What I Couldn't Say Out Loud

“I ain’t never told nobody this before,” the guy in the back row said, his voice low, steady, emotionless. “But I killed my little brother.”

We took it in silently, the five of us on the dais and the sixty or so people in the room. Nobody knew how to react, because it was a lot, and also because he said it in the Q&A portion of a panel discussion about social media and type 1 diabetes. But he seemed to need to be unburdened, and nobody else was going to say anything, so he went on. He and his brother had both been diagnosed with type 1 in childhood, before either of them could remember, as many people are. It was the thing they had in common; the two were the only people they knew with the disease. Not that they ever discussed it. “It was hard to talk about, so we didn’t,” he said. “Neither of us wanted to ask the other one for help.” They both negotiated the confounding and complicated condition alone, this Tennessee man whom I guessed to be in his early sixties and the baby brother who didn’t make it that far. Side by side, or maybe with their backs to each other, they both lived with it. Until one of them didn’t.

What really surprised me about the guy’s story was how much of it made sense. I was diagnosed with type 1 in my forties, which happens less often, though still to a significant number of people. I dragged myself to an endocrinologist on the first business Monday of 2016, after a holiday season I had spent sick. I’d lost weight—a welcome development, then an alarming one. I was urinating a thousand times a day; I was thirsty constantly; I was ragged. The doctor ran the tests, put me on insulin that very day, had me inject myself right there in front of him. And just before I left his office, he looked me in the eye and said, “Get yourself a community of other adult type 1’s. Go on Meetup.com, find a happy hour, go and talk to people. You’re going to need it.”

He was right, and I knew it, which is why it was a little startling when I said, “That’s okay.” I’d just been diagnosed with a chronic disease that would fundamentally alter the way I lived my daily life; that part I could cope with. But admitting to another human being that I’d need to adjust? Asking for help? Unthinkable.

Type 1 diabetes is a disease you can manage, but you’re always on the clock. You assume the role of the pancreas that your immune system has shut down, so you alone are in charge of regulating your blood-sugar level. Before you eat a meal, you do a quick estimation of the carbohydrate content of the food and give yourself the appropriate amount of insulin to cover it. Each day involves a full workbook of fourth-grade math. It’s like driving on a winding road, checking constantly to make sure your speed never deviates by more than a couple miles per hour. It’s a lot.

But one thing it isn’t is a weakness. It’s a condition that strikes both young and old, both active and sedentary. There’s no moral dimension to it. It just is.

