This Cyclist Now Rides for the Pure Joy of It—Not to Escape Her Past

This past July, Alex Showerman went on a mountain bike trip to North Conway, New Hampshire, with two of her closest friends. The three women ripped around the trails of North Conway, hike-a-biked, jumped into swimming holes, and camped. Although the trails were full of challenging features—sharp and chunky rocks, roots, and steep, technical singletrack—Showerman had never felt so free and at peace on the bike. She was riding for the pure joy of the sport, rather than to outrun the shadows of her past.

Originally from Thetford Center, Vermont, Showerman, 32, can often be found catching big air off of jumps on dirt trails or snowy slopes, with her regal German shepherd, Gus, bounding by her side. She resides in a house with three other women in Golden, Colorado, and in their garage are seven bikes, one snowmobile, a heap of climbing gear, three snowboards, and five pairs of skis. Committed to building brands that “disrupt the status quo,” Showerman started her own values-driven marketing agency this past summer, and she’s also an ambassador for Wild Rye, Weston Backcountry, and Picture Organic Clothing.

Want to become a stronger, healthier rider? Sign up for Bicycling All Access

But for the last three decades, life was radically different. At birth, Showerman was assigned the male gender. Society told her she was a boy, but Showerman always knew otherwise—from her earliest memory, she went to sleep wishing she would wake up a girl. She didn’t have a single “a-ha moment,” but rather there was a gradual unfolding of realization, understanding, and acceptance.

“As far back as I can remember, I knew this was something I had to hide and feel ashamed of,” Showerman told Bicycling.

Growing up in the 1990s, in a predominantly straight, white, rural Vermont community, Showerman suppressed her identity in order to be accepted. She was guarded in her relationships, and even her brother remembers her being “kind but aloof.” She put on armor to live life as a boy every time she stepped outside her bedroom.

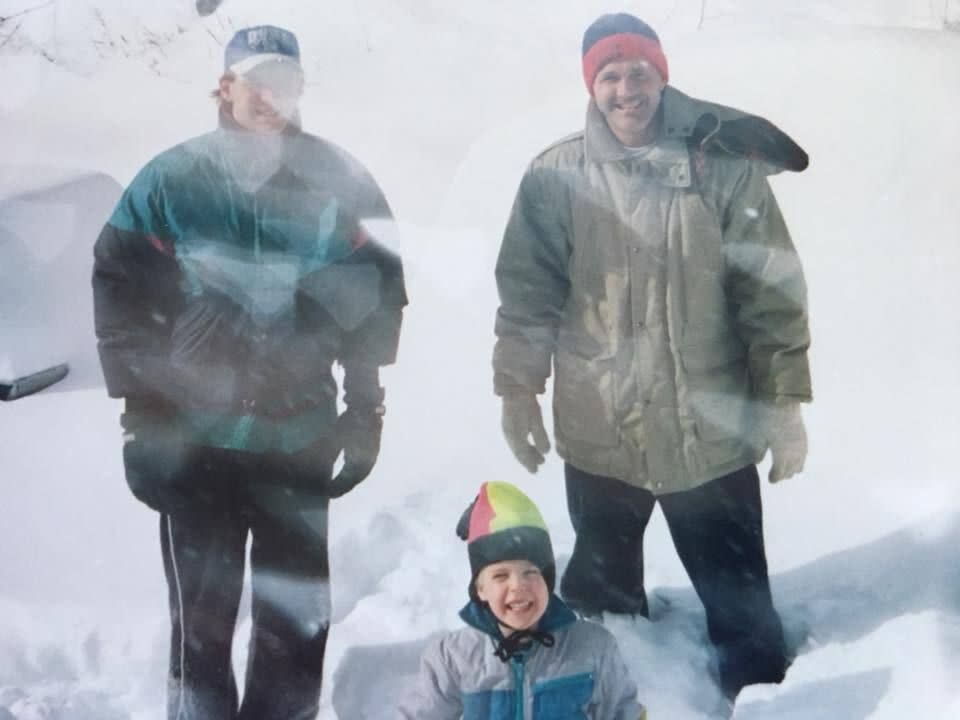

As a child, Showerman preferred being outside all day with her neighbor and best friend, Ema. They were always off on adventures in their small town, exploring forests, climbing trees, and building forts. In middle school, Alex rode BMX bikes and skied, and excelled at ice hockey.

Rather than risk being ridiculed, ostracized, or assaulted, Showerman presented as male and taught herself to create a socially acceptable persona: a stellar student-athlete who shined in school, at cross-country running, at snowboarding, and in the chorus. No one would have seen her misery, emotional pain, fear, and isolation.

