With DACA phasing out, college graduates like Edder Martinez face an uncertain future

Before Edder Martinez was a college graduate, he was an ICE detainee. “I spent my 20th birthday in immigration detention,” says Martinez, a DACA recipient and new alum of Arizona State University’s Class of 2018. “It was easier for you to go to jail than it was for you to go to school — that’s what life without DACA was.”

Mexico-born Martinez, 27, crossed the border with his mother when he was 5 years old. They settled with relatives in Phoenix in 1995, and Martinez’s mom immediately placed him in school. “The reason why she came to this country was for her children,” says Martinez of his undocumented mother. “To give her children a better education and better opportunities.”

More than a decade after graduating from high school, seeing no clear future, Martinez is back in the same uncertain situation — one that previously landed him in immigration detention and on the path to deportation.

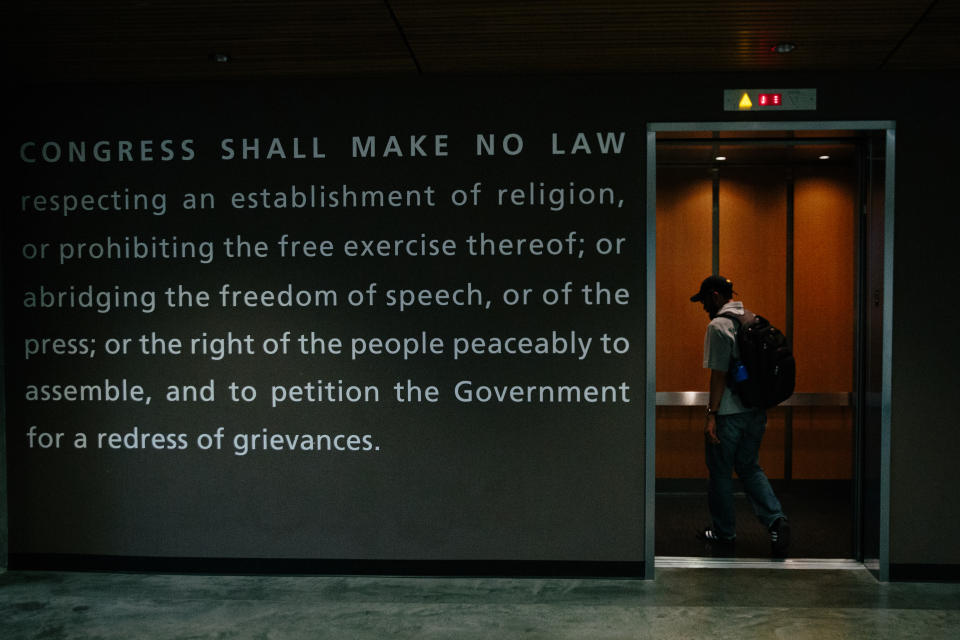

Martinez is considered a “Dreamer” — an undocumented immigrant who was brought to the U. S. as a child. The Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, which was introduced in Congress numerous times but never enacted, would have canceled deportations of undocumented immigrants who entered the U.S. before their 16th birthdays. It also provided for a pathway to citizenship through college, employment, or military service for current, former and future undocumented high-school graduates and GED recipients.

Two years after the DREAM Act finally passed the House in 2010 but failed to get through the Senate, President Barack Obama established the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) initiative by executive action. Immigrants who would have been covered by the DREAM Act became eligible for a work permit, a Social Security card, a driver’s license and deferred deportation. They had a chance to work legally, afford college and travel without fear of being discovered to be undocumented. DACA gave nearly 800,000 Dreamers a degree of certainty.

But that assurance was upended last September when the Trump administration announced an end to DACA. President Trump gave Congress six months — until March — to come up with a permanent replacement for DACA. Two immigration bills are now being negotiated by GOP conservatives and moderates — one a hard-line bill introduced by Rep. Bob Goodlatte, R-Va., and a more moderate “compromise” bill put together by the House leadership. Both bills have tough border security provisions, but only the compromise measure would offer a path to citizenship for the 1.9 million immigrants covered by DACA.

Both bills would satisfy Trump’s four main pillars of immigration reform. They would end the diversity visa lottery program, establish a new merit-based green card program while restricting family-based “chain” migration, end “catch and release,” and provide $25 billion for a border wall — with a provision that if Democrats rescind funding for the wall, new visas for Dreamers would be blocked.

Democrats have said they won’t support either bill. Along with GOP moderates, they have threatened a discharge petition to force a bipartisan vote on DACA. Whichever bill passes the House will need the support of Senate Democrats and President Trump to become law.

Meanwhile, first-time DACA applicants are no longer being accepted. And beginning in March, current DACA permits began expiring on a rolling basis, with about 33,000 individuals losing protection each month, according to the American Council on Education. They will need to start making decisions about their education, jobs, military careers and where they will live if they are forced to leave the only country they’ve known since they were children.

Like many undocumented children and young adults, Martinez admits he did not know he was undocumented until it mattered.

