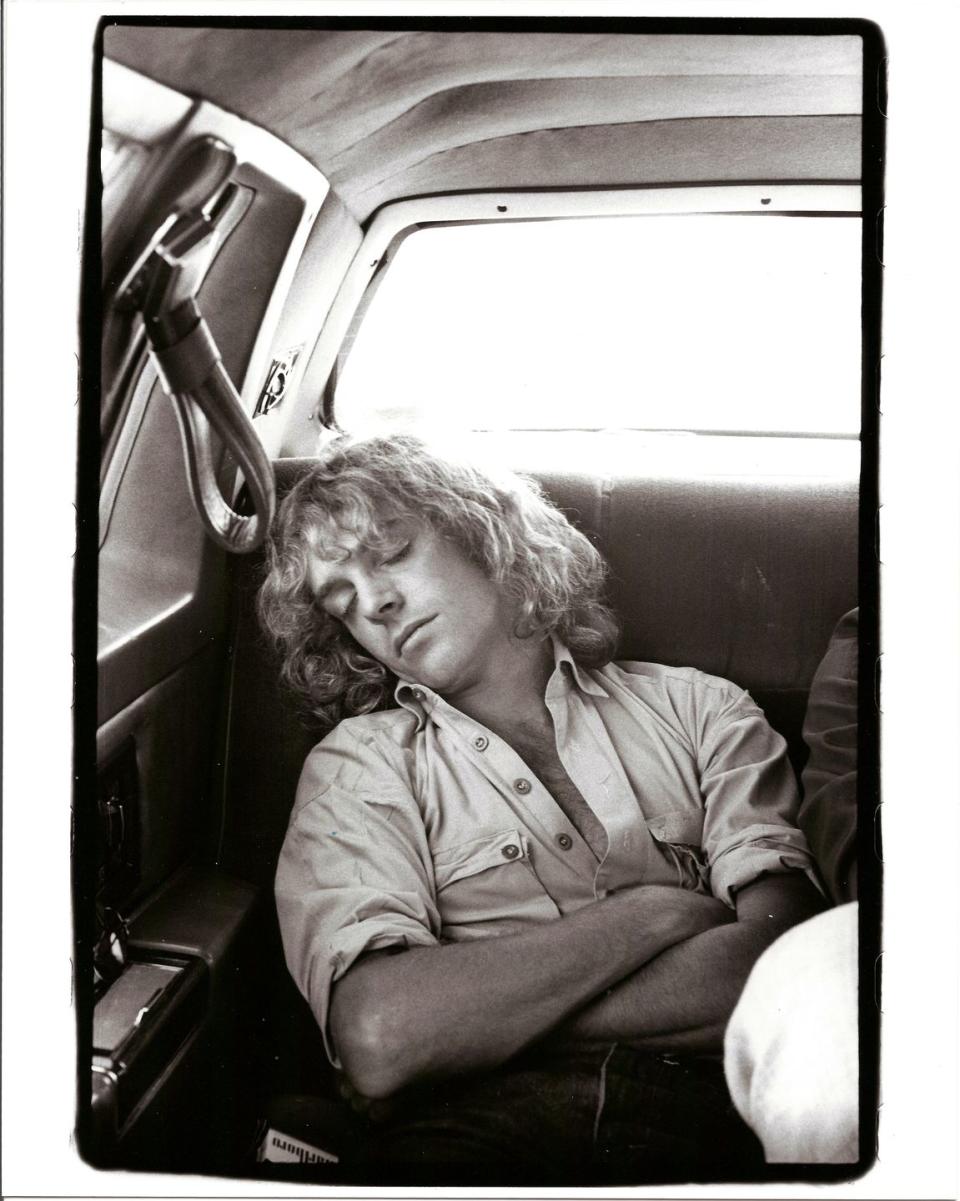

It was a very enjoyable tour; we had a private plane. A bus or large van would pick everyone up, all the dancers and the band, to go to the airport. If we had a bad review, Dave would travel in the car behind, but if we had a good review, he’d travel on the bus. I totally get that! Even for the reviews in a foreign language, we would get a translation from Dave’s publicist.

Playing some of those super iconic guitar parts, like “Heroes”—it was wonderful that I was getting to play these things that all these great guitarists had played. Obviously I’m not Stevie Ray Vaughan or Robert Fripp, so I’m not going to play like either, but I played my version of their parts. It’s pretty much written as to what you play, so it was a challenge; but I love a challenge. I knew that I was going to be compared to a lot of incredible guitar players, and luckily I believe I came out of it pretty well.