As much as Showerman blended in among her friends and fellow runners, she was still teased and taunted in the locker room for not objectifying women or bragging about sexual conquests. Because Showerman showed respect for girls at school, guys called her “gay” or other homophobic slurs.

“Those insults cut deep,” she said. “I knew I wasn’t a male who liked males. They were wrong about me.” But wanting to fit in, she stayed silent. And because she appeared male, she wasn’t accepted as one of the girls either.

The solace that Showerman had once found in outdoor sports as a kid now became another source of pain, as she encountered misogynistic “bro” culture in snowboarding and mountain biking.

“I was not experiencing the world as I wanted to, and the world didn’t see me as I wanted to be seen,” she said.

Twenty years before breakout transgender roles and characters were featured on critically acclaimed shows like Orange Is the New Black and Sense 8, Showerman didn’t see herself represented anywhere. She had no role models or mentors. And even if she did, she still felt she lacked the courage to describe the dichotomy she was living. Showerman worried that if she confided in anyone, she risked becoming even more of an outcast than she already felt.

Ultimately, she faced a question: If you don’t see yourself represented anywhere, how do you orient yourself and become who you want to be? How do you know it’s okay to even be yourself?

Without anyone to identify or connect with, depression took hold. To numb the pain, she turned to alcohol—better to feel nothing than face the daily discomfort of feeling incomplete.

“Generally, when you don’t understand something you are afraid of it, so I had a lot of fear around my feeling of not being normal because I couldn’t understand what it was. The internalized fear, combined with the external shame, was a potent cocktail of negative emotions,” Showerman said.

In 2015, Showerman started seeing a gender therapist to help her identify and understand what transgender was. She lived presenting as a male for 31 years of her life, up until recently.

This past July, Showerman came out to two trusted friends whom she had met five years ago through her trail advocacy work at Perry Hill, one of Vermont’s premier trail networks: Rosy Metcalfe, who works in public health, and Louise “Weezie” Lintilhac, former managing editor at Backcountry magazine. They originally bonded through the local mountain bike community’s “Waffle Wednesdays” in Waterbury, Vermont, a weekly gathering where they made different kinds of waffles depending on the theme.

Metcalfe and Lintilhac took Showerman on that life-changing mountain bike trip in New Hampshire. Still in the closet to everyone else in her life, this was the first time Showerman rode as her true self: a woman.

“Once I accepted myself as transgender, so much of my life made sense,” she said. “There is power in being able to name what you’re feeling. When you can name it, you can own it.”

The difference between riding with women versus men was eye-opening for Showerman, as well. On rides with men, when she still presented as male, she described, “When you got to something challenging, you either rode it or you didn't. There was an unspoken competition.”

During those rides, Showerman would also avoid having to do any bike repairs. She would ride “dirty,” without tools, plugs, or tubes to fix a flat tire. On one ride where Showerman had a flat, a male friend dropped his tools and a spare tube with her and continued riding, leaving her solo and stranded.

“I always felt so self-conscious because I wasn’t great with mechanical things, and there was an expectation that [because you were a guy] you just knew how to [fix] it. I would rather walk out than look like I didn’t know,” she said.

By contrast, when riding Mount Kearsarge during their trip, Showerman had not one but two flats. Metcalfe and Lintilhac stopped immediately, and, like a well-oiled pit crew, promptly opened up their packs for tools and worked together to fix Showerman’s tire and get her bike rolling again.

“Who knew having a flat could be fun?!” she said.

When any section felt too advanced and problematic, they all stopped and collaborated to figure out the best lines and ways to ride it out. With women, her rides turn into workshops. There’s a sense of “let’s all figure out this section together,” Showerman said. “The more I ride with women, the stronger of a rider I’ve become.”

Although they’d been friends for years, she bonded with Metcalfe and Lintilhac in a new, deeper, woman-to-woman way when Showerman came out. In Metcalfe and Lintilhac, Showerman sees not just the kind of rider she wants to be, but also the type of person she wants to be: inclusive, helpful, warm, welcoming, and encouraging. And of course, a badass athlete.

As the outdoor industry—bike and snow alike—is slowly shifting to greater parity in sports and beginning to celebrate women athletes not simply for their looks but for their abilities, so too is Showerman beginning to find people with whom she can identify.

The more Showerman rides with women, the more confident, supported, and skilled she has become at mountain biking. She’s less afraid to fail and make mistakes on the trail, and she’s less afraid to be her true self.

“I now feel so much happier. I feel like I found my place, my voice and my purpose. [Coming out has] been the best thing I have ever done,” Showerman said. “This is me. It might not be who you want me to be, who you expect me to be, but I’m a woman.”

You Might Also Like