“Everybody kind of knows that they are [undocumented,] but they don’t realize the implications of what that really means,” says Martinez. “You start realizing it when you can’t go and get a driver’s license; you don’t have any health insurance; you have difficulty going to another state, [and] your parents are apprehensive about you leaving on school trips.”

Still, Martinez hoped to live his life “like any other regular American kid” and go to college. After graduating from high school in 2007, he looked forward to studying pre-law at Arizona State University — but his plans fell apart when he received his bill for the first semester.

“That’s when I realized that due to my immigration status, I had to pay three times as much as any other Arizona high school graduate,” says Martinez, who was charged tuition at international student rates. “That made it very difficult to start my college education.”

“DACAmented” students cannot receive federal student aid, work study or — in some states, like South Carolina and Alabama — in-state tuition, even if the DACA student has spent a majority of his or her life living in the state. After DACA, some state laws and policies allowed recipients to qualify for in-state tuition while others required undocumented prospects to apply as international students. Doing so came with higher tuition rates, making college out of reach for many DACA high school graduates.

With no way to afford college, Martinez dropped out and faced limited options. “There was no DACA; there was nothing,” says Martinez. “You didn’t have the opportunity to go to school; you didn’t have the opportunity to work legally, so you had to find odd jobs — low-paying jobs that would take you.”

Martinez found jobs that paid him under the table — one at a scrap yard and another at a pizzeria he says was in the “nicer part of town.” At the pizza shop, he worked alongside other undocumented employees, one of whom sold Martinez his first car.

“Having a car was a necessity,” says Martinez. “It was liberating. It gave me independence.” But while Martinez no longer had to depend on limited public transportation, he had to worry about getting pulled over by police.

Martinez recalls being pulled over at least three times. Local police gave him tickets for traffic violations, such as driving without a license or not having a license plate light. Martinez says he fell behind in paying the tickets because didn’t have a constant source of income or a steady job.

He stopped driving. “I knew it was safer for me not to drive,” says Martinez, who then began using public transportation.

One night in 2010, Martinez made a small mistake that would land him in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody. “I crossed the light-rail tracks at the wrong end,” says Martinez, who was heading home from a concert. “Light-rail security stopped me, asked for my ID.”

Martinez could not provide any. “They took me to Sheriff Joe’s jail,” says Martinez, referring to sheriff of Maricopa County, Joe Arpaio. Arpaio was known for his “crime suppression” sweeps, instructing police and volunteers to ask detainees they profiled as “illegal aliens” for proof of citizenship. The sweeps started in 2008, a year after Martinez graduated from high school. In 2010, they were followed by “The Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act,” or Arizona SB 1070, a controversial state law requiring law enforcement to question anyone they stopped and had “reasonable suspicion” of being in the country illegally. SB 1070, the country’s toughest law on immigration enforcement, criminalized undocumented immigrants and sparked protests and legal challenges from the ACLU, civil rights groups and the U.S. Department of Justice.

At the 4th Avenue jail in downtown Phoenix, Martinez was told he had a warrant for his arrest for contempt of court. He’d been taking care of Phoenix traffic tickets, but had not shown up to court for outstanding tickets given to him in other municipalities where he’d been stopped by police. He was handed over to ICE when it became clear he was undocumented.

In 2010, days before his birthday, a 19-year old Martinez entered Eloy Detention Center, located southeast of Phoenix in the desert. Had his situation been different, Martinez would have been a junior in college, living in the campus dorms with roommates, joining school clubs and buying books for his classes.

Instead, he slept on bunk beds in two-person cells, took “free time” in the evenings to socialize and learn to play chess, and read books he found. Said Martinez, “I tried to be productive” while awaiting deportation proceedings.

He spent two months in detention. His mother couldn’t visit because she was undocumented and the facility was two hours from their home. Martinez paid for phone calls, where he listened the cries of his mother, who feared he would be deported before she got a chance to see him again.

“Why I wasn’t deported was because of the ‘Morton Memo,’” says Martinez. John Morton, then the Deputy Assistant Secretary for ICE, had issued a memo two months before Martinez’s detainment, focusing on removal of serious offenders. This restructuring priority fell in line with the Obama administration’s approach to immigration enforcement. While other detainees with serious criminal convictions were deported, Martinez was treated with more prosecutorial discretion.

An immigration judge set Martinez’s bond at $15,000. “They considered me a flight risk,” says Martinez. “They thought that because I was already irresponsible enough — not paying my traffic tickets — I wasn’t going to show up to immigration check-ins.”

Martinez’s mother raised the money to get her son home, but Martinez still had to check in with an immigration judge periodically as his deportation proceedings went forward.

Home in Phoenix, Martinez joined community organizers in advocating for the DREAM Act and helped Latinos in his county with voter registration. He was motivated to get involved with social justice issues, but above all else, Martinez wanted to make his mother proud. “I tried to make up for the terrible times I made her go through,” he says.

True freedom for Martinez came in 2012 when, following the implementation of DACA by the Department of Homeland Security, an immigration judge ordered an administrative closure for his case, suspending Martinez’s deportation proceedings altogether. The deferred action allowed children brought to the U.S. illegally to apply for a renewable, two-year protection from detention or deportation. Martinez and 800,000 children of undocumented immigrants now could apply for temporary permission to stay in the U.S.

