Crisis, what crisis? How the classical music industry is defying Covid

In the world of classical music performance, it’s been a tale of unmitigated gloom since lockdown began in mid-March. All concerts were cancelled, and are only now restarting. Stuck indoors, deprived of live performance, the classical music and opera lover has had to get by on streamed events, played in empty venues.

But, while the pandemic has been a disaster for live concerts it’s been a boon for the recording business. “We saw a surge in sales from day one of the lockdown, up more than 60 per cent on the same period last year,” says Chris O’Reilly, CEO of the UK’s biggest specialist classical retailer Presto Classical. “The bulk of that was from downloads, which saw a rise of 63 per cent, but CDs were also up by 23 per cent.

“We thought there might be a problem of supply, but apart from Warner Classics closing its warehouse for two weeks there have been no problems.”

Record companies themselves also report steady figures.

“People had no time for listening in those first two weeks, they were too busy getting their lives together,” says Per Hauber, head of Sony Classical International. “That’s why the market for film streaming, children’s games, audio books, and keep-fit videos all went through the roof. But then, when life found a new normal, people went back to streaming and buying CDs, and our sales recovered.”

Other companies report the same: a dip followed by a strong recovery. But sales is only one half of the business. The other is the schedule of recording sessions and post-production and marketing which ensures that every month there’s a shoal of new releases to offer the public. Here things have been much more challenging.

Simon Perry, the CEO of one of the world’s great small independent labels, Hyperion, says he cancelled all recordings up to July. “That really hurt, as we had some wonderful things lined up, but our customers so far haven’t noticed any difference, because we always work a year ahead and have plenty of releases in our stockpile,” he says.

Since July, though, recordings have gradually recommenced. “You have to observe social distancing, which is really difficult,” says Perry. “But we’ve been able to make recordings with the Nash Ensemble with just a handful of players, and with the Gesualdo Six, a small choir, and also the pianist Stephen Hough, who has made several new recordings for us.”

Hough has become one of Britain’s best-known classical musicians partly through sheer energy; he’s a composer, essayist and novelist as well as a wonderful pianist. So it’s not surprising he turned the lockdown to his advantage. “It gave me a reason to get up and get to work in the morning, which I did fanatically, with more intensity than I have ever done in my life,” he says. “It was self-preservation, my way of coping with the lockdown.”

Were the recording sessions themselves different in any way? “Well, it was difficult not being able to do the musicians’ hug at a recording session! The great thing about Henry Wood Hall [in south-east London] where we recorded is that we were all in separate rooms, the engineer in one room, the producer in another, and me in the hall itself.

"The keyboard was sanitised regularly, and I had to listen to the playbacks on specially sanitised earphones, rather than the usual method of standing next to the producer in the control room. It actually worked very well, and I think even added to the feeling of focus and concentration.”