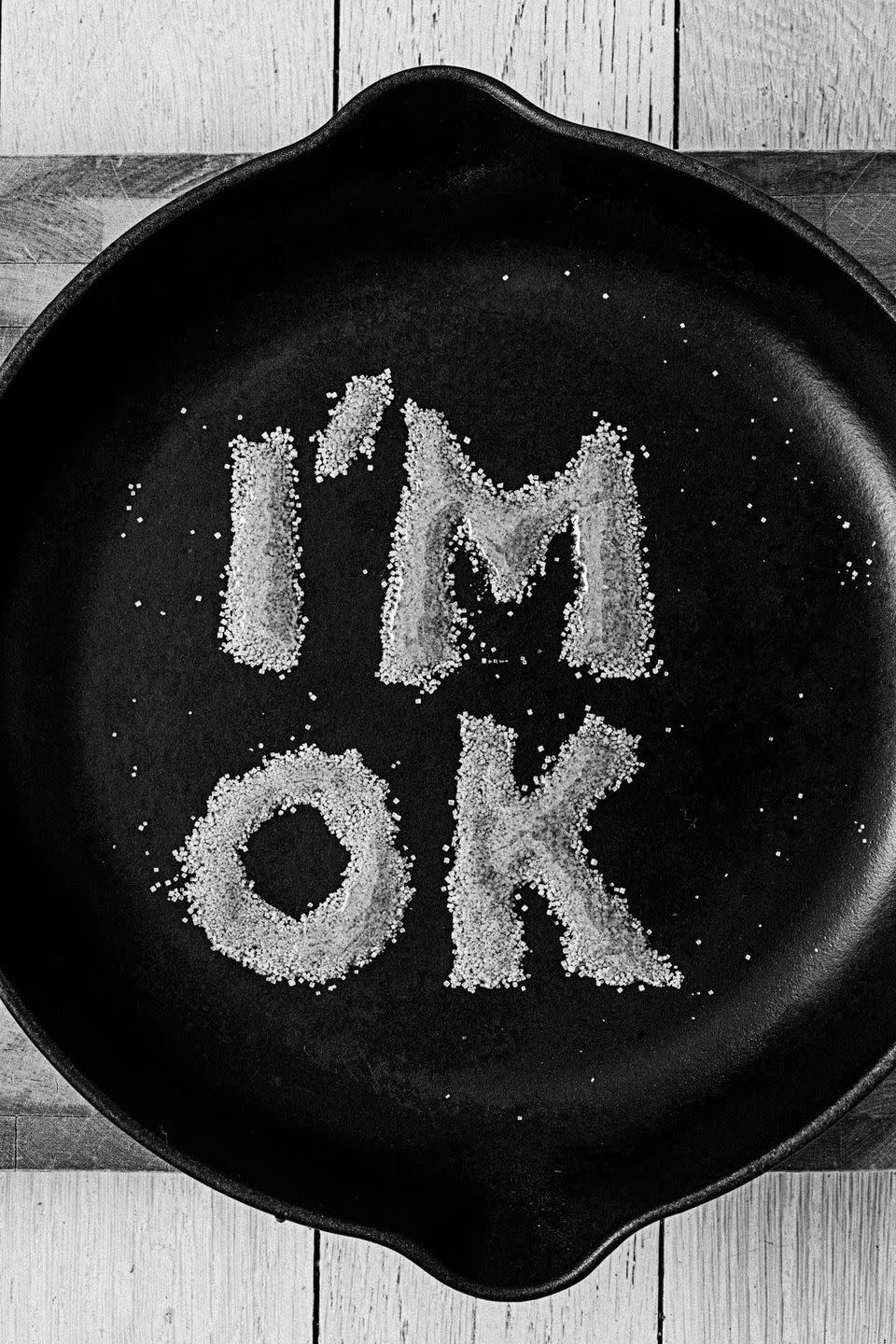

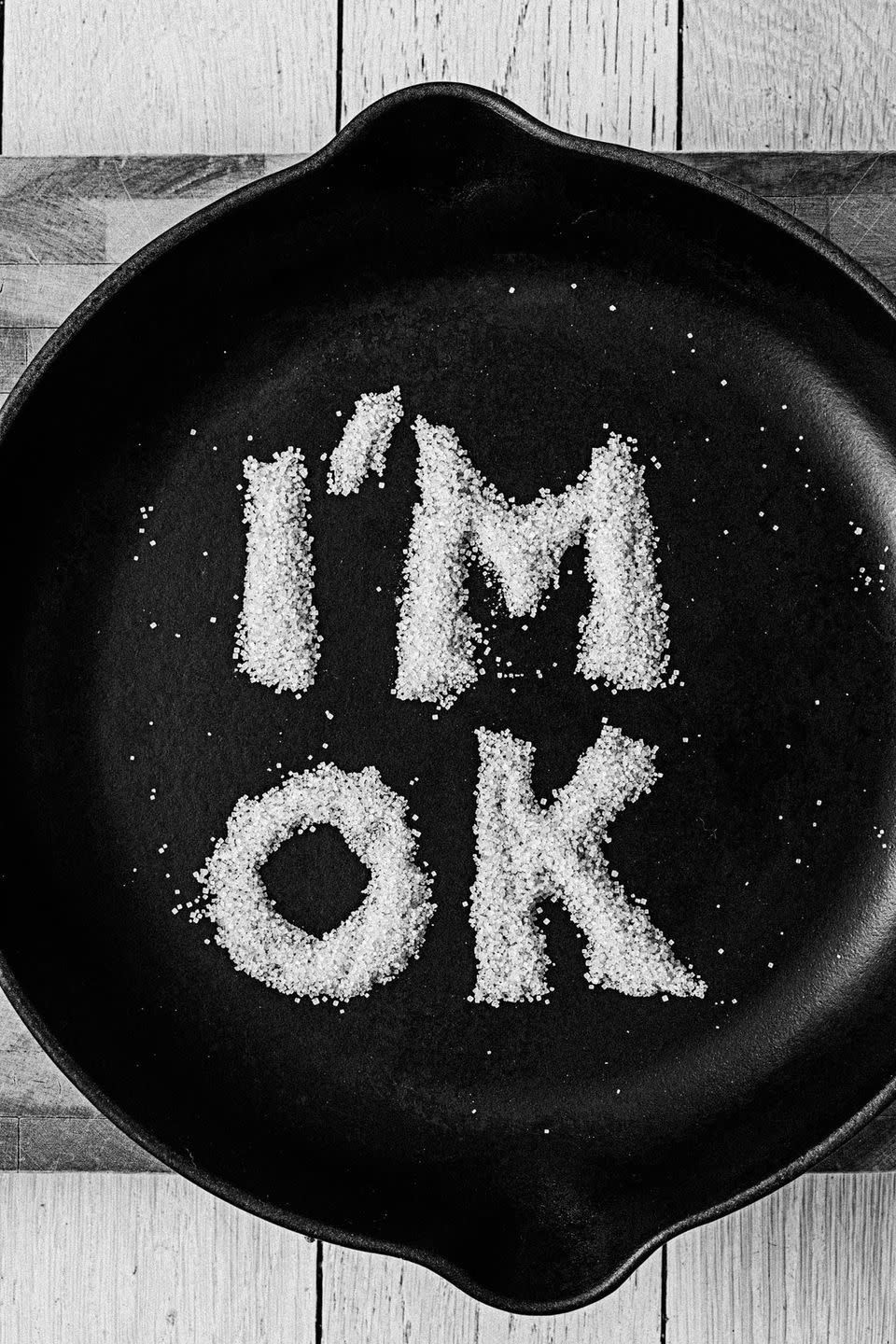

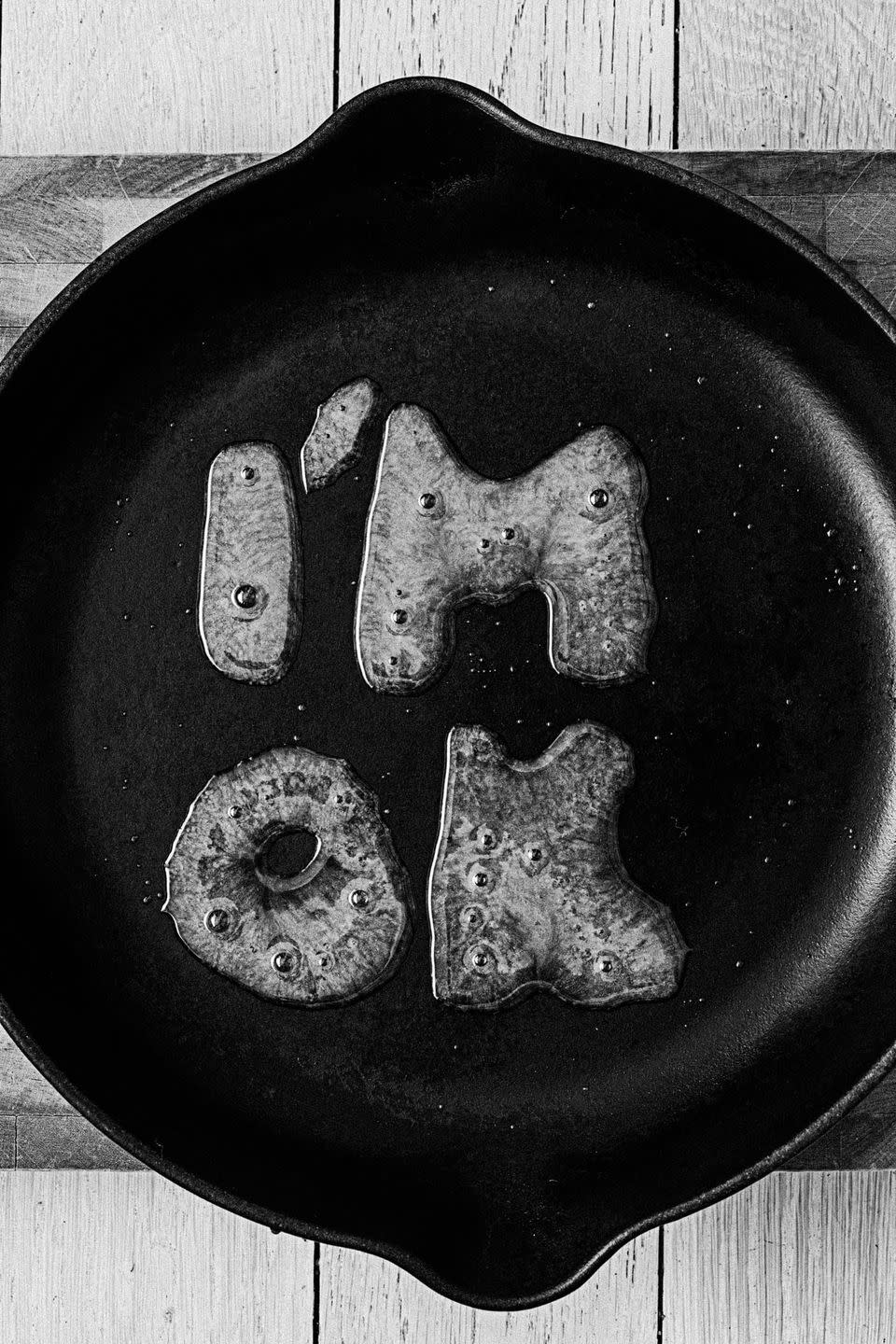

In the weeks after my diagnosis, I told everyone I knew about it. Part of it was relief that I finally knew what was wrong with me; part of it was having a story to tell over cocktails. But when my friends or family asked how I was adjusting to it, whether I was okay with the new normal, whether any of it scared me as much as it clearly did, I would answer quickly, reflexively: “I’m fine. It’s great. It’s easy.” It wasn’t. When I look back on that time in my life, I see myself struggling to get to sleep, fretting over every bite, testing my blood every quarter mile of every morning jog. A life lived in a full-blown panic attack, which I chose to manage alone. On a visit home, my mother noticed my shaking hands over dinner and addressed it with an elegantly indirect comment: “You know, when they say men are supposed to be strong, I think they mean in terms of opening difficult jars.” As clear an opening as I was ever going to get. I still didn’t take it.

If a guy like me—who’s published no fewer than three articles about how sad I was when my dog died—couldn’t ask for help with a thing as important and morally neutral as my basic health, what hope does everyone else have with the trickier stuff? With mental illness, depression, anxiety, just plain sadness? If I can’t handle going to a happy hour for adults with a chronic illness, how can I blame someone else for not considering therapy?

Somewhere within many of us is the desire to be the guy who has the answers, who never needs help. I pretended to be that guy when in reality I was a man with questions like “Will a long run kill me?” and “How do I eat now?” We’re all still struggling to fit into the suits we inherited from our fathers, never stopping to wonder how well those jackets fit them. We’re all still comparing ourselves to the men in old westerns, never asking whether silence really, empirically does mean strength, or whether John Wayne just wasn’t all that comfortable with dialogue.

If I eventually got over it, it’s only because I was impatient to start getting healthy again. I went to a meetup, met a few people in the same boat, asked some questions of people who’d dealt with it longer, answered a few for people who were diagnosed more recently than I was. I made some friends, got myself into a running group for other type 1’s, and over time felt my overall stress level diminish. I met a guy named Craig Stubing, who hosts a podcast called Beta Cell on which he interviews other type 1’s about their lives and habits and coping strategies. It’s a good listen, exactly the kind of thing a newly diagnosed diabetic needs to hear.

And for the record, while type 1 affects men and women in equal numbers, about 80 percent of the listeners who interact with Beta Cell’s social media are female. Stubing says, “I think type 1 can feel like a weakness, so men tend not to show it, talk about it, or interact with the community, because they don’t want to seem weak.” The one exception for men, not surprisingly, revolves around sports. “The men who do talk and post about it often use type 1 to show what they’ve overcome, to make themselves seem even manlier.” I look at my own Instagram, and the only times I’ve posted about my illness were after long runs when I managed to keep my glucose level stable. When I’d beaten it. When I’d won. Those times when I was less than Instagram perfect, when I might have needed some help, when I might have come off as vulnerable, I kept offline.

So here I am, forty-eight years old, dealing with a new health condition and realizing the degree to which a much worse one—this hideous thing we call toxic masculinity—has me by the throat. Enough. I can’t handle type 1 on my own. I need help. By the rules of the culture by which I was conditioned, saying that out loud makes me less of a man.

My God, what a relief.

The guy in the back row kept telling his story. Turns out his little brother had been trying to correct a stubborn high blood-sugar level and in so doing gave himself just a little too much insulin. He passed out from hypoglycemia behind the wheel of his car, hit a tree, bled to death. The guy in the back row has blamed himself ever since. He wishes he had said something to him, though he doesn’t know what. His little brother is dead because of a freak accident that had nothing to do with him, and now he is dying from misplaced guilt. An honest talk wouldn’t have saved his little brother’s life, but it could still save his.

I wanted to get to him after the forum was over, just to give him my info, see if he needed to get any more of it off his chest, try to plant the seed of the idea that his brother’s death was not his fault. But he was nowhere to be found. He must have split the second the forum ended. Before he even had a chance to talk.

It was like he willed himself to disappear.

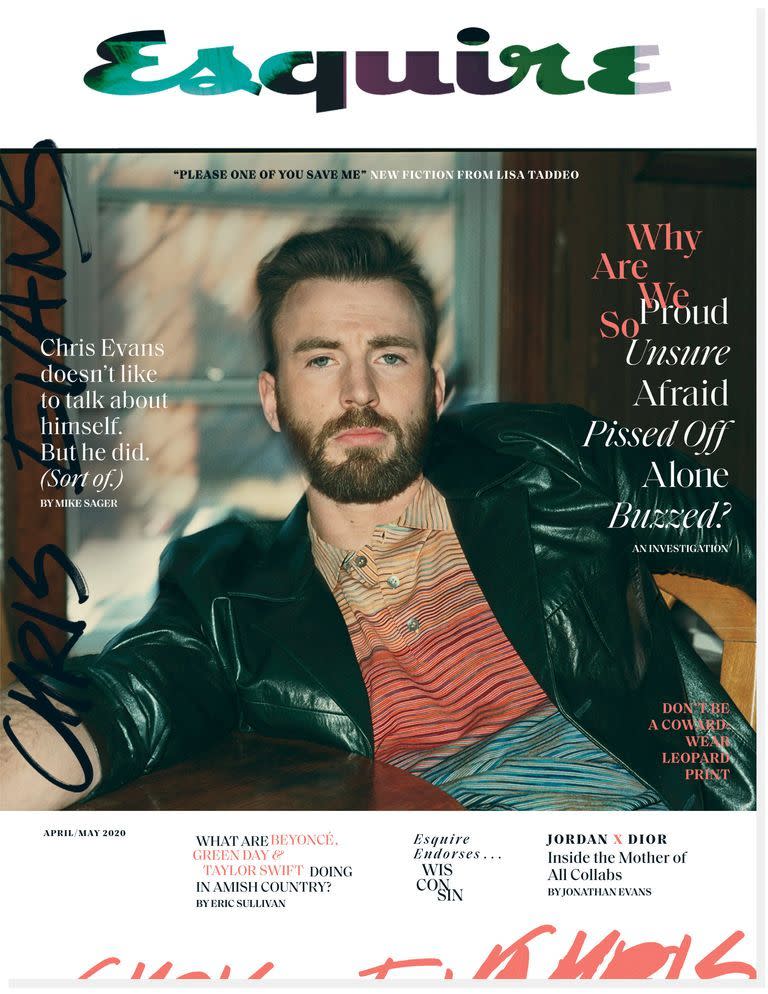

This article appears in the April/May issue of Esquire

Subscribe

You Might Also Like