“DACA gives you peace of mind,” says Martinez. “Without DACA, you don’t have a way of identifying yourself. You’re back in the shadows.”

Martinez sought an attorney to help him apply for DACA.

To qualify for DACA, you had to be under the age of 31 as of June 2012 and have entered the U.S. before your 16th birthday. You had to prove that you had lived in the U.S. for at least five years before DACA was enacted. You had to be enrolled in school or pursuing an education. And you must not have committed a felony or significant misdemeanor. Those who met the criteria received DACA status and could get a work permit, a Social Security card, driver’s license and permission to stay in the U.S. without fear of deportation.

When Martinez received DACA status, he also got a chance to return to Arizona State University. In 2013, Martinez returned to the classroom, enrolling first in a community college then transferring to ASU. He worked, this time legally, and tried to make ends meet to pay for the first couple of semesters of school until he earned scholarships.

“DACA has always been about young people of a certain age who came to this country and who have gone to school and are trying to make a path for themselves in American society,” says Terry Hartle, senior vice president of the American Council on Education, which represents nearly 1,800 U.S. college and university presidents and executives. “And obviously, education is an important part of that.”

Nationally, about a fifth of DACA recipients — whose average age is 25 — are enrolled in college, and about four percent have already earned bachelor’s degrees, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Over 90 percent of DACA beneficiaries are employed.

Hartle says the end of DACA would “replace modest certainty with total and complete uncertainty” for many of these young people. “If the DACA registry disappears,” says Hartle, “the future of those individuals in educational institutions, as employees, as residents of the United States is very much uncertain.”

Opposition to DACA amnesty is based on concerns about vulnerabilities in the vetting process. “We know so little about the DACA population,” says Jessica Vaughan, director of Policy Studies for the Center for Immigration Studies, a research institute that examines the impact of immigration on American society. “We know that some people with criminal convictions were allowed to get DACA. It would be good to know did those turn into bigger criminal convictions later and do we need to set the bar higher.”

Vaughan said she wants to see complete data for DACA recipients and “make sure the program doesn’t become a problem, rather than just assuming that these are all high-achieving graduate students who are curing cancer — the stereotypical portrait that’s given of someone with DACA.”

While she acknowledged the achievements of DACA recipients, Vaughan advises against generalizations about the entire population. “Yes, there are some very accomplished, high-achieving people who have DACA. In part that could be because they got DACA and were able to go to school and pay in-state tuition,” says Vaughan. “But there is a significant share that never finished high school.”

Martinez is a new member of the small group who have finished college; many are the first in their families to do so. He graduated in May with his bachelor’s degree, which today hangs on a wall in his living room.

Martinez is constantly reminded of what he survived to get where he is today. A block from ProgressNow Arizona, a public policy advocacy group where Martinez works as the communications coordinator, is an ICE field office. It is the same Enforcement Removal Operations office where Martinez says he had been processed before being sent to Eloy Detention Center.

On his way to work, on lunch breaks or on his drive home, Martinez says, he sees buses pass by filled with people. “I’m constantly reminded that I’m just one of many, and I was able to make it out and not get deported,” says Martinez. “I think about the people who didn’t make it out and did get deported. They were behind bars for trying to seek a better life.”

Martinez dreams of attending law school, but his future — like that of all DACA recipients — is in limbo.

Since the announcement of the DACA phase-out, anti-immigration decisions have been rolling in. In April, Arizona Supreme Court struck down in-state tuition for DACA students, which could force some to drop out of school. In May, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a decision declaring immigration judges can no longer administratively close deportation cases, as was done for Martinez. The directive could put thousands of closed deportation cases back on federal court dockets.

This week, Trump meets with House Republicans to discuss immigration legislation and border security.

Martinez is paying close attention to the news, remaining informed and civically engaged. “I don’t have influence when it comes to administration officials like Jeff Sessions or Donald Trump,” says Martinez. “But I can ensure that folks get engaged, get involved and they vote. The elections are too important this year; too much is at stake right now.”

DACA is one of the issues at stake. Martinez holds no grudges about his tortuous path to his college degree. Instead, he says the experience taught him not to take things for granted, “to stay rooted and keep my feet on the ground.”

“DACA changed my life,” says Martinez, who has renewed his status twice. “DACA allowed me to pay in-state tuition. I was able to work legally, get a Social Security number. I have a work permit. I was able to get a new job and pay taxes. Hopefully, we get something permanent, but if nothing permanent happens, then hopefully DACA is still there.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Key Democrat: Trump advisers were ‘lying through their teeth’ when testifying about Russia contacts

Stephen Miller, meet your great-grandfather, who flunked his naturalization test

Businesses have made millions off Trump’s child separation policy

The dominance game, as played by dictators and other animals

Democrats look to gain in Southern California as outrage mounts over family separations

Photos: Melania Trump makes surprise visit to migrant child facility in Texas