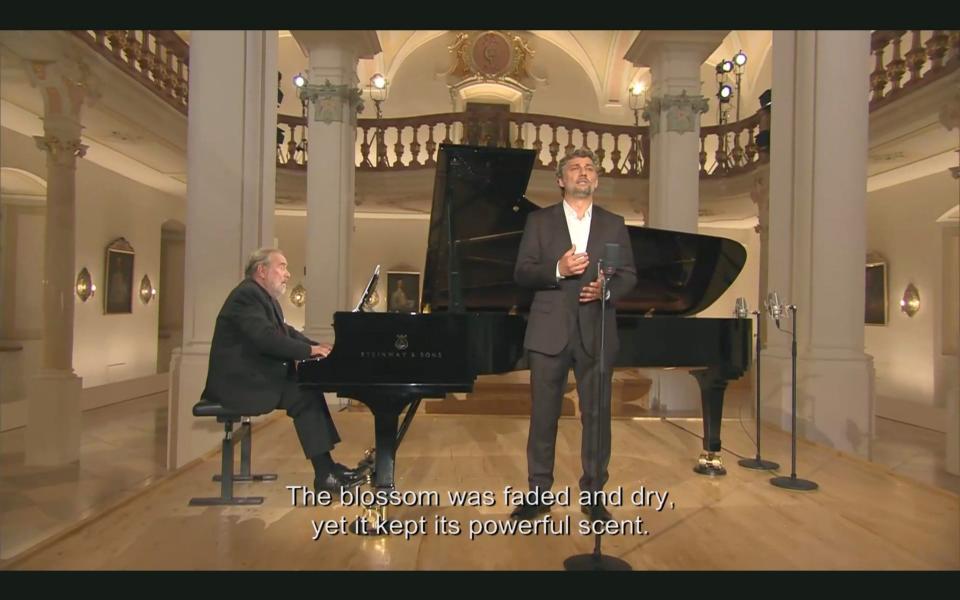

Other companies have also taken advantage of big-name artists’ empty diaries. Star German tenor Jonas Kaufmann was keen to make a recording of solo song in his own home just outside Munich, where he lives with his opera director wife Christiane Lutz and four children, and his record company Sony Classical was only too happy to oblige. But that raised a problem: his favourite accompanist, the pianist Helmut Deutsch, was in neighbouring Austria, and the border between the two countries was closed. “I had to make special arrangements with the border guards to let him through,” says Hauber. “And they called me when he arrived there, just so I could confirm it was really him.”

The stringent conditions have tested the industry’s technical creativity, and some engineers and producers have pulled off some remarkable feats. Freelance engineer and producer Simon Kiln has made recordings of Beethoven string quartets with an American quartet led by violinist James Ehnes, at a distance of 3,000 miles.

“James and I had planned to record all Beethoven’s late quartets at Wyastone Leys concert hall in Herefordshire, but the travel restrictions put the kibosh on that,” says Kiln. “So we did it remotely using a concert hall in Atlanta. I shipped some special gear over to them, and in early August we recorded them using an audio and video link from Atlanta to my studio.”

Some of these “remote” projects have been on a hugely ambitious scale. Decca Records worked with young star saxophonist Jess Gillam to record, mix and produce the debut performance of her Virtual Scratch Orchestra, a project she created to bring musicians together virtually, as they couldn’t play together in person. Musicians from anywhere in the world were invited to take part in Gillam’s arrangement of David Bowie’s Where Are We Now? and it was a runaway success; 1,000 participants from 26 countries contributed recordings of themselves, and Gillam performed along with them at the broadcast premiere on April 17.

But perhaps the biggest and most complex recording project of the entire lockdown was masterminded by producer Mike Hatch. He was invited by Opera North to film a brand-new community opera called Song of our Heartland, after its stage premiere was cancelled.

“We had to split the audio recording into its constituent parts because the combined orchestra, chorus and soloists were too big for any venue, when people were socially distanced,” says Hatch. “We recorded the orchestra in Leeds Town Hall, which is big but even so we had to take out all the seats to make it big enough. The chorus we split into groups, one of trebles and contraltos, another of tenors and basses, and we recorded each on a different day in a big warehouse space. Then we had another separate session for all the solo parts.”

This has left Hatch with a vastly difficult task of mixing and producing, ahead of the opera’s broadcast on Opera North’s website in the near future. “I’m working in 180 tracks, which is easily the most complex thing I’ve ever done.”

Where there’s a will there’s a way, has clearly been the industry’s watchword. But what of the future? Here industry leaders are more circumspect. Dominic Fyfe, label director of Decca Classics, says the lockdown has accelerated the trend towards streaming. “Lockdown has also brought new ways of listening and I think they’re here to stay. As for the future, I think this period has restored some of the aesthetic and economic value of recordings, but on the other hand we really need a thriving live music scene to return.”

Per Hauber agrees. “I think we’ll see the bad effects of the pandemic later, because concerts build audiences for CDs and downloads, and they have not been happening for months. Also, without concert-giving, record companies lose touch with emerging stars. How can we promote new talent if we don’t even know who they are?”

The industry has done well during the lockdown, but whether there’ll be “Jam tomorrow” remains to be seen.

Read more:

Our orchestras' only hope: how technology can fuse our splintered musicians together again

From the West End to the gig economy: how Britain's top musicians are struggling to survive