I’ve always said, from when I started, that I just want to be the guitar player in a band. Dave wanted me to do more backing vocals, but I said that I just wanted to play guitar. I didn’t really want to sing. But every night was a forum for me to come out there and do my best on these legendary songs. The only time I played any hint of my own music was in “Jean Genie.” In the solo, I slipped in the intro from “Do You Feel” and the crowd went nuts. David smiled; he liked it. It was my way of reaching out and saying, “Hey, it’s me.”

We’d go out to dinner on the tour. One night right before the first date in Europe, he and I got shit-faced together and then they kind of started keeping us apart for a while. He was like me, same thing. There was always the possibility of becoming addicted to anything. I know he became sober in later years, but we definitely tore it up that one night, just the two of us.

People would ask me to talk to Dave about stuff, because they knew he’d listen to me. But we had a personal relationship and a business one; he was the boss and I played guitar for him. When we were together, it was the same as usual. I never called him David; I always called him Dave, because I knew him as Dave from school. He was a very caring person. After he’d passed, I sent Iman an email saying what a great older brother he was to me, always there to help when needed.

Dave was a regular kind of guy. The persona portrayed on different albums and tours was an act. It was all carefully worked out. He’d reinvent himself all the time and he knew what he was going to be—it was a new character each time. He was a great actor. Meanwhile, he still had this amazing ability, lyrically, musically, and vocally, to write all those legendary, thought-provoking songs.

But that tour set me up for what was to come. On my farewell tour, we had a great video opening: all these pictures of me, bands, and people I’ve known start to appear, first slowly then really fast, building up into a crescendo and ending on a video of Dave pointing and saying, “Peter Frampton on guitar”—it’s film from the Glass Spider Tour—and then I walk on stage. He brought me on, which is so cool. I thought because it was the last tour, it would be great to have Dave introduce me. Thank you, Dave.

While we were on the Glass Spider Tour, I found out Dave was really frightened of flying—though I shouldn’t laugh. After about my millionth flight, I’d reached a point where I started getting bad, too, so I decided I would learn to fly. For my tour in ’79 we had our own plane, and both our pilots were also flight instructors. So Rodney Eckerman and I would go back to the airport on days off and take lessons. I ended up with a whopping fifteen hours, but learned that you have to almost force a plane not to fly unless there is a mechanical problem or pilot error. (Oh, and it’s always advisable to make sure you have enough fuel before you take off. You’d be amazed at how many accidents happen by pilots running out of juice.)

So by taking a few lessons, I’d exorcised my fear. I still have my logbook, but I never continued flying after the tour. One day, our pilots hadn’t been available and I had an instructor who really wanted me to do my first solo flight. I already had over ten hours in a Cessna 152 and had been landing and taking off with no help from the pilot sitting next to me. I would have liked to solo, too, but this was a new airport for me. It was a little rural airport with a narrow runway with major power lines crossing the start of the runway. So you couldn’t do a normal approach, but had to stay higher than usual to get over the power lines and then drop down quickly to land. Needless to say, I didn’t think that should be the first and last landing I ever made, especially at this airport.

Anyway, Dave was not a fan of flying at all, but we always had great planes. Once, we had to use a different one ; it was a 727, like our regular one. We’re on the runway and it starts to move, and you know how sometimes when the air conditioners come on, they kind of put out a fog, which is actually condensation? Well, there was an awful lot of condensation this time, and it did look a bit like smoke. So Coco, who was Dave’s right-hand lady, and Dave started yelling “Smoke! Smoke!” Coco starts running to the back—we’re already taxiing to the runway, and she goes to open the back door and the flight attendant runs back shouting, “Stop, stop, don’t do that!” I don’t believe the door would have opened due to the plane already having been pressurized. But if you did open it at altitude, you would be sucked out of the plane.

So the pilot pulls off the runway, and we stop. The flight attendant opened the door at the back and a chute came out, which inflated for everybody to slide down away from the plane. As Dave came down the aisle, he grabbed me, and put me in front of him, and then pushed me down the slide. He made sure he got me off the plane before himself. Another thing I thanked him for. He was always there looking out for me.

There was a bedroom suite on the plane, with gold faucets and the whole thing, but Dave never would go in. He and Coco would take turns sitting on the jump seat right at the back of the plane, as close to the exit as possible, rather than be relaxed and comfortable in his private space.

Barbara and Jade came on the plane a couple of times. Jade would hang out in Dave’s room, watching videos on his TV, and come up to him and—she was three or four—say things like, “You promised me you’d come and play with me.” And he was great with her. She got on his case a couple of times. She called him Davin Bowie—“Davin, you haven’t played with me yet.”

We didn’t spend that much time together over the years, but it was almost a brotherly relationship. He was protective of me, and I think it also had to do with the relationship he had with my dad. He was family.

Excerpted from DO YOU FEEL LIKE I DO? A Memoir by Peter Frampton. Copyright © 2020. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

You Might